Despite attracting considerable publicity the English Defence League (EDL) remains under-researched and poorly understood, according to a study by YouGov and the Extremis Project. Little is known about wider public attitudes toward the movement that was founded in 2009, or potential sympathy for its values and/or provocative demonstrations. This contrasts sharply with a large body of research on other far right groups in Britain, like the British National Party (BNP).

The absence of reliable research on the EDL is particularly striking given the movement’s intention of increasing its involvement in elections, for example by contesting an elected police commissioner role in Bedford, on November 15 2012.

To probe the issue, and build on earlier insights by the think-tank Demos, the Extremis Project worked with YouGov to undertake a large-scale survey of a nationally representative sample of 1,682 British adults (a description of our methodology and the full results are below). The aim was to shed light on what the public think about the English Defence League, and to explore which groups in society are most receptive to the movement’s anti-Islam and anti-Muslim message.

Public attitudes toward the EDL

Unlike elsewhere in Europe, the far right in Britain has long been treated as a political pariah. Since 2001, for example, and despite a favourable climate that has included record levels of public concern over immigration, the far right in Britain – namely the BNP – persistently failed to convince large numbers of voters that it was a credible and legitimate alternative. But to what extent do the British public similarly view the EDL as a toxic insurgent?

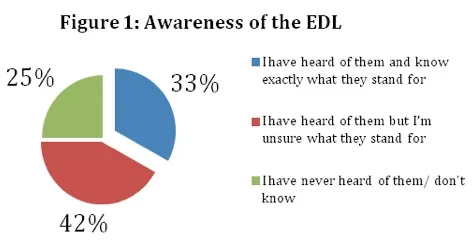

Before answering this question, we first wanted to explore the extent to which people are actually aware of the movement, given that it was only founded in 2009 and has largely been excluded from mainstream political debate and media. Our findings mirror this fact, suggesting the EDL has struggled to communicate its ideas to the wider public and is far from a ‘household name’.

In the survey, those who said they ‘have heard of them but are unsure what they stand for’ clearly outnumber those who said they ‘have heard of them and know exactly what they stand for’. In fact, more than two-fifths of respondents – or 42% of our sample – said that although they had heard of the English Defence League, they were unsure what the movement stands for. In contrast, only one-third had heard of the movement and were aware of its platform, while one-quarter had ‘never heard’ of the EDL.

It is also worth noting a significant gender gap in levels of awareness about the EDL: while 40% of men had heard of the group and claimed to know what it stands for, only 26% of women had a similar level of awareness. Meanwhile, the percentage of women who had never heard of the movement (26%) was over two-fold higher than the equivalent figure among men (10%). More generally, respondents aged between 18-24 years old, and those who are based in Scotland, London and northern England were the most likely to have heard of the EDL and know what it stands for.

Who is receptive?

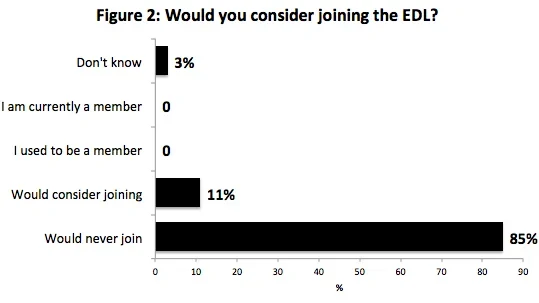

To explore whether there is public sympathy for the movement, we asked respondents a series of further questions, but only to those who had heard of the EDL and know what they stand for –i.e. those people in our survey who are aware of the movement and its ideas. It makes little sense to ask questions about the EDL to people who have never heard of the movement. This reduced our overall number of respondents from over 1,600 to 548.

Among these 'EDL-aware' respondents, how likely would they be -if at all- to consider joining the organization? This question sheds some light on the extent of possible sympathy for the group. Similar to the reaction of the British public to other far right groups, however, we find that a clear and overwhelming majority perceive the EDL as a pariah: almost nine out of every ten respondent – or 85% of our EDL aware group – said they would 'never consider' joining. Only around one out of every ten respondent –or 11%- said they would consider joining, while 3% said they did not know whether or not they would consider joining.

To what extent do these responses vary across different social groups? Past research on public support for the far right suggests that those who are most receptive to the appeals of the far right tend to be skilled manual workers, semi- and unskilled workers, and citizens dependent on the welfare state for their income (often referred to as the ‘C2DE’ social grades). In contrast, citizens from the upper, middle and lower middle classes have generally been shown to be less likely to endorse the far right.

Consistent with the picture above, our results suggest that those within the C2DE categories are three times as likely as those from the ABC1 categories to say they would consider joining the EDL: whereas 19% of respondents from the more economically insecure and less flexible lower social classes said they would consider joining, only 6% of those in the more affluent and flexible social classes would think about enrolling. However, in both groups those who would consider joining the English Defence League are in a clear minority.

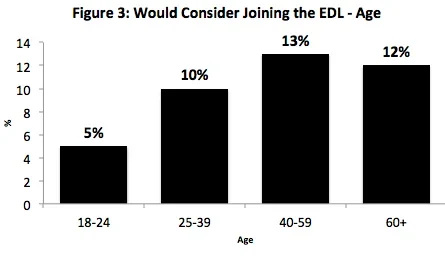

Also consistent with the wider evidence is our finding that men are the most receptive to the EDL. In fact, in our survey men are twice as likely as women to consider joining. Turning to age, and perhaps counter-intuitively, we find that it is older respondents –i.e. those aged 40 years and above- who are slightly more likely than younger respondents to consider joining.

Attitudes toward the values and strategy of the EDL

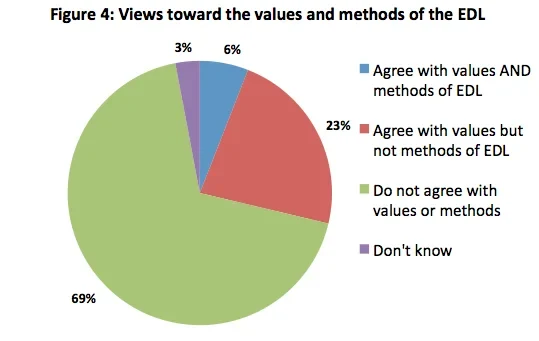

To further explore these attitudes, we asked respondents whether they agree or disagree with the values and/or methods of the English Defence League. Previous academic studies have pointed to significant amounts of latent public sympathy in Britain for some of the core ideas advocated by the far right, such as reducing immigration, adopting tough measures toward minority communities and more restrictive policies on law and order. But at the same time, it appears unlikely that large numbers of voters would endorse the EDL’s provocative strategy of ‘march-and-grow’, which is often associated with violence - whether stemming from the rank and file, or anti-fascist opponents.

As above, we restrict our analysis only to those citizens are aware of the EDL and its platform. Within this sample –and as expected- we find that a clear majority of respondents distance themselves from both the values and the methods of the English Defence League: more than two thirds – 69% – said they ‘do not agree with either the values or the methods’ of the group.

At the same time, however, we do find a significant level of sympathy for the values of the EDL, if not its provocative street-based strategy. In fact, almost one-quarter of those who are aware of the movement -or 23%- ‘agree with their values, but not their methods’. While a large majority disagree with both the ideas and tactics of the EDL, this nonetheless provides some tentative evidence that in British society there is a significant degree of sympathy for its anti-Islam and anti-Muslim message.

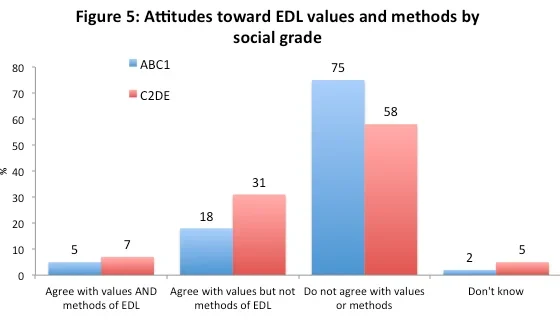

Mirroring the findings above, we find again that it is skilled, semi- and unskilled workers, and those on state benefits, who are the most likely to endorse the values of the EDL, if not its methods. Among those who are already aware of the movement, 31% of respondents from the working classes and those on benefits agree with the values of the EDL but not its methods, compared to 18% of respondents from the upper and middle-classes. Meanwhile, whereas 75% of respondents from the upper and middle-classes do not agree with the movement’s ideas or methods, among those in the C2, D and E categories the equivalent figure is significantly lower, at 58%. It is also worth noting the regional pattern: agreement with the values of the EDL (but not its methods) is highest in northern England (27%) and the Midlands (27%) regions, but lowest in London (20%) and Scotland (9%).

