Days after his death, reverent tributes continue to pour in for former president George HW Bush, celebrating his adroit handling of the end of the cold war and his victorious leadership in the 1991 Gulf war, all leavened with nostalgia for a bygone era in which an American leader could stand astride the world stage without causing the entire planet to titter in nervous laughter.

Refined, gracious and genteel, Bush, in many ways, was the polar opposite of the current resident of the White House. Nevertheless, his decorous manner often concealed objectives that were far darker than the “kinder, gentler” vision he promoted.

As head of the CIA under Gerald Ford, and later as vice-president, Bush was a consummate pragmatist capable of rapidly changing political positions as expediency demanded. Highly disciplined, he mastered the arts of compartmentalization and secrecy. Nobody in government was better at keeping secrets. With his posh pedigree and Ivy League credentials, Bush had the perfect résumé to be a spy, and an effective mask with which to disguise his real agendas.

As Murray Waas and I wrote in the New Yorker, that was precisely the case in the summer of 1986, when Bush received a call from William J Casey, the gruff, perpetually disheveled spymaster who succeeded Bush as CIA director. Casey wanted Bush, then vice-president under Ronald Reagan, to run a covert operation that was part of what became known as the Iran-Contra and Iraqgate scandals.

Obstinate Iranian leaders had declined Casey’s secret offer to exchange arms for hostages who were being held in Beirut by terrorists tied to Tehran. Casey decided he had to force Iran’s hand. In August, Vice-President Bush was scheduled to visit the Middle East to “advance the peace process”, as the New York Times reported.

Bush’s true objectives were exactly the opposite of his stated goals. He was there to escalate the war between Iran and Iraq. Specifically, he had been tasked with delivering strategic military intelligence to Saddam Hussein, so that Iraq would intensify its bombing inside Iran. After a series of brutal air attacks, Bush and Casey reasoned, Iran would be forced to turn to the US for missiles and other weapons of air defense.

And they were right. Forty-eight hours after Bush executed his mission, Iraqis launched hundreds of strikes targeting oil facilities deep into Iran. Within a few weeks, Iran was back at the negotiating table. But that wasn’t the end of it. Every time hostages were released, new ones were seized.

As for the Iraqi side of ledger, Bush and Casey were far less wary of Saddam than one might expect. “He and Casey both had great naiveté, thinking you could be friends with Saddam Hussein,” said Howard Teicher, who served on Reagan’s National Security Council.

When Bush became president in 1989, his administration blithely ignored Saddam’s military buildup and human rights violations and proceeded to send funding, intelligence and hi-tech exports, some of which could potentially be used in Iraq’s nuclear weapons program. All of which left Saddam emboldened – