Four in Balance Monitor 2011 - downloads.kennisn... - Kennisnet

Four in Balance Monitor 2011 - downloads.kennisn... - Kennisnet

Four in Balance Monitor 2011 - downloads.kennisn... - Kennisnet

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

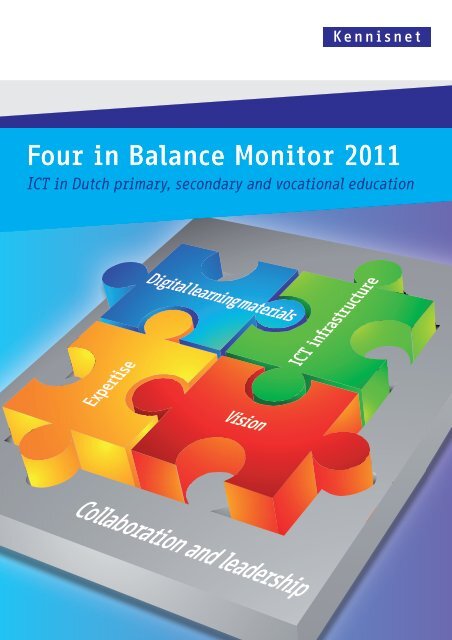

<strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> <strong>2011</strong><br />

ICT <strong>in</strong> Dutch primary, secondary and vocational education<br />

Expertise<br />

Digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials<br />

Vision<br />

Collaboration and leadership<br />

ICT <strong>in</strong>frastructure

<strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> <strong>2011</strong><br />

ICT <strong>in</strong> Dutch primary, secondary and vocational education

4<br />

Contents<br />

Ma<strong>in</strong> topics 6<br />

1 What is <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong>? 9<br />

1.1 The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model 9<br />

1.2 What do we mean by “balance”? 10<br />

1.3 The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> 13<br />

2 Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICT 15<br />

2.1 <strong>Kennisnet</strong>’s research program 15<br />

2.2 Classify<strong>in</strong>g ICT applications by pedagogical vision 17<br />

2.3 ICT and <strong>in</strong>struction 19<br />

2.4 Structured practice 21<br />

2.5 Inquiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g 25<br />

2.6 Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn 29<br />

2.7 Summary 31<br />

3 ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g 33<br />

3.1 Teachers at school 33<br />

3.2 Teachers at home 38<br />

3.3 Pupils at home 39<br />

3.4 Summary 43<br />

4 Vision 44<br />

4.1 Views on learn<strong>in</strong>g 44<br />

4.2 Compar<strong>in</strong>g school managers and teachers 46<br />

4.3 Innovation 47<br />

4.4 Summary 48

5 Expertise 49<br />

5.1 Familiarity 49<br />

5.2 Pedagogical ICT skills 50<br />

5.3 Summary 52<br />

6 Digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials 53<br />

6.1 Computer programs 53<br />

6.2 Percentage of digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials 55<br />

6.3 Source 56<br />

6.4 Summary 57<br />

7 ICT <strong>in</strong>frastructure 58<br />

7.1 Computers 59<br />

7.2 Interactive whiteboards 62<br />

7.3 Connectivity 64<br />

7.4 Summary 65<br />

8 Collaboration and leadership 66<br />

8.1 Collaboration 66<br />

8.2 Leadership 68<br />

8.3 The future 72<br />

8.4 Summary 73<br />

9 From ICT use to more effective teach<strong>in</strong>g 74<br />

9.1 Adapt support to aims 74<br />

9.2 Use leadership to <strong>in</strong>volve followers 76<br />

9.3 Formalize professional use 76<br />

9.4 L<strong>in</strong>k teacher, pupil, and subject matter<br />

<strong>in</strong> a digital learn<strong>in</strong>g environment 77<br />

9.5 Know what works 78<br />

10 Bibliography 80<br />

5

6<br />

Ma<strong>in</strong> topics<br />

The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> is published annually by <strong>Kennisnet</strong> and<br />

concerns the use and benefits of ICT <strong>in</strong> Dutch education. The <strong>Monitor</strong><br />

is based on <strong>in</strong>dependent research and looks at primary, secondary<br />

and vocational education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Below, we summarize the<br />

ma<strong>in</strong> topics covered <strong>in</strong> the <strong>2011</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong>.<br />

Benefits<br />

• ICT can make teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g more efficient, more effective, and<br />

more <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

• ICT use has become commonplace <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> recent years.<br />

Nevertheless, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g ICT use does not necessarily lead to better<br />

results. The more powerful ICT becomes and the more options it offers<br />

for improv<strong>in</strong>g the quality of education, the more crucial the teacher’s<br />

role becomes.<br />

• The benefits of ICT depend largely on the presence of a teacher who is<br />

able to l<strong>in</strong>k the subject matter, the ICT application, and the pupil.<br />

Use by teachers<br />

• Three quarters of teachers use computers dur<strong>in</strong>g lessons. This number<br />

has <strong>in</strong>creased by 2 to 3% <strong>in</strong> recent years.<br />

• Teachers spend an average of 8 hours a week us<strong>in</strong>g computers <strong>in</strong> their<br />

lessons, and that figure is expected to <strong>in</strong>crease with<strong>in</strong> three years by<br />

approximately 40%, to 11 hours a week. In addition, they spend another<br />

7 hours a week on average do<strong>in</strong>g school-related work on their home<br />

computer.<br />

• The ICT applications used most often <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g are the Internet,<br />

practice programs, word process<strong>in</strong>g software and electronic learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

environments. Games and Web 2.0 are used the least.<br />

Use by pupils<br />

• Teachers believe that the number of hours that pupils can spend<br />

work<strong>in</strong>g at a computer at school is limited to between 1.5 and 3 hours<br />

a day. Teachers believe that pupils can spend a further 7 to 12 hours a<br />

week on computer-based learn<strong>in</strong>g activities outside of school.<br />

• It is wrongly assumed that youngsters are so skilful with computers

that schools do not need to teach them how to search for and select<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation on the Internet. Many pupils have a difficult time us<strong>in</strong>g ICT<br />

responsibly, critically, and creatively as a learn<strong>in</strong>g tool.<br />

• The majority of pupils <strong>in</strong> vocational education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g take their<br />

own laptops with them to school. This happens much less <strong>in</strong> secondary<br />

education, and scarcely at all <strong>in</strong> primary school.<br />

Vision<br />

• Knowledge transfer is the most common teach<strong>in</strong>g method today, and will<br />

rema<strong>in</strong> so <strong>in</strong> the future. Teachers and school managers expect that ICT<br />

will be used most frequently for purposes of knowledge transfer.<br />

• Knowledge construction will become more common <strong>in</strong> education <strong>in</strong> the<br />

future. Teachers and school managers believe that ICT will support this<br />

trend.<br />

• Teachers assume that they will cont<strong>in</strong>ue teach<strong>in</strong>g largely without the<br />

support of ICT. School managers th<strong>in</strong>k otherwise, however; they expect<br />

that with<strong>in</strong> three years’ time, teachers will be us<strong>in</strong>g ICT <strong>in</strong> most of their<br />

lessons.<br />

Expertise<br />

• Two thirds of teachers feel that they are sufficiently or more than<br />

sufficiently familiar with the various options that ICT can offer them <strong>in</strong><br />

their teach<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

• School managers say that eight out of ten teachers have satisfactory<br />

technical ICT skills; for example, they can use a word process<strong>in</strong>g<br />

program and the Internet.<br />

• School managers estimate that almost six out of ten teachers have<br />

mastered the pedagogical skills they need to use ICT <strong>in</strong> their teach<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials<br />

• Teachers ma<strong>in</strong>ly use standard office applications such as word<br />

process<strong>in</strong>g programs and e-mail. Slightly more than half of teachers also<br />

used software associated with a course/coursebook or a subject-specific<br />

program.<br />

• A fourth of all learn<strong>in</strong>g material is digital. Teachers expect that this<br />

share will <strong>in</strong>crease considerably <strong>in</strong> the years ahead.<br />