The racism question

Aside from exploring public views toward the EDL's values and strategy, we also wanted to ask people whether they consider the movement to be racist. Since their emergence, EDL leaders have repeatedly sought to distance their movement from accusations of racism, and have claimed they are interested only in the perceived 'threat' from Islam and Muslim communities.

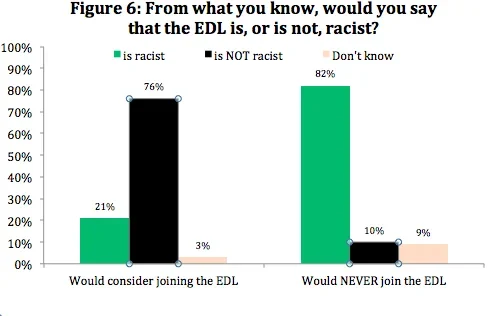

The survey, however, suggests that large sections of the electorate remain deeply unconvinced, and perceive the English Defence League to be racist. Almost three-quarters of the respondents who said they were aware of the EDL – or 74% – took the view that it is a ‘racist organization’. Less than one-fifth – or 17% – took the opposing view that the group is not racist, while 9% said they do not know whether or not the EDL is racist. As we might expect, a large majority of those who said they would consider joining the EDL – or 76% – reject the notion that the group is racist. Interestingly, however, we also find a significant minority – 21% – who would both consider joining the EDL and accept that the organization is a racist movement. While this group is clearly a minority, it does suggest that – for some disgruntled citizens – accusations of racism are not necessarily a deterrent to joining the movement.

Conclusions

The above survey offers unique and unparalleled insight into public attitudes toward the most recent member of the far right political family. The results point toward five conclusions.

The first is that only a minority of the population are aware of the English Defence League, and what it stands for. This suggests that while the movement has failed to mobilise a mass base of supporters, and has more recently suffered from infighting, it has more broadly failed to connect with most people. The second is that among those citizens who are aware of the EDL and its platform, a large majority do not view the movement as a credible and legitimate alternative. Rather, the results suggest that among those citizens who are aware of the EDL and what it stands for, almost nine out of every ten would never consider joining. In summary, and unless the movement or the wider political climate take a sharp turn, it looks distinctly unlikely that the EDL will extend its appeal more widely across British society.

The third key message is that – while they form a clear minority – the citizens who are most receptive to the English Defence League exhibit a similar social profile as supporters of the far right more generally: they tend to be men; come from the working classes; and are spread quite widely across different age groups, but have a slight bias toward the middle-aged. Contrary to common assumptions, we find little evidence that the EDL is only attractive to young people.

Fourth, while a large majority reject both the values and the methods of the English Defence League, there is a significant level of sympathy for the movement's values but not its methods. This suggests that while the EDL's provocative tactics are clearly a turn-off, the movement's anti-Islam and anti-Muslim platform has resonated among a significant number of voters. Addressing these public anxieties over perceived threats from specific minority communities – which lie outside of 'mainstream' debates over immigration – is clearly one challenge facing the mainstream political parties.

Finally, the results also suggest that attempts to counter racism will only go so far in terms of limiting the appeal of the far right. This is reflected in the finding that while a significant number of respondents consider the EDL to be racist, they would nonetheless still consider joining the group. This indicates that while the English Defence League is opposed by large sections of the population, it may have rallied a small hardcore of followers who are simply not turned off – or indeed are attracted by – racist beliefs and discourse.

Methodology of the research

Our survey was conducted using an online interview administered to members of the YouGov GB panel of over 350,000 individuals, who have agreed to take part in surveys. An email was sent to panellists selected at random from the base sample according to the sample definition, inviting them to take part in the survey and providing a link to the survey. The responding sample is weighted to the profile of the sample definition to provide a representative reporting sample. In other words, the figures that we report above are weighted and representative of all GB adults (aged 18+). The profile is normally derived from census data or, if not available from the census, from industry accepted data. Our total sample size was 1,682 adults, and the survey was carried out online, between 10-11th September 2012.