Fothergilla - Rick Darke

Fothergilla - Rick Darke

Fothergilla - Rick Darke

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

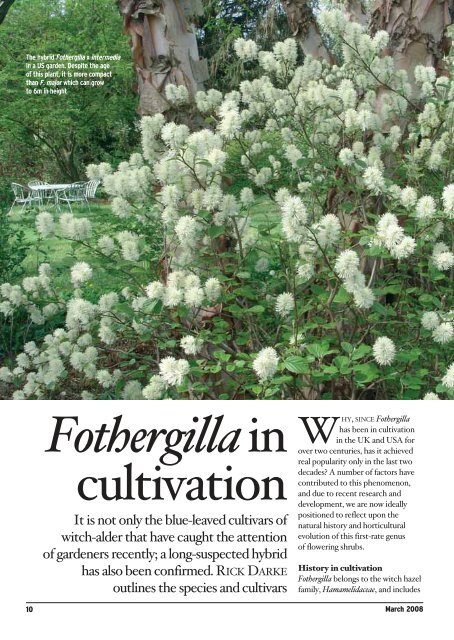

The hybrid <strong>Fothergilla</strong> x intermediain a US garden. Despite the ageof this plant, it is more compactthan F. major which can growto 6m in height<strong>Fothergilla</strong> incultivationIt is not only the blue-leaved cultivars ofwitch-alder that have caught the attentionof gardeners recently; a long-suspected hybridhas also been confirmed. RICK DARKEoutlines the species and cultivarsWHY, SINCE <strong>Fothergilla</strong>has been in cultivationin the UK and USA forover two centuries, has it achievedreal popularity only in the last twodecades? A number of factors havecontributed to this phenomenon,and due to recent research anddevelopment, we are now ideallypositioned to reflect upon thenatural history and horticulturalevolution of this first-rate genusof flowering shrubs.History in cultivation<strong>Fothergilla</strong> belongs to the witch hazelfamily, Hamamelidaceae, and includes10March 2008

ThePlantsmanonly two species, F. gardenii andF. major, both native to southeasternNorth America. Although thecommon name witch-alder is mostoften encountered in literature, itis rarely spoken: <strong>Fothergilla</strong> servesequally well as botanical andcommon name.The genus name honours Dr JohnFothergill (1712–1780), an EnglishQuaker physician whose 18th-centuryEssex garden garden included one ofthe earliest, most extensive collectionsof North American indigenousplants. Fothergill was the patron ofWilliam Bartram’s botanical explorationsof southeastern North<strong>Rick</strong> <strong>Darke</strong>America and he corresponded withother early botanists exploring theNew World flora, including DrAlexander Garden (1730–1791).Garden, a Scottish physician andzoologist, settled in Charleston,South Carolina in 1752 and for morethan twenty years devoted his sparetime to collecting regional flora andfauna, corresponding with andsending specimens to John Ellis inLondon and Linnaeus in Sweden.Garden is responsible for firstdiscovering <strong>Fothergilla</strong>, collecting anddescribing the species we now knowas F. gardenii, and introducing it toEngland by 1765. The discovery andintroduction of F. major is moreobscure; however, it was in cultivationin England by the 1780s.Following a brief period ofpopularity around the time of theirintroduction, both species weresparingly cultivated through the 19thcentury and for most of the 20th,though prominent horticulturistsperiodically attempted to drawattention to <strong>Fothergilla</strong>. CharlesSargent began promoting F. gardeniiin Garden and Forest in 1895, notingthat it had proved cold-hardy at theArnold Arboretum and suggesting‘few shrubs present a more curiousand beautiful effect than <strong>Fothergilla</strong>when it is covered in flowers. Itshabit is excellent, too, and its foliageis abundant and rich in color’(Sargent 1895). Richard Weaverprofiled the fothergillas in Arnoldiain 1971, noting that they remainedundeservedly little known and thatthere were not yet any namedhorticultural varieties of eitherspecies (Weaver 1971). Michael Dirrand Harrison Flint promoted<strong>Fothergilla</strong> in numerous books andarticles in the 1970s and early 1980s,but despite such efforts, <strong>Fothergilla</strong>generally remained obscurecuriosities, generally unappreciated,unavailable, and under-utilised. Itwould take the inadvertenthybridisation of the two species,nearly two centuries after theirdiscovery, to propel <strong>Fothergilla</strong>toward real celebrity.Two distinct speciesUnderstanding modern fothergillasbegins with a fresh look at thespecies’ natural histories, culturalrequirements and horticultural traits.Though thoroughly confused inrecent garden literature, F. gardeniiand F. major could hardly be moredistinct. The two species varydramatically in the size of theirphysical characters and there is nooverlap in their natural ranges.<strong>Fothergilla</strong> gardeniiOften known as dwarf fothergillabut perhaps best called coastalfothergilla, F. gardenii is restricted tothe coastal plain of North Carolina,South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama,and the Florida panhandle (Sorrie etal. 2006, Weakley 2006).Uncommon or rare over most of itsrange, this species is found in transitionalzones from wet pine savannasto moist shrub-bogs properly calledpocosins. Pocosins typically occupypoorly drained ground and are fed bygroundwater seeps. Pocosin soilstend to be deep, sandy, peaty, acidicand nutrient deficient. The soils areusually saturated although they aresubject to brief dry spells whenextended droughts lower watertables. Fire is an essential element inpocosin ecosystems and is importantin maintaining the relatively open,sunny conditions preferred by shrubssuch as F. gardenii, which is tolerantof burning as long as its roots areperennially moist.Although community mixes varywith moisture, shade and fire frequency,woody species often growingin association with F. gardenii includePinus serotina, Magnolia virginiana, ➤March 2008 11

GENUS PROFILEAcer rubrum, Chamaecyparis thyoides,Persea palustris, Smilax laurifolia,Kalmia cuneata, Myrica cerifera,Gaylussacia frondosa, Lyonia ligustrina,Ilex glabra, Cyrilla racemiflora, Clethraalnifolia, Viburnum nudum, Aroniaarbutifolia and Amelanchier obovalis.<strong>Fothergilla</strong> gardenii is low-growing,typically attaining only 60–90cm inheight and often suckering to equalor greater spread. The pubescent,green to blue-green leaves arerelatively small, ranging in lengthfrom 2 to 6cm and in width from1.5 to 5cm. The leaf bases are alwayssymmetric and the margins areentire in the lower portion andtoothed in the upper. Floweringoccurs in early spring before theleaves unfold. In native habitat thisis typically early to mid April. Highlyconspicuous on still-naked branches,the 2 to 3cm tall inflorescencesconsist of dense terminal spikes ofminute flowers. <strong>Fothergilla</strong>s aremonoecious, with male and femaleflowers occurring separately withinthe spikes. Petals are entirely lackingand even the sepals are greatly12<strong>Fothergilla</strong> gardenii ‘Blue Mist’ (top) was one of the earliest blue-leaved cultivars to be selected but it isnot particularly vigorous. It exhibits the low-growing habit of the typical species (in flower, above)reduced. Only the male flowers haveshowy parts, and these are the brightivory-white filaments of the stamens,each of which is topped by tinyyellow anthers. The inflorescencesare strongly and delightfully fragrant,with a honey-like scent that carriesfar on spring breezes. Autumn colourMarch 2008<strong>Rick</strong> <strong>Darke</strong> <strong>Rick</strong> <strong>Darke</strong>

ThePlantsmanSome selections of <strong>Fothergilla</strong> gardenii show autumn colour but this species rarely exceeds 90cm in heightvaries among seedlings and with environmentalconditions, from unremarkableyellow-green to vibrant yellow,apricot, burgundy and crimson.In cultivation, F. gardenii has provedthe less adaptable of the two speciesthough it can be a fine performer ifprovided proper conditions. Thoughusually cold-hardy to USDA zone 5,it is much more subject to winterdamage than F. major. It absolutelyrequires acidic, well-drained butcontinually moist soil for vigorousgrowth and longevity. It is a consistentlypoor performer in heavy,alkaline soils subject to drought. Itthrives in the climates of NorthAmerica’s Pacific Northwest andnorthern Europe if provided acidicconditions. In warmer, drier regionsit does better when sited in partshade, though flowering is alwaysmost profuse in sun.<strong>Fothergilla</strong> gardenii is the moreprolific seeder, producing manywoody capsules typically with twofertile seeds each. It can be propagatedby seed or by softwood cuttings.Cultivars of F. gardeniiF. gardenii ‘Appalachia’ is vigorousyet compact, to 60cm tall withstrong orange-red autumn colour.F. gardenii ‘Bill’s True Dwarf’ isamong the larger selections of thisspecies, growing to 1m tall, withblue-green summer foliage and goodautumn colour.F. gardenii ‘Blue Mist’ is one of theearliest named cultivars and one ofthe few that has always correctlybeen identified as F.gardenii. Introducedby the Morris Arboretum inPhiladelphia, it remains distinctivefor its glaucous blue summer foliage.The colour is not nearly as strong asF. x intermedia ‘Blue Shadow’ but it isstill quite pleasing. Compact, to80cm tall, it has low vigour and noappreciable autumn colour, but canbe a valuable landscape shrub inoptimum cultural conditions.F. gardenii ‘Harold Epstein’ is trulydiminutive. Compact and barely40cm tall with green summerfoliage, it has better vigour andautumn colour than ‘Jane Platt’ inwarmer climates . It was named forcelebrated rock gardener HaroldEpstein and popularised by theArnold Arboretum.F. gardenii ‘Jane Platt’ is anotherolder cultivar that has always beencorrectly identified as F.gardenii.Green-leaved and compact, to 60cmtall with lax stems, it is durable andvigorous with good autumn colour inthe Pacific Northwest but much lessso in warmer climates. It originatedin the Portland, Oregon, garden ofJane and John Platt.<strong>Fothergilla</strong> majorCalled mountain or large fothergilla,F. major, is a highland speciestypically occurring at elevations of500m and above, primarily in themountains of North Carolina, SouthCarolina, Tennessee, Georgia andAlabama, with disjunct populationsin Arkansas and limited occurrencein the North Carolina Piedmontfoot hills (Weakley 2006). It isuncommon but often locallyabundant, spreading by suckers toform large masses.Its mountain habitats range frommature but somewhat open mesicforests to, most commonly, ➤March 2008 13Richard Bloom