• Approximately a third of teachers occasionally develop their own digital<br />

MAIN ToPICS<br />

7

8<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g materials. That is 10% more than two years ago. In two years’<br />

time, more than half of teachers expect to be develop<strong>in</strong>g their own<br />

digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials.<br />

Infrastructure<br />

• The ratio of computers to pupils at school is the same as last year: one<br />

computer for every five pupils.<br />

• The adoption of <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboards has gone much faster than<br />

school managers had anticipated <strong>in</strong> previous surveys. Almost every<br />

school now has one or more <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboards. Expectations are<br />

that nearly every primary school classroom will be equipped with an<br />

<strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard before long.<br />

• Wireless Internet and optical fiber connections are becom<strong>in</strong>g standard<br />

at secondary schools and <strong>in</strong> the vocational education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

sector.<br />

Collaboration and leadership<br />

• Two thirds of teachers say that ICT use is a matter of personal<br />

preference, and that there are no shared (school-wide) goals.<br />

• Approximately eight out of ten schools have an ICT policy plan. About<br />

half of these schools are actually implement<strong>in</strong>g this plan.<br />

• At the moment, school managers are focus<strong>in</strong>g on purchas<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>frastructure facilities and digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials (material<br />

factors). In order to ensure that more teachers make better use of ICT,<br />

school managers would like to place put greater emphasis on teachers’<br />

professional development and on develop<strong>in</strong>g a pedagogical vision<br />

concern<strong>in</strong>g the use of ICT (human factors).<br />

From use to better performance<br />

• There are solid foundations for us<strong>in</strong>g ICT <strong>in</strong> every sector of education.<br />

Schools can get more out of ICT by:<br />

1. adapt<strong>in</strong>g support to aims;<br />

2. us<strong>in</strong>g leadership to get followers <strong>in</strong>volved;<br />

3. formaliz<strong>in</strong>g professional use;<br />

4. l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g teacher, pupil and subject matter <strong>in</strong> a digital learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

environment;<br />

5. know<strong>in</strong>g what works.

1<br />

What is <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong>?<br />

1 - WhAT IS FoUr IN BALANCE?<br />

1.1 The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model<br />

The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> is based on the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model. This<br />

model summarizes what research has taught us about how schools can use<br />

ICT successfully to improve the quality of education.<br />

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model, <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g ICT for educational<br />

purposes has a greater chance of success if four basic elements – vision,<br />

expertise, digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials and ICT <strong>in</strong>frastructure – are <strong>in</strong><br />

balance (Ict op School, 2004). These basic elements are complementary and<br />

mutually dependent.<br />

Below, we briefly expla<strong>in</strong> the four basic elements:<br />

• Vision: what the school believes good teach<strong>in</strong>g is and how the school<br />

<strong>in</strong>tends to achieve it. Vision consists of the school’s objectives, the role<br />

of teachers, pupils and management, the actual content to be taught,<br />

and the materials that the school uses.<br />

• Expertise: teachers’ knowledge and skills, which must be good enough<br />

to utilize ICT to achieve educational objectives. This refers not only to<br />

technical skills, but also to pedagogical knowledge and to knowledge<br />

of the subject matter – as well as to the ability to mean<strong>in</strong>gfully l<strong>in</strong>k all<br />

three.<br />

• Digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials: all digital educational content, whether<br />

formal or <strong>in</strong>formal. Formal learn<strong>in</strong>g materials are materials produced<br />

especially for educational purposes. Digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

computer programs.<br />

• ICT <strong>in</strong>frastructure: the availability and quality of computers, networks,<br />

and Internet connections. ICT <strong>in</strong>frastructure also <strong>in</strong>cludes electronic<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g environments and the ma<strong>in</strong>tenance and management of ICT<br />

facilities.<br />

The education sector’s task is to closely coord<strong>in</strong>ate these four basic<br />

elements when plann<strong>in</strong>g, facilitat<strong>in</strong>g and implement<strong>in</strong>g teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

processes. Teachers play a crucial role <strong>in</strong> this, but there is also a need<br />

9

10<br />

Leadership<br />

for leadership to guide the process and to create the right conditions for<br />

collaboration with other professionals (see Figure 1.1).<br />

Vision Expertise<br />

Collaboration<br />

Digital learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

materials<br />

Pedagogical use of ICT for teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Improvement <strong>in</strong> quality of education<br />

Figure 1.1: The basic elements of the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model (Ten Brummelhuis, <strong>2011</strong>)<br />

ICT<br />

<strong>in</strong>frastructure<br />

1.2 What do we mean by “balance”?<br />

In this <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> we look at each of the basic elements of the<br />

<strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model separately, so that we understand the priorities that<br />

schools set for themselves and the basic conditions <strong>in</strong> which they <strong>in</strong>vest. That<br />

gives us an idea of how th<strong>in</strong>gs stand across the country. The questions we<br />

ask <strong>in</strong>clude: What <strong>in</strong>frastructure facilities do schools purchase? Do they have<br />

enough digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials at their disposal, or are there bottlenecks?<br />

how much effort do schools put <strong>in</strong>to develop<strong>in</strong>g a pedagogical vision<br />

regard<strong>in</strong>g the use of ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g?<br />

The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model is not only a useful conceptual framework for a<br />

national benchmark, it is also an implementation model for the susta<strong>in</strong>able<br />

use of ICT <strong>in</strong> education. <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> is not <strong>in</strong>tended to compel schools to<br />

use ICT. It is <strong>in</strong>tended to help the schools that wish to use ICT make choices<br />

that will improve the quality of teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g and achieve the related<br />

benefits.

1 - WhAT IS FoUr IN BALANCE?<br />

In many cases, schools fail to achieve the benefits that they thought they<br />

would atta<strong>in</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g ICT. For example, a project falters because the teachers<br />

are not equipped to use the technology, or because the <strong>in</strong>frastructure that<br />

the school has chosen does not match the pedagogical approach that teachers<br />

favor. The project then never goes beyond a one-time experiment (Van der<br />

Neut, 2010; Van Eck, 2009; 2010). one well-known example was described by<br />

Zucker <strong>in</strong> an article <strong>in</strong> Science. Zucker looked at the <strong>in</strong>vestment schools <strong>in</strong><br />

the United States had made <strong>in</strong> laptops (Zucker, 2009). Although the schools<br />

had spent a lot of money on the laptops and related equipment, teachers<br />

scarcely changed their lessons and failed to use many of the new options at<br />

their disposal. There was no impact on the way pupils thought or learned.<br />

Similar f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs have emerged <strong>in</strong> studies explor<strong>in</strong>g the impact of <strong>in</strong>teractive<br />

whiteboards (DiGregorio, 2010; Bannister, 2010).<br />

The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model allows schools to avoid such pitfalls by help<strong>in</strong>g<br />

them consider, <strong>in</strong> advance, how to organize teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g and what to<br />

<strong>in</strong>vest <strong>in</strong>. Thanks to research, we are com<strong>in</strong>g to learn more and more about<br />

how best to coord<strong>in</strong>ate the four basic elements. one important f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g<br />

is that the human factors (vision and expertise) must be considered first,<br />

and only then the material ones (learn<strong>in</strong>g materials and <strong>in</strong>frastructure). In<br />

previous publications, we referred to this particular coord<strong>in</strong>ation sequence<br />

as “education-driven <strong>in</strong>novation” (Law, 2008; De Koster, 2009). The opposite<br />

sequence, which starts with technology or digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials, is known<br />

as “technology-driven” or “material-driven” <strong>in</strong>novation (see Figure 1.2).<br />

