Written By Tom Gable

Another spring has arrived and with it the birth of wolf pups for wolf packs in and around Voyageurs National Park. Most pups are born in the first 3 weeks of April and we know that at least 3 packs have given birth already based on the movements of GPS-collared wolves in those packs and we suspect another pack to show indications of this any day now.

One of our fundamental research objectives on the Voyageurs Wolf Project is to learn as much as we can about the pup-rearing behavior of wolves. For example, how many pups are born each year? Where are wolves giving birth to and rearing pups? How many pups survive to adulthood?

Wolf pups from the Bluebird Lake Pack in Spring 2022 taken shortly after we removed the pups from the den. Once pups are removed from dens, we briefly put them in a sack with their littermates where the pups wait until we can tag them. We put the pups back into the den once we are done tagging them. Photo: Anthony Souffle

Answering these questions requires having GPS-collared wolves in packs so that we can determine where dens are. The more packs that have collared wolves in them, the more data we are able to glean. We had collared wolves in 8 different packs last fall and were excited because that seemed to indicate we would be able to study the pup-rearing behavior of a substantial number of packs this spring.

But we should have known better. Wolves live dynamic, perilous lives that are unpredictable and ever-changing. We have observed evidence of this every year—collared wolves that we thought would live ended up dying, wolves that we thought would stay with their pack ended up leaving. Yet, we still hoped this winter would be different.

The wolves had other plans.

In October 2022, both collared wolves from the Wiyapka Lake Pack left the pack and dispersed. One wolf is currently on the shores of Lake Vermillion and the other in north-central Wisconsin! Both are still lone wolves, presumably wandering in search of a mate and a place to settle down.

A few months later, both collared wolves in the Bluebird Lake Pack, which was only 3 wolves to begin with, were killed by other wolves within a 1-week period in late January. The collared wolves were the breeding male and female of the pack, and once they were killed, the pack was effectively ended. Their territory was promptly taken over by a new pack that we named the “Clearcut Pack”.

How we found the breeding male of the Bluebird Lake Pack in late January 2023. The breeding male had been killed by other wolves just 6 days after his mate was also killed by other wolves. This male’s death marked the end of the Bluebird Lake Pack.

At the same time, Wolf Y1T, the breeding male of the Blood Moon Pack, started wandering south of his territory with his mate—the pack is only these two wolves. The pair spent most of the winter rambling around the remote country between Nett and Ash Lake and have yet to return to their territory for good. We are not sure why yet.

Then in March, we lost contact with the Lightfoot Pack. One collared wolf in the Lightfoot Pack decided to hit the open road and head north to Canada. About the same time, the collar on the only other collared wolf in the pack stopped working—an unfortunate technological failure!

All said and done, in a matter of 6 months, we went from 8 packs with collared wolves to 4. As I alluded to earlier, this pattern is not entirely unusual for us but we are always optimistic we might get lucky. However, this highlights why studying wolves in densely-forested environments can be so challenging and difficult.

We will start trying to collar wolves in late April and early May. If we have a good start, like we did last year, we might be able to get functional collars on several other packs before the end of May. We typically aim to collar 1-2 wolves in the majority of packs we study. And while that rarely happens, it is what we aspire to.

Regardless, we are excited to study the pup-rearing behavior of the 4 packs that do have GPS-collared wolves in. During the first two weeks of May, we will visit the dens of each of these packs to count the number of pups and to tag each pup. To do this, we briefly remove pups from dens so that we can sex pups, take measurements, collect genetic samples, and insert small micro-chips that will allow us to identify pups as adults.

A wolf pup from the Windsong Pack in Spring 2022. Five pups from the Windsong Pack survived to their first birthday, which is quite extraordinary for wolves in the Voyageurs area. Photo taken by Anthony Souffle.

This information is critical to answering the most important question regarding wolf pups: how many survive their first year? For over 50 years, biologists studying wolves in forested ecosystems have wondered about pup survival rates yet studying pup survival in ecosystems where you cannot readily observe wolf pups had made this challenging. As a result, some have stated that wolf pup survival is “probably the single greatest enigma in wolf biology today”.

Yet, recent technological advances have provided new tools to estimate wolf pup survival rates in forested ecosystems and we on the Voyageurs Wolf Project are using all of these new tools in a concerted effort to reveal this aspect of wolf biology that has remained poorly understood.

Our main approach is to count the number of pups in dens so we know how many are born, which is crucial for determining what percent actually survive. We then use remote cameras scattered about pack territories to get video footage of pups as they get older to determine how many pups are still alive as summer progresses to fall and then winter.

A Windsong pup in the pack’s den in Spring 2022. The den was just a dug out area underneath the roots of a conifer. Photo: Anthony Souffle.

So far, we have found some interesting results: pup survival from year to year appears highly variable. For example, we estimated that only 7% of pups survived till their first birthday in 2020-2021. That stands in stark contrast to the following year (2021-2022) when 53% of pups survived to adulthood.

