The World Foliage Plant Industry - Acta Horticulturae

The World Foliage Plant Industry - Acta Horticulturae

The World Foliage Plant Industry - Acta Horticulturae

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

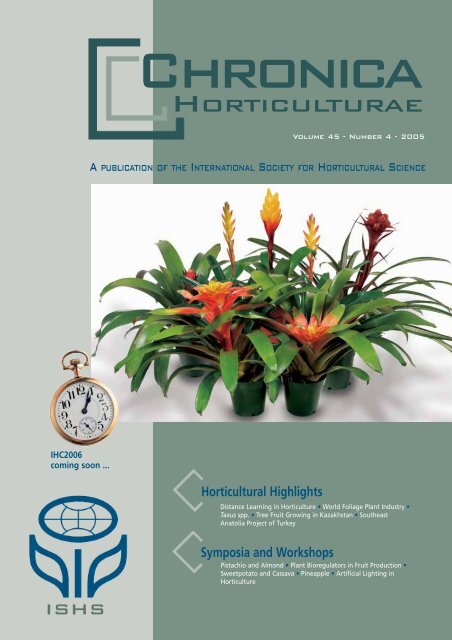

Chronica<br />

HORTICULTURAE<br />

Volume 45 - Number 4 - 2005<br />

A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR HORTICULTURAL SCIENCE<br />

IHC2006<br />

coming soon ...<br />

ISHS<br />

Horticultural Highlights<br />

Distance Learning in Horticulture • <strong>World</strong> <strong>Foliage</strong> <strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Industry</strong> •<br />

Taxus spp. • Tree Fruit Growing in Kazakhstan • Southeast<br />

Anatolia Project of Turkey<br />

Symposia and Workshops<br />

Pistachio and Almond • <strong>Plant</strong> Bioregulators in Fruit Production •<br />

Sweetpotato and Cassava • Pineapple • Artificial Lighting in<br />

Horticulture

Chronica<br />

HORTICULTURAE<br />

Chronica <strong>Horticulturae</strong> © ISBN: 90 6605 057 8 (Volume 45 - Number<br />

4; December 2005); ISSN: 0578-039X.<br />

Published quarterly by the International Society for Horticultural Science,<br />

Leuven, Belgium. Lay-out and printing by Drukkerij Geers, Gent, Belgium.<br />

ISHS © 2005. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced<br />

and/or published in any form, photocopy, microfilm or any other<br />

means without written permission from the publisher. All previous issues<br />

are also available online at www.ishs.org/chronica. Contact the ISHS<br />

Secretariat for details on full colour advertisements (1/1, 1/2, 1/4 page)<br />

and/or mailing lists options.<br />

A publication of the International Society for<br />

Horticultural Science, a society of individuals, organizations,<br />

and governmental agencies devoted to horticultural<br />

research, education, industry, and human<br />

well-being.<br />

CONTENTS<br />

ISHS<br />

Editorial Office and Contact Address:<br />

ISHS Secretariat, PO Box 500, B-3001 Leuven 1, Belgium. Phone:<br />

(+32)16229427, fax: (+32)16229450, e-mail: info@ishs.org, web:<br />

www.ishs.org or www.actahort.org.<br />

Editorial Staff<br />

Jules Janick, Science Editor, janick@purdue.edu<br />

Jozef Van Assche, Managing Editor, jozef@ishs.org<br />

Kelly Van Dijck, Assistant Editor, kelly.vandijck@ishs.org<br />

Peter Vanderborght, Associate Editor - Production & Circulation,<br />

peter.vanderborght@ishs.org<br />

Editorial Advisory Committee<br />

Jules Janick, Purdue University, USA, Chair of the Editorial Advisory<br />

Committee<br />

Tony Biggs, Australian Society of Horticultural Science, Australia<br />

Byung-Dong Kim, Department of <strong>Plant</strong> Sciences and Center for <strong>Plant</strong><br />

Molecular Genetics and Breeding Research, Seoul National University,<br />

Korea<br />

António A. Monteiro, College of Agriculture and Forestry, Technical<br />

University of Lisbon, Portugal<br />

Robert K. Prange, Atlantic Food and Horticulture Resarch Centre,<br />

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada<br />

Manfred Schenk, Institute of <strong>Plant</strong> Nutrition, University of Hannover,<br />

Germany<br />

Membership and Orders of Chronica <strong>Horticulturae</strong><br />

Chronica <strong>Horticulturae</strong> is provided to the Membership for free: Individual<br />

Membership 45 EUR annually (special rate for Individual Members from<br />

selected developing countries: 45 EUR for 2 years), Student Membership<br />

15 EUR per year. For all details on ISHS membership categories and membership<br />

advantages, including a membership application form, refer to the<br />

ISHS membership pages at www.ishs.org/members.<br />

Payments<br />

All major Credit Cards accepted. Always quote your name and invoice or<br />

membership number. Make checks payable to ISHS Secretariat. Money<br />

transfers: ISHS main bank account number is 230-0019444-64. Bank<br />

details: Fortis Bank, Branch “Heverlee Arenberg”, Naamsesteenweg<br />

173/175, B-3001 Leuven 1, Belgium. BIC (SWIFT code): GEBABEBB08A,<br />

IBAN: BE29230001944464. Please arrange for all bank costs to be taken<br />

from your account assuring that ISHS receives the net amount. Prices listed<br />

are in euro (EUR) but ISHS accepts payments in USD as well.<br />

<strong>Acta</strong> <strong>Horticulturae</strong><br />

<strong>Acta</strong> <strong>Horticulturae</strong> is the series of proceedings of ISHS Scientific Meetings,<br />

Symposia or Congresses. (ISSN: 0567-7572). ISHS Members are entitled to<br />

a substantial discount on the price of <strong>Acta</strong> <strong>Horticulturae</strong>. For an updated<br />

list of available titles go to www.ishs.org/acta. A complete and accurate<br />

record of the entire <strong>Acta</strong> <strong>Horticulturae</strong> collection, including all abstracts<br />

and full text articles is available online at www.actahort.org. ISHS<br />

Individual membership includes credits to download 10 full text <strong>Acta</strong><br />

<strong>Horticulturae</strong> articles. All <strong>Acta</strong> <strong>Horticulturae</strong> titles-including those no longer<br />

available in print format-are available in the <strong>Acta</strong>Hort CD-ROM format.<br />

■ News from the Board<br />

3 ISHS Progress and Future Planning: Highlights of the 2005 Board and Executive<br />

Committee Meetings, Lillehammer, Norway, N.E. Looney and I.J. Warrington<br />

5 A Call for Nominations: ISHS Honorary Membership and Fellowship<br />

■ Issues<br />

5 <strong>The</strong> Challenge of Distance Learning in Horticulture, G.R. Dixon<br />

■ Horticultural Science Focus<br />

9 <strong>The</strong> <strong>World</strong> <strong>Foliage</strong> <strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Industry</strong>, J. Chen, D.B. McConnell and R.J. Henny<br />

■ Horticultural Science News<br />

16 Taxus spp.: A Genus of Ever-Useful and Everlasting Evergreens, J.M. DeLong and<br />

R.K. Prange<br />

■ <strong>The</strong> <strong>World</strong> of Horticulture<br />

21 Tree Fruit Growing in Kazakhstan, R.K. Karychev, Y. Salnikov, M.T. Nurtazin and<br />

D. Doud Miller<br />

23 Southeast Anatolia Project of Turkey: Implications for Horticulture, S. Güler<br />

24 New Books, Websites<br />

26 Courses and Meetings<br />

26 Opportunities<br />

■ Symposia and Workshops<br />

26 IVth Int’l Symposium on Pistachio and Almond<br />

29 Xth Int’l Symposium on <strong>Plant</strong> Bioregulators in Fruit Production<br />

31 IInd Int’l Symposium on Sweetpotato and Cassava<br />

32 Vth Int’l Pineapple Symposium<br />

33 Vth Int’l Symposium on Artificial Lighting in Horticulture<br />

■ News from the ISHS Secretariat<br />

35 New ISHS Members<br />

36 Calendar of ISHS Events<br />

37 Available Issues of <strong>Acta</strong> <strong>Horticulturae</strong><br />

38 Index to Volume 45 of Chronica <strong>Horticulturae</strong><br />

40 <strong>The</strong> ISHS in the Tropical <strong>World</strong>: <strong>The</strong> Committee for Research Cooperation (CRC)<br />

Scripta <strong>Horticulturae</strong><br />

Scripta <strong>Horticulturae</strong> is a new series from ISHS devoted to specific horticultural<br />

issues such as position papers, crop or technology monographs<br />

and special workshops or conferences.<br />

Cover photograph: Marketable Bromeliads from Deroose <strong>Plant</strong>s, Inc., Apopka,<br />