Vision Expertise<br />

Education-driven<br />

Technology-driven<br />

Digital<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

materials<br />

ICT <strong>in</strong>frastructure<br />

Figure 1.2: Two coord<strong>in</strong>ation sequences: education-driven (start<strong>in</strong>g from the human factors)<br />

and technology-driven (start<strong>in</strong>g from the material factors). Education-driven coord<strong>in</strong>ation has<br />

a better chance of succeed<strong>in</strong>g<br />

11

12<br />

Coord<strong>in</strong>ation that puts technology before pedagogy has only a limited chance<br />

of success (Fullan, <strong>2011</strong>; Kozma, 2003; Ten Brummelhuis, 2008).<br />

Crucial human factors <strong>in</strong>clude the follow<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

• The ICT facilities match the teacher’s views on education<br />

If so, then the teacher will certa<strong>in</strong>ly not be unwill<strong>in</strong>g to use ICT <strong>in</strong> his<br />

or her lessons (oECD, 2010b; Van Gennip, 2008; Versluijs, <strong>2011</strong>). If an<br />

ICT application conflicts with the teacher’s pedagogical pr<strong>in</strong>ciples,<br />

however, he or she will prefer not to use ICT. Teachers will not easily<br />

give up their pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, because they derive much of their professional<br />

identity from them (Ertmer, 2005; 2009). We look more closely at this <strong>in</strong><br />

Section 4.3.<br />

• The teacher is familiar with ICT and is capable of us<strong>in</strong>g it<br />

If not, then his or her use will be <strong>in</strong>effective. This is <strong>in</strong> fact a key factor<br />

(Knezek, 2008; Van Buuren, 2010). once the teacher is familiar with the<br />

technology, he or she must <strong>in</strong>tegrate it <strong>in</strong>to the subject matter and his<br />

or her pedagogical approach. This type of knowledge is referred to as<br />

TPACK, that is: Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (Voogt,<br />

2010a).<br />

• The teacher is conv<strong>in</strong>ced of the added value of ICT<br />

If not, then he or she will tend to stick to a familiar rout<strong>in</strong>e (Tondeur,<br />

2008; Voogt, 2010a). It is important for teachers’ professional<br />

development to understand which ICT-related pedagogical strategies<br />

will lead to better pupil performance (Erstad, 2009; hattie, 2009;<br />

Timperly, 2007).<br />

• There is leadership<br />

A demonstration of leadership can get teachers <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>novation,<br />

motivate them, and allow them to develop a shared vision (Dexter, 2008;<br />

Vanderl<strong>in</strong>de, <strong>2011</strong>; Waslander, <strong>2011</strong>) – not only the trendsetters, but<br />

also (and more specifically) the more hesitant majority (Fullan, <strong>2011</strong>;<br />

Schut, 2010). We will look more closely at the issue of “leadership” <strong>in</strong><br />

Chapter 8.

1.3 The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong><br />

1 - WhAT IS FoUr IN BALANCE?<br />

Benchmark<br />

The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> provides figures on how Dutch schools<br />

<strong>in</strong>tegrate ICT <strong>in</strong>to teach<strong>in</strong>g and the results they achieve by do<strong>in</strong>g so. The<br />

data reveal trends and offer schools a benchmark for compar<strong>in</strong>g their<br />

own situation with those of other educational <strong>in</strong>stitutions (Chapters 3 to<br />

8). The <strong>Monitor</strong> covers the three sectors <strong>in</strong> which <strong>Kennisnet</strong> is <strong>in</strong>terested:<br />

primary education, secondary education, and vocational education and<br />

tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. When discuss<strong>in</strong>g research on primary education that does not<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude special education, we refer simply to primary education.<br />

In addition to survey<strong>in</strong>g the current state of affairs, the <strong>Monitor</strong> reviews<br />

what research has taught us about the benefits of ICT (Chapter 2). The <strong>Four</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> shows that we are gradually acquir<strong>in</strong>g more knowledge<br />

of the effects of ICT. At the same time, this publication also shows that<br />

there are still many questions concern<strong>in</strong>g the long-term benefits of ICT<br />

<strong>in</strong> education. By systematically generat<strong>in</strong>g new knowledge and provid<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the latest <strong>in</strong>formation about what does and does not work, we aim to<br />

help schools select the ICT applications that will improve their pupils’<br />

performance. Such <strong>in</strong>formation can also help developers, educational<br />

support staff, policymakers, and commercial parties meet the support<br />

needs of schools that utilize ICT.<br />

Sources<br />

What we know about the benefits of ICT is based on the results of<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent research. A considerable percentage of that research has been<br />

carried out on behalf of <strong>Kennisnet</strong> by various research <strong>in</strong>stitutions with<strong>in</strong><br />

the context of the “Mak<strong>in</strong>g Knowledge of Value” [Kennis van Waarde Maken]<br />

research program. This program also covers closely related research<br />

projects, for example “Learn<strong>in</strong>g with more effect” [Leren met meer effect],<br />

EXPo and EXMo (see also Chapter 2).<br />

To show how the current situation compares with previous years, we<br />

present comparative data collected <strong>in</strong> previous studies. We also use data<br />

taken from other Dutch and <strong>in</strong>ternational studies to help us understand<br />

13

the basic elements of the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model. Information on these<br />

sources can be found <strong>in</strong> Chapter 10. Virtually all of the sources can also be<br />

consulted via the <strong>Kennisnet</strong> website (onderzoek.<strong>kennisn</strong>et.nl).<br />

What’s new <strong>in</strong> <strong>2011</strong>?<br />

The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>es all the knowledge we have acquired<br />

so far about the use of ICT <strong>in</strong> education. While the <strong>2011</strong> <strong>Monitor</strong> follows<br />

the same structure as the 2010 <strong>Monitor</strong>, we have added new <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

We have reta<strong>in</strong>ed any valid <strong>in</strong>sights ga<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> previous research and<br />

deleted f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs that have become obsolete, especially where statistical<br />

data are concerned. We have also updated our survey of the research<br />

<strong>in</strong> Chapter 2 and added new <strong>in</strong>formation. This edition of the <strong>Monitor</strong><br />

therefore supersedes previous editions.

2<br />

Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICT<br />

2 - BENEFITS oF USING ICT<br />

What benefits can be derived from the balanced use of ICT <strong>in</strong><br />

education? This chapter discusses the results of our research on the<br />

benefits of ICT<br />

This year’s results confirm what we discovered last year: that ICT makes<br />

teach<strong>in</strong>g more effective, efficient, and appeal<strong>in</strong>g. It should be noted,<br />

however, that ICT (or more ICT) is not always the best alternative. Schools<br />

and teachers should start by tak<strong>in</strong>g a good look at the circumstances <strong>in</strong><br />

which it is be<strong>in</strong>g used. Po<strong>in</strong>ts to consider are the follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

• It is better to be realistic and set feasible goals.<br />

• The teacher plays a crucial role.<br />

• ICT raises new questions about pupil <strong>in</strong>dependence and the teacher’s<br />

role as a coach.<br />

• one size does not fit all: be sure to take differences <strong>in</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g styles<br />

<strong>in</strong>to account.<br />

• Coherence: relate the digital material to other material.<br />

After a brief description of the <strong>Kennisnet</strong> study (Section 2.1), we<br />

discuss the results by look<strong>in</strong>g at four learn<strong>in</strong>g strategies that are closely<br />

associated with pedagogical vision (Sections 2.2 – 2.6).<br />

2.1 <strong>Kennisnet</strong>’s research program<br />

This chapter presents a compilation of the results obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Knowledge of Value, <strong>Kennisnet</strong>’s research program. S<strong>in</strong>ce 2007, <strong>Kennisnet</strong><br />

has encouraged and funded research through this program, specifically by<br />

support<strong>in</strong>g studies that <strong>in</strong>vestigate which strategies work when us<strong>in</strong>g ICT<br />

<strong>in</strong> education and which do not.<br />

The program is demand-driven and education-driven; <strong>in</strong> other words,<br />

the research is based on questions that schools themselves are ask<strong>in</strong>g<br />

regard<strong>in</strong>g the effectiveness of a pedagogical concept. For example, can<br />

an <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard enhance teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a way that helps pupils<br />

learn more? And do pupils collaborate more closely if they make a video<br />

together? The program essentially welcomes any question concern<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

contribution ICT makes to achiev<strong>in</strong>g educational objectives.<br />

15

16<br />

We can describe research carried out on behalf of <strong>Kennisnet</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

“knowledge pyramid” (Figure 2.1). The pyramid consists of four levels:<br />

<strong>in</strong>spiration, existence, perception, and evidence. Every <strong>in</strong>novation <strong>in</strong><br />

education beg<strong>in</strong>s with an idea (<strong>in</strong>spiration). Some of these ideas can<br />

be turned <strong>in</strong>to reality (existence), and this is where the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong><br />

conditions play a crucial role. The job of the researcher is to clarify<br />

whether ICT will actually help produce the <strong>in</strong>tended benefits, whether<br />

teachers, pupils and parents recognize its added value (perception), and<br />

whether pupils <strong>in</strong> fact really learn more (evidence).<br />

In other words, we beg<strong>in</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g knowledge at the bottom of the<br />

pyramid, with an <strong>in</strong>spired idea as to how ICT can improve education. The<br />

idea is put <strong>in</strong>to practice and research exam<strong>in</strong>es whether it has lived up<br />

to expectations. The research results can <strong>in</strong> turn lead to better ideas, and<br />

to a new or adapted bottom level, for example by extend<strong>in</strong>g successful<br />

projects to <strong>in</strong>clude a larger group or try<strong>in</strong>g them out under other<br />

conditions, and by learn<strong>in</strong>g from projects that did not demonstrate the<br />

added value of ICT.<br />

Evidence – confirmed benefits<br />

Perception – perceived benefits<br />

Existence – implementation<br />

Inspiration – idea<br />

Teachers and pupils are enthusiastic; pupils<br />

are very motivated and feel more confident<br />

Pupils <strong>in</strong> groups 4 to 8 use Kurzweil software<br />

when they like, like a pair of read<strong>in</strong>g glasses<br />

Pupils weak <strong>in</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g let the computer read<br />

them texts (compensat<strong>in</strong>g)<br />

Figure 2.1: The knowledge pyramid<br />

The knowledge pyramid is made up of four hierarchical levels; each succeed<strong>in</strong>g<br />

level has greater evidentiary value. An example is given on the right (Luyten,<br />

<strong>2011</strong>b). This example concerns a school that uses a text-to-speech program to<br />

help dyslexic pupils with their read<strong>in</strong>g. The pupils can have the program read<br />

texts out loud to them. In the example, research has confirmed the school’s<br />

expectations. The results may lead to the program be<strong>in</strong>g used more widely.<br />

Example: Read<strong>in</strong>g with a computer program that<br />

reads texts out loud (Kurzweil)<br />

Pupils who learn to read us<strong>in</strong>g the read-aloud<br />

software are more motivated and self-confident

2 - BENEFITS oF USING ICT<br />

In this chapter, we show the relationship between the basic elements<br />

surveyed <strong>in</strong> our research program, cluster those elements and draw overall<br />

conclusions. We beg<strong>in</strong> at the bottom of the pyramid, with the ideas. We<br />

categorize these accord<strong>in</strong>g to two important approaches to education:<br />

knowledge transfer and knowledge construction (expla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Section 2.2).<br />

This allows us to sort out the promis<strong>in</strong>g ideas from the less promis<strong>in</strong>g<br />

ones and map expectations concern<strong>in</strong>g the use of ICT <strong>in</strong> education. We<br />

provide only a brief description here of the studies on which we have<br />

based our <strong>in</strong>sights. readers who would like more <strong>in</strong>formation should<br />

consult the bibliography at the end of this publication and visit<br />

onderzoek.<strong>kennisn</strong>et.nl/onderzoeken-totaal/overzicht. The various studies<br />

are listed there.<br />

2.2 Classify<strong>in</strong>g ICT applications by pedagogical vision<br />

We can roughly divide our <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>to the benefits of ICT <strong>in</strong>to two<br />

categories: ICT that supports knowledge transfer and ICT that supports<br />

knowledge construction (oECD, 2009).<br />

Knowledge transfer is a pedagogical approach <strong>in</strong> which the teacher<br />

conveys knowledge to the pupil <strong>in</strong> small steps, with the emphasis be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

on repetition and practice. The teacher decides what pupils should learn,<br />

and when. An extreme example of knowledge transfer is a lecture or a<br />

“prepackaged” lesson.<br />

In knowledge construction, the teacher facilitates learn<strong>in</strong>g as part of<br />

a process of <strong>in</strong>vestigation. The pupils are given the chance to acquire<br />

knowledge actively, <strong>in</strong>dependently and <strong>in</strong> collaboration with others by<br />

search<strong>in</strong>g for solutions. When assess<strong>in</strong>g pupil performance, the teacher<br />

looks not only at what pupils have learned but also at how they have<br />

learned it (Van Gennip, 2008).<br />

17

18<br />

Knowledge transfer Knowledge construction<br />

Structure offer<strong>in</strong>g knowledge <strong>in</strong> a clearly<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ed and structured (step-bystep)<br />

manner<br />

Tim<strong>in</strong>g Teacher (or computer) decides<br />

what knowledge pupils are given<br />

and when<br />

Epistemology Well-def<strong>in</strong>ed and solvable<br />

problems, with correct solutions<br />

Classroom<br />

situation<br />

Quiet and concentration <strong>in</strong><br />

classroom, attention focused on<br />

teacher<br />

Focus<strong>in</strong>g on the end product,<br />

facilitat<strong>in</strong>g the pupil’s process<br />

of <strong>in</strong>vestigation<br />

Pupil directs learn<strong>in</strong>g and is an<br />

active participant <strong>in</strong> knowledge<br />

acquisition<br />

Encourag<strong>in</strong>g pupils to search for<br />

new solutions<br />

Active work attitude, work<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependently and <strong>in</strong> collaboration,<br />

not limited to classroom<br />

Test<strong>in</strong>g Pupils tested on content Assessment of learn<strong>in</strong>g process<br />

Learn<strong>in</strong>g objective<br />

Acquir<strong>in</strong>g a knowledge of facts<br />

and concepts<br />

Develop<strong>in</strong>g the ability to<br />

conceptualize and reason<br />

Table 2.1: Compar<strong>in</strong>g knowledge transfer and knowledge construction (based on oECD, 2009,<br />

Chapter 4)<br />

Knowledge transfer and knowledge construction should be viewed as<br />

abstractions or idealizations (shown <strong>in</strong> Table 2.1). Pure forms seldom<br />

occur <strong>in</strong> reality, however, and <strong>in</strong> the classroom, teachers tend to use both<br />

– although Chapter 4 will show that teachers express a certa<strong>in</strong> or even a<br />

strong preference for knowledge transfer. It is expected, however, that<br />

knowledge construction will ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> importance.<br />

Knowledge transfer and knowledge construction us<strong>in</strong>g ICT<br />

The <strong>Kennisnet</strong> studies can easily be divided <strong>in</strong>to those concern<strong>in</strong>g<br />

knowledge transfer and those concern<strong>in</strong>g knowledge construction. It is<br />

useful to have a clear explanation of the difference between the two<br />

categories. Knowledge transfer <strong>in</strong>cludes such strategies as “<strong>in</strong>struction”<br />

and “structured practice”; knowledge construction <strong>in</strong>cludes such strategies<br />

as “<strong>in</strong>quiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g” and “learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn” (which will be<br />

expla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> detail <strong>in</strong> the sections below). ICT can be deployed <strong>in</strong> each<br />

of these strategies but the objectives will differ and so will the benefits.<br />

Table 2.2 lists the four above-mentioned (ideal) strategies along with a<br />

typical example of each one and a typical learn<strong>in</strong>g objective.

2 - BENEFITS oF USING ICT<br />

The rest of this chapter considers the follow<strong>in</strong>g question: what do we know<br />

about the added value of ICT for these four teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g strategies?<br />

Teach<strong>in</strong>g/<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

strategy<br />

Typical example of<br />

ICT use<br />

Transfer Instruction Enrich<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>struction by<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g images on <strong>in</strong>teractive<br />

whiteboard<br />

Construction<br />

Structured<br />

practice<br />

Inquiry-based<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Learn<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

learn<br />

repetition exercises on<br />

a computer<br />

Physics computer<br />

simulation<br />

Us<strong>in</strong>g video and a<br />

digital portfolio to<br />

encourage reflection<br />

Learn<strong>in</strong>g objective See<br />

Ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g new<br />

knowledge<br />

Consolidat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

knowledge, mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

it automatically<br />

accessible<br />

Understand<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and master<strong>in</strong>g<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>ciples<br />

Controll<strong>in</strong>g one’s<br />

own learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

process<br />

§ 2.3<br />

§ 2.4<br />

§ 2.5<br />

§ 2.6<br />

Table 2.2: <strong>Four</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g strategies and ICT use <strong>in</strong> each case (based on Lemke, 2006)<br />

2.3 ICT and <strong>in</strong>struction<br />

Instruction is the direct transfer of knowledge to a pupil, as it occurs <strong>in</strong><br />

traditional classroom teach<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

A reasonably large body of research has confirmed that ICT can help<br />

teachers transfer knowledge more effectively. This is particularly true for<br />

methods <strong>in</strong> which ICT adds someth<strong>in</strong>g to a teacher’s exist<strong>in</strong>g practices but<br />

does not change those practices fundamentally.<br />

Enhanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>struction<br />

ICT can help teachers enhance <strong>in</strong>struction by allow<strong>in</strong>g them to use visuals<br />

and audio, thereby <strong>in</strong>tensify<strong>in</strong>g the knowledge transfer process. one<br />

important lesson learned from previous research is that knowledge is<br />

transferred more effectively when visuals and audio are comb<strong>in</strong>ed. This<br />

effect – known as the multimedia pr<strong>in</strong>ciple – has been confirmed by<br />

various studies (Mayer, 2002; Van G<strong>in</strong>kel, 2009; Bus, 2009).<br />

19

20<br />

The <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard has proved to be an effective medium for<br />

enhanc<strong>in</strong>g traditional classroom <strong>in</strong>struction. Teachers who use visuals,<br />

audio, and video on the whiteboard to enhance their traditional classroom<br />

lessons help pupils remember the material and are more likely to hold<br />

pupils’ attention. Another advantage is that the teacher can reuse digital<br />

lessons and post them <strong>in</strong> the electronic learn<strong>in</strong>g environment (ELE), so<br />

that pupils can review the material later. The impact of an <strong>in</strong>teractive<br />

whiteboard can be boosted by us<strong>in</strong>g vot<strong>in</strong>g panels, for example to check<br />

whether pupils have actually understood the material and to make lessons<br />

more <strong>in</strong>teractive (Lemke, 2009).<br />

The results of studies on the use of the <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard <strong>in</strong> digital<br />

<strong>in</strong>struction are therefore largely positive. Teachers and pupils are<br />

generally very enthusiastic about the <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard. Provided<br />

they have a skilled teacher who has mastered the subject matter, the<br />

pedagogical methods, and the technology, pupils who receive <strong>in</strong>struction<br />

on the <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard do perform better (Fisser, 2007; Van Ast,<br />

2010; heemskerk, 2010; Somekh, 2007; Marzano, 2009; oberon, 2010).<br />

Texts read out loud by computer<br />

one very different way of us<strong>in</strong>g ICT <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>struction is to program a<br />

computer to read out loud. Primary schools <strong>in</strong> the Prov<strong>in</strong>ce of Gelderland<br />

offered dyslexic pupils a software program that read texts out loud. This<br />

turned out to work very well; it motivated pupils to read and helped build<br />

their self-confidence (Luyten, <strong>2011</strong>b).<br />

E-learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

E-learn<strong>in</strong>g means read<strong>in</strong>g with the help of ICT when the relevant<br />

participants are not <strong>in</strong> the same location and ICT is used to bridge the<br />

distance between them. The lessons can be synchronous (at the same time)<br />

or asynchronous (not at the same time).<br />

Examples of synchronous learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>clude hav<strong>in</strong>g an expert address a class<br />

via video-conferenc<strong>in</strong>g or distance teach<strong>in</strong>g for schools <strong>in</strong> regions with<br />

decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g populations (Van der Neut, 2008; Jonkman, 2008).

2 - BENEFITS oF USING ICT<br />

A good example of asynchronous e-learn<strong>in</strong>g is the Khan Academy<br />

(www.khanacademy.org/), which has more than 2000 <strong>in</strong>structional videos<br />

that pupils can watch whenever it suits them.<br />

A more radical form of e-learn<strong>in</strong>g is the digital tutor, an overall<br />

<strong>in</strong>struction program that pupils can work through with m<strong>in</strong>imal teacher<br />

<strong>in</strong>tervention. It is particularly popular <strong>in</strong> higher education (for example<br />

the open University of the Netherlands), but primary schools are also<br />

experiment<strong>in</strong>g with it. For example, some Dutch primary schools used a<br />

digital tutor for their English lessons (hovius, 2010). The tutors guided the<br />

pupils through a series of topics <strong>in</strong> English on the <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard,<br />

address<strong>in</strong>g them <strong>in</strong> native-speaker-quality English. The pupils also<br />

watched films and carried out assignments. The pupils who had received<br />

lessons from the digital tutor were just as motivated and performed just as<br />

well as the control group pupils who had been <strong>in</strong>structed by a teacher <strong>in</strong><br />

the traditional manner.<br />

There is little evidence that such e-learn<strong>in</strong>g methods actually improve<br />

teach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g, however (Lemke, 2009). What is certa<strong>in</strong> is that they<br />

require teachers to have outstand<strong>in</strong>g skills, for example so that they can<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> order <strong>in</strong> onl<strong>in</strong>e classes, check whether pupils understand the<br />

material, and relate the digital material to the regular material.<br />

2.4 Structured practice<br />

The po<strong>in</strong>t of knowledge transfer is to give pupils a solid knowledge base.<br />

Knowledge transfer <strong>in</strong>volves convey<strong>in</strong>g new knowledge to pupils (Section<br />

2.3), but it is also vital for that knowledge to “stick” and for pupils to be<br />

able to recall it immediately. The most suitable learn<strong>in</strong>g activity for this<br />

is practice (mak<strong>in</strong>g knowledge automatic). We def<strong>in</strong>e practic<strong>in</strong>g broadly<br />

to mean the rote memorization of facts (such as words), the application of<br />

learned rules (such as grammar rules) and skills exercises (such as learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to touch type).<br />

Positive results have been achieved with practice software, subject to the<br />

right conditions. A well-designed program should allow pupils to practice<br />

21

22<br />

at their own level and should motivate them to review the material<br />

<strong>in</strong>formally, even <strong>in</strong> their own time. It should also be easy for teachers to<br />

use.<br />

Practice at one’s own level<br />

one advantage of practic<strong>in</strong>g on the computer is that the software can<br />

adapt the material dynamically to the pupil’s knowledge, skills and needs.<br />

A pert<strong>in</strong>ent example is the “Clever Cramm<strong>in</strong>g” software program [Slim-<br />

Stampen]. It is based on research show<strong>in</strong>g that we remember facts best if<br />

we review them when we have almost forgotten them. The ideal moment<br />

differs from one person to the next and depends partly on the pupil’s<br />

prior knowledge. Software programs are able to identify that moment to a<br />

fair level of accuracy. “Clever Cramm<strong>in</strong>g” uses a pupil’s reaction speed to<br />

decide whether or not an exercise needs to be repeated. Studies show that<br />

pupils who work with this software do <strong>in</strong> fact remember facts better than<br />

those who decide for themselves when to study a list of words (Van rijn,<br />

2009).<br />

A computer program is also better than a worksheet at provid<strong>in</strong>g pupils<br />

with extra tutor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> areas <strong>in</strong> which they are weak. one example is a<br />

homework program <strong>in</strong> language and math [Muiswerk] that not only gives<br />

pupils exercises to do, but also offers them new material. It gives pupils<br />

direct feedback and keeps track of which material they have and have<br />

not mastered. Small-scale quasi-experimental research shows that pupils<br />

are capable of work<strong>in</strong>g on such exercises <strong>in</strong>dependently and complet<strong>in</strong>g<br />

spell<strong>in</strong>g and read<strong>in</strong>g comprehension assignments with the help of an<br />

assistant teacher (Meijer, 2009).<br />

Informal learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Primary schools are mak<strong>in</strong>g grow<strong>in</strong>g use of Smart Boards (a brand of<br />

<strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard) or SkoolMates (computers designed especially for<br />

children), with pupils (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g pre-schoolers) us<strong>in</strong>g them to complete<br />

<strong>in</strong>teractive exercises or play educational games. The pupils do not<br />

learn any better than pupils who do not have access to these tools, but<br />

teachers feel that they enhance their lessons and extend their pedagogical<br />

repertoire (Luyten, <strong>2011</strong>; heemskerk, <strong>2011</strong>).

2 - BENEFITS oF USING ICT<br />

one good example of us<strong>in</strong>g ICT for <strong>in</strong>teractive practice is an experiment<br />

carried out at De Arabesk primary school <strong>in</strong> Arnhem. Pupils there worked<br />

<strong>in</strong> twos to complete math exercises on the <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard. The<br />

sums were designed to get pupils actively <strong>in</strong>volved: they required them to<br />

drag parts of the equation from one place to another, take turns writ<strong>in</strong>g<br />

on the whiteboard, consult one another and figure th<strong>in</strong>gs out together.<br />

They also required pupils to stretch out their arms <strong>in</strong> order to fill <strong>in</strong> an<br />

answer or po<strong>in</strong>t to someth<strong>in</strong>g. The study showed that pupils did <strong>in</strong>deed<br />

get actively <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> do<strong>in</strong>g the sums, used <strong>in</strong>quiry-based methods,<br />

collaborated a great deal, and enjoyed work<strong>in</strong>g on the assignments. They<br />

also performed better (Coetsier, 2009).<br />

A grow<strong>in</strong>g number of practice programs now use the same motivation<br />

techniques applied <strong>in</strong> commercial games, for example tension and<br />

competition. This is prov<strong>in</strong>g to be successful. Children who practice their<br />

sums on a gam<strong>in</strong>g computer are better at math and do sums more quickly<br />

(Luyten, <strong>2011</strong>b), and the results of the Farmville-like Math Garden game<br />

also look promis<strong>in</strong>g (heemskerk, <strong>2011</strong>). Both games have a competitive<br />

element and require pupils to work under time pressure (for example to<br />

create the nicest possible garden <strong>in</strong> the shortest time possible).<br />

Ease of use<br />

Primary schools <strong>in</strong> Emmen compared tests given on paper with digital<br />

tests and came to the follow<strong>in</strong>g conclusions: digital tests are a reliable<br />

replacement for tests on paper, save time, and are easy to use (Luyten,<br />

<strong>2011</strong>j).<br />

Underly<strong>in</strong>g conditions<br />

Teachers who have their pupils practice at their own level on the computer<br />

need to know when those pupils require extra help or support and when<br />

they do not. After all, the advantage of computer software is that it is the<br />

computer that decides who is given what material to practice and when.<br />

Not every teacher likes that. Effective use of computers means that the<br />

teacher must familiarize him or herself with a new role, but it also means<br />

that the computer program must live up to expectations.<br />

23

24<br />

It is therefore important for practice programs to be well designed:<br />

• A practice program must allow pupils to practice at their own level.<br />

If the exercises are too difficult or unrelated to the subject matter<br />

they have studied, the pupils will get stuck and thus require a lot of the<br />

teacher’s attention (ritzen, 2010).<br />

• Pupils have trouble work<strong>in</strong>g with practice programs that are<br />

constrict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> their structure. If they get stuck, they want to be able to<br />

skip a sum, for example, and go on to the next one (Sneep, 2010).<br />

• The program must not have any technical problems, and absolutely no<br />

mistakes <strong>in</strong> the content itself. Unfortunately, such problems are still too<br />

common (see for example Luyten, <strong>2011</strong>i; heemskerk, <strong>2011</strong>).<br />

Because practice programs have not yet been perfected and often do<br />

not satisfy these requirements, it is important for teachers to keep<br />

accurate digital records on pupil progress. That does not always happen,<br />

however. A study by Vijfeijken (2010) describes a digital pupil <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

management system for development-based teach<strong>in</strong>g that is easy for<br />

teachers to use.<br />

Even if the practice program is well designed, the teacher’s role should<br />

not be limited to monitor<strong>in</strong>g. he or she must also take the pupils’ differ<strong>in</strong>g<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g styles <strong>in</strong>to account. A grow<strong>in</strong>g volume of research po<strong>in</strong>ts to the<br />

differential effects of practice programs (i.e. their <strong>in</strong>fluence differs from<br />

one pupil to the next). For example, language tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programs appear to<br />

have a greater impact on some pre-schoolers (positive or negative) than on<br />

others. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the researchers, these pre-schoolers are <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sically<br />

more sensitive than other children to environmental factors (such as<br />

feedback from a teacher or a computer program), <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the impact<br />

of feedback (Kegel, <strong>2011</strong>). More generally speak<strong>in</strong>g, we expect that some<br />

pupils will be better able to work with ICT than others. It is the teacher’s<br />

job to provide the right amount of guidance.<br />

Another important job for the teacher is to cont<strong>in</strong>ue to show how the<br />

practice material relates to the rest of the material covered. Children will<br />

learn very little if all they do is practice. In order to master a language,

for example, they must be able to use the words they have learned <strong>in</strong> a<br />

language-rich context (Suhre, 2008; Corda, 2010).<br />

2 - BENEFITS oF USING ICT<br />

In short, it is precisely when ICT enables pupils to work more<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependently, that pupils <strong>in</strong> fact need the teacher’s <strong>in</strong>put more than ever.<br />

ICT does not replace the teacher but rather creates new relationships,<br />

between the pupil, the subject matter, the ICT application itself, and the<br />

teacher. It raises questions about the balance between pupils work<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependently, the amount of control exercised by the software, and the<br />

amount of control that the teacher has over the learn<strong>in</strong>g process.<br />

2.5 Inquiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Inquiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g means teach<strong>in</strong>g methods <strong>in</strong> which pupils are more<br />

or less free to look up the answer to a question, search for <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

about a topic, study a concept, or develop skills. The problems they are<br />

told to <strong>in</strong>vestigate are often complex ones that can be answered <strong>in</strong> several<br />

ways. The process – that is, how the pupil arrives at the solution – is one<br />

of the learn<strong>in</strong>g objectives.<br />

ICT can offer considerable advantages <strong>in</strong> this respect, but as <strong>in</strong> the case<br />

of practice programs, applications that support <strong>in</strong>quiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

require at the very least a precise, professional, and pedagogically<br />

relevant design…as well as the constant attention of the teacher.<br />

Computer simulations<br />

Computer simulations enable pupils to experiment <strong>in</strong> an environment –<br />

a model – that imitates reality. They give pupils the chance to develop<br />

practical skills, for example learn<strong>in</strong>g about dredg<strong>in</strong>g with a dredg<strong>in</strong>g<br />

simulator (oomens, <strong>2011</strong>), or to familiarize themselves with the basic<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of research, such as develop<strong>in</strong>g a hypothesis (De Jong, 2009).<br />