For context, the typical litter in the Voyageurs area consists of 5.1 pups based on data from 29 litters. Thus, in 2020-2021, an average of only 0.4 pups per pack survived compared to 2.7 pups per pack just one year later. Such variation in survival rates is fascinating and intriguing, or at least we think so. How could survival change so drastically from one year to the next? We have some strong suspicions but do not know for sure yet. Ultimately, we need several more years of data to have a large enough sample size to examine this topic robustly because there are a lot of variables to account for and we only add a few data points each year!

But, we are optimistic that we will be able to understand what drives wolf pup survival, and in turn wolf population change, if we can keep the Voyageurs Wolf Project going long-term, which is our dream!

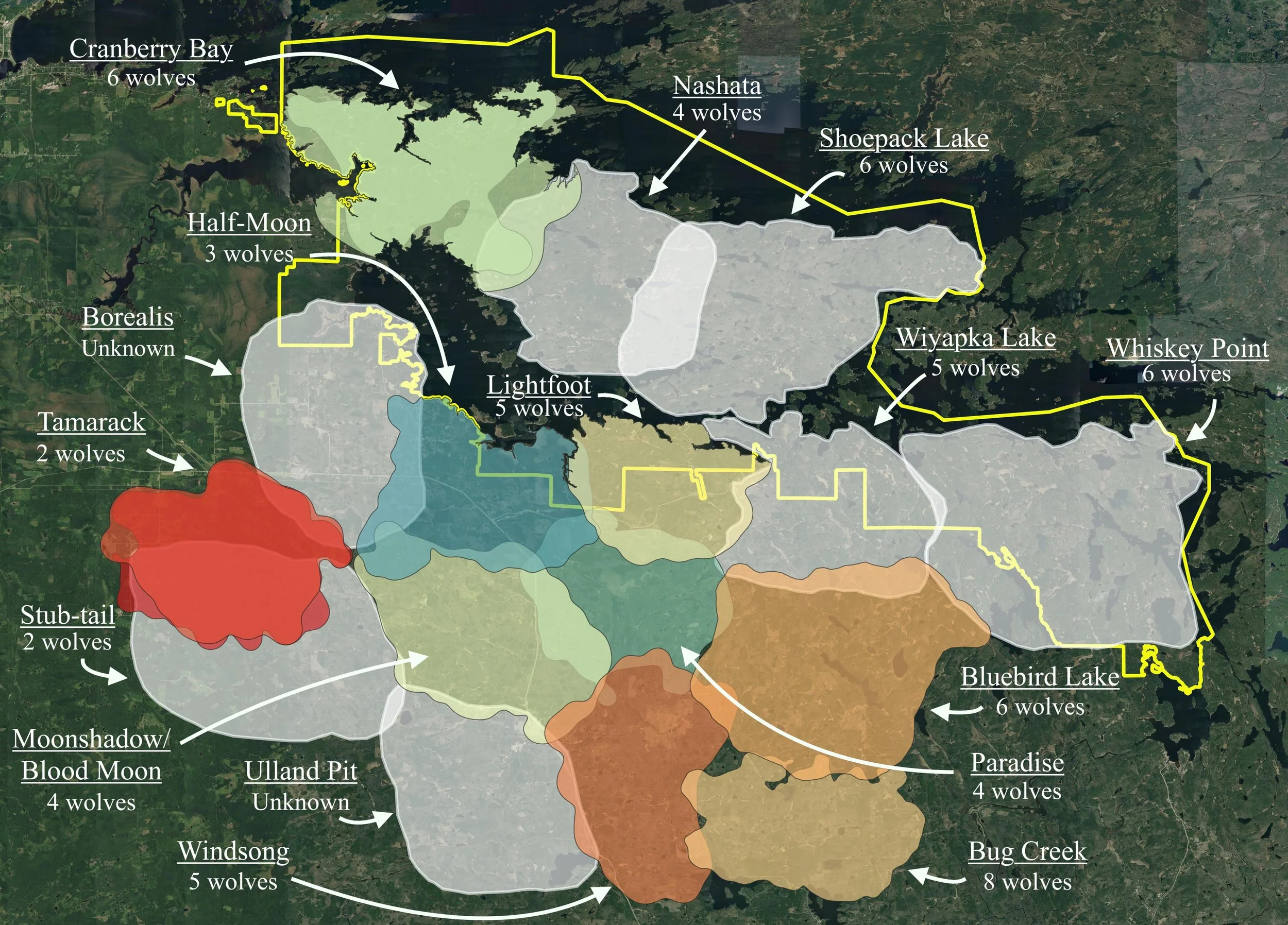

Wolf pack territories in and around Voyageurs National Park. The number below each pack refers to the number of wolves in each pack in Winter 2021-2022. We will share updated information for 2022-2023 this summer! We currently have wolves collared in the Paradise, Bug Creek, Windsong, and Vermilion River Pack. The Vermilion River pack is not on this map but is just to the east of the Bug Creek Pack.