GENUS PROFILE<strong>Rick</strong> <strong>Darke</strong>Providing reliable autumn colour, <strong>Fothergilla</strong> x intermedia ‘Mount Airy’ is easy to propagate by cuttingsexposed ridges with thin, rocky,acidic soils and a relatively highincidence of fires. In such sitesplants are often exposed toprolonged dry conditions in summer,though these are mitigated bytypically cool night temperatures.At lower Piedmont elevations itprefers cliff-like, cooler north-facingslopes. Woody species occurringwith F. major in mountain habitatsinclude Pinus pungens, P. virginiana,Quercus coccinea, Q. prinus, Acerrubrum, Liriodendron tulipifera,Oxydendrum arboreum, Halesiatetraptera, Magnolia acuminata,Magnolia fraseri, Nyssa sylvatica,Kalmia latifolia and Hamamelisvirginiana, which in its vegetativestate is easily mistaken for <strong>Fothergilla</strong>due to its remarkably similar foliage.<strong>Fothergilla</strong> major is a large, multistemmedshrub capable of exceeding6m in height. The leaves are alsolarge – usually up to 13 cm long and6 to 11cm wide – and the leaf basesare strongly asymmetric. The foliageis typically green and less pubescentthan that of F. gardenii.Plants with fully glabrous leaveshave in the past been segregated asF. monticola, however this name isno longer recognised in the US,either for wild or cultivated plantsand all such material is included inF. major. The name persists in theUK, as Monticola Group, but thevariation seen may be just clonalrather than representing a consistenttaxon (Bean 1988).In its native habitat, F. majorflowers later than F. gardenii, typicallytowards the end of April, primarilydue to cooler conditions at highelevations. When in cultivationtogether the two species bloomnearly simultaneously.The inflorescences are much likethose of F. gardenii but are significantlylarger, with spikes up to 5cm tall.Autumn colour is variable but is reliablyvivid, ranging from clear yellowthrough apricot and orange to crimsonand dark burgundy. Individualshrubs often exhibit all these coloursover a few sunny autumn weeks.<strong>Fothergilla</strong> major is tolerant of awider, often more stressful range ofconditions in its native habitats thanF. gardenii and this translates intomuch greater adaptability in cultivation.It has greater cold hardiness,often proving reliable into USDAzone 4. It grows most vigorously inwell-drained organic soil but willtolerate heavier soils with onlymoderate drainage, and though itappreciates regular moisture it iscapable of withstanding considerabledry periods. It prefers acidicconditions but performs adequatelyin neutral to slightly alkaline soils.Though its height in cultivationrarely exceeds 3m, it is still a fairlylarge shrub with limited utility forsmaller gardens.Seed production in cultivation isrelatively low, but this species canalso be propagated by softwoodcuttings.Cultivars of F. majorF. major ‘Arkansas Beauty’ wasintroduced from a disjunct Arkansaspopulation growing in relativelydry habitat. Though durable it isa sparse bloomer with inferiorautumn colour.F. major Mystic Harbor ‘KLMG’ is alarge shrub.14March 2008