Games may also be classified as computer simulations. Some games are<br />

developed especially for the education sector, but pupils can even learn<br />

from store-bought games if they have a good teacher (Van rooij, 2010a;<br />

Verheul, 2009; Claessens, <strong>2011</strong>a).<br />

25

26<br />

Pupils learn skills and acquire knowledge <strong>in</strong> simulations. The simulations<br />

must have a properly balanced design, however – not too structured<br />

and not too amorphous. Pupils must have sufficient prior knowledge<br />

to make any headway <strong>in</strong> such an environment, and the simulation itself<br />

must provide scaffolded <strong>in</strong>struction, i.e. support the pupils and offer<br />

them sufficient guidance (hagemans, 2008; Van de Schaar, 2009). It takes<br />

time to develop a powerful simulation or game. It is also expensive and<br />

requires considerable professional expertise, with technicians, designers,<br />

pedagogical experts, and subject specialists all work<strong>in</strong>g together (De Jong,<br />

2009a).<br />

one unusual example of a simulation is a four-dimensional globe that can<br />

move backwards and forwards <strong>in</strong> time and accurately represents the world<br />

<strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>iature (cities, countries, oceans). Pupils were allowed to use the<br />

globe to learn topography. This did not work very well, however; pupils<br />

made better progress study<strong>in</strong>g a textbook, <strong>in</strong> part because the globe was<br />

not designed for this particular purpose and could not be used efficiently<br />

(Luyten, <strong>2011</strong>g).<br />

Mean<strong>in</strong>gful context<br />

The best context for <strong>in</strong>quiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g is one that is rich and<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gful. ICT can provide such a context. Pupils at a primary school, for<br />

example, used a digital sensor when study<strong>in</strong>g various subjects to measure<br />

light, sound and temperature (Luyten, <strong>2011</strong>a). other pupils <strong>in</strong> preparatory<br />

vocational education who wanted to specialize <strong>in</strong> ICT were given study<br />

material <strong>in</strong> basic subjects (such as Dutch and mathematics) that had been<br />

<strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to vocational subjects (Claessens, <strong>2011</strong>b). In yet another<br />

example, a mobile phone was used to bridge the distance between formal<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g at school and <strong>in</strong>formal learn<strong>in</strong>g outside the classroom (Sandberg,<br />

2010). In none of these cases did the use of ICT <strong>in</strong> a mean<strong>in</strong>gful context<br />

produce additional learn<strong>in</strong>g effects. Additional effects were found,<br />

however, when pupils downloaded educational games to their mobile<br />

phones. Because they were allowed to take the phones home with them,<br />

they cont<strong>in</strong>ued play<strong>in</strong>g the games after school hours and consequently got<br />

better marks.

Pupils surf<strong>in</strong>g the Internet<br />

% of pupils<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

58<br />

PRIM<br />

43<br />

SEC<br />

85<br />

VET<br />

2 - BENEFITS oF USING ICT<br />

Search<strong>in</strong>g the Internet<br />

The Internet is an almost <strong>in</strong>exhaustible source of <strong>in</strong>formation and as such<br />

is used a great deal <strong>in</strong> education (Figure 2.2).<br />

Figure 2.2: Percentage of pupils who teachers say make at least weekly use of the Internet<br />

at school for educational purposes (TNS NIPo, 2010)<br />

The Internet is not always a good learn<strong>in</strong>g environment, however. Pupils<br />

seldom subject Internet sources to a critical evaluation. They ma<strong>in</strong>ly look<br />

at whether the <strong>in</strong>formation is available <strong>in</strong> Dutch, whether the site can<br />

answer their question quickly, and whether it looks attractive. Information<br />

skills are <strong>in</strong>dispensable if the po<strong>in</strong>t is to ga<strong>in</strong> knowledge from the<br />

Internet (Kuiper, 2007; Walraven, 2008; <strong>2011</strong>), but so far, schools have not<br />

attempted to teach pupils such skills <strong>in</strong> any systematic fashion (see Box).<br />

one good way to help pupils acquire the necessary <strong>in</strong>formation skills is by<br />

means of webquests (Droop, <strong>2011</strong>).<br />

27

28<br />

The debate concern<strong>in</strong>g the importance of <strong>in</strong>formation skills<br />

and twenty-first century skills<br />

The examples given <strong>in</strong> Chapter 2 concern ICT applications that support<br />

teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g, for example a practice program, a digital portfolio, or<br />

the Internet. But to use such applications, pupils must have the necessary<br />

skills, i.e. ICT or <strong>in</strong>formation skills. Information skills are so fundamental,<br />

both <strong>in</strong> educational sett<strong>in</strong>gs and <strong>in</strong> society <strong>in</strong> general, that they have<br />

become the subject of a major <strong>in</strong>ternational debate. What skills are we<br />

talk<strong>in</strong>g about, and why are they so important?<br />

It is not entirely clear which skills are thought to be <strong>in</strong>formation skills. In<br />

the most general sense, they consist of all the skills that allow us to use ICT<br />

effectively <strong>in</strong> order to function normally <strong>in</strong> today’s ICT-driven knowledge<br />

society. This goes further than basic skills such as read<strong>in</strong>g comprehension<br />

or ICT skills such as the ability to use a computer. Information skills also<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude skills that enable us to deal responsibly, critically and creatively<br />

with ICT (Van den Berg, 2010; Boelens, 2010; Maddux, 2009; Van Vliet,<br />

<strong>2011</strong>). Someone who has <strong>in</strong>formation skills is aware of security risks,<br />

can evaluate sources, and can produce <strong>in</strong>formation himself. he is also,<br />

however, aware of the ethical and legal aspects associated with the use of<br />

ICT and with <strong>in</strong>formation dissem<strong>in</strong>ated on the Internet and through social<br />

media. These wide-rang<strong>in</strong>g skills are sometimes referred to as “twentyfirst<br />

century skills” (Voogt, 2010b).<br />

Information skills are becom<strong>in</strong>g more and more important. It is grow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly clear, both <strong>in</strong> the Netherlands and abroad, that <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

skills are set to become the “new literacy” that every person must master<br />

(Anderson, 2008; Johnson, 2010). That means that <strong>in</strong>formation skills will<br />

soon be just as vital as read<strong>in</strong>g, writ<strong>in</strong>g, and arithmetic. Anyone who has<br />

not mastered <strong>in</strong>formation skills will be at risk of becom<strong>in</strong>g marg<strong>in</strong>alized<br />

(European Commission, 2010; oECD, 2010a; Anderson, 2008; Boelens, 2010;<br />

Ten Brummelhuis, 2010).

2 - BENEFITS oF USING ICT<br />

The education sector has not concerned itself with this problem <strong>in</strong> any<br />

consistent manner. It is wrongly assumed that youngsters are so handy<br />

with computers that schools do not need to teach them how to search for<br />

and select <strong>in</strong>formation on the Internet. By way of illustration: a recent<br />

study has shown that only one out of five primary and secondary school<br />

teachers gives frequent or very frequent lessons on us<strong>in</strong>g Internet sources<br />

selectively (Van Gennip, <strong>2011</strong>a; <strong>2011</strong>b).<br />

That means that pupils’ digital literacy currently depends ma<strong>in</strong>ly on the<br />

situation at home and what their school happens to teach them. Unlike<br />

most of the other European Union Member States (Eurydice, <strong>2011</strong>), the<br />

Netherlands has not def<strong>in</strong>ed learn<strong>in</strong>g objectives for the digital skills that<br />

young people need to survive <strong>in</strong> the twenty-first century.<br />

Studies are mak<strong>in</strong>g it <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly clear, however, that many pupils are<br />

<strong>in</strong>capable of us<strong>in</strong>g the Internet effectively as a learn<strong>in</strong>g resource (oECD,<br />

2010a; Walraven, <strong>2011</strong>). In other words, we tend to overestimate pupils’<br />

computer skills (Kanters, 2009). Although many pupils have mastered a<br />

number of ICT skills, that does not mean that they are capable of us<strong>in</strong>g ICT<br />

to learn or of us<strong>in</strong>g it responsibly, critically, and creatively.<br />

