Who’s looking out for Swope Park?

There’s a secret forest inside the Kansas City Zoo, which itself sits inside Swope Park, the largest and most visited park in the city. Here, beyond a ten-foot-high fence with a locked gate, the voices at the zoo and the sounds of trains fall away. You hear the songs of warblers and mockingbirds and the wind in the tall trees — bur oaks, sycamores, and black walnuts, some of them 200 years old — that soar in the sky above native grasses, paw paw trees, and wild ginger.

This is Shirling Sanctuary. According to Linda Lehrbaum of KC WildLands — a group that has, along with members of the Burroughs Audubon Society, resuscitated the area — we’re standing in a highly biodiverse remnant riparian forest. Another way of saying that: it’s a rare, old-growth river bottom forest that was never tilled or otherwise modified. The forest here is the same forest Lewis and Clark saw as they hiked westward through Kansas City. It’s stunning.

But Shirling Sanctuary — and Rocky Point Glade, another remnant area resurrected and managed by KC WildLands — is very much the exception to the rule when it comes to Swope Park care and preservation. Swope has hundreds of acres of forested land, much of it under constant assault by destructive invasive species. That includes plants like honeysuckle. But it also includes the humans who have sought, repeatedly and successfully over the years, to develop the park for their own ends. Throw into the mix a chronically underfunded parks budget, and a tough question comes into focus: Does Kansas City really care about preserving this park?

There is so much to do at Swope Park.

Amenities include the Zoo, Starlight Theatre, Swope Park Pool, two golf courses, Lakeside Nature Center, fishing at Lake of the Woods, a zipline adventure company, and more than 13 miles of mountain biking trails. Relatively recently, the Swope Soccer Village and Sporting KC Training Facility added nine fields dedicated to play and training. Later this year, KC Pet Project will open its massive (and much-needed) $26 million Campus for Animal Care on park ground near Elmwood and Gregory streets.

“It’s the primary [Parks] location with the greatest opportunity for us to connect as a community,” says Teresa “Terry” Rynard, the recently appointed director of Kansas City Parks and Rec.

Few would argue. But beneath these positive civic developments is a park whose critical needs are not being met, with no resolution in sight.

If you were to visit Swope Park 100 years ago, you would most likely have arrived in a packed streetcar at the Grand Entrance near Meyer Boulevard and Swope Parkway. You’d have seen the stately limestone Shelter Number 1 (now the Swope Interpretive Center) with the flowering formal Eib Gardens behind it, immaculately manicured in the style of a meticulous English garden. To the northeast, visitors could stroll to the zoo or the large lagoon for a boat ride. In the distance, beyond fields where horses grazed and rested, and where Kansas Citians picnicked, you’d have seen the impressive white granite Thomas H. Swope Memorial, built in honor of the local real estate magnate who gifted the city 1,332 acres of land to be “used as a Public Pleasure Ground or a Park Forever.” The park soon expanded to over 1,800 acres, and was — still is — one of the largest urban parks in the world. Swope Park was envied across the Midwest as a naturalist treasure, a crown jewel of Kansas City.

Despite the raw beauty of Shirling Sanctuary and Rocky Point Glade, a century later you are unlikely to find many Kansas Citians who view Swope Park with such awe. The Delbert J. Haff Mirror Fountain, just west of the Grand Entrance, recently received an impressive $1.2 million renovation through a public-private fundraising effort, but Shelter Number 1, just a few hundred feet away (and perhaps the park’s most historically significant building) now sits essentially empty, closed to the public save for one office that’s rented to a Blue River conservation group. Other historic buildings, from the Lakeside ranger station to the former summer camp buildings, are empty and have fallen into disrepair. The Eib Garden sits fallow; you won’t find the seasonal flowers and plants common to the beds in Loose Park and along Ward Parkway. It is rare to see people walk through the gardens. Few seem to even notice the nearly 200-foot-high flagpole built by Jacob Loose — the tallest in the world when it was erected.