Florida. Photo by courtesy of Chris Fooshee, University of Florida, IFAS, Mid-<br />

Florida Research and Education Center, see article p. 9<br />

www.ihc2006.org<br />

ISHS • 2

NEWS FROM THE BOARD<br />

ISHS Progress and Future<br />

Planning: Highlights of the 2005<br />

Board and Executive Committee<br />

Meetings, Lillehammer, Norway<br />

Norman E.<br />

Looney<br />

Norman E. Looney, ISHS President<br />

Ian J. Warrington, ISHS Vice-President<br />

Each annual meeting of the ISHS Executive<br />

Committee (EC), involving the Board and Chairs<br />

of all ISHS Sections and Commissions, is planned<br />

several years in advance. <strong>The</strong> invitation to<br />

host the June 2005 meeting came in 2002 from<br />

the ISHS Council members for Norway,<br />

Professor Roar Moe of the Agricultural<br />

University of Norway and Dr. Lars Sekse of the<br />

Ullensvang Research Centre of <strong>Plant</strong>eforsk. It<br />

was purposely scheduled to overlap the Fifth<br />

International Symposium on Artificial Lighting<br />

that was held at the same venue in picturesque<br />

Lillehammer. As is normal practice, the ISHS<br />

Board met independently just ahead of the EC<br />

meeting. Every meeting room detail, tour and<br />

social event was carefully planned and executed<br />

by our Norwegian hosts - the result being a<br />

very productive and enjoyable week for all<br />

Symposium participants and Society leaders.<br />

THE BOARD MEETING<br />

Ian J. Warrington<br />

Reports from the Secretariat and each Board<br />

member revealed the healthy financial state of<br />

the Society, the success we are having in improving<br />

web resources and diversifying our publications,<br />

the impressive growth in membership,<br />

and the smooth functioning of the Secretariat.<br />

<strong>The</strong> efficiency of the latter is illustrated by the<br />

fact that 22 of the expected 34 volumes of <strong>Acta</strong><br />

<strong>Horticulturae</strong> to be published in 2005 were<br />

completed and distributed by mid-year.<br />

We learned that recent efforts to attract new<br />

Country-State members from the developing<br />

ISHS Board* and Executive Committee. From left to right: Lyle Craker, Ayman Abou-Hadid, Robert K. Prange, Johan van Scheepen, Gert Groening,<br />

Norman E. Looney*, Jules Janick*, Isabel Ferreira, Kim Hummer, Robert J. Bogers*, Uygun Aksoy*, Ian J. Warrington*, John Erwin, Alfons Vanachter,<br />

Víctor Galán Saúco, Omer Verdonck, Daniel J. Cantliffe, Ted DeJong, Peter Oppenheim, Geoffrey R. Dixon, Jung-Myung Lee*, Errol W. Hewett,<br />

Sadanori Sase, Gene Albrigo, Jozef Van Assche*, Ben Ami Bravdo, Carmine Damiano.<br />

CHRONICA HORTICULTURAE •VOL 45 • NUMBER 4 • 2005 • 3

Scenic beauty of Norway.<br />

world are proving very successful. With the<br />

addition of Indonesia, Nigeria, and Tanzania,<br />

the ISHS Council now represents 52 countries.<br />

Furthermore, the Executive Director reported<br />

that discussions are well advanced with five<br />

other countries. <strong>The</strong> Board is hopeful that the<br />

2006 meeting of Council (at IHC2006 in Seoul)<br />

will set a new record for country representation.<br />

Every country that has expressed an interest in<br />

joining the Society will be invited to send observers.<br />

As per recent changes to the Rules, low<br />

income countries represented at Seoul will be<br />

granted Category IV membership status for one<br />

year.<br />

Much discussion at this meeting related to rethinking<br />

the long-standing category of<br />

“Organizational Membership” in the Society.<br />

Efforts by this Board to extend the reach of ISHS<br />

through strategic partnerships with international<br />

development agencies and other organizations<br />

is largely behind this initiative. To illustrate,<br />

while ISHS has long had a healthy working<br />

arrangement with FAO, a United Nations body<br />

that supports several of our Working Groups,<br />

we have not had a way to recognize FAO as an<br />

official partner. This will change with the introduction<br />

of a new category of association to be<br />

called ISHS Partners. This designation will recognize<br />

those agencies and organizations with<br />

which ISHS has a negotiated agreement and a<br />

clear business relationship - Partners support<br />

the Society in some substantial way while ISHS<br />

contributes importantly to their business.<br />

Another good example is the International<br />

Horticultural Congress.<br />

In addition to the FAO, we see several of the<br />

CGIAR Future Harvest Centers, the <strong>World</strong><br />

Vegetable Center (AVRDC), the European<br />

Union’s Technical Centre for Agricultural and<br />

Rural Cooperation (CTA), and France’s Centre de<br />

Coopération Internationale en Recherche<br />

Agronomique pour le Développement -<br />

Département Productions Fruitières et Horticoles<br />

(CIRAD-Flhor) as being strong candidates for<br />

ISHS Partner recognition. It would also seem<br />

appropriate that our recently concluded arrangements<br />

with the International Society of<br />

Citriculture and the International Peat Society be<br />

recognized with the ISHS Partner designation.<br />

What were previously called Organizational<br />

Members will now be called Institutional<br />

Members. For an annual fee the Society provides<br />

publications and access to web-based<br />

resources to research centers, libraries, and<br />

other public sector institutions.<br />

And finally, in recognition of the growing proportion<br />

of ISHS members working in the private<br />

sector, there will be a new non-voting category<br />

of “membership” called Corporate<br />

Associates. Here, for an annual fee reflecting<br />

the package of products and services requested,<br />

Corporate Associates will be recognized as<br />

supporters of the Society and at the same time<br />

receive valuable products and services for their<br />

professional staff.<br />

<strong>The</strong> next Board meeting is set for Rome in early<br />

December. In addition to dealing with the normal<br />

agenda of Society business the Directors<br />

will hold meetings with senior officials of FAO<br />

and its Global Forum for Agricultural Research<br />

(GFAR). <strong>The</strong>y will also sign a Memorandum of<br />

Understanding with the Global Crop Diversity<br />

Trust - a document recognizing ISHS and its<br />

Commission on <strong>Plant</strong> Genetic Resources as key<br />

players in the community of scientists engaged<br />

in protecting and improving horticultural crop<br />

genetic resources. <strong>The</strong> GCDT is the “action<br />

arm” of the International Treaty for <strong>Plant</strong><br />

Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture<br />

and is administered by staff at FAO and at the<br />

International <strong>Plant</strong> Genetic Resources Institute<br />

(IPGRI), also in Rome.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se meetings are seen by the Board as being<br />