ThePlantsman<strong>Rick</strong> <strong>Darke</strong><strong>Fothergilla</strong> major (left), F. x intermedia (centre) and F. gardenii (right). The intermediate nature of the hybrid means that garden plants can be difficult to identify<strong>Fothergilla</strong> x intermediaThe recent horticultural renaissanceof <strong>Fothergilla</strong> can be traced to lines ofcompact plants that began appearingwithin the US nursery scene in thelate 1970s and early 1980s. Grownfrom open-pollinated seed obtainedfrom nursery plants of F. major andF. gardenii growing in proximity toone another, the seedlings wereselected for compact size, vigour,prolific bloom and good autumncolour. Some growers continuedthe lines through cutting propagationand others sold select seedlings, butmost of these plants were offeredsimply as F. gardenii and called dwarffothergilla. This identity was notquestioned at the time but the plantswere clearly intermediate in anumber of traits.The new plants filled a nichepreviously unoccupied by <strong>Fothergilla</strong>.Typically under 1.5m tall even after anumber of years growth, theircompact size was ideally suited forsmall residential gardens. Theiradaptability to a wide range of soiland moisture conditions meant theycould be planted without great carein a variety of garden settings andstill remain healthy and attractive.The were even durable enough to beused in sweeps, masses, and forhedging and enclosure, and vigorousenough to withstand aggressivepruning or periodic shearing to theground when design imperativesdictated even lower height. Theywere truly, reliably, four-seasonshrubs offering fragrant springflowers, neatly attractive summerfoliage, unsurpassed autumn colour,and pleasing winter architecture.The availability of these newfothergillas coincided with theincreasing momentum of the nativeplant movement in the US, whichencouraged gardeners and landscapearchitects to redirect their focus tothe diversity of the North Americanflora. Although this flora is rich withshrubby species, few rival the allaroundutility of the best fothergillas.Another turning point was MichaelDirr’s introduction of <strong>Fothergilla</strong>‘Mount Airy’. Here at last was anamed cultivar with the mostdesirable characters of the newcompact types. Selected by Dirr➤March 2008 15

GENUS PROFILEfrom a plant growing at Mount AiryArboretum in Cincinnati, Ohio,‘Mount Airy’ possessed anadditional, fundamentally importanttrait: it was especially amenable tocuttings propagation, providing thenursery industry with a supremelymarketable shrub that could beproduced economically in largequantities and that presented itselfwell as a young container plant.<strong>Fothergilla</strong> ‘Mount Airy’ wasvariously offered as F. gardenii andF. major, adding to the growing debateabout whether these intermediateplants might be hybrids.Decades earlier, Richard Weaverhad determined that F. gardenii was atetraploid (with 48 chromosomes)and F. major was a hexaploid (with72 chromosomes) (Weaver 1969).He brought this up in conversationwith Tom Ranney at North CarolinaState University’s MountainHorticultural Crops Research andExtension Center a few years agoand Ranney subsequently launcheda study to settle the debate. Workingwith Nathan Lynch, Paul Fantz,Paul Cappiello and other staff atthe Center, the University, andYew Dell Gardens, Ranney usedflow cytometry to determine ploidylevels (chromosome number) of17 different cultivated taxa of<strong>Fothergilla</strong>. Flow cytometry is amethod of sorting cells in a streamof fluid that allows ploidy level tobe determined.The results of this study (Ranneyet al. 2007) are both profoundlyilluminating and somewhat unsurprising:the majority of commerciallyavailable cultivars are pentaploids:hybrids with 60 chromosomes. Inthe same article, the new hybridspecies F. x intermedia is named anddescribed. This name can now beadopted for hybrid fothergillas.Though individual testing would berequired for absolute proof, it is<strong>Rick</strong> <strong>Darke</strong><strong>Rick</strong> <strong>Darke</strong>The inflorescences of <strong>Fothergilla</strong> x intermedia (top); in both species and the hybrid they are fragrant,appear in late spring and are composed mainly of stamens. The intensely glaucous leaves ofF. x intermedia ‘Blue Shadow’ (above) will further excite renewed interest in the genus16March 2008

