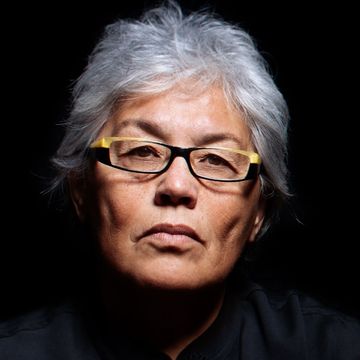

Through her works, Yamashita paints a picture of America in perhaps the only way it can be accurately portrayed; not as a monolith, not as a manifested destiny, and not as a melting pot, but as a mosaic whose tiles don’t quite line up,” literarian Josh Cook wrote of Karen Tei Yamashita in a dedication to the author on Literary Hub. “A mosaic with gaps, contradictions, and clashes, that doesn’t completely cohere into a single image.”

This mosaic theme is evident in the structure of Yamashita’s epic novel I Hotel, the California Book Club’s March 2022 selection. The book fits together many different stories of Asian American activism and protest in the 1960s and 1970s in the Bay Area. When it was published, in 2010, Yamashita’s eclectic and radical storytelling inspired both praise and criticism. On balance, the novel was received as masterful and innovative, but some critics, perhaps hoping for a more traditional novel, were more mixed, calling it slow and disjointed. It was a finalist for the National Book Award and received the 2010 California Book Award in the fiction category, as well as an American Book Award, an Asian/Pacific American Librarians Association Award, and an Association for Asian American Studies Book Award.

Stylistically unique, I Hotel combines traditional narrative with plays, poetry, full-page cartoons, and songs. In the Chicago Tribune, author Alan Cheuse described the novel as “encyclopedic” and “kaleidoscopic”: “It wants to inform and dazzle us on the confusions and conclusions on the question of culture and assimilation. And it often does.”

Back in 2010, the novel was noted by critics as a remarkable contribution to California historical literature, as one of the few fiction books on Asian American activism in the 1960s and ’70s. Yamashita spent a decade researching I Hotel, leading to what critic and editor Oscar Villalon called “an important history lesson clothed in sometimes lovely fiction.” Indeed, Yamashita’s novel is most significant in the radical-leftist story it tells, one that, as Villalon pointed out, is often excluded from the history books of a state known for its revolutionary 1960s.

However, upon I Hotel’s first publication, critics paid surprisingly less attention to Yamashita’s distinct manipulation of the text than they did to the characters that these manipulations serve, made more vibrant by the reworking of their story lines into each unique form. Critics disagreed on the extent to which Yamashita created whole characters in the lives of some of her protagonists, like the young revolutionary students. Cheuse, for instance, was critical of the characters’ tendencies toward “tedious sequences on the intricacies of Marxism-Leninism,” arguing that they slow the plot of the book and divest the reader from the lives of the characters. (The authors whose forms Cheuse offered as alternatives to Yamashita’s—John Steinbeck and early James Joyce—are known for their own canonical novels that use more-conventional structures.) But more recently, in the Nation, Lucas Iberico Lozada wrote, “Yamashita’s characters are not wooden stand-ins meant simply to hit their world-historical marks; they are bristling with life, constantly meeting, talking, striking, cooking, and falling in and out of love, of college, of prison.”

In 2019, in a testament to the novel’s enduring significance, Coffee House Press—which, in a literary relationship spanning three decades, has published all of Yamashita’s books—released a 10th-anniversary edition of I Hotel, with an introduction by the playwright and multimedia artist Jessica Hagedorn. She described the book as “a meta meta metaphor, part fiction and part fact, an immersive theatrical experience, a space-jazz-rock-funk opera, or all of the above.” The new edition was published a mere five months before the COVID pandemic caused a nationwide lockdown, precipitating a surge in reports of hate crimes. San Francisco reported a 567 percent increase in anti-Asian hate crimes in 2021, up from 8 cases in 2019 to 60 in 2021. “In these dark times of planetary crisis, sinister algorithms, and yammering despots, Karen Tei Yamashita’s mythic I Hotel seems more relevant than ever,” Hagedorn perceptively wrote. Devoting substantial time and attention to the diverse histories of California has perhaps never been more urgent.

Last year, Yamashita received the 2021 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, which was presented by Viet Thanh Nguyen, who called I Hotel her “masterpiece.” As Iberico Lozada put it, “the book’s republication serves as an emboldening reminder of fiction’s ability to both transmit and embody transformational ideas.” He wrote, “I Hotel is the extraordinary testimony of a revolutionary past, an archive whose flattened walls convey what is possible, both in politics and in art.”•

Yamashita will join the California Book Club on March 17 at 5 p.m. Pacific time to discuss I Hotel. To join the California Book Club, click here. Join us in the Alta Clubhouse to discuss the book. Register here for the event.

Jessica Blough is an associate editor at Alta Journal. She is a graduate of Tufts University and former editor in chief of the Tufts Daily.