key to our goal of achieving greater cooperation<br />

with FAO and the CGIAR (represented in<br />

Rome by IPGRI). Thus, there was much discussion<br />

at Lillehammer about how to get the most<br />

from these consultations.<br />

THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE<br />

MEETING<br />

<strong>The</strong> Executive Committee, chaired by the ISHS<br />

Vice-President, also had a very full schedule of<br />

business to consider at the Lillehammer meeting.<br />

It was a pleasure to welcome to the meeting<br />

the Chairs of the new Section on Citrus<br />

(Dr. Gene Albrigo) and Commission on<br />

Sustainability through Integrated and Organic<br />

Horticulture (Dr. Robert Prange). <strong>The</strong> EC continues<br />

to review the depth and breadth of the<br />

Society’s scientific activities. In that regard, an<br />

area of growing interest is the many contributions<br />

that fruits and vegetables make to human<br />

health and well-being. A major ISHS conference<br />

on this topic was recently held in Canada<br />

(Québec, August 2005). A new Working Group<br />

has now been formed to ensure that the<br />

momentum gained in this area is not lost and a<br />

proposal to launch a new Commission on<br />

Horticulture and Human Health will be before<br />

the EC at its next meeting (at IHC2006 in<br />

Korea).<br />

<strong>The</strong> forward schedule of new symposia approved<br />

or re-confirmed at Lillehammer is very<br />

impressive - the essential information about<br />

each is posted at www.ishs.org (click on<br />

Calendar of Events). Every effort is made to<br />

avoid clashes in the overall symposia programme<br />

and feedback is welcomed at any time on<br />

improvements that might be considered.<br />

Much attention was devoted to the next<br />

International Horticultural Congress and<br />

Exhibition to be held in Seoul on August 13-19,<br />

2006. Members will now have received the<br />

Second Announcement and Call for Papers, a<br />

late draft of which was discussed in depth by<br />

the Board and EC at Lillehammer. <strong>The</strong> EC was<br />

pleased by the exciting line-up of scientific symposia,<br />

the very interesting colloquia and the<br />

intention to have a major exhibition on horticulture<br />

that will be open to the public throughout<br />

the Congress. <strong>The</strong> schedule of Workshops and<br />

Working Group Meetings is still very much<br />

under development - there is still time to forward<br />

suggestions to IHC President Lee and his<br />

organizing team for consideration.<br />

It is important to point out that the ISHS Vice-<br />

President and Executive Committee have had<br />

significant input during the development of<br />

IHC2006. It will be a Congress that every horticultural<br />

science professional will want to<br />

attend!<br />

<strong>The</strong> Rules of the Society require that leadership<br />

at all levels is renewed regularly. <strong>The</strong> leadership<br />

of our Sections and Commissions is no exception<br />

and some ten EC members will become<br />

ineligible to stand for re-election at the time of<br />

the Seoul Congress. Thus, it is certain that there<br />

will be new leaders of the three Sections<br />

dealing with Vegetables, Tropical and<br />

Subtropical Fruits, and Medicinal and Aromatic<br />

<strong>Plant</strong>s. Likewise, the Chairs of seven<br />

Commissions: Economics and Management,<br />

Education and Training, Landscape and Urban<br />

Horticulture, <strong>Plant</strong> Protection, <strong>Plant</strong> Substrates,<br />

Protected Cultivation, and Quality and Postharvest<br />

Horticulture, will retire at Seoul. Every<br />

Society member belonging to one or more of<br />

these Sections and/or Commissions is urged to<br />

watch for the Call for Nominations and to consider<br />

offering his or her energy, ideas and experience.<br />

One consideration to keep in mind<br />

during this leadership renewal process is that<br />

the number of women holding ISHS leadership<br />

positions is well below what it should be.<br />

Leadership of a Section or Commission is a<br />

rewarding experience and provides the opportunity<br />

to make an important contribution to our<br />

profession.<br />

ISHS • 4

A Call for Nominations: ISHS Honorary<br />

Membership and Fellowship<br />

Nominations for new Honorary Members and Fellows of the ISHS will be considered by<br />

the Council at its meeting in Korea next year. Any nomination for this should be received<br />

at the Secretariat not later than April 15th, 2006, for consideration by the ISHS<br />

Nomination and Award Committee and the ISHS Board prior to the meeting of the<br />

Council.<br />

ISHS HONORARY<br />

MEMBERSHIP<br />

Honorary Membership, the Emeritus Award of<br />

the ISHS, is given by the Council to a person<br />

who is a member of the ISHS, at the end of<br />

his/her career, in recognition of his/her outstanding<br />

service to the Society. A certificate will be<br />

given to the recipients of this ISHS Award.<br />

ISHS FELLOWSHIP<br />

<strong>The</strong> ISHS Fellowship is presented to any person,<br />

regardless of his/her age, ISHS member or nonmember,<br />

in recognition of this person’s out-<br />

standing contribution to horticultural science<br />

worldwide and/or for his/her meritorious service<br />

on behalf of the Society. A precious metal<br />

pin and a certificate is given to the recipients of<br />

this ISHS award. <strong>The</strong> total number of ISHS<br />

Fellows should not exceed 1% of the total<br />

membership, averaged over a period of 4 years.<br />

PROCEDURE<br />

<strong>The</strong> ISHS Nominations and Awards Committee<br />

(hereafter: ‘<strong>The</strong> Committee’) invites the members<br />

of the Society, through this announcement<br />

in Chronica <strong>Horticulturae</strong>, to bring possible<br />

candidates for an ISHS Honorary Membership<br />

and Fellowship to the attention of the Society.<br />

Nominations should be accompanied by five<br />

letters of support, giving reasons why a nominee<br />

is considered worthy of an honour; these<br />

letters must come from members in no less<br />

than three different countries. Nominations<br />

must be received by the Executive Director at<br />

least three months prior to the Council meeting.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Executive Director will collect the suggestions<br />

and will send these, together with the<br />

letters of support, to ‘<strong>The</strong> Committee’. After<br />

consideration by ‘<strong>The</strong> Committee’ and the ISHS<br />

Board, the suggestions received and motivated<br />

recommendions will be presented to the<br />

Council, which will decide who will receive the<br />

Awards. <strong>The</strong> presentation ceremony will take<br />

place at the next Congress (IHC2006 Seoul,<br />

Korea) during the General Assembly of the<br />

ISHS.<br />

ISSUES<br />

<strong>The</strong> Challenge of Distance Learning in<br />

Horticulture<br />

Geoffrey R. Dixon<br />

Education in any discipline and at any level of<br />

attainment should increase the student’s<br />

powers of understanding, deduction, integration<br />

and prediction based on an enhanced<br />

store of knowledge. It should not be the accumulation<br />

and regurgitation of information that<br />

is readily available in reference books and the<br />

<strong>World</strong>-Wide-Web. Learning how to use information<br />

to build knowledge and scholarship in<br />

an integrative manner is the essence of an<br />

effective education.<br />

Most systems of education are dependent on<br />

public tax raised finance to a greater or lesser<br />

extent. As a consequence, political priorities for<br />

simplification (modularisation or unitisation),<br />

mass delivery, increased speed, reduced cost,<br />

and provision for career changes have become<br />

dominating and driving forces in the formulation<br />

of public education. <strong>The</strong>se processes are<br />

frequently clothed in the framework of the<br />

“market economy” and encapsulated in terms<br />

such as “value for money,” “satisfying customer<br />

demands,” “achieving client satisfaction”<br />

and “student-centred learning.” <strong>The</strong> underlying<br />

logic of pedagogical arguments that shift education<br />

towards learning as opposed to teaching<br />

have much to recommend them. This shift<br />

does, however, require greater provision of<br />

human and physical resources if it is to improve<br />

education and this adds to the overall costs of<br />

education. Without such increased financial<br />

investment the student-centred learning<br />

approach levels down education and erodes<br />

scholarship.<br />

Some educationists and more particularly policy<br />

makers and politicians see electronic delivery at<br />

a distance as one route towards student-centred<br />

learning as opposed to teaching-centred<br />

learning that avoids the penalty of increasing<br />

costs. Experience shows that the reverse is true<br />

and that good quality, effective distance learning<br />

provided by electronic delivery demands<br />

an investment in teaching staff and resources<br />

that is at least on a par with face-to-face learning.<br />

This article considers the particular requirements<br />

for an education in horticulture and<br />

how these may be satisfied by electronic distance<br />

delivery using examples from leading centres<br />

of excellence.<br />

WHAT IS EDUCATION IN<br />

HORTICULTURE?<br />

Traditionally education in horticulture has integrated<br />

the relevant arts, sciences, humanities<br />

and husbandries into students’ knowledge<br />

bases that allowed entry into widely differing<br />

careers with a considerable span of responsibilities<br />

(Dixon, 2005). Essentially this is not radically<br />

different to the education offered to engineers<br />

or architects.<br />

Face-to-face education in each of these disciplines<br />

demanded the availability of a large tea-<br />

CHRONICA HORTICULTURAE •VOL 45 • NUMBER 4 • 2005 • 5

ching staff composed of individuals possessing<br />

specialist knowledge and expertise. An additional<br />

luxury offered to horticultural students was<br />

that institutions attempted to maintain small<br />

areas of production for a multitude of different<br />

vegetable, fruit, and protected ornamental<br />

crops. <strong>The</strong> force of institutional finances has<br />

largely consigned the latter luxury to history<br />

except in a few cases of special provision such<br />

as the Niagara Parks Department, Canada<br />

(Klose and Whitehouse, 2004) (Fig. 1) or the<br />

Royal Botanic Gardens in Great Britain.<br />

<strong>The</strong> essential elements for an education in horticulture<br />

are firstly, knowledge drawn from<br />

across a wide range of interrelating subjects<br />

and secondly, exposure to and involvement<br />

with the practical and sustainable manipulation<br />

of plant growth and reproduction. Delivery of<br />

the first part of these requirements at least<br />

should be amenable to electronic delivery at a<br />

distance.<br />

WHAT IS DISTANCE<br />

LEARNING?<br />

Distance learning is any situation whereby the<br />

teacher and student are separated by space and<br />

possibly by time. <strong>The</strong> greatest experience with<br />

this form of learning is probably in Australia<br />

which boasts a world renowned educational<br />

system for school-age children living in the<br />

“outback” based originally on the use of radio.<br />

In Great Britain the Open University was founded<br />

in the 1960s and continues offering very<br />

successfully high quality undergraduate education<br />

in most disciplines based initially on the<br />

use of television. Teachers across the USA<br />

pioneered the use of video systems from the<br />

late 1970s onwards. <strong>The</strong> advent of the <strong>World</strong>-<br />

