The Magazine of the Arnold Arboretum - Arnoldia - Harvard University

The Magazine of the Arnold Arboretum - Arnoldia - Harvard University

The Magazine of the Arnold Arboretum - Arnoldia - Harvard University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

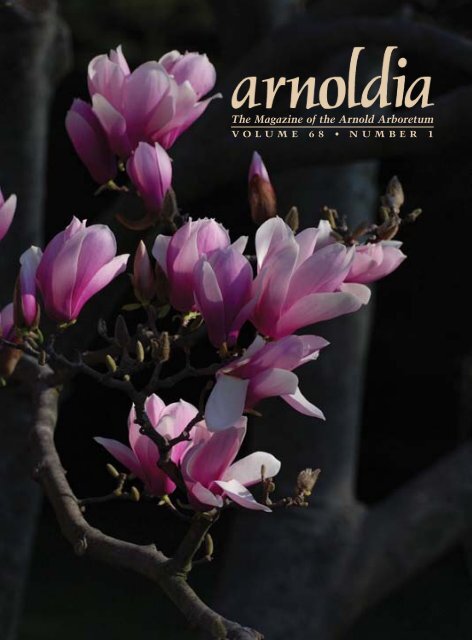

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

V O L U M E 6 8 • N U M B E R 1

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

VOLUM E 68 • N UM BER 1 • 2010<br />

Contents<br />

<strong>Arnold</strong>ia (ISSN 0004–2633; USPS 866–100)<br />

is published quarterly by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>University</strong>. Periodicals postage paid<br />

at Boston, Massachusetts.<br />

Subscriptions are $20.00 per calendar year<br />

domestic, $25.00 foreign, payable in advance.<br />

Remittances may be made in U.S. dollars, by<br />

check drawn on a U.S. bank; by international<br />

money order; or by Visa, Mastercard, or American<br />

Express. Send orders, remittances, requests to<br />

purchase back issues, change-<strong>of</strong>-address notices,<br />

and all o<strong>the</strong>r subscription-related communications<br />

to Circulation Manager, <strong>Arnold</strong>ia, <strong>Arnold</strong><br />

<strong>Arboretum</strong>, 125 Arborway, Boston, MA 02130-<br />

3500. Telephone 617.524.1718; fax 617.524.1418;<br />

e-mail arnoldia@arnarb.harvard.edu<br />

<strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> members receive a subscription<br />

to <strong>Arnold</strong>ia as a membership benefit. To<br />

become a member or receive more information,<br />

please call Wendy Krauss at 617.384.5766 or<br />

email wendy_krauss@harvard.edu<br />

Postmaster: Send address changes to<br />

<strong>Arnold</strong>ia Circulation Manager<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

125 Arborway<br />

Boston, MA 02130–3500<br />

Nancy Rose, Editor<br />

Andy Win<strong>the</strong>r, Designer<br />

Editorial Committee<br />

Phyllis Andersen<br />

Peter Del Tredici<br />

Michael S. Dosmann<br />

Kanchi N. Gandhi<br />

2 Magnolias at <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Swarthmore College<br />

Andrew Bunting<br />

13 Excerpts from Wild Urban Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>ast: A Field Guide<br />

Peter Del Tredici<br />

26 Conserving <strong>the</strong> Dawn Redwood: <strong>The</strong> Ex Situ<br />

Collection at <strong>the</strong> Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

Greg Payton<br />

34 Index to <strong>Arnold</strong>ia Volume 67<br />

44 A New Plant Introduction from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong><br />

<strong>Arboretum</strong>: Ilex glabra ‘Peggy’s Cove’<br />

John H. Alexander III<br />

Front cover: ‘Verbanica’, a cultivar <strong>of</strong> saucer magnolia<br />

(Magnolia x soulangiana), was introduced in France in<br />

1873. Photo by Nancy Rose.<br />

Inside front cover: Urban wildflower or wicked weed?<br />

A new field guide, Wild Urban Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast,<br />

doesn’t judge, but will aid city dwellers in identifying<br />

<strong>the</strong> plants around <strong>the</strong>m. Photo <strong>of</strong> hedge bindweed<br />

(Calystegia sepium) by Peter Del Tredici.<br />

Inside back cover: Plant propagator John H. Alexander III<br />

stands behind <strong>the</strong> original plant <strong>of</strong> Ilex glabra ‘Peggy’s<br />

Cove’, a new inkberry cultivar. Photo by Oren McBee.<br />

Back cover: Dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides)<br />

has a storied history but continues to face<br />

conservation challenges. This unusual multi-trunked<br />

specimen is from a 1948 seed accession at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong><br />

<strong>Arboretum</strong>. Photo by Michael Dosmann.<br />

Copyright © 2010. <strong>The</strong> President and<br />

Fellows <strong>of</strong> <strong>Harvard</strong> College

Magnolias at <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> Swarthmore College<br />

Andrew Bunting<br />

From <strong>the</strong> inception in 1929 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scott<br />

<strong>Arboretum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Swarthmore College, <strong>the</strong><br />

mission has remained <strong>the</strong> same—to collect<br />

and display outstanding ornamental plants,<br />

specifically trees, shrubs, and vines. Since<br />

1931, one <strong>of</strong> our most prominent collections<br />

<strong>of</strong> plants—and one that has stood <strong>the</strong> test <strong>of</strong><br />

time—has been <strong>the</strong> magnolia collection. Early<br />

on, new magnolia accessions were received from<br />

notable nurseries, organizations, and individuals<br />

including Bobbink and Atkins, Ru<strong>the</strong>rford,<br />

New Jersey; Andorra Nursery, Chestnut Hill,<br />

Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

Part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> magnolia collection at <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>.

Magnolias at <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> 3<br />

Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> original type specimen <strong>of</strong> Magnolia virginiana<br />

var. australis ‘Henry Hicks’ still thrives at <strong>the</strong> Scott<br />

<strong>Arboretum</strong> (above). This cultivar bears fragrant, creamy<br />

white flowers and cold-hardy evergreen foliage (right).<br />

Pennsylvania; <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong>; Hicks<br />

Nursery, Long Island, New York; and Highland<br />

Park, Rochester, New York.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> time, John Wister, first director <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>, was developing <strong>the</strong><br />

campus based on an evolutionary or phylogenetic<br />

tree, so all genera in a plant family were<br />

planted toge<strong>the</strong>r, and hence all species in a family<br />

resided toge<strong>the</strong>r. <strong>The</strong> magnolia collection<br />

housed both species and cultivars alike.<br />

In 1931, Wister began to get regular deliveries<br />

<strong>of</strong> many plants, especially magnolias, from<br />

Henry Hicks <strong>of</strong> Hicks Nursery on Long Island,<br />

New York. On May 8th, 1934, Hicks brought<br />

Wister a gift <strong>of</strong> plants which included 61 accessions<br />

representing 3,143 individual plants.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se included seven seedlings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sweetbay<br />

magnolia (Magnolia viginiana), a native species<br />

which was <strong>the</strong>n known as Magnolia glauca. Of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se original seven, only one survived. It was<br />

Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>

4 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1<br />

Early History <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

In 1929, John Caspar Wister was appointed <strong>the</strong> first director <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arthur Hoyt<br />

Scott Horticultural Foundation (now <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>). Wister graduated<br />

in 1909 with a degree from <strong>the</strong> School <strong>of</strong> Landscape Architecture at <strong>Harvard</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong>, and supplemented this education with courses taken at <strong>the</strong> New<br />

Jersey Agricultural College. After graduation, Wister worked in landscape architecture<br />

<strong>of</strong>fices in both Philadelphia and New York.<br />

From his youth, John Wister was an avid plant collector. As a small boy he had<br />

exposure to estate gardening at different Wister properties located in and around<br />

Germantown, Philadelphia. At age 14 he grew 40 cultivars <strong>of</strong> chrysan<strong>the</strong>mums.<br />

After Wister started his pr<strong>of</strong>essional career his interest in a myriad <strong>of</strong> plant groups<br />

and genera began to grow. Throughout his lifetime he was an avid collector <strong>of</strong> both<br />

herbaceous and tree peonies. Wister admired a photograph in a garden catalog that<br />

showed <strong>the</strong> peony collection <strong>of</strong> Arthur Hoyt Scott (for whom <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> is<br />

named) and Edith Wilder Scott and in 1913 he met <strong>the</strong> Scotts at <strong>the</strong>ir home in<br />

Oak Lane, Philadelphia.<br />

On July 10, 1917, at <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> 30, Wister enlisted as a private in World War I.<br />

Wister was sent to France. On his leave time during <strong>the</strong> war Wister toured<br />