ThePlantsmanreasonable to assume that a highpercentage of intermediate plantsoffered commercially in recentdecades as F. gardenii are actuallyF. x intermedia. The cultivars in thisarticle are grouped according to theconclusions of Ranney et al. (2007).Cultivars of F. x intermediaF. x intermedia Beaver Creek(‘KLMtwo’). Raised by plantbreeder Roy Klehm, this cultivar iscompact and rounded in form,remaining under 1.2m in height aftera decade of growth. Its blue-greensummer foliage turns bright yellowto red in autumn.F. x intermedia ‘Blue Shadow’ iswithout question the most dramaticnew <strong>Fothergilla</strong> and perhaps one ofthe most promising new shrubs yetto appear in the current century.Introduced and patented in the USby Gary Handy of Handy Nurseryin Oregon, it originated as a branchsport from ‘Mount Airy’. It is similarto ‘Mount Airy’ in most characteristicsexcept the leaves, which emergegreen, quickly maturing to an intensepowder blue that almost has to beseen to be believed. The colour rivalsthat of other glaucous plants such asZenobia pulverulenta and even Senecioserpens. Although relatively easy toroot from cuttings, this plant has alsobeen tissue-cultured to meet demandmore quickly.F. x intermedia Eastern form wasintroduced to cultivation years agoas F. gardenii. It is an unremarkableexample of the hybrid.F. x intermedia May Bouquet(‘KLMsixteen’). Roy Klehmselected this hybrid primarily for itsunusually abundant 5cm-tall flowerspikes. Autumn colour is typicallyclear yellow to apricot.F. x intermedia ‘Mount Airy’ is abenchmark against which otherintermediate hybrids are judged.Introduced by Michael Dirr froma plant growing at Mount AiryArboretum in Ohio, it is rounded inform, growing 1.8m tall at maturity,with abundant fragrant flowers, deepblue-green summer foliage andconsistently vibrant red or orangeredautumn colour. Although manyunnamed intermediate hybrids incommerce match it in ornamentalcharacters, ‘Mount Airy’ is a certainperformer and one of the easiest topropagate. Paul Cappiello hasobserved that this plant is so easilyrooted in the southeastern US, thewindow for taking cuttings extendsfrom May into September.F. x intermedia ‘Red Licorice’ isrelatively small-leaved and lowgrowing.Selected for its dark redautumn colour, it was introducedfrom Kentucky’s BernheimArboretum by Paul Cappielloand John Wachter.F. x intermedia Red Monarch(‘KLMfifteen’). Growing 2.4m tallat maturity, this Roy Klehm introductionis larger than many of thehybrids, with reliable deep orangeredautumn colour.F. x intermedia ‘Sea Spray’ reaches1.5m or more at maturity, and hassummer foliage that is more bluegreenthan average. The autumncolour is muted.F. x intermedia ‘Windy City’ is arecent midwestern US introductionwith green summer foliage and coldhardinessinto USDA zone 4.The future of <strong>Fothergilla</strong>The diversity and durability ofmaterial now available will ensure<strong>Fothergilla</strong> never again recedes intoACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThanks to Paul Cappiello, Mike Dirr,Gary Handy, Roy Klehm, <strong>Rick</strong>Lewandowski, Dick Lighty, Bob Peet,Tom Ranney, Bruce Sorrie and DickWeaver for generously sharing theirknowledge and insights on <strong>Fothergilla</strong>obscurity. The broad appeal andutility of the hybrids will continue toelevate this distinctive genus in theworld rank of ornamental shrubs. Itis hoped that continued developmentof this genus will result in an evengreater range of unique and provenselections.Further introduction of plantswith known provenance, and abetter understanding of the ecologicalcontext of the species, will contributeto their more effective cultivationand to the roles they will playin designed spaces and conservedplaces.RICK DARKE, previously Curator atLongwood Gardens, Pennsylvania,is an author, photographer, andlandscape consultant.www.rickdarke.comREFERENCESBean, WJ (1988) Trees and ShrubsHardy in the British Isles. 8th edition.John Murray, LondonRanney, TG, Lynch, NP, Fantz, PR& Cappiello, C (2007) Clarifyingtaxonomy and nomenclature of<strong>Fothergilla</strong> (Hamamelidaceae) cultivarsand hybrids. HortScience 42(3):470–473Sargent, CS (1895) New or littleknownplants. <strong>Fothergilla</strong> gardenii.Gard. & Forest 9(402): 445–446Sorrie, BA, Gray, JB, Crutchfield,PJ (2006) The vascular flora of thelongleaf pine ecosystem of Fort Braggand Weymouth Woods, NorthCarolina. Castanea 71(2): 129–161Weakley, AS (2007) Flora of theCarolinas, Virginia, Georgia, andSurrounding Areas. University ofNorth Carolina Herbarium, ChapelHill, NC. (working draft of 11 Jan2007, www.herbarium.unc.edu/flora.htm )Weaver, Jr, RE (1969) Studies in theNorth American genus <strong>Fothergilla</strong>(Hamamelidaceae). J. Arnold Arbor.50(4): 599–619Weaver, Jr, RE (1971) Thefothergillas. Arnoldia 31(3): 89–97March 2008 17