Wide-Web (www) and easy availability of low<br />

cost electronic desk and laptop computers<br />

expands the opportunities for distance learning<br />

to an unlimited extent.<br />

MANAGING THE DILEMMA<br />

OF QUALITY AND QUANTITY<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>World</strong>-Wide-Web offers students access to<br />

oceans of information (Scott and Dixon, 2004)<br />

and a myriad of courses. It becomes ever more<br />

important that the student is capable of rejecting<br />

or ignoring irrelevant information and able<br />

to concentrate on nub issues and differentiate<br />

between valuable and useless courses. Huge<br />

numbers of educational institutions world-wide<br />

are now offering courses via electronic means.<br />

Students in one country can sign up and pay<br />

electronically for courses originating on the<br />

other side of the planet in the matter of a few<br />

minutes. This might be termed “fast-food education”<br />

(England, 2005). <strong>The</strong> plethora of<br />

courses raises the question of how the students<br />

differentiate between them especially as initially<br />

they will have only limited knowledge on<br />

which to make a quality judgement. It is feasible<br />

to take the free-market approach of “buyer<br />

beware” (caveat emptor) but is that fair to users<br />

who do not have the knowledge with which to<br />

make informed choices?<br />

Certainly it is not possible to police or even<br />

mildly regulate what is placed on the web in the<br />

name of horticultural education. It does however,<br />

behove professionals such as members of<br />

the International Society for Horticultural<br />

Science (ISHS) to ensure that material for which<br />

they are responsible is fit for the purpose that is<br />

claimed. National horticultural professional<br />

bodies, especially those offering “Continuing<br />

Professional Development” (CPD) to their members,<br />

have responsibilities to ensure the veracity<br />

of web based courses accepted for such schemes.<br />

<strong>The</strong> situation is more straightforward where<br />

web courses are offered by bona fide educational<br />

institutions as part of their existing provision<br />

for awards, such as colleges and universities,<br />

leading on to their degree structures. Here the<br />

institutions, particularly in Europe and increasingly<br />

Australia, are regulated for the quality of<br />

their provision. Alternatively the courses may<br />

adhere to a format and even content that has<br />

been designed by the awarding body and yet<br />

may be delivered by other organisations. This is<br />

the case with the development of a modularised<br />

form of the Master of Horticulture (M.<br />

Hort.) qualification of the Royal Horticultural<br />

Society of London, which is amenable to delivery<br />

in an electronic form.<br />

SUCCESSFUL ELECTRONIC<br />

DELIVERY AT A DISTANCE<br />

<strong>The</strong> key feature regarding the use of electronic<br />

delivery at a distance is that the original teacher<br />

should totally review and revise what is to be<br />

learnt and analyse the substance of the traditional<br />

course in great depth. It is essential to offer<br />

in the electronic format rounded core issues<br />

that form the key components of the topic<br />

being considered. Electronically delivered<br />

courses should not take the form of simply a set<br />

of lecture notes posted on the web. If they do<br />

then the teacher is short changing the student<br />

Figure 1. <strong>The</strong> Niagara Parks Botanic Garden.<br />

in a reprehensible manner. Many other aspects<br />

of electronic provision are similar to those for<br />

conventional delivery. Indeed where courses<br />

have been transferred to the virtual classroom,<br />

it is found that the problems thrown up by distance<br />

student are remarkably similar to those<br />

normally encountered in face-to-face delivery.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is of course a running-in phase when the<br />

electronic software is being tested for reliability<br />

and robustness but once this is concluded most<br />

problems can be resolved by access to appropriate<br />

members of staff, either in real time or<br />

via bulletin boards and email addresses. It is<br />

found that distance students make use of each<br />

other’s knowledge and expertise in a similar<br />

fashion to those in a physical classroom.<br />

Experiences and abilities are shared and valued<br />

by the student body. This is important because<br />

it enables distance students to develop the<br />

camaraderie of conventional peer groups.<br />

Much the most important element is that students<br />

should have reliable and scheduled access<br />

to members of staff for mentoring and tuition.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re should also be provision for a rapid response<br />

where there are software problems so<br />

that electronic faults do not impede the process<br />

of learning and submission of course work. <strong>The</strong><br />

latter is of especial importance where<br />

assignments require to be submitted by specified<br />

dates.<br />

ELECTRONIC COURSES FOR<br />

DISTANCE DELIVERY<br />

Examples of courses leading towards a recognised<br />

award are typified by the Degrees awarded<br />

in Arboriculture, Horticulture, and Turf Science<br />

offered electronically by Myerscough College in<br />

collaboration with the University of Central<br />

Lancashire, Preston, UK (Anon, 2005). <strong>The</strong>se<br />

courses have been transferred successfully from<br />

the traditional face-to-face full time classroom<br />

format to part time delivery by electronic means<br />

(Fig. 2). This requires the student to commit 15<br />

hours per week for the duration of the course<br />

that may require several years. <strong>The</strong>se courses<br />

are divided into an established framework of<br />

ISHS • 6

Figure 2. Teaching tree anatomy by electronic distance learning. Picture by courtesy of Dr. Julie<br />

Young and Myerscough College, UK.<br />

modules that are completed in a regulated<br />

manner. Progress is measured by the fulfilment<br />

of course work assignments and end of year<br />

examinations. Details of the courses can be<br />

obtained from: www.myerscough.ac.uk<br />

At a higher level still the University of<br />

Melbourne, Australia offers masters courses in<br />

agribusiness by distance learning. <strong>The</strong>se are<br />

especially suited to students who have several<br />

years experience and may be reaching the ranks<br />

of middle and upper management (Anon,<br />

2004; McSweeney, 2005).<br />

Alternatively single courses may be designed to<br />

achieve more limited but specific targets within<br />

a larger program. This provides an easy and<br />

effective means of teaching crop yield and density<br />

relationships to distance students. It enables<br />

students to examine a wider range of production<br />

variables that impact on crop yield than if<br />

real crops were grown. VirtualCarrots is an<br />

online tool designed to improve students’<br />

understanding and lecturers’ teaching of yielddensity<br />

relationships in field crops (MacKay et<br />

al., 2005, email: b.mackay@masey.ac.nz). With<br />

VirtualCarrots (Fig. 3) students “grow” crops of<br />

carrots under a range of production variables<br />

Figure 3. Teaching plant density x yield relationships using the Virtual Carrot. Picture by<br />

courtesy of Dr. Bruce MacKay and Massey University, New Zealand.<br />

(e.g. required marketable size, time of year,<br />

location and density). VirtualCarrots generates<br />

sets of data and graphs that students evaluate<br />

and interpret based on their theoretical understanding<br />

of yield and density relationships.<br />

Students can, for example, examine the influence<br />

of sowing density, sowing dates, and cultivar<br />

differences for prescribed market yields and harvest<br />

dates by instantly “growing” crops of carrots<br />

on-line. <strong>The</strong>y can examine relative outcomes<br />

for a range of prescribed conditions (e.g.<br />

how is root size distribution influenced by<br />

sowing pattern?). For each set of input variables,<br />

VirtualCarrots generates predicted yield<br />

quantity and quality data sets in a downloadable<br />

form for subsequent off-line analysis and<br />

interpretation by students.<br />

A widespread failing of many on-line university<br />

courses is that they replicate passive and traditional<br />

pedagogical methods in an on-line environment.<br />

Without the opportunity to participate<br />

and interact with case studies and problemsolving<br />

activities students do not engage with<br />

on-line content. This results in poor learning<br />

achievement. Sites with good practice that<br />

avoid these pitfalls are found for example at:<br />

www.hort.purdue.edu.<br />

New Zealand and USA researchers (MacKay and<br />

Fisher, 2005) have developed a case study based<br />

on nutrient toxicity symptoms for a glasshouse<br />

flower crop. This includes photographic and<br />

text descriptions of the problem and a series of<br />

laboratory tests that provide additional data.<br />

But there is a “cost” to purchase the added<br />

information. This case study was presented to<br />

students, growers, and educators using an<br />

internet based tool for case studies in horticultural<br />

education - the Ramosus maze. Ramosus is<br />

an active learning tool, based on the maze<br />

metaphor of a simulated situation created to<br />

mimic the strategic decision-making of real life<br />

(Fig. 4). Users commented that Ramosus provides<br />

users with “the feel of the real situation”<br />

and made them think “diagnostically.”<br />

Ramosus encourages deep learning and adds<br />

value to on-line courses, by balancing the need<br />

to increase the student’s knowledge base and<br />

their use of that knowledge. <strong>The</strong> ability to track<br />

student progress through the maze also provides<br />

additional feedback to instructors on the<br />

student’s level of knowledge and ability to integrate<br />

concepts.<br />

CAN SKILLS BE DELIVERED<br />

AT A DISTANCE?<br />

Distance learning opens up opportunities for<br />

learning practical skills that require the use of<br />

tools and hand manipulation which have previously<br />

been taught by face-to-face instruction,<br />

demonstration, and practice with immediate<br />

(synchronous) feedback, e.g. budding and grafting.<br />

Hennigan and Mudge (2004) set up the<br />

course “<strong>The</strong> How, When and Why of Grafting”<br />

(http://www.instruct1.cit.cornell.edu/courses/ho<br />

rt494/mg/index.html) which embraces top<br />

CHRONICA HORTICULTURAE •VOL 45 • NUMBER 4 • 2005 • 7

Figure 4. Teaching plant nutrient demand and fertiliser applications using the Ramosus Maze.<br />