<strong>the</strong> gardens <strong>of</strong> Europe. While in France he collected several cultivars <strong>of</strong> tree<br />

peonies and sent <strong>the</strong> plants back to Mr. and Mrs. Scott. Wister was honorably<br />

discharged in 1919.<br />

Arthur Hoyt Scott was a graduate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> class <strong>of</strong> 1895 from Swarthmore<br />

College. His fa<strong>the</strong>r, E. Irvin Scott, founded Scott Paper Company which was<br />

located in Chester, just south <strong>of</strong> Swarthmore, Pennsylvania. Like Wister, Scott<br />

developed a passion for ornamental horticulture as a young man. In 1920 he<br />

became president <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scott Paper Company, but his spare time was primarily<br />

occupied by his love <strong>of</strong> plants. Scott served as an <strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American Peony<br />

Society and <strong>the</strong> American Iris Society. As early as 1915 Scott was sending gifts<br />

<strong>of</strong> plants to his alma mater, Swarthmore College. His first gift was 100 lilacs <strong>of</strong><br />

many different varieties. In 1919 <strong>the</strong> Scotts moved from Philadelphia to a 100-acre<br />

farm in Rose Valley near Swarthmore. As Wister later wrote “Here for <strong>the</strong><br />

first time he had ample room. He at once began to plant great collections <strong>of</strong><br />

flowering trees and shrubs like Japanese cherries, crabapples, dogwoods, lilacs,<br />

mockoranges and azaleas.”<br />

When Arthur Hoyt Scott wanted to study peonies he had to travel to Cornell<br />

<strong>University</strong> and when he wanted to see lilacs he had to go to Highland Park in<br />

Rochester, New York. Scott dreamed <strong>of</strong> having an arboretum at Swarthmore<br />

College where local gardeners could go and see attractive displays <strong>of</strong> his favorite<br />

plants. Scott had <strong>the</strong> support <strong>of</strong> Samuel Palmer, <strong>the</strong> head <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Botany Department,<br />

and Swarthmore College. Palmer, in turn, contacted Robert Pyle who<br />

had graduated from Swarthmore in 1897 and was serving on Swarthmore’s board<br />

<strong>of</strong> managers. Pyle was head <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Conard-Pyle Company, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country’s<br />

largest purveyors <strong>of</strong> mail-order roses.

Magnolias at <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> 5<br />

Archives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Swarthmore College<br />

John C. Wister (second from right) at <strong>the</strong> dedication <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>’s rose garden in 1958. Wister was director <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scott<br />

<strong>Arboretum</strong> from 1929 to 1969.<br />

Arthur Hoyt Scott died in 1927, at <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> 51. Two years later Edith Wilder<br />

Scott and Arthur Hoyt Scott’s sister, Margaret Moon, and her husband, Owen<br />

Moon, approached Swarthmore’s president with <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> starting a campus<br />

arboretum. <strong>The</strong>y recommended that John Wister become its first director, and<br />

so indeed he did.<br />

<strong>The</strong> early 1930s were <strong>the</strong> heydays <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scott Horticultural Foundation. With<br />

Wister at <strong>the</strong> helm, <strong>the</strong> plant collections grew very quickly. Huge collections <strong>of</strong><br />

Paeonia, Iris, Rhododendron, Syringa, Philadelphus, Prunus, Malus, Cotoneaster,<br />

Chrysan<strong>the</strong>mum, Narcissus and Magnolia were being accessioned and planted.<br />

In 1931 <strong>the</strong> Foundation accessioned 783 plants; in 1932 <strong>the</strong>re were 1162 accessions,<br />

and in 1933, 1110 accessions. To put this in perspective <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

currently accessions about 300 plants per year.

6 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1<br />

planted in a poorly drained section <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Magnolia Collection, and over <strong>the</strong> years this<br />

sweetbay magnolia thrived (unlike most magnolias,<br />

this species performs well in wet soils).<br />

It was observed that while most specimens <strong>of</strong><br />

Magnolia viriginiana in <strong>the</strong> Swarthmore area<br />

are deciduous, this particular specimen was<br />

reliably evergreen. In 1967 this clone was <strong>of</strong>ficially<br />

registered and named Magnolia virginiana<br />

var. australis ‘Henry Hicks’. <strong>The</strong> original<br />

type specimen remains in great shape today in<br />

<strong>the</strong> old Magnolia Collection.<br />

A Stream <strong>of</strong> Magnolias<br />

In addition to Magnolia virginiana, several<br />

accessions <strong>of</strong> Oyama magnolia (Magnolia<br />

sieboldii, previously M. parviflora), a shrubby<br />

Asian magnolia noted for its white flowers with<br />

striking crimson stamens, were added to <strong>the</strong><br />

collection from several different sources. O<strong>the</strong>r<br />

early additions included <strong>the</strong> star magnolia<br />

(Magnolia stellata), anise magnolia (Magnolia<br />

salicifolia), umbrella magnolia (Magnolia<br />

tripetala), Kobus magnolia (Magnolia kobus),<br />

sou<strong>the</strong>rn magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora),<br />

cucumbertree magnolia (Magnolia acuminata),<br />

and <strong>the</strong> saucer magnolia (M. x soulangiana, syn.<br />

Magnolia x soulangeana).<br />

Magnolia x soulangiana resulted from a cross<br />

between Magnolia denudata and Magnolia liliiflora<br />

in 1820 by Étienne Soulange-Bodin, who<br />

was <strong>the</strong> first director <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Royal Institute <strong>of</strong><br />

Horticulture near Paris. For many gardeners<br />

across <strong>the</strong> United States, saucer magnolia is<br />

<strong>the</strong> quintessential magnolia species. This large<br />

shrub to medium-sized tree produces masses<br />

<strong>of</strong> large, showy flowers that emerge before <strong>the</strong><br />

foliage. <strong>The</strong> flowers, which are <strong>of</strong>ten fragrant,<br />

appear in white and shades <strong>of</strong> pink and purple.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> early 1930s <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

received two different batches <strong>of</strong> Magnolia x<br />

soulangiana cultivars. In 1933, Arthur D. Slavin<br />

at Highland Park in Rochester, New York, sent<br />

‘Alexandrina’, which has deep red-purple flowers<br />

and was introduced in Paris in 1831; ‘Amabilis’,<br />

an 1865 French introduction with white<br />

flowers; ‘Alba’, which is ano<strong>the</strong>r white-flowered<br />

clone that was grown and named by Louis<br />

van Houtte <strong>of</strong> Belgium; ‘André Leroy’, which<br />

has dark pink to purple flowers and is a French<br />

<strong>The</strong> slightly nodding flowers <strong>of</strong> Magnolia sieboldii bloom in<br />

late spring or early summer.<br />

Early-spring-flowering Magnolia salicifolia has fragrant,<br />

6-tepaled white flowers and a pyramidal growth habit.<br />

Nancy Rose<br />

Nancy Rose

Magnolias at <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> 7<br />

Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

Magnolia x soulangiana ‘Alexandrina’ is noted for its dramatic redpurple<br />

flowers.<br />

A David Leach hybrid <strong>of</strong> M. acuminata x M. denudata, ‘Ivory Chalice’<br />

bears large, pale yellow to cream colored flowers.<br />

introduction from 1892; ‘Brozzoni’, which<br />

bears white flowers with pink veins and<br />

was named in honor <strong>of</strong> Camillo Brozzoni<br />

in Brescia, Italy in 1873; ‘Lennei’, which<br />

has tepals that are magenta on <strong>the</strong> outside<br />

and white on <strong>the</strong> inside; ‘Norbertii’, a lateblooming<br />

cultivar with red-purple flowers;<br />

and ‘Verbanica’, which has deep pink<br />

flowers and was named by André Leroy in<br />

France in 1873. In 1936, scions <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong>se<br />

clones were sent to Verkades Nursery in<br />

Wayne, New Jersey. <strong>The</strong> magnolias were<br />

propagated <strong>the</strong>re, and duplicate plants were<br />

<strong>the</strong>n sent back to <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>.<br />

Today, many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se original cultivars<br />

from Highland Park are found in our collections.<br />

Noted magnolia expert Philippe<br />

de Spoelberch from <strong>Arboretum</strong> Wespelaar,<br />

Haacht-Wespelaar, Belgium, commented<br />

that <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>’s collection <strong>of</strong><br />

Magnolia x soulangiana cultivars is important<br />

because <strong>the</strong>y most likely represent<br />

clones which are true to name. De Spoelberch<br />

said that many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> original cultivars<br />

from France are much confused in <strong>the</strong><br />

nursery industry and that many cultivar<br />

names have been mistakenly attributed to<br />

<strong>the</strong> wrong cultivar.<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Belles and Little Girls<br />

In 1933, <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> received<br />

its first plant <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn magnolia<br />

(Magnolia grandiflora) as a gift from Edith<br />

Wilder Scott. This large magnolia, native<br />

to <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>astern United States, is prized<br />

for its lea<strong>the</strong>ry evergreen foliage and large,<br />

fragrant, creamy white flowers. Several<br />

cultivars <strong>of</strong> this species were soon added<br />

to <strong>the</strong> collection; in 1939, ‘Exoniensis’<br />

was received from Princeton Nursery, and<br />

in 1940 ‘Lanceolata’ arrived from Hillier<br />

and Sons in Winchester, England. Both <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se clonal names are synonymous with<br />

‘Exmouth’, which is a fastigiate cultivar. It<br />

was not until 28 years later, in 1968, that<br />

any additional selections <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

magnolia were added to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong>’s<br />

collections. ‘Edith Bogue’ was a selection<br />

that was made in 1961 for its ability to withstand<br />

very cold temperatures with minimal

8 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1<br />

Nancy Rose<br />

Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

Nancy Rose<br />

Three <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “Little Girl” magnolia hybrids, (clockwise<br />

from above) ‘Betty’, ‘Ann’, and ‘Judy’. This<br />

group <strong>of</strong> magnolias was bred at <strong>the</strong> United States<br />

National <strong>Arboretum</strong> and named for <strong>the</strong> wives,<br />

daughters, and secretaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> breeders.<br />

leaf burn. Our plant came from Kingsville Nursery<br />

in Kingsville, Maryland. Today, <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

several specimens <strong>of</strong> ‘Edith Bogue’ growing on<br />

<strong>the</strong> campus <strong>of</strong> Swarthmore College, as well as<br />

7 o<strong>the</strong>r M. grandiflora cultivars including both<br />

‘D. D. Blanchard’ and ‘Pocono’ which also have<br />

been selected for greater cold hardiness.<br />

In 1968 <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> also received<br />

an important collection <strong>of</strong> magnolias from <strong>the</strong><br />

United States National <strong>Arboretum</strong>. Commonly<br />

referred to as <strong>the</strong> Eight Little Girls, <strong>the</strong>se<br />

magnolias were <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> hybridizing work<br />

conducted at <strong>the</strong> USNA by research geneticist<br />

Dr. Francis deVos and horticulturist William<br />

Kosar. In 1955, deVos began breeding working<br />

using Magnolia liliiflora ‘Nigra’ and Magnolia<br />

stellata ‘Rosea’. ‘Nigra’ was used for its hardiness<br />

and late blooming, while ‘Rosea’ was used<br />

for its fragrance, prolific flowering, and mildew<br />

resistance. <strong>The</strong> results <strong>of</strong> this program resulted<br />

in <strong>the</strong> introduction <strong>of</strong> cultivars ‘Ann’, ‘Judy’,<br />

‘Randy’, and ‘Ricki’. In 1956, Kosar hybridized<br />

Magnolia stellata ‘Rosea’ and ‘Waterlily’ with<br />

Magnolia liliiflora ‘Nigra’ and ‘Reflorescens’,<br />

which resulted in <strong>the</strong> introduction <strong>of</strong> cultivars<br />

‘Betty’, ‘Jane’, ‘Pinkie’, and ‘Susan’. Today at

Magnolias at <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> 9<br />

Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

A specimen <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rare Florida native Magnolia macrophylla subsp. ashei growing at <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>.<br />

<strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> ‘Ann’, ‘Betty’, and ‘Susan’<br />

remain as beautiful mature specimens, while<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs that we lost have been replaced with<br />

younger specimens. <strong>The</strong> “Little Girl” hybrids<br />

remain a group <strong>of</strong> magnolias that we continue<br />

to promote as relatively small (about 12 to 20<br />

feet [3.5 to 6 meters] tall) magnolias for <strong>the</strong><br />

home garden.<br />

In addition to Magnolia virginiana and Magnolia<br />

grandiflora, <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> added<br />

several o<strong>the</strong>r magnolia species native to <strong>the</strong><br />

United States. We received <strong>the</strong> umbrella magnolia<br />

(Magnolia tripetala) from <strong>the</strong> Hicks Nursery<br />

in 1932 and Magnolia fraseri came from<br />

Arthur D. Slavin at Highland Park Nursery in<br />

1933. Magnolia macrophylla, which is closely<br />

related to Magnolia fraseri, was acquired from<br />

Andorra Nursery near Philadelphia in 1939.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>’s first plant <strong>of</strong> Magnolia<br />

pyramidata (which is sometimes listed as<br />

Magnolia fraseri subsp. pyramidata) came to us<br />

via <strong>the</strong> Henry Foundation for Botanical Research<br />

in Gladwyne, Pennsylvania in 1971. This species<br />

is native to <strong>the</strong> coastal plains <strong>of</strong> Alabama,<br />

Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, South<br />

Carolina, and Texas, while Magnolia fraseri is<br />

only found in <strong>the</strong> mountains. It wasn’t until<br />

1991 that we added <strong>the</strong> last <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> North American<br />

native magnolias, a single plant <strong>of</strong> Magnolia<br />

macrophylla subsp. ashei. Ashe’s magnolia<br />

is very rare in <strong>the</strong> wild and only occurs in a<br />

small portion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Florida panhandle where<br />

it is found from Leon to Wakulla counties and<br />

westward to Santa Rosa county. In <strong>the</strong> Red List<br />

<strong>of</strong> Magnoliaceae, which documents globally<br />

threatened plants within <strong>the</strong> magnolia family,<br />

Magnolia macrophylla subsp. ashei is given<br />

<strong>the</strong> conservation status <strong>of</strong> “vulnerable”, which<br />

means it is considered to be facing a high risk<br />

<strong>of</strong> extinction in <strong>the</strong> wild.

10 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1<br />

Courtesy <strong>of</strong> PAT McCracken<br />

Nancy Rose<br />

‘Gold Crown’, an August Kehr hybrid, bears large, light to<br />

medium yellow flowers.<br />

Recent Additions, Future Plans<br />

<strong>The</strong> 1990s saw dozens <strong>of</strong> new cultivars enter<br />

<strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>’s collections from many<br />

magnolia purveyors such as Arbor Village<br />

Nursery, Gossler Farms, and Fairwea<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Gardens. In 1998, through Pat McCracken<br />

and McCracken Nursery, we received a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> cultivars introduced by noted magnolia<br />

hybridizer Dr. August Kehr. After retiring<br />

from <strong>the</strong> USDA, Kehr started a robust magnolia<br />

breeding program in Hendersonville, North<br />

Carolina that resulted in many outstanding<br />

cultivars <strong>of</strong> magnolias. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Kehr cultivars<br />

included in our magnolia collection are<br />

‘Serenade’, ‘Pink Perfection’, and a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> much-desired yellow-flowered hybrids<br />

including ‘Gold Crown’, ‘Golden Endeavor’,<br />

Magnolia zenii is a critically endangered species in its native<br />

range in China.<br />

‘Hot Flash’, ‘Solar Flair’, and ‘Sunburst’. To<br />

create <strong>the</strong> yellow magnolias Kehr made complex<br />

crosses using M. acuminata, M. denudata,<br />

M. x brooklynensis, M. ‘Elizabeth’, M.<br />

‘Woodsman’ and M. ‘Gold Star’.<br />

From 2000 to 2010 <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> continued<br />

to add dozens <strong>of</strong> new magnolia taxa to<br />

our collection. Many new cultivars <strong>of</strong> Magnolia<br />

grandiflora and Magnolia virginiana were<br />

added. Several o<strong>the</strong>r yellow-flowered magnolias<br />

such as ‘Yellow Joy’, ‘Limelight’ and ‘Golden<br />

Rain’ were added. In addition, many species<br />

magnolias from a variety <strong>of</strong> sources were accessioned,<br />

including Magnolia x wiesneri, a hybrid<br />

between M. sieboldii and M. obovata; Magnolia<br />

zenii which is critically endangered in China<br />

where only one population, comprised <strong>of</strong> 18

Magnolias at <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> 11<br />

Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

Magnolia denudata ‘Swarthmore Sentinel’ was selected and named for its distinctly upright habit.