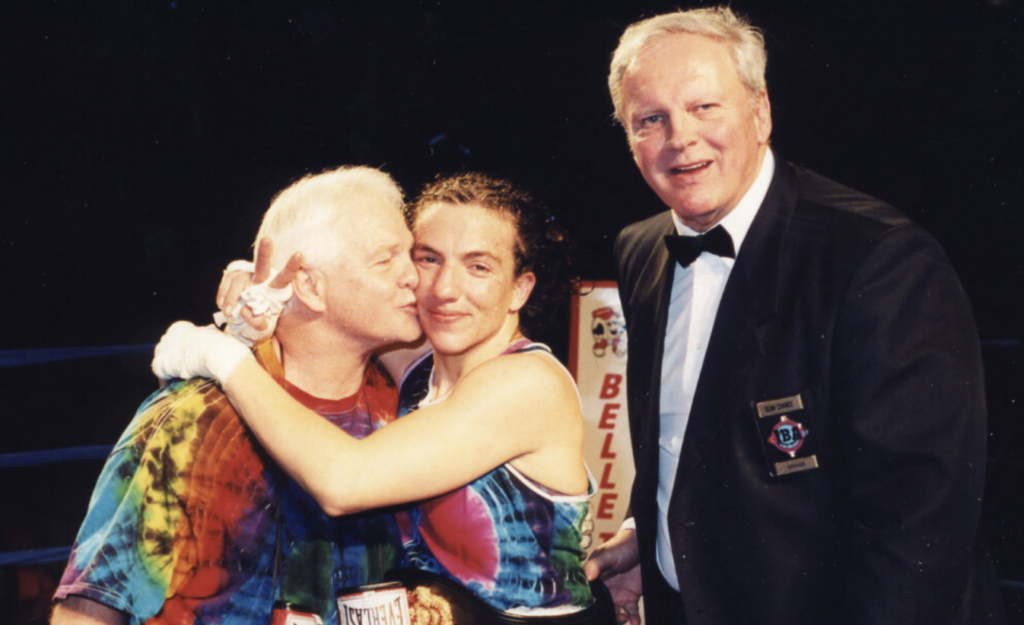

Beyond the gardens, the grassy fields between the entrance and the zoo are kept clipped but are in many spots patchy, barren, or weedy. Dozens of times a year, these fields double as parking lots for Starlight shows. The carved lions at Thomas Swope’s memorial (pictured above) still stand proud. But in May, a large tree felled by a spring storm blocked ramp access to the memorial for weeks before it was removed.

Both Rynard and Todd Garrett, who oversees maintenance for Swope Park, are sensitive to, and readily acknowledge, the reality that beautification and maintenance efforts at Swope don’t measure up to some of the city’s other parks.

Garrett says he and his crew devote almost everything they have simply to maintaining the status quo. Turf rebuilding — counteracting the damage that occurs when people drive vehicles directly up to shelters during barbecues and other gatherings — is a constant and never-ending task at the park. Dumping is also an issue, as is cleaning up scattered trash. Currently, the two full-time employees whose job it is to clean up refuse at Swope haul out a truckload of trash a day. “And this isn’t a small truck, either,” Garrett says.

Rynard and Garrett don’t say it this way exactly, but it all boils down to the age-old hard truth that Money Talks. If rich people wanted to fund beautification efforts at Swope Park, they could. But they’re not.

“Right now, Swope is mowed on the same schedule as every other park in the city,” says Rynard. “The exceptions [in beautification] are the areas that are enhanced by private donors, like Loose Park. I don’t love that it’s our process … but we do lack resources.”

Larry Rizzo, a biologist and conservationist who regularly works with KC WildLands, is more blunt.

“There is a big racial component to this,” he says. “There has been this perception that Swope is dangerous. It’s black.”

Rizzo recalls how, a few years ago, a tall tree fell on Shelter 7 after a storm, rendering the structure unusable. It remained that way for several weeks, even though it was the middle of the summer — a prime usage time for the shelter. “That would never happen at Loose Park,” Rizzo says.

What is good for the city — a new animal shelter, soccer fields, a lovely amphitheater — is often bad for the park, or at least for those who view a park through a traditional, naturalist lens. Development began claiming wild park land in the 1930s, when Swope Memorial Golf Course was built. Then came Starlight and a zoo expansion. KC Pet Project will utilize dozens of acres of formerly forested land for its 60,000-square-foot campus.

Rynard says she considers many of the above developments to be worthy tradeoffs.

“In these cases, we had good mission alignment, and conservation partnerships were good with [it],” she says. “We were approached, and I would say we embraced, for a lack of a better term, the idea of bringing new patrons into the park and enhancing the usability. I would say that the loss of forested area was examined in the cost/benefit.” Rynard also points to a citywide tree-planting effort and the adoption of a new sustainability plan for the Parks system as indicators that conservation is not far from the minds of those in the Parks Department.

Lehrbaum, the KC WildLands program director who took me through Shirling Sanctuary, says she understands that the Parks Department has to balance stakeholder wants and needs when it comes to park lands.

But, she says pointedly, “Once this land is gone, it’s gone. Even the sites that are degraded [by invasive species] are just as important as the other sites for maintaining the functionality of our natural ecosystem, air quality, soil quality and flood control.”

Swope — a huge green space with a healthy, forested river habitat — is also a major home for native birds and hundreds of other species of migrating birds. Elizabeth Stoakes from the Burroughs Audubon Society says that dozens of varieties of warblers and scarlet tanigers (which are prized by birders) stop for food and rest in the park on their way from South America to Canada. Orioles, nuthatches, and flycatchers, too. “I do get concerned,” Stoakes says regarding development within the park. “Swope Park is one of the nicest pieces of urban forest that we have, and it’s been with us a long time.”