Picture by courtesy of Dr. Bruce MacKay and Massey University, New Zealand.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

wedge grafting, chip budding and t-budding.<br />

Student grafting was evaluated by them on<br />

basis of pressure, avoidance of desiccation, and<br />

cambial alignment. This program was tested in<br />

a statistically validated experiment that showed<br />

that students could effectively learn grafting by<br />

distance learning equally as well as by face-toface<br />

methods.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Maryland Nursery Crops Nutrient and<br />

Water (Lea-Cox et al., 2004) program provides<br />

tuition for campus based and off-campus students<br />

and industry professionals. <strong>The</strong>re is a problem-based<br />

approach by which students analyse,<br />

synthesise, and evaluate information enabling<br />

them to create and implement on site<br />

water and nutrient management plans for individual<br />

nursery and glasshouse operations. <strong>The</strong><br />

course consists of six content modules covering<br />

science or subject matter necessary to understand<br />

the nutrient and water management<br />

planning processes. <strong>The</strong>se modules are supported<br />

and enhanced by text resources, hypertext<br />

links to external websites and resources, photographs,<br />

graphic illustrations, powerpoint presentations<br />

and video clips.<br />

An unusual part of this scheme is that growers,<br />

consultants, extension professionals and students<br />

are partnered into teams. Each team writes<br />

a management plan for a real nursery or<br />

glasshouse (usually the operation of the grower<br />

on the team) during the course. By interacting<br />

as teams students not only apply theoretical<br />

knowledge from the course, but also learn from<br />

the experiential knowledge of the various professionals<br />

on the team, in situations where they<br />

are faced with solving real-life challenges. <strong>The</strong><br />

actual nursery or glasshouse site used in the<br />

case study is a unique resource that is integral<br />

to the course. Students are not given a theoretical<br />

paper-based case study to work on but a<br />

real operating nursery or glasshouse site from<br />

which to collect data and prepare a nutrient<br />

management plan. <strong>The</strong> assignments are therefore<br />

based in reality. Student progress is evaluated<br />

by several means including quizzes, the<br />

quality of participation in discussion forums,<br />

individual and team assignments posted to the<br />

students and ultimately the quality of the team<br />

project - the water and nutrient management<br />

plan. <strong>The</strong>re is no final examination for this<br />

course. <strong>The</strong> nutrient management plan is the<br />

main assessment tool that is used to ascertain<br />

whether a student is competent. Final plans are<br />

signed by a certified nutrient management<br />

planner and submitted for final review by officials<br />

of the Maryland Department of<br />

Agriculture, the regulatory authority in<br />

Maryland. This electronically delivered course<br />

makes particularly admirable use of the interactions<br />

between students; the manner by which<br />

they learn from the experiences of others is<br />

especially good practice.<br />

THE FUTURE<br />

Electronic delivery at a distance is a major addition<br />

to the manner by which horticultural education<br />

is provided around the world. It provides<br />

many new opportunities for a discipline that<br />

provides the intellectual base and drive for a<br />

major global industry. Educationists specialising<br />

in the discipline of horticulture have responsibilities<br />

to ensure that such courses are of the<br />

highest possible quality and fitness for purpose.<br />

This can only be achieved by dialogue within<br />

our peer group. <strong>The</strong> ISHS provides the opportunity<br />

for this dialogue through Symposia such as<br />

that held in Perth, Western Australia in 2004<br />

and at the International Horticultural<br />

Congresses. At the IHC planned for Seoul,<br />

Korea in 2006 there will be opportunities for<br />

scholars and educationists in horticulture to discuss<br />

this and related topics. Come along and<br />

benefit from and contribute to these meetings.<br />

Anon. 2004. Master of Agribusiness Online. <strong>The</strong><br />

University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia,<br />

available<br />

at<br />

http://www.agribusiness.unimelb.edu.au<br />

Anon. 2005. Foundation degrees in arboriculture<br />

and turf grass science online. Myerscough<br />

College, Preston, United Kingdom, available at<br />

http://www.myerscough.ac.uk<br />

Dixon, G.R. 2005. A review of horticulture as an<br />

evolving scholarship and the implications for<br />

educational provision. <strong>Acta</strong> Hort. 672:25-34.<br />

England, V. 2005. Thai students forced to get a<br />

loan for ‘fast-food’ education. <strong>The</strong> Times<br />

Higher Education Supplement published 6th<br />

May, p.10.<br />

Hennigan, K. and Mudge, K.W. 2004. Effect of<br />

interactivity and learning style on developing<br />

hands-on horticultural skills via distance learning.<br />

<strong>Acta</strong> Hort. 641:85-89.<br />

Klose, E. and Whitehouse, D. 2004. <strong>The</strong> Niagara<br />

Parks Commission School of Horticulture. <strong>Acta</strong><br />

Hort. 641:145-146.<br />

Lea-Cox, J.D., Ross, E.N., Varley, E.N. and Teffeau,<br />

K.M. 2004. A webCT-based distance learning<br />

course to teach water and nutrient management<br />

planners for the nursery and greenhouse<br />

industries. <strong>Acta</strong> Hort. 641:101-110.<br />

MacKay, B.R., Reid, J. and Love, R. 2005.<br />

VirtualCarrots: an online tool for teaching yield<br />

x density relationships. <strong>Acta</strong> Hort. 672:227-231.<br />

MacKay, B.R. and Fisher, P.R. 2005. Interactive<br />

case studies on the internet: the Ramosus maze<br />

tool. <strong>Acta</strong> Hort. 672:217-225.<br />

McSweeney, P. 2005. Experiences in delivering<br />

the University of Melbourne’s Master of<br />

Agribusiness online. <strong>Acta</strong> Hort. 672:257-264.<br />

Scott, P.R. and Dixon, G.R. 2004. Knowledge<br />

management for science-based decision<br />

making. <strong>Acta</strong> Hort. 642:115-118.<br />

ABOUT THE AUTHOR<br />

Geoffrey R. Dixon<br />

Professor Geoffrey R. Dixon, University of<br />

Strathclyde, Glasgow and GreenGene International,<br />

UK, is Chairman of the ISHS Commission<br />

for Education and Training. He is a Council<br />

Member for the UK, Immediate Past President of<br />

the Institute of Horticulture, and Vice-President<br />

(Science Policy) of the Institute of Biology.<br />

Email: 113541.1364@compuserve.com<br />

ISHS • 8

HORTICULTURAL SCIENCE FOCUS<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>World</strong> <strong>Foliage</strong> <strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Industry</strong><br />

Jianjun Chen, Dennis B. McConnell and Richard J. Henny<br />

During the last century and a half, the foliage<br />

plant industry has become truly global.<br />

<strong>The</strong> current situation can be simplified as<br />

four centers of foliage plant origins (Africa,<br />

Asia, Australia, and Central and South<br />

America), four regions producing propagules<br />

(Asia, Central and South America, Europe,<br />

and North America), and three regions of<br />

finished plant production (Asia, Europe, and<br />

North America). Today someone living in<br />

Poland may be watering a Dieffenbachia cultivar<br />

in his home that was initially propagated<br />

in a tissue culture laboratory in China,<br />

finished in the United States, and then sold<br />

at the Aalsmeer auction in the Netherlands.<br />

That scenario omits the fact that the<br />

Dieffenbachia species used to develop the<br />

cultivar were collected in Brazil and<br />

Colombia and then hybridized in England!<br />

Figure 1. Potted foliage plants: (A) Codiaeum, (B) Monstera, (C) Cordyline, (D) Tacca, (E)<br />

Nepenthea, (F) Dracaena, (G) Anthurium, (H) Alocasia, (I) Syngonium, (J) Vriesea, (K)<br />

Aglaonema, (L) Chlorophytum, (M) Calathea, (N) Spathiphyllum, (O) Guzmania, (P)<br />

Philodendron, (Q) Dieffenbachia, (R) Schefflera.<br />

<strong>Foliage</strong> plants, defined literally, would include<br />

all plants grown for their beautiful leaves rather<br />

than for flowers or fruits. In general horticultural<br />

terms, foliage plants are those with attractive<br />

foliage and/or flowers that are able to survive<br />

and grow indoors (Fig. 1). Thus, foliage<br />

plants are used as living specimens for interior<br />

decoration or interior plantscaping (Fig. 2). In<br />

common terminology, foliage plants are referred<br />

to as houseplants. However, in the tropics<br />

they may also be grown under shade as landscape<br />

plants (Fig. 3).<br />

Starting from cuttings, tissue cultured liners, or<br />

seeds, foliage plants are generally produced in<br />

soilless media confined by containers in shaded<br />

greenhouses or shadehouses. Some foliage<br />

plants used as interiorscape trees are grown in<br />

full sun for the first part of their production<br />

cycle, and then grown under shade. Regardless<br />

of their specific production protocols, all plants<br />

have to be managed properly including light,<br />

temperature, water, fertilization, and pest control<br />

until they approach marketable sizes called<br />

finished plants (Chen et al., 2005). <strong>The</strong> plants<br />

are then acclimatized, graded, and shipped to<br />

destinations for interiorscaping. Acclimatization<br />

is a seriate procedure in which light intensity,<br />

nutrient supply, and irrigation frequency are<br />

reduced to anatomically and physiologically<br />

alter the plant so that it will survive and even<br />

thrive after shipping and placement in an interior<br />

environment. Small pot plants may require<br />

several weeks to acclimatize, while large<br />

interior trees may require a minimum of six<br />

CHRONICA HORTICULTURAE •VOL 45 • NUMBER 4 • 2005 • 9

Figure 2. <strong>Foliage</strong> plants used for interiorscaping: (A) Hotel lobby in Orlando, Florida, (B)<br />

Convention center, Kissimmee, Florida, (C) Anthurium with water fall in hotel in Nashville,<br />

Tennessee, and (D) Bamboo palm (Chamaedorea elegans) in office lobby.<br />

months. <strong>The</strong>refore, the complete foliage plant<br />

cycle comprises: (1) plant propagation via tissue<br />

culture, rooting of cuttings, or seed germination;<br />

(2) production of marketable plants from<br />

tissue cultured liners, rooted cuttings, or seedlings;<br />

and (3) postproduction plant care, including<br />

shipment, interiorscape installation, and<br />

maintenance.<br />

Because of their varied growth habits, multitude<br />

of foliar charms, brilliant patterns of leaf<br />

variegation and texture, elegant flower shapes<br />

and colors, as well as tolerance to low light<br />

levels, foliage plants have become an integral<br />

part of contemporary design for building interiors<br />

and play an important role in our daily<br />

lives. <strong>Plant</strong>s bring beauty and comfort to our<br />

surroundings, contribute to the psychological<br />

well-being of people, and remind us of nature<br />

(Manaker, 1997). In addition, plants in building<br />

interiors reduce dust, act as natural humidifiers<br />

(Lohr and Pearson-Mims, 1996), and purify<br />

indoor air. A NASA-funded project concluded<br />

that foliage plants can remove nearly 87% of<br />

air pollutants from sealed chambers within 24<br />

hours. For example, each Peace Lily<br />

(Spathiphyllum ‘Mauna Loa’) plant removed 16,<br />

27, and 41 mg formaldehyde, trichloroethylene,<br />

and benzene, respectively, from sealed<br />

chambers after a 24-hr exposure to the respective<br />

chemical (Wolverton et al., 1989). Later,<br />

researchers at the Oak Ridge National<br />

Laboratory (Cornejo et al., 1999), from<br />

Germany (Giese et al., 1994), Australia (Wood<br />

et al., 2002), and Japan (Oyabu et al., 2003)<br />

also demonstrated that foliage plants are able<br />

to abate toxic levels of air-borne pollutants in<br />

building interiors.<br />

<strong>The</strong> esthetic and psychological enhancement of<br />

interior environments and purification of indoor<br />

air have become catalysts in promoting foliage<br />

plant production and increasing their wholesale<br />

value. For instance, the wholesale value of<br />

foliage plants in the United States (U.S.) increased<br />

from $13 million in 1949 to $663 million in<br />

2002, which was a 51-fold increase in 53 years.<br />

With increasing worldwide urbanization and an<br />

innate desire for naturalistic environments<br />

within our building interiors, foliage plant production<br />

and utilization have become a truly globalized<br />

industry. Propagation, production, and<br />

interior use of foliage plants as well as plant<br />

related transportation, retail sales, and services<br />

contribute significantly to the world economy<br />

and our sense of well-being.<br />

FOLIAGE PLANT ORIGINS<br />

Most foliage plants are native to the world’s<br />

tropical or subtropical regions. It is estimated<br />

that plants from more than 100 genera and at<br />

least 1,000 species have been and can be<br />

grown as foliage plants (Chen et al., 2005).<br />

Important genera of foliage plants indigenous<br />

to tropical Africa include Aloe, Asparagus,<br />

Chlorophytum, Chrysalidocarpus, Coffea,<br />

Crassula, Cyanotis, Dracaena, Haworthia,<br />

Hypoestes, Kalanchoe, Leea, Pandanus,<br />

Saintpaulia, Sansevieria, Senecio, Strelitzia, and<br />

Zamioculcas. Asia is the origin of Aeschynathus,<br />

Aglaonema, Alocasia, Aspidistra, Asplenium,<br />

Aucuba, Begonia, Chlorophytum, Codiaeum,<br />

Coleus, Cordyline, Epipremnum, Fatsia, Ficus,<br />

Gynura, Homalomena, Hoya, Phoenix,<br />

Pittosporum, Polyscias, Sansevieria, Schefflera,<br />

and Spathiphyllum. <strong>The</strong> distinction of foliage<br />

plant origin between Australia-Oceania and<br />

Southeast Asia is difficult. It is generally believed<br />

that Araucaria, Asplenium, Blechnum,<br />

Cissus, Cordyline, Dizygotheca, Howea,<br />

Platycerium, Polyscias, and Schefflera are largely<br />

native to the Australia-Oceania region. <strong>The</strong><br />

warm and humid climate of South and Central<br />

America nurtures diverse foliage plants including<br />

Adiantum, Aechmea, Anthurium, Ananas,<br />

Aphelandra, Billbergia, Calathea, Chamaedorea,<br />

Dieffenbachia, Episcia, Fittonia,<br />

Guzmania, Maranta, Monstera, Neoregelia,<br />

Nephrolepis, Nidularium, Nolina, Peperomia,<br />

Philodendron, Pilea, Polypodium, Ruellia,<br />

Senecio, Spathiphyllum, Stromanthe, Syngonium,<br />

Tillandsia, Vriesea, Yucca, and Zebrina. A<br />

few foliage plants, chiefly Agave, Peperomia,<br />

Yucca, and some Bromeliaceae and Cactaceae<br />

genera, are native to North America. Hedera is<br />

probably the only important foliage plant genus<br />

indigenous to Europe.<br />

<strong>Foliage</strong> plants that are native to tropical regions<br />

are generally tolerant of low light intensities,<br />

sensitive to chilling temperatures, and day-neutral<br />

to photoperiod since they grow either as<br />

understory plants shaded by giant forest trees<br />

or as vines climbing on trees. In subtropical<br />

climates, both temperatures and humidity may<br />

vary with the seasons; foliage plants originating<br />

in this climate tolerate limited degrees of heat,<br />

drought, and chilling temperatures and may<br />

also show dormancy in winter. Some plants<br />

used indoors are native to climatically extreme<br />

conditions, such as deserts, and have evolved<br />

mechanisms to adapt to heat and drought<br />

stresses. <strong>The</strong>se plants, predominately succulents<br />

and cacti, often have unique leaves or distinctive<br />

shapes and/or flowers.<br />

A BRIEF HISTORY<br />

<strong>The</strong> Sumerians and ancient Egyptians started<br />

growing plants in containers about 3,500 years<br />

ago, and writings on ornamental cultivation of<br />

container plants in Chinese date back to 3,000<br />

Figure 3. <strong>Foliage</strong> plants used as landscape<br />

plants in the tropics with<br />

Philodendron bipinnatifidum planting<br />

and Epipremnum aureum vine.<br />

ISHS • 10

Figure 4. Wardian case invented by Dr.<br />

Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward in 1833 used for<br />

shipping collected tropical plants to<br />

Britain.<br />

Figure 5. Dieffenbachia x Bausei was a hybrid selected from a cross between D. maculata<br />

and D. weirii in 1870 (A) and D. x Memoria-corsii was a hybrid developed from a cross of D.<br />

maculata and D. wallisii made in 1881 (B).<br />

to 4,000 years ago. However, there is no<br />

known record as to precisely when humans first<br />

started to use foliage plants for interior decoration.<br />

A likely scenario for the early use of foliage<br />

plants could be that these plants were initially<br />

collected as curiosities due to their varied<br />

forms, styles, colors, and textures; when used<br />

to esthetically enhance building interiors, they<br />

actually survived for extended time periods.<br />

Although the definitive beginnings of interior<br />

plant use is not clear, it is known that during<br />

the Renaissance, plant collectors in Holland and<br />

Belgium imported plants from Asia Minor and<br />

the East Indies, and wealthy merchants of<br />

Florence, Genoa, and Venice introduced plants<br />

from the East into Europe in the late 15th century<br />

(Smith and Scarborough, 1981). A desire<br />

for exotic plants developed among the aristocracy<br />

of France and England by the middle of<br />

the 16th century, and orangeries and conservatories<br />

became commonplace on the estates of<br />

the nobility and wealthy class by the 17th century.<br />

By the following century, an estimated<br />

5,000 species of exotic plants had been<br />

brought into Europe from the world’s tropics.<br />

<strong>The</strong> number of plants brought to Europe from<br />

the tropics increased after the invention of the<br />

Wardian case in 1833 (Fig. 4). <strong>The</strong> protected<br />

environment of the Wardian case dramatically<br />

increased the number of living specimens that<br />

survived the long sailing voyage from the<br />

tropics to Europe. <strong>The</strong> availability of diverse and<br />

exotic plants that could tolerate the environment<br />

typical of Victorian homes promoted the<br />

use of living plants indoors and gave birth to<br />

the modern foliage plant industry. During the<br />

second half of the 19th century, foliage plants<br />

became a symbol of social status, and the<br />

grand drawing rooms of Victorian houses all<br />

had their fill of palms and ferns. <strong>Plant</strong>s from<br />

conservatories, botanical gardens, and private<br />

estates were brought into commercial production,<br />

and bought for use in middle- and upperclass<br />

households. Hybridization of Dieffenbachia<br />

species dates to almost the same time<br />

period as hybridization of peas by Gregor<br />

Mendel. <strong>The</strong> oldest known Dieffenbachia<br />

hybrid is ‘Bausei’, a cross between D. maculata<br />

and D. weirii made in 1870 in the greenhouses<br />

of the Royal Horticultural Society of London at<br />

Chriswick, while ‘Memoria-corsii’ is a cross<br />

between D. maculata and D. wallisii made in<br />

1881. Both are still in cultivation in the industry<br />

(Fig. 5). Within a decade, shiploads of foliage<br />

plants from greenhouses in England and mainland<br />

Europe were sold to greenhouse growers<br />

in the Northeast U.S. for either immediate<br />

resale or for “growing on” and subsequent<br />

resale. <strong>The</strong>se shipments may be considered as<br />

the beginning of globalization of foliage plant<br />

production.<br />

PROPAGATIVE MATERIALS<br />

<strong>The</strong> majority of propagative materials used in<br />

the industry are cuttings and tissue culture<br />

Figure 6. Tissue culture facilities in Sunshine Horticulture LLC., Quanzhou, Fujian Province,<br />

China: (A) culture room, (B) employees transferring culture, (C) tissue culture plantlets shipped<br />

to the U.S., (D) liners grown in shaded greenhouses.<br />

CHRONICA HORTICULTURAE •VOL 45 • NUMBER 4 • 2005 • 11

Figure 7. Stock plant and cutting production in Central America: (A) Dieffenbachia production<br />

in Honduras and (B) Sansevieria trifasciata divisions arriving in the U.S. from Costa Rica.<br />

liners, with seeds used for just a few selected<br />

genera. Currently, there are four main regions<br />

of foliage plant propagule production: Asia,<br />

Central and South America, the European<br />

Union (E.U.), and the U.S.<br />

Asia is a region predominately providing massive<br />

numbers of tissue culture plantlets (Fig. 6).<br />

Dongguan Agristar Biotechnoloy Co., Ltd.,<br />

Guangdong Province, China, produces 20 million<br />

tissue culture plantlets of foliage plants,<br />

including Aglaonema, Alocasia, Anthurium,<br />

Calathea, Cordyline, Dieffenbachia, Dracaena,<br />

Ficus, and Syngonium as well as various<br />

Bromeliads, ferns, and Musa species. Almost all<br />

these plantlets are exported to Australia, E.U.,<br />

and Southeast Asia. Sunshine Horticulture LLC.,<br />

Quanzhou, Fujian Province, China exports 68%<br />

of its tissue culture plantlets of Anthurium,<br />

Alocasia, Ficus, Spathiphyllum, and bare rooted<br />

‘Lucky Bamboo’ (Dracaena sanderiana) and<br />

‘Money Tree’ (Pachira macrocarpa) to the U.S.<br />

Other countries involved in tissue culture plantlet<br />

production include India, Singapore, Sri<br />

Lanka, and Thailand. Commercial tissue culture<br />

firms in India export more than 40 million tissue<br />

culture plantlets to the U.S. and other countries<br />

(Govil and Gupta, 1997).<br />

Many foliage plant species are native to Central<br />

and South America, and commercial nurseries<br />

are mainly located in Brazil, Colombia, Costa<br />

Rica, Guatemala, and Honduras. Climatic conditions<br />

are favorable for extensive stock bed<br />

plantings to produce vast numbers of<br />

Aglaonema, Codiaeum, Cordyline, Dieffenbachia,<br />

Epipremnum, Dracaena, Peperomia,<br />

Philodendron, Sansevieria, and Schefflera cuttings<br />

which are exported to the U.S., E.U., and<br />

several Asian countries (Fig. 7). According to<br />

the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, the<br />

wholesale value of unrooted foliage plant cuttings<br />

imported from Central and South America<br />

to the U.S. was $29 million in 2002.<br />

Although there are few foliage plants native to<br />

Europe, the collections made during 17th to<br />

19th centuries provided diverse germplasm for<br />

propagation and production. <strong>The</strong> Netherlands<br />

emerged as the predominant European country<br />

for foliage plant propagation during the 20th<br />

century. For example, Anthura B.V. in Bleiswijk<br />

has developed an extensive breeding program<br />

and uses modern facilities for Anthurium,<br />

Bromeliad, and Palaenopsis propagation.<br />

Uniform and healthy propagative materials are<br />

exported to other European countries, China,<br />

Japan, Australia, and the U.S. Several nurseries<br />

in the Netherlands produce hybrid seeds of<br />

Spathiphyllum cultivars sold to other European<br />

countries and the U.S.<br />

In the continental U.S., large nurseries in<br />

California and Texas produce numerous foliage<br />

plant propagules, but the greatest numbers are<br />

produced in Central Florida, primarily in the vicinity<br />

of Apopka, Florida, often considered the<br />

indoor foliage capital of the world (Fig. 8).<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are more than 900 certified nurseries,<br />

largely for foliage plants, clustered in Apopka<br />

vicinity. Agri-Starts, Inc. and Twyford <strong>Plant</strong><br />

Laboratories, Inc., in the Apopka area, and<br />

Oglesby <strong>Plant</strong> International, Inc., in Altha,<br />

Florida, have an annual production capacity of<br />

more than 50 million tissue culture liners of<br />

various foliage plants including Alocasia,<br />

Anthurium, Calathea, Dieffenbachia, Ficus,<br />

Musa, Philodendron, Syngonium, Spathiphyllum,<br />

and different species of ferns and<br />

Bromeliads. In addition to meeting the needs of<br />

foliage plant producers in Florida and other states,<br />

tissue culture liners are also exported to<br />

Canada, E.U., and Asian countries. Hawaii with<br />

its tropical climate produces propagative materials<br />

of Anthurium, orchids, and Dracaena cuttings<br />

and sells to the U.S. mainland, Japan, and<br />

E.U. markets.<br />

FOLIAGE PLANT<br />

PRODUCTION<br />

<strong>The</strong> E.U.<br />

Commercial production of foliage plants started<br />

in Europe and was based on the extensive collection<br />

of foliage plants made during the 17th<br />

to 19th centuries. <strong>The</strong> availability of foliage<br />

plants capable of surviving extended periods<br />

indoors promoted the widespread use of living<br />

plants for interior decoration. <strong>The</strong> demand for<br />

plants provided the stimulus for construction of<br />

commercial greenhouses to supply this burgeoning<br />

market. As production output increased,<br />

additional markets were sought and large shipments<br />

of foliage plants were sent to the U.S. in<br />

Figure 8. Indoor foliage capital of the world, Apopka, Florida: (A) city of Apopka slogan and (B) fern statue commemorating Boston Fern<br />

(Nephrolepis exaltata) that started foliage plant production in Apopka, Florida.<br />

ISHS • 12

Figure 9. <strong>Foliage</strong> plant production and trading in the Netherlands: (A) Dutch greenhouse<br />

production of foliage plants, (B) Anthurium production, (C) Aalsmer auction building, and<br />

(D) auction of plants.<br />

about 14% of the Netherlands’ foliage plants<br />

were imported, of which India, Italy, and<br />

Germany accounted for 26%, 14%, and 14%,<br />

respectively, in 2000 (EU Market Survey, 2002).<br />

A great part of the Netherlands’ imports was<br />

re-exported to other countries. <strong>The</strong><br />

Netherlands exported about 21%, 22%, and<br />

52% to Germany, United Kingdom, and<br />

France, respectively. Although there is no data<br />

available for foliage plants per se, the<br />

Netherlands’ auctions now handle 89% of the<br />

Netherlands’ production and 80% of imported<br />

floricultural crops including foliage plants with<br />

a total value of US $3.0 billion in 2001 (EU<br />

Market Survey, 2002).<br />

the late 19th and early 20th century. <strong>The</strong> E.U. is<br />

still a major region of foliage plant production.<br />

In addition to the Netherlands, Belgium,<br />

England, France, Germany, and Italy are significant<br />

producers of foliage plants for the<br />

European and international markets (Fig. 9).<br />

Almost all foliage plants produced in the E.U.<br />

are sold through a wholesaler or auction<br />

houses. <strong>The</strong> floriculture auction houses in the<br />

Netherlands play a crucial role in the trade of<br />

foliage plants. Through their concentration of<br />

supply and demand, they act as a price-setting<br />

mechanism for the trade and have developed<br />

into a major center for the distribution of<br />

domestic and foreign grown products to the<br />

markets of the E.U. Major foliage plants in<br />

Dutch auctions include Anthurium, Dracaena,<br />

Ficus, Hedera, Saintpaulia, Phalaenopsis,<br />

Howea, as well as ferns and Bromeliads. In<br />

addition to plants from domestic production,<br />

Figure 10. <strong>Foliage</strong> plant production in the U.S.: (A) Dieffenbachia and Epipremnum production<br />

in shaded greenhouse in Apopka vicinity, Florida, (B) Anthurium production in Dade<br />

county, Miami area, Florida, (C) Tropical plant industry exhibit (TPIE) in Ft. Lauderdale,<br />

Florida, and (D) interior of TPIE in 2003.<br />

<strong>The</strong> U.S.<br />

<strong>The</strong> resale or planting of foliage plants shipped<br />

from Europe to the Northeast U.S. in the 19th<br />

century were the beginning of the foliage plant<br />

industry in the U.S. Because of favorable climatic<br />

conditions, large scale production of foliage<br />

plants moved to California and Florida within<br />

the first two decades of the 20th century.<br />

Predominant plants grown in California during<br />

the 1920s include Kentia palm (Howea forsterana)<br />

and Pothos (Epipremnum aureum), followed<br />

by Philodendron and Araucaria in the<br />

1940s. Production in Central Florida was confined<br />

to Boston Fern (Nephrolepis exaltata) from<br />

1912 to 1928 until Heart-leaf Philodendron<br />

(Philodendron scandens oxycardium) was introduced.<br />

<strong>The</strong> primary foliage plants grown in<br />

South Florida during the same time period were<br />

Snake <strong>Plant</strong> (Sanservieria trifasciata) and Screw<br />

Pine (Pandanus veitchii). During the 1930s,<br />

Chinese Evergreen (Aglaonema modestum),<br />

Rubber <strong>Plant</strong> (Ficus elastica), and Oval-leaf<br />

Peperomia (Peperomia obtusifolia) became<br />

widely grown in Florida (Smith and<br />

Scarborough, 1981). Florida produced $1.8 million<br />

of the national foliage plant wholesale<br />

value of $13 million in 1949. However, 10 years<br />

later, Florida supplanted California as the leading<br />

state in the nation in production of foliage<br />

plants, and has accounted for more than 55%<br />

of the national wholesale value since the 1960s.<br />

<strong>Foliage</strong> plant wholesale value in Florida increased<br />

from $1.8 million in 1949 to $459 million in<br />

2002, which was a 255-fold increase. Other<br />

important U.S. foliage plant producing states<br />

include Hawaii and Texas. <strong>Foliage</strong> plant marketing<br />

in the U.S. is through trade show contacts<br />

and direct sales to mass merchandisers, mainly<br />

super markets, wholesale stores, and interior<br />

plantscape firms. One of the most important<br />

trade shows is the Tropical <strong>Plant</strong> <strong>Industry</strong><br />

Exhibition (TPIE), organized by the Florida<br />

Nursery, Growers, and Landscape Association<br />

(Fig. 10) and held every January in Ft.<br />

Lauderdale, Florida. <strong>The</strong> TPIE features booths filled<br />

with living and vibrant plants creating a virtual<br />

indoor garden. Other booths display a multitude<br />

of products necessary for production and<br />

utilization of foliage plants. With more than<br />

500 exhibiting companies from different coun-<br />

CHRONICA HORTICULTURAE •VOL 45 • NUMBER 4 • 2005 • 13

tries, TPIE offers wholesale buyers an extensive<br />

selection of foliage plants and associated products<br />

in one location.<br />

Asia<br />

Many foliage plants are associated with good<br />

luck or fortune in Asian culture; for example,<br />

Aglaonema is believed to bring good fortune to<br />

life, Dracaena sanderiana is called Lucky<br />

Bamboo, and Pachira macrocarpa is known as<br />

the Money Tree. However, commercial production<br />

of foliage plants in Asia is a more recent<br />

trend. An accidental discovery of Aglaonema<br />

alumina armandi on a mountain in the province<br />

of Rizal on Luzon Island of the Philippines in<br />

1976 sparked a large scale search for new species<br />

in Southeast Asia. New Aglaonema species<br />

were found in Thailand in the south along the<br />

Malaysian border and in the west along the<br />

border with Burma. New species not only enriched<br />

the gene pool of Aglaonema, but also led<br />

to the establishment of active breeding programs<br />

in Thailand, Philippines, and India. In the<br />

early 1980s, Sithiporn Donavanik of Thailand<br />

successfully crossed A. rotundum with A.<br />

marantifolum ‘Tricolor’ resulting in a cultivar<br />

with colors so vibrant in shades of red that the<br />

plant strongly resembles a Codiaeum variegatum.<br />

In Thailand, this new cultivar was named<br />

A. sithiporn. Twyford <strong>Plant</strong> Laboratories, Inc., of<br />

Apopka, Florida, procured several plants of A.<br />

sithiporn’s new hybrids in 1998. Sunshine<br />

<strong>Foliage</strong> <strong>World</strong>, Zolfo Springs, Florida, introduced<br />

more than 30 new Aglaonema hybrid cultivars<br />

developed by breeders in Thailand. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

cultivars have different leaf sizes, shapes, and<br />

variegation patterns, and white, green, or pink<br />

petioles. ‘Emerald Star’ and ‘Jewel of India’ are<br />

two cultivars developed by breeders in India<br />

that, along with ‘Stars’, have been identified as<br />

highly tolerant to chilling temperatures (Chen et<br />

al., 2001). Cacti are a unique group of foliage<br />

plants. <strong>The</strong>re are about 15 million grafted cacti<br />

sold yearly in the international market, of which<br />

Korea produces 10 million (Jeong et al., 2004).<br />

Other foliage plant genera produced in Asian<br />

countries include Aglaonema, Anthurium,<br />

Calathea, Ficus, Phalaenopsis, Bromeliads, and<br />

ornamental gingers as well as braided Lucky<br />

Bamboo (Dracaena sanderiana), Money Tree<br />

(Pachira macrocarpa), Buddha’s Hand (Alocasia<br />

cucullata), and Ginseng Fig (Ficus macrocarpa).<br />

Much of this production is exported to other<br />

countries including the U.S. In 2000, the values<br />