12 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1<br />

individual trees, exists; and Magnolia wilsonii,<br />

which is endangered and only exists in scattered<br />

populations in Sichuan, nor<strong>the</strong>rn Yunnan, and<br />

Guizhou, China. Two o<strong>the</strong>r additions—Magnolia<br />

lotungensis from China and M. tamaulipana<br />

from nor<strong>the</strong>astern Mexico —may prove to be<br />

borderline hardy in Swarthmore (USDA zone 6,<br />

average annual minimum temperature -10°F to<br />

0°F [-23.3°C to -17.8°C]).<br />

In 2009 <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> introduced a new<br />

selection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Yulan magnolia, Magnolia<br />

denudata ‘Swarthmore Sentinel’. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

originally received a seedling from J. C.<br />

Raulston at North Carolina State <strong>University</strong>,<br />

who had received seeds from <strong>the</strong> Beijing Botanic<br />

Garden. From a seedling in 1993, <strong>the</strong> tree is over<br />

30 feet tall today. On several occasions visiting<br />

magnolia experts commented on how upright<br />

our particular clone was. <strong>The</strong>refore, we decided<br />

to name this selection ‘Swarthmore Sentinel’<br />

for its fastigiate habit.<br />

Over <strong>the</strong> last 81 years we have accessioned<br />

502 magnolias at <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>. Today<br />

<strong>the</strong> collection holds 165 different taxa. <strong>The</strong><br />

Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>’s collection is recognized as<br />

a national magnolia collection through <strong>the</strong><br />

American Public Garden Association’s North<br />

American Plant Collections Consortium<br />

(NAPCC). According to <strong>the</strong> APGA “<strong>The</strong> North<br />

American Plant Collections Consortium is<br />

a network <strong>of</strong> botanical gardens and arboreta<br />

working to coordinate a continent-wide<br />

approach to plant germplasm preservation, and<br />

to promote high standards <strong>of</strong> plant collections<br />

management.” <strong>The</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> will be<br />

working with approximately 20 o<strong>the</strong>r institutions<br />

across North America, including San<br />

Francisco Botanical Garden, Quarryhill Botanical<br />

Garden, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> British Columbia<br />

Botanical Garden, <strong>the</strong> Bartlett <strong>Arboretum</strong>, and<br />

Atlanta Botanical Garden to create a consortium<br />

<strong>of</strong> institutions to oversee <strong>the</strong> preservation<br />

and conservation <strong>of</strong> Magnoliaceae germplasm.<br />

This group will also be part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> NAPCC<br />

and administered through <strong>the</strong> APGA. Once<br />

formed, this Magnolia Curatorial Group will<br />

partner with <strong>the</strong> Magnolia Society International<br />

to target both wild species and cultivar<br />

groups which need to be preserved in botanic<br />

gardens and arboreta. <strong>The</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

Magnolia ‘Charles Coates’ is an unusual hybrid between<br />

M. sieboldii and M. tripetala.<br />

will also continue to grow its own collections.<br />

We currently have 72 magnolia taxa growing<br />

in a nursery, and once <strong>the</strong>se reach specimen<br />

size <strong>the</strong>y will be transplanted to garden sites<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> arboretum. In 2015 <strong>the</strong> Scott<br />

<strong>Arboretum</strong> plans to host <strong>the</strong> international<br />

meeting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Magnolia Society International.<br />

Bibliography<br />

Callaway, D.J. 1994. <strong>The</strong> World <strong>of</strong> Magnolias. Timber<br />

Press, Portland, Oregon.<br />

Gardiner, J. 2000. Magnolias: A Gardener’s Guide. Timber<br />

Press, Portland, Oregon.<br />

Liu, Y.H. 2004. Magnolias <strong>of</strong> China. Hong-Kong, Beijing<br />

Science & Technology Press.<br />

Treseder, N.G. 1978. Magnolias. Faber and Faber, Limited,<br />

London and Boston.<br />

Wister, J.C. Swarthmore Plant Notes 1930–1954, Volume<br />

1, Part 1. pp. 80–88.<br />

Yagoda, B. 2003. <strong>The</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Swarthmore<br />

College—<strong>The</strong> First 75 Years. <strong>The</strong> Donning<br />

Company Press.<br />

Andrew Bunting is Curator <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Swarthmore College in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania.<br />

Scott <strong>Arboretum</strong>

Excerpts from Wild Urban Plants <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast: A Field Guide<br />

Peter Del Tredici<br />

Editor’s Note:<br />

Ever wonder what kind <strong>of</strong><br />

tree that is, <strong>the</strong> one growing<br />

from a crack in <strong>the</strong> asphalt<br />

parking lot at work? Or what that<br />

tangled vine engulfing <strong>the</strong> slope by<br />

<strong>the</strong> subway station might be? Wild<br />

Urban Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast: A<br />

Field Guide, written by long-time<br />

<strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> researcher<br />

Peter Del Tredici, may have your<br />

answer. Del Tredici’s goal with<br />

this book is “to help <strong>the</strong> general<br />

reader identify plants growing<br />

spontaneously in <strong>the</strong> urban environment<br />

and to develop an appreciation<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> role <strong>the</strong>y play in<br />

making our cities more livable.”<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 222 plants featured<br />

in <strong>the</strong> book could be called weeds,<br />

and some are notoriously invasive.<br />

<strong>The</strong> author eschews <strong>the</strong>se<br />

labels, however, pointing out that<br />

in many urban/suburban areas <strong>the</strong><br />

environment has been so radically<br />

altered (think non-native fill soils,<br />

soil compaction and contamination,<br />

impermeable pavement, and<br />

pollution) that <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> any<br />

plants has benefits.<br />

This handy guide is organized by plant families and includes both woody and herbaceous<br />

plants. Numerous color photographs and extensive information is provided for each<br />

species, including place <strong>of</strong> origin, descriptions <strong>of</strong> vegetative, flower, and fruit characteristics,<br />

and habitat preference. Some fascinating details emerge from <strong>the</strong> “Cultural Significance”<br />

subsections—for example: “During World War II, <strong>the</strong> silky seed hairs [<strong>of</strong> common<br />

milkweed, Asclepias syriaca] were used as a substitute for kapok to fill “Mae West” life<br />

vests. Between 1943 and 1945, a million such flotation devices were filled with <strong>the</strong> floss<br />

from some 24 million pounds (11 million kilograms) <strong>of</strong> milkweed pods.”<br />

Following are half a dozen plant species featured in <strong>the</strong> book. Reprinted from: Peter<br />

Del Tredici, Wild Urban Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast: A Field Guide. Copyright © 2010 by<br />

Cornell <strong>University</strong>. Used by permission <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> publisher, Cornell <strong>University</strong> Press. 374<br />

pages. ISBN 978-0-8014-7458-3.

14 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1

Wild Urban Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast 15

16 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1

Wild Urban Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast 17

18 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1

Wild Urban Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast 19

20 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1

Wild Urban Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast 21

22 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1

Wild Urban Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast 23

24 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1

Wild Urban Plants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>ast 25

Conserving <strong>the</strong> Dawn Redwood:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Ex Situ Collection at <strong>the</strong> Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong><br />

Greg Payton<br />

Since 1990, <strong>the</strong> Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong> in Newark,<br />

Ohio, has undertaken a large scale<br />

ex situ conservation project with Metasequoia<br />

glyptostroboides, <strong>the</strong> dawn redwood.<br />

Ex situ conservation is defined as <strong>the</strong> conservation<br />

<strong>of</strong> genes or genotypes outside <strong>the</strong>ir environment<br />

<strong>of</strong> natural occurrence (China, in <strong>the</strong><br />

case <strong>of</strong> dawn redwood). <strong>The</strong>re are challenges<br />

and limits to ex situ conservation, but for some<br />

threatened or endangered plants and animals it<br />

is an essential component in efforts to keep <strong>the</strong><br />

species from extinction. For a long-term conservation<br />

project to be successful and sustainable,<br />

a large sampling <strong>of</strong> genetic material is desirable<br />

to maintain <strong>the</strong> existing and potential variation<br />

within a particular species. Many attempts at<br />

rescue efforts are done on a limited basis, and<br />

<strong>the</strong>y hold relatively small numbers <strong>of</strong> specimens<br />

due to insufficient space and budgetary<br />

limitations. Ideally, ex situ collections should<br />

have <strong>the</strong> capacity to grow <strong>the</strong> requisite number<br />

<strong>of</strong> individuals essential for preserving <strong>the</strong> base<br />

Nancy Rose<br />

Dawn redwoods develop distinctive buttressed trunks with age.

Dawn Redwood at <strong>the</strong> Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong> 27<br />

Greg PAYTON<br />

Greg PAYTON<br />

A specimen with good form and foliage qualities (accession<br />

D1993-0249.004).<br />

gene reserve with a goal <strong>of</strong> capturing as large<br />

<strong>of</strong> a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> genetic diversity within <strong>the</strong><br />

species as possible. Some species require relatively<br />

few individuals to capture that genetic<br />

range, while o<strong>the</strong>rs require much larger population<br />

sizes. Studies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> genetic variation<br />

within dawn redwood have been and still are<br />

being conducted. Early results indicate that<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is a fairly low genetic diversity, although<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is some differentiation within <strong>the</strong> native<br />

populations throughout <strong>the</strong> overall range <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> species.<br />

Ex situ conservation does have its limits, and<br />

ideally it should complement in situ protection<br />

in <strong>the</strong> natural environment. Preserving a<br />

native, wild population is <strong>the</strong> best option, and<br />

this should be <strong>the</strong> primary focus <strong>of</strong> any conservation<br />

program. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> particular problems<br />

with ex situ conservation lies in <strong>the</strong> inevitable<br />

environmental differences between <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong><br />

origin and <strong>the</strong> site <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ex situ collection. If<br />

Variations in foliage <strong>of</strong> trees in <strong>the</strong> Dawes plantation. All<br />

branchlets photographed on October 13, 2009.<br />

plants in <strong>the</strong> ex situ site are allowed to sexually<br />

reproduce, environmental conditions in<br />

this new setting favor <strong>the</strong> selection and survival<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> progeny best adapted to that site.<br />

Progeny that survive in <strong>the</strong> ex situ location<br />

may have different traits than progeny which<br />

would have survived in <strong>the</strong> original site. While<br />

this may have advantages from a horticultural<br />

standpoint (e.g. selection <strong>of</strong> plants with greater<br />

cold hardiness or better drought tolerance), it<br />

is a disadvantage for most conservation goals.<br />

Preserving <strong>the</strong> genetic diversity <strong>of</strong> a species ex<br />

situ may be best accomplished by maintaining<br />

clonal populations. However, seed banking <strong>of</strong><br />

species with orthodox seeds (seeds that survive<br />

drying or freezing) can also be important in<br />

securing a species for <strong>the</strong> future, and <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>the</strong><br />

advantage that seeds can be stored in a much<br />

smaller space than living plants. A combination<br />

<strong>of</strong> both seed banking and living plants <strong>of</strong>fers <strong>the</strong><br />

most opportunities for conservation research.

28 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1<br />

Meet Metasequoia glyptostroboides<br />

Dawn redwood (shui-shan in Chinese, meaning<br />

“water-fir”) is a deciduous conifer similar to bald<br />

cypress (Taxodium distichum). <strong>The</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t, distichous<br />

needles <strong>of</strong> dawn redwood are arranged<br />

oppositely, easily distinguishing it from bald<br />

cypress with its alternate needle arrangement.<br />

When dawn redwood—once thought to be<br />

extinct—was discovered still growing in southcentral<br />

China in a mild and wet climate, it was<br />

not believed that it would survive in <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States north <strong>of</strong> Georgia. <strong>The</strong> provenance testing<br />

done since Metasequoia seeds arrived in <strong>the</strong><br />

United States in 1948 shows that it can survive<br />

in USDA Hardiness Zones 5 to 8 (average<br />

annual minimum temperature -20 to 20°F<br />

[-28.8 to -6.7°C]) in areas with sufficient rainfall<br />

(or with supplemental watering). In its native<br />

Sichuan, China, <strong>the</strong> average rainfall is around<br />

40 inches (100 centimeters) per year but dawn<br />

redwood has survived in parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States with lesser amounts <strong>of</strong> rainfall.<br />

<strong>The</strong> typical form is a large tree, up to 150<br />

feet (45 meters) tall in <strong>the</strong> wild, pyramidal in<br />

youth, becoming more open-crowned with<br />

great age. <strong>The</strong> trunks on older specimens<br />

become strongly buttressed. It is fast growing<br />

when moisture is available and can add over<br />

3 feet (1 meter) <strong>of</strong> growth per year. It is heliophilic<br />

(requiring full sun), which has limited<br />

its use as a commercial timber tree since it<br />

does not grow well in competition.<br />

Many millions <strong>of</strong> dawn redwoods have now<br />

been planted throughout China, but <strong>the</strong> condition<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> native population has remained stagnant.<br />

<strong>The</strong> 2009 IUCN Red List <strong>of</strong> Threatened<br />

Species gives dawn redwood a status <strong>of</strong> critically<br />

endangered, saying that <strong>the</strong> few remaining trees<br />

have been protected but that <strong>the</strong> habitat has not<br />

been, and <strong>the</strong>re are poor prospects for natural<br />

regeneration. <strong>The</strong> valleys <strong>the</strong> tree prefers have<br />

been denuded <strong>of</strong> vegetation and mature trees<br />

are <strong>of</strong>ten limbed up—all <strong>the</strong> way to <strong>the</strong> top—for<br />

firewood. Seedling reproduction is unlikely in<br />

this altered environment. In <strong>the</strong> past, natural<br />

seeding was also hampered because <strong>the</strong> seeds<br />

were collected and sold by farmers for various<br />

uses such as timber plantations. This practice<br />

has become less common in recent years, since<br />

An example <strong>of</strong> a plant that exists<br />

only ex situ is Franklinia alatamaha,<br />

Franklin tree. It is believed to have<br />

been extirpated from its native range<br />

(Georgia, in <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>astern United<br />

States) by <strong>the</strong> early nineteenth century.<br />

Fortunately, botanists John and<br />

William Bartram found and later collected<br />

and propagated Franklin tree<br />

in <strong>the</strong> late eighteenth century, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> species still survives in cultivation<br />

today. It blooms from late summer into<br />

autumn, and flowering <strong>of</strong>ten overlaps<br />

with fall foliage color.<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r Chinese conifers have provided lumber <strong>of</strong><br />

greater quality. In addition, propagation from<br />

cuttings has proven to be advantageous for producing<br />

new plants.<br />

Recent surveys indicate that 5,396 native<br />

trees (<strong>of</strong> all ages) still remain in <strong>the</strong> native range<br />

in China. <strong>The</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> trees (5,363) grow<br />

in western Hubei, while 28 grow in eastern<br />

Chongqing. Only 5 trees remain in Hunan.<br />

Nancy Rose

Dawn Redwood at <strong>the</strong> Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong> 29<br />

A Case <strong>of</strong> Depression and <strong>the</strong><br />

“Single Tree” <strong>The</strong>ory<br />

In 1983, Dr. John Kuser, a forestry pr<strong>of</strong>essor at<br />

Rutgers <strong>University</strong>, surmised that cultivated<br />

Metasequoia in <strong>the</strong> United States were suffering<br />

from inbreeding depression. He said,<br />

“Apparently, variation in <strong>the</strong> amount <strong>of</strong><br />

genetic load carried by different trees causes<br />

some to be incapable <strong>of</strong> producing fertile selfpollinated<br />

seeds but allows o<strong>the</strong>rs to produce<br />

a few viable seeds and occasional trees to self<br />

quite well.” He noted that Metasequoia pollen<br />

is wingless and “tends to clump toge<strong>the</strong>r.” <strong>The</strong><br />

best seed germination was found to occur on<br />

trees that had been located advantageously for<br />

cross-pollination.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> time, <strong>the</strong> popular belief was that <strong>the</strong><br />

poor germination <strong>of</strong> seedlings was <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong><br />

trees in <strong>the</strong> United States having all originated<br />

from <strong>the</strong> single “type” tree in <strong>the</strong> village <strong>of</strong><br />

Maudao, China. However, allozyme variation<br />

work done in 1995 showed that <strong>the</strong> 1947 seeds<br />

were not likely to have come from a single isolated<br />

tree. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, a copy <strong>of</strong> a previously<br />

unpublished paper by W. C. Cheng dated March<br />

25, 1948 revealed, as stated above, that Hwa had<br />

found more than 1000 Metasequoia and about<br />

100 “big ones.” Apparently seeds from many<br />

Map by Greg PAYTON<br />

Map <strong>of</strong> native dawn redwood distribution and seedlot collection sites.