2.6 Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn<br />

“Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn” covers various teach<strong>in</strong>g methods that focus primarily<br />

on the pupil’s learn<strong>in</strong>g process and his or her awareness of that process.<br />

The content is subord<strong>in</strong>ate to the process. There is some overlap between<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn and <strong>in</strong>quiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

We still know too little about the added value of applications that support<br />

this type of learn<strong>in</strong>g. Schools are experiment<strong>in</strong>g with ICT <strong>in</strong> this respect,<br />

but the work<strong>in</strong>g methods are still too open-ended to study their effects.<br />

29

30<br />

Competence-based professional environments<br />

Environments that simulate professional sett<strong>in</strong>gs are particularly <strong>in</strong><br />

demand <strong>in</strong> vocational education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g because they allow pupils to<br />

carry out the duties that they will have to perform later <strong>in</strong> their careers<br />

(see also Chapter 3). Among the key learn<strong>in</strong>g objectives are the pupil’s<br />

ability to plan and control his or her own learn<strong>in</strong>g process.<br />

one example of such an environment is Schonenvaart. In this simulation,<br />

pupils take on the role of an account manager and carry out a number of<br />

assignments. The effectiveness of the environment has been shown to be<br />

limited. Pupils do not see the relevance of the assignments, those who<br />

have trouble plann<strong>in</strong>g and who do not feel motivated show no improvement<br />

on these po<strong>in</strong>ts, and only a small percentage of the assignments are ever<br />

handed <strong>in</strong>. In particular, the environment offers pupils who are already<br />

hav<strong>in</strong>g trouble at school very few benefits. It puts enormous demands on<br />

the teacher’s time and energy because he or she must cont<strong>in</strong>ue to monitor<br />

pupils closely (Coetsier, 2008). We can draw similar conclusions from a<br />

study carried out by Dieleman (2010) <strong>in</strong>to projects concern<strong>in</strong>g “mean<strong>in</strong>gful<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g” and the realistic learn<strong>in</strong>g environment LINK2 (Coetsier, <strong>2011</strong>).<br />

once aga<strong>in</strong>, it was not easy to put the <strong>in</strong>tended teach<strong>in</strong>g method <strong>in</strong>to<br />

practice; pupils became demotivated, and the results were disappo<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Reflection and ICT<br />

When teachers apply methods that focus on knowledge construction, it is<br />

important that their pupils th<strong>in</strong>k about how they themselves learn and<br />

acquire general skills. Schools are experiment<strong>in</strong>g with various ICT tools<br />

that will stimulate such reflection skills.<br />

one such tool is the digital portfolio. Pupils save their work there, receive<br />

feedback on their assignments, and can see at a glance where they stand.<br />

Some schools are extend<strong>in</strong>g such applications by giv<strong>in</strong>g all their pupils a<br />

laptop, so that they can access their digital portfolio whenever they like<br />

(Weijs, 2010).<br />

other methods that stimulate reflection <strong>in</strong>volve hav<strong>in</strong>g pupils record their<br />

presentation on video and discuss it with their classmates (Verbeij, 2009),<br />

or hav<strong>in</strong>g them keep a weblog (see Wopereis, 2009).

2 - BENEFITS oF USING ICT<br />

There have been only a few studies <strong>in</strong>to such tools. Because many of the<br />

applications are still <strong>in</strong> the draw<strong>in</strong>g board stage, the po<strong>in</strong>t of the research<br />

is usually to come up with a work<strong>in</strong>g design. As for research <strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the applications’ benefits, the results have so far been ambiguous. one<br />

experiment <strong>in</strong> which pupils used a digital video camera to produce their<br />

own school news program did not demonstrably improve their knowledge<br />

or skills (Luyten, <strong>2011</strong>e). Neither did the use of digital portfolios produce<br />

any demonstrable benefits (see for example the study <strong>in</strong>to digital<br />

portfolios <strong>in</strong> Meijer, 2009 or the study by Van Gennip, 2009), although that<br />

could be because the digital portfolios studied were not entirely functional<br />

yet. In addition, the learn<strong>in</strong>g objectives for these applications are not<br />

always clearly def<strong>in</strong>ed, mak<strong>in</strong>g it difficult to assess their effects.<br />

Computer-supported collaborative learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Willemsen asked teachers to consider five situations <strong>in</strong> which pupils were<br />

engaged <strong>in</strong> computer-supported collaborative learn<strong>in</strong>g (CSCL), rang<strong>in</strong>g<br />

from relatively simple arrangements where pupils sat down together at a<br />

computer to more complex arrangements where pupils collaborated while<br />

each one was at home work<strong>in</strong>g on his or her own computer. Teachers<br />

doubted whether such applications would be effective; they felt they did<br />

not have enough control over the learn<strong>in</strong>g situation and did not see CSCL<br />

as be<strong>in</strong>g of equal value to a normal lesson situation (Willemsen, 2010).<br />

2.7 Summary<br />

• ICT can make teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g more efficient, more effective, and more<br />

<strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g. Whether it <strong>in</strong> fact does so depends on how well the teacher<br />

is able to l<strong>in</strong>k the subject matter, the ICT application, and the pupil.<br />

• ICT has generally been found to produce greater results when used<br />

for knowledge transfer (<strong>in</strong>struction, practice) than for knowledge<br />

construction (<strong>in</strong>quiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn). In terms<br />

of the knowledge pyramid, many of the applications <strong>in</strong>tended for<br />

knowledge construction have not gone beyond the <strong>in</strong>spiration and<br />

existence stages. Applications <strong>in</strong>tended for knowledge transfer are more<br />

likely to reach the perceived benefits and evidence stages. however,<br />

the benefits may be easier to perceive because the learn<strong>in</strong>g objectives<br />

associated with knowledge transfer are more clearly def<strong>in</strong>ed and<br />

because there are more proven assessment <strong>in</strong>struments available.<br />

31

32<br />

• ICT can be conducive to knowledge transfer, as many examples show.<br />

The various applications share a number of features: they do not<br />

fundamentally alter teach<strong>in</strong>g, for example, and are relatively low<br />

threshold. For example, ICT adds someth<strong>in</strong>g (such as visual material)<br />

or replaces part of the lesson (the practice worksheet). Even so, such<br />

applications often take more time and energy than teachers may at<br />

first expect, especially if the computer takes over part of the teach<strong>in</strong>g<br />

process (as <strong>in</strong> the case of a practice program).<br />

• In terms of knowledge construction, ICT is still largely unexplored<br />

territory and its added value is more difficult to demonstrate.<br />

Designers are wrestl<strong>in</strong>g with such questions as: how much structure<br />

and guidance should an environment give pupils, and how can teachers<br />

control a learn<strong>in</strong>g process that takes place on a computer or network?<br />

When ICT was first <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> education, the suggestion was made that<br />

ICT might at some po<strong>in</strong>t even replace teachers. research results <strong>in</strong>dicate<br />

that the opposite is true. The more powerful the ICT tool, the more<br />

<strong>in</strong>dispensable the teacher. ICT creates a new relationship between pupils,<br />

subject matter, and teachers, forc<strong>in</strong>g us to exam<strong>in</strong>e the balance between<br />

the work that the pupil does on his own, how much the software controls<br />

that work, and how much the teacher controls the pupil’s learn<strong>in</strong>g process.<br />

The latter makes huge demands on teachers: they must keep a close eye<br />

on the progress of pupils work<strong>in</strong>g on their own, take pupils’ differ<strong>in</strong>g<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g styles <strong>in</strong>to account, and show pupils how the material they are<br />

study<strong>in</strong>g on the computer relates to other learn<strong>in</strong>g material.

3<br />

ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g<br />

3 - ICT IN TEAChING<br />

It is no longer possible to imag<strong>in</strong>e teach<strong>in</strong>g without ICT. Although<br />

computer use has not become as widespread as teachers and school<br />

managers had expected, teachers still assume that their use of ICT<br />