Invasive plant species in the park — winter creeper and honeysuckle, mostly — pose the gravest threat to Swope’s future, though. Groups like KC WildLands (with some financial assistance and the blessing of Parks and Recreation), expend continuous effort in battling back these species in places like the Shirling Sanctuary and Rocky Point Glade. But money’s tight, and almost all the work is done by volunteers, so the fight is sporadic.

“Winter creeper is at Shirling Sanctuary,” Lehrbaum says. “Eventually it gets up into the trees and produces fruit. Winter creeper and honeysuckle choke off the native trees. Once those trees die, they can’t come back. We are looking at the destruction of our entire natural forest. Even the areas we don’t consider super high-quality still serve a very important purpose to our local ecosystem.” Lehrbaum says she believes the Parks system is aware of the problem and wants to do something about it. But from her vantage point, it’s far from a top Parks priority.

Ultimately, for Swope Park to thrive again, the city will have to step in and invest significantly in its future. In addition to a lack of funds for beautification, the Parks Department has a $65 million deferred maintenance problem. Much of this relates to Swope, where the historic shelters, stone picnic tables, flower beds, and many of the roads are in need of attention. There are also accessibility issues for disabled patrons that have yet to be reckoned with. Rynard sees potential in reaching out to massive national funding organizations that promote public health, like the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Surrounding Swope Park is KC’s East Side, where life expectancies are lower and health outcomes are poorer than in the rest of the city. An improved Swope might help ameliorate some of these issues.

“I’ve worked in every district that we have — I’m very familiar with all areas of the city,” Garrett says, his voice rising a bit. “I just want the people that live in this area and everywhere to know that we are doing our best with the resources that we have to try to maintain this park up to a high standard like Loose Park and Roanoke Park. It only takes more people that love the area, and love the park, to get involved.”

♦♦♦

Four Things You (Probably) Didn’t Know About Swope Park

1. Thomas Swope wanted his park to help the beneficiaries of the Humane Society — which at the time meant horses and children. Thomas Swope had a soft spot for Kansas City’s horses, which in the early 1900s were everyday work animals. Swope was concerned about the horses’ lack of resting time, fresh food, and fresh air, and he wanted the park to be a place where not just people but horses could recreate. Swope also cared a great deal about children, encouraging programs that benefited particularly impoverished and disabled children. This legacy carried forward in form of summer camps that ran until the 1960s in the Lake of the Woods area and near where the Go Ape Ziplining Adventure campus now sits. Some of those old camp buildings are still used by Parks staff, though others sit empty and in disrepair. Last summer, artist Ebony Patterson used a long-abandoned therapy pool for her popular exhibit “Called Up,” painting the pool decks a vibrant blue and filling the pool with silk flowers and stuffed animals.

2. Shirling Sanctuary features one of the region’s most beautiful old-growth forests. But it’s not open to the public. Shirling Sanctuary is named for Albert Shirling, a high school biology teacher, naturalist, and writer who penned a book called Birds of Swope Park in 1920. His love for the wild parts of the park was so well-known that, in 1953, the Burroughs Nature Club (now the Burroughs Audubon Society) named the nearly ten-acre preserve after him. The specific place was chosen because Shirling thought it to be one of the park’s most beautiful. When the Kansas City Zoo’s Africa exhibit expanded in the 1990s, his sanctuary was absorbed into the Zoo’s holdings. Today, it remains behind Zoo fences for security reasons. Tour groups are periodically granted permission to access the Sanctuary. If you’d like to visit, keep an eye out for cleanup days sponsored by KC Wildlands.

3. Swope Park’s history has long been yoked to golf. When the park was originally established at the turn of the 20th Century, players would line up to hit balls at a series of holes near the park’s Grand Entrance. This ultimately became a problem for streetcar riders headed for the zoo; play had to be regularly halted so pedestrians wouldn’t get beaned with golf balls. Shelter Number 1 was once a concession stand and gold clubhouse, and 20 original wooden lockers can still be found in its basement today. And in the 1930s, the Swope Memorial Golf Course was designed by legendary golf architect A.W. Tillinghast (a big deal among golfing types). Though some changes were made over the years, the course was restored to Tillinghast’s original design in 1989.

4. Thomas Swope’s sensational death often overshadows the history of the park, though for understandable reasons. Swope built his fortune in real estate in the Kansas City area dating back to before the Civil War, when he began buying up tracts of land that he’d would later sell or lease at great profit. When he was in his seventies, Swope moved in with family in a mansion in Independence. Suddenly, one of Swope’s nieces died of a hemorrhage. Then did Swope himself died in 1908, and several other family members later contracted typhoid, which led to one of their deaths. Eventually, nurses became suspicious, and Bennett Clark Hyde, a doctor treating the family who had married one of Swope’s nieces, became the prime suspect in their deaths. He was convicted of murder in 1910, though the verdict was later overturned, and Hyde moved to Lafayette County, where he practiced medicine until he died two decades later.