30 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1<br />

trees had been collected and disseminated. Poor<br />

seed set seems to stem from <strong>the</strong> fact that most<br />

seed production outside <strong>of</strong> China is <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong><br />

selfing (due to isolation <strong>of</strong> specimens).<br />

<strong>The</strong> genetic variation <strong>of</strong> dawn redwood in<br />

China was believed to be much greater than<br />

that in <strong>the</strong> United States, and in 1990 a cooperative<br />

research project on Metasequoia began<br />

between Dr. W. J. Libby at <strong>the</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

California, Berkeley, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Minghe Li at<br />

Huazhong Agricultural <strong>University</strong> in Hubei,<br />

China, and Dr. Kuser. A number <strong>of</strong> organizations<br />

contributed to fund <strong>the</strong> project, and it was<br />

at this point that <strong>the</strong> Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong> became<br />

involved in provenance testing <strong>of</strong> Metasequoia.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Li collected Metasequoia seeds from<br />

several locations in its native range in October<br />

1990. In April 1991, 53 packets <strong>of</strong> seeds were<br />

Greg PAYTON<br />

Photo by Burney Huff (Dawes archives)<br />

A dawn redwood specimen from <strong>the</strong> original 1949 seed accession<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong>. <strong>The</strong> photograph is from <strong>the</strong><br />

early 1990s when <strong>the</strong> tree was nearly 80 feet (24 meters) tall; a<br />

lightning strike later took out <strong>the</strong> top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tree.<br />

A bronze-foliaged specimen in <strong>the</strong> plantation (accession<br />

D1993-0237.005).<br />

received at Rutgers <strong>University</strong> from Pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

Li, 52 from trees that still had seed cones,<br />

and one packet <strong>of</strong> mixed seeds. <strong>The</strong>se seed lots<br />

were germinated, and only four <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> collections<br />

produced no seedlings. <strong>The</strong> remaining<br />

48 “families” were grown on, and complete<br />

collections were planned for both Rutgers and<br />

Dawes. <strong>The</strong> remaining seedlings were distributed<br />

to nearly 20 cooperating institutions and<br />

individuals in <strong>the</strong> United States and United<br />

Kingdom. (<strong>The</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> received<br />

125 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se seedlings.)<br />

In 1993 <strong>the</strong> Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong> received two<br />

shipments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dawn redwood seedlings from<br />

Rutgers. A total <strong>of</strong> 344 trees were planted in <strong>the</strong><br />

Dawes plantation. Because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> large size (8<br />

acres [3.2 hectares]) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dawes site we were<br />

able to plant <strong>the</strong> trees 25 feet (7.6 meters) apart<br />

so no subsequent thinning was necessary.<br />

Current Status <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dawes Collection<br />

<strong>The</strong> Dawes plantation <strong>of</strong> seedlings from Pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

Li and Rutgers currently consists <strong>of</strong> 320<br />

trees, which makes it one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> largest living<br />

ex situ conservation collections <strong>of</strong> documented<br />

wild-origin dawn redwood trees outside <strong>of</strong><br />

China. Through 2009, 24 trees have been lost

Dawn Redwood at <strong>the</strong> Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong> 31<br />

from this plantation, and one seed lot family<br />

has been lost completely from both <strong>the</strong> Dawes<br />

and Rutgers plantations. In 2009, Dawes began<br />

contacting o<strong>the</strong>r institutions to see what living<br />

accessions <strong>the</strong>y had from <strong>the</strong> original 52 seed<br />

lots; 29 new accessions (in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> vegetative<br />

cuttings) representing trees from seed lots<br />

where Dawes had few representatives were<br />

obtained from <strong>the</strong>se institutions. Since each<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se trees was originally grown from seeds,<br />

every tree is genetically unique and <strong>the</strong>refore<br />

valuable for its individuality. <strong>The</strong>se cuttings<br />

are currently doing well in propagation and will<br />

help to provide more genetic stock to add to <strong>the</strong><br />

diversity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation.<br />

<strong>The</strong> search for additional collections <strong>of</strong> this<br />

Li/Rutgers project is ongoing. Any o<strong>the</strong>r modern<br />

or historical collection <strong>of</strong> wild material<br />

would be invaluable to add to <strong>the</strong> Dawes collection.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> seed lots that had no germination<br />

was <strong>the</strong> only lot from Hunan, collected<br />

from three individual dawn redwoods <strong>the</strong>re, so<br />

we are especially interested in acquiring germplasm<br />

from <strong>the</strong> few trees in Hunan.<br />

In addition to <strong>the</strong> plantation trees, Dawes has<br />

a few o<strong>the</strong>r accessions <strong>of</strong> wild-collected Metasequoia:<br />

three accessions from <strong>the</strong> original 1947<br />

seedlings, received in 1950 from Ralph Chaney<br />

who presumably got his seeds from Merrill; a<br />

grove <strong>of</strong> 44 trees propagated by cuttings in 1960<br />

from <strong>the</strong> previous accession; and three individuals<br />

also propagated from <strong>the</strong> original accession.<br />

Into <strong>the</strong> Future<br />

In Metasequoia, female cones (macrosporangiate<br />

strobili) are typically produced when trees<br />

reach a height <strong>of</strong> 30 to 50 feet (9 to 15 meters<br />

). Male cones (microsporangiate strobili) are<br />

not produced until trees are 60 to 83 feet (18<br />

to 25 meters) in height. At this point, nei<strong>the</strong>r<br />

female nor male cones have been observed on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong> plantation trees.<br />

As <strong>the</strong> grove continues to grow and seed<br />

production begins, <strong>the</strong> resultant progeny will<br />

represent <strong>the</strong> greatest level <strong>of</strong> genetic variation<br />

within dawn redwood outside <strong>of</strong> China.<br />

<strong>The</strong> origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se plantation trees are from<br />

across <strong>the</strong> estimated 800 square kilometer (312<br />

sq. mi.) native range in central China where<br />

full cross-pollination is very unlikely. Studies<br />

have shown that trees in <strong>the</strong> native populations<br />

show a lack <strong>of</strong> spatial genetic flow, indicating<br />

Greg PAYTON<br />

Wide spacing allows ample room for trees in <strong>the</strong> dawn redwood plantation.

32 <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 68/1<br />

David Brandenburg<br />

<strong>The</strong> author with a witches’-broom on one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dawes plantation trees.<br />

In 2009, both <strong>the</strong> genetic and taxonomic (cultivar) collections <strong>of</strong> dawn redwoods at <strong>the</strong><br />

Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong> were granted full status as a North American Plant Collections Consortium<br />

(NAPCC) collection. This symbolizes <strong>the</strong> commitment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> staff and organization<br />

to fulfilling <strong>the</strong> duty <strong>of</strong> preserving this important collection. As a repository for North<br />

America, requests for propagation material are honored for research purposes.<br />

Of horticultural interest, <strong>the</strong>re are well over two dozen cultivars <strong>of</strong> Metasequoia that<br />

add to <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> variation within <strong>the</strong> species. ‘Miss Grace’ and ‘Bonsai’ are dwarf selections,<br />

‘Jack Frost’ has a hint <strong>of</strong> variegation, and ‘Ogon’ (syn. ‘Gold Rush’) is a Japanese<br />

cultivar with bright yellow foliage that originated from irradiated seeds. Several cultivar<br />

selections could be made from <strong>the</strong> Dawes plantation trees, as <strong>the</strong>re are some interesting<br />

habits and foliage types. Tree heights <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plantation trees are from scarcely 3 feet (1<br />

meter) tall to over 33 feet (10 meters), and habits range from squat and round to tall and<br />

narrow with many forms in between. Foliage varies from large and coarse to small and<br />

fine, with colors in shades <strong>of</strong> green and bronze. A witches’-broom—which may yield dwarf<br />

forms—has even been found on one specimen.

Dawn Redwood at <strong>the</strong> Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong> 33<br />

genetic isolation due to habitat fragmentation<br />

(Leng et al. 2007). As stated earlier, natural<br />

pollen dissemination is limited.<br />

Since <strong>the</strong>se wide-ranging Chinese collections<br />

are located toge<strong>the</strong>r in a single plantation<br />

at Dawes, broad genetic combinations could<br />

occur. <strong>The</strong> resultant mixed, open-pollinated<br />

seeds could prove useful for horticultural purposes<br />

as well as for selecting for resistance to<br />

any future insect or disease pressures. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

seeds would have limited use for some conservation<br />

projects (since <strong>the</strong>y are from mixed<br />

meta-populations), but <strong>the</strong>re is potential for<br />

controlled crossing within <strong>the</strong> separate seed<br />

lot collections, which would give greater conservation<br />

value. <strong>The</strong> seeds produced here will<br />

be made available to seed banks, researchers,<br />

and growers.<br />

This collection holds many opportunities<br />

for future studies and research to be conducted<br />

without traveling to China. <strong>The</strong> sister<br />

population at Rutgers <strong>University</strong> is currently<br />

<strong>the</strong> subject <strong>of</strong> an amplified fragment length<br />

polymorphism (AFLP) analysis to assess <strong>the</strong><br />

breadth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> genetic diversity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> collection.<br />

Since most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> genotypes at Rutgers<br />

are duplicates <strong>of</strong> dawn redwoods in <strong>the</strong> collection<br />

at Dawes, <strong>the</strong> data from <strong>the</strong> AFLP study<br />

will pertain to this collection as well. We hope<br />

that this successful ex situ collection at <strong>the</strong><br />

Dawes <strong>Arboretum</strong> will aid in <strong>the</strong> conservation<br />

and fur<strong>the</strong>r understanding <strong>of</strong> this ancient and<br />

impressive species.<br />

Bibliography<br />

Andrews, H.N. 1948. Metasequoia and <strong>the</strong> Living Fossils.<br />

Missouri Botanical Garden Bulletin 36(5):<br />

79–85.<br />

Bartholomew, B., D.E. Boufford, and S.A. Spongberg, 1983.<br />

Metasequoia glyptostroboides—Its Present<br />

Status in Central China. Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong><br />

<strong>Arboretum</strong> 64: 105–128.<br />

Ecker, Eisenman, S.W. 2009. Pers. comm. Rutgers<br />

<strong>University</strong>, School <strong>of</strong> Environmental and<br />

Biological Sciences, Department <strong>of</strong> Plant<br />

Biology and Pathology.<br />

GSPC. 2002. Global Strategy for Plant Conservation.<br />

Montreal: Secretariat <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Convention on<br />

Biological Diversity.<br />

Hendricks, D.R. 1995. Metasequoia Depression, Sex, and<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r Useful Information. Landscape Plant<br />

News 6(2): 7–10.<br />

Hendricks, D. and P. Sondergaard. 1998. Metasequoia<br />

glyptostroboides—50 years out <strong>of</strong> China.<br />

Observations from <strong>the</strong> United States and<br />

Denmark. Dansk Dendrologisk Arsskrift 6:<br />

6–24.<br />

Hsueh, C.-J. 1985. Reminiscences <strong>of</strong> Collecting <strong>the</strong> Type<br />

Specimens <strong>of</strong> Metasequoia glyptostroboides.<br />

<strong>Arnold</strong>ia 45(4): 10–18.<br />

Hu, H.H. 1948. How Metasequoia, <strong>the</strong> “living fossil” was<br />

discovered in China. Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> New York<br />

Botanical Garden 49(585): 201–207.<br />

IUCN. IUCN Red List <strong>of</strong> Threatened Species. Version<br />

2009.1. Retrieved October 12, 2009, from www.<br />

iucnredlist.org<br />

Kuser, J.E., D.L.Sheely, and D.R. Hendricks. 1997. Genetic<br />

Variation in Two ex situ Collections <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rare<br />

Metasequoia glyptostroboides (Cupressaceae).<br />

Silvae Genetica 46(5): 258–264.<br />

Kuser, J. 1983. Inbreeding Depression in Metasequoia.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong> 64: 475–481.<br />

Leng, Q. et.al. 2007. Database <strong>of</strong> Native Metasequoia<br />

glyptostroboides Trees in China Based on New<br />

Census Surveys and Expeditions. Bulletin <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Peabody Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History 48(2):<br />

185–233.<br />

LePage, B.A., C.J. Williams, and H. Yang. 2005. <strong>The</strong><br />

Geobiology and Ecology <strong>of</strong> Metasequoia.<br />

Springer.<br />

Li, M. 2009, November 1. Pers. comm.<br />

Li, X.-D., H.-W. Huang, and J.-Q. Li. 2003. Genetic<br />

diversity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> relict plant Metasequoia<br />

glyptostroboides. Biodiversity Science 11:<br />

100–108.<br />

Ma, J. 2003. On <strong>the</strong> unsolved mystery <strong>of</strong> Metasequioa.<br />

Acta Botanica Yunnanica (25)2: 155–172.<br />

Ma, J. 2003. <strong>The</strong> Chronology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “Living Fossil”<br />

Metasequoia glyptostroboides (Taxodiaceae): A<br />

Review (1943–2003). <strong>Harvard</strong> Papers in Botany<br />

8(1): 9–18.<br />

Ma, J. 2002. <strong>The</strong> History <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Discovery and Initial<br />

Seed Dissemination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Metasequoia<br />

glyptostroboides, A “Living Fossil”. Aliso 21(2):<br />

65–75.<br />

Ma, J. and G. Shao. 2003. Rediscovery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “first<br />

collection” <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘Living Fossil’, Metasequoia<br />

glyptostroboides. Taxon 52(3): 585–588.<br />

Merrill, E.D. 1998–1999. Ano<strong>the</strong>r Living Fossil Comes<br />

to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong>. <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 58–59(4-1):<br />

17–19.<br />

Sand, S. 1992. <strong>The</strong> Dawn Redwood. American<br />

Horticulturist 71(10): 40–44.<br />

Wyman, D. 1968. Metasequoia After Twenty Years in<br />

Cultivation. <strong>Arnold</strong>ia 28(10–11): 113–122.<br />

Greg Payton is <strong>the</strong> Plant Records Specialist at <strong>the</strong> Dawes<br />

<strong>Arboretum</strong> in Newark, Ohio.

Index to <strong>Arnold</strong>ia Volume 67<br />

Items in boldface refer to illustrations<br />

A<br />

Abies spp., and exotic beetles 1: 33, 35<br />

— homolepis, lightning-damaged 4:<br />

22, 22<br />

Abscisic acid 4: 15, 18–19<br />

— — photosyn<strong>the</strong>sis and 4: 19<br />

Acai juice 3: 23<br />

Acer spp., and exotic beetles 1: 35<br />

— davidii, in China 2: 22, 26<br />

— — bark 2: inside front cover<br />

— rubrum ‘Schlesingeri’ 2: 32, inside<br />

back cover<br />

— — — propagation and redistribution<br />

<strong>of</strong> 2: 32<br />

— saccharum 3: 31<br />

— sutchuenense, in China 2: 27<br />

Ackerman, Dr. William 1: 24, 28<br />

Acorns, features <strong>of</strong> 4: 2–5, 3–5, 10, 11<br />

Adenorachis 3: 21<br />

Aerial photography and mapping 1:<br />

10–19, 11–15, 17–19<br />

Aesculus spp., and exotic beetles 1:<br />

34, 35<br />

Afghanistan, pine from 3: 36, inside<br />

back cover<br />

Africa, pest beetles from 1: 33<br />

Agrilus planipennis 1: 34, 34<br />

Agr<strong>of</strong>orestry 3: 26–27<br />

Aiello, Anthony S., “Seeking Cold-<br />

Hardy Camellias” 1: 20–30<br />

Ailuropoda melanoleuca, discovery<br />

<strong>of</strong> 2: 23<br />

Akebia trifoliata, in China 2: 26<br />

Alders, as beetle host 1: 35<br />

Alexander, John H., III<br />

— — — — photographs by 1: inside<br />

front/back covers; 2: 18<br />

Allium tricoccum 3: 30<br />

Alnus spp., and exotic beetles 1: 35<br />

Alpha-pinene 1: 32<br />

Alpine plants, in China 3: 2–13, 4, 6,<br />

10–11<br />

Ambrosiella fungi 1: 35<br />

American ginseng 3: 28–30, 29–30, 35<br />

Amplified fragment length polymorphism<br />

(AFLP) 4: 7, 9–10<br />

Animal and Plant Health Inspection<br />

Service (APHIS), and beetles 1:<br />

31–35<br />

Anoplophora glabripennis 1: 34, 34<br />

Anteater 2: 30<br />

Anthocyanins 3: 23<br />

Anticancer plants 3: 23, 25<br />

Antioxidant fruit 3: 14–25<br />

— — commercial potential <strong>of</strong> 3: 23–25<br />

Ants, leaf-cutter 2: 30<br />

Appalachian Mts., Tennessee 3: 20<br />

Apple, original 2: 20<br />

— fruiting genotypes 2: 20<br />

— quince and 1: 3<br />

— scab resistance 2: 10, 10, 20<br />

Apple-pear, Asian 4: 28<br />

Apomixis 3: 19, 21, 22, 24–25<br />

Arboriculture and plant hormones 4:<br />

15–19<br />

Arborvitae, as beetle host 1: 35<br />

Arisaema dilatatum, in China 2:<br />

27, 28<br />

Armenia, quince-growing in 1: 5, 5<br />

<strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong>, Acer rubrum<br />

‘Schlesingeri’ at 2: 32, inside back<br />

cover<br />

— — aerial photographs <strong>of</strong> 1: 1927,<br />

11; 1929, 13; 1936, 14; 1955, 13,<br />

18; 1967, 12; 1968, 15; 2005, front<br />

cover, 11, 15; 2006, 18; 2007, 12;<br />

2008, 17; 2009, 19; 2: 2008, 14<br />

— — apple selection at 2: 20<br />

— — autumn interest 2: 32, inside<br />

back cover; 4: 23<br />

— — beetle research at 1: 31–35, 32<br />

— — Bentham and Hooker sequence<br />

at 2: 16<br />

— — Bradley Rosaceous Collection 1:<br />

14, 44; 2: 16, 20, 20; 4: 22, 24<br />

— — Bussey Brook Meadow, in aerial<br />

photo 1: 14<br />

— — Bussey Hill, in aerial photos 1:<br />

11, 13, 14<br />

— — Camellia trials 1: 27<br />

— — cartography systems 1: 12–19<br />

— — Centre Street, in aerial photo<br />

1: 14<br />

— — China expeditions, 1907–1908,<br />

1910 3: 2–13<br />

— — cold-hardiness at 3: 36<br />

— — conifer collection 3: 36; 4: 22<br />

— — crabapple legacy 2: 14–21, back<br />

cover<br />

— — Crataegus at 2: 16<br />

— — cultivar evaluation 2: 18<br />

— — Dana Greenhouses, in aerial<br />

photos 1: 14<br />

— — early accessions 1: 44; 2: 16,<br />

19–20<br />

— — Faxon Pond 2: 32<br />

— — Forest Hills Gate 2: 16<br />

— — Forsythia hybrids at 2: 18<br />

— — Himalayan pine at 3: 36, inside<br />

back cover<br />

— — Hunnewell building, in aerial<br />

photos 1: 15, 15<br />

— — Hydrangea paniculata ‘Praecox’<br />

at 1: inside covers, 44<br />

— — introductions 1: 44; 2: 6, 18–21<br />

— — Japanese and Korean plants at 1:<br />

27, 44; 2: 16<br />

— — Leventritt Shrub and Vine Garden,<br />

aerial photo <strong>of</strong> 1: front cover<br />

— — Living Collections survey 1:<br />

15, 17<br />

— — Master Plan 1: 17<br />

— — Meadow Road 2: 32<br />

— — Malus collection 2: 4, 14–21, 14,<br />

16–21, back cover<br />

— — Metasequoia glyptostroboides<br />

at 4: 23<br />

— — model 1: 18–19<br />

— — Nikko fir, loss <strong>of</strong> 4: 22, 22<br />

— — Peters Hill 2: 14, 16, 16, 18, 19,<br />

19, 20<br />

— — — — in aerial photos 1: 11–12, 14<br />

— — Pinus wallichiana at 3: 36,<br />

inside back cover<br />

— — plant distribution benefits 2: 20<br />

— — Prunus at 1: 13; 2: 18; 4: 24<br />

— — Pyrus 2: 16<br />

— — — pyrifolia at 4: inside covers, 28<br />

— — Rosaceae blights at 4: 22<br />

— — sand pear at 4: 28, inside back<br />

cover<br />

— — Visiting Committee, 1955 1: 15<br />

— — “Wea<strong>the</strong>r Station Data—2009”<br />

4: 20–24<br />

— — Weld Hill in aerial photos 1: 14,<br />

18, 19, 19<br />

— — winter temperatures 3: 36<br />

<strong>Arnold</strong>ia, Index to Volume 66 1:<br />

36–43<br />

— and Donald Wyman 2: 19

Index 35<br />

Arnot Teaching and Research Forest<br />

3: 32, 32<br />

Aronia 3: front/back covers, 14–25,<br />

14–18, 22, 24<br />

— arbutifolia 3: 14–15, 15–19,<br />

21–22, 24<br />

— — flowers 3: 15<br />

— — foliage 3: 15<br />

— — fruit 3: 14<br />

— fruit chemistry 3: 14, 21, 23–25<br />

— — crop potential 3: 19–25<br />

— genetics 3: 19, 21, 22, 24–25<br />

— habitat and range 3: 18–19,<br />

18–20, 21<br />

— hybrids 3: 21, 25<br />

— juice products 3: 22–25, 23<br />

— ‘Likernaya’ 3: 25<br />

— melanocarpa 3: 15–19, 16, 17,<br />

21–25, 22, 24<br />

— — foliage 3: 17, 22<br />

— — fruit 3: front cover, 16, 24<br />

— — growth habit 3: 21, 22<br />

— — ‘Nero’ 3: 24, 25<br />

— — x Sorbus aucuparia 3: 25<br />

— — ‘Viking’ 3: 24, 25<br />

— mitschurini 3: 25<br />

— ploidy and apomixis in 3: 19, 21,<br />

22, 24–25<br />

— prunifolia 3: 15, 18–19, 21, 22<br />

— — x arbutifolia 3: 21<br />

— — x melanocarpa 3: 21<br />

— — x prunifolia 3: 21<br />

— taxonomy 3: 21<br />

— — and Photinia 3: 21<br />

“Aronia: Native shrubs With<br />

Untapped Potential,” Mark Brand 3:<br />

14–25, 14–20, 22–24<br />

Ash, as beetle host 1: 34<br />

— borer, emerald 1: 34<br />

Asia, plants from 1: 20–30, 44; 2: 5,<br />

22–28; 3: 2–13, 36; 4: 28<br />

Asian long-horned beetle (ALB) 1: 34,<br />

34; 2: 29<br />

— medicine, traditional 3: 29–30<br />

Asiatica Nursery [PA] 1: 20–21<br />

Asimina triloba, fruit <strong>of</strong> 3: 28, 28, 30<br />

Astilbes, shade-grown 3: 33<br />

Atomic testing 2: 31<br />

Autumn color 2: 32; 4: 23, 28<br />

“Autumn’s Harbinger: Acer Rubrum<br />

‘Schlesingeri’,” Michael S. Dosmann<br />

2: 32, inside back cover<br />

Auxin pathway 4: 15–19<br />

— exogenous 4: 18<br />

B<br />

Bachtell, Kris, photo by 2: inside<br />

front cover<br />

Bacterial diseases 2: 10; 4: 22<br />

Bamboo, in panda habitat 2: 26<br />

Baoxing, plant exploring in 2: 22–28<br />

Bark beetles, in port <strong>of</strong> Boston 1:<br />

31–32<br />

Basset, Cédric,“In <strong>the</strong> Footsteps <strong>of</strong><br />

Fa<strong>the</strong>r David” 2: 22–28, 22–28<br />

Bayesian approach 4: 11<br />

Beech 3: 31<br />

Beeches, as beetle host 1: 35<br />

Beetle, ambrosia 1: 32<br />

— Asian long-horned (ALB) 1: 34, 34;<br />

2: 29<br />

— emerald ash borer (EAB) 1: 34, 34<br />

— European spruce bark 1: 35<br />

— red-haired pine bark 1: 33, 33<br />

— six-too<strong>the</strong>d bark 1: 33, 33<br />

Beetles, damaging 1: 31–35, 33–4<br />

— — emergence and phenology 1:<br />

32, 35<br />

— — fungal vectors <strong>of</strong> 1: 33, 35<br />

— — links to information 1: 34<br />

— — new surveys and trapping methods<br />

1: 32–35<br />

— — observation <strong>of</strong> 1: 34<br />

Bene, John 3: 27<br />

Bentham, George 4: 26<br />

Bentham and Hooker sequence 2: 16<br />

Berberidaceae 2: 26<br />

Beresowski (<strong>the</strong> botanist) 2: 28<br />

Berks, Robert 4: 27<br />

Berry crops 3: 14–25, 28, 30<br />

“‘Best’ Crabapples (Malus spp.)”<br />

2: chart 9<br />

Betula spp., and exotic beetles 1: 35<br />

“Between Earth and Sky: Our Intimate<br />

Connections to Trees,” Nalini<br />

M. Nadkarni,<br />

[excerpt] 2: 29–31<br />

Bible, quince in 1: 3<br />

Binomial nomenclature 4: 26<br />

Biodiversity 2: 22–23, 24, 28; 3: 6,<br />

11–13, 26, 27, 28<br />

Biology and taxonomy 4: 25–27<br />

Birch spp. 3: 36<br />

Birches, as beetle host 1: 34, 35<br />

Birds 2: 6, 10; 3: 14, 16<br />

“Bird’s-eye Views: Aerial Photographs<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arnold</strong> <strong>Arboretum</strong>,” Sheila<br />

Connor 1: 10–19, 10–19<br />

Black, James W., aerial photography <strong>of</strong><br />

1: 10, 10<br />

Blackberries 3: 28<br />

Blights and 2009 wea<strong>the</strong>r 4: 20, 22<br />

Blooming, premature 4: 24<br />

Blue Ridge Community College 4: 19<br />

Blue stain fungi 1: 33<br />

Boston 133 Cities Urban Area mapping<br />

program 1: 17<br />

Boston port 1: 31<br />

— — invasive beetles and 1: 31–32<br />

Botryosphaeria obtusa 2: 10<br />

Bourg, Ian C., Ph.D. 2: 28<br />

Brand, Mark, “Aronia: “Native shrubs<br />

With Untapped Potential” 3: 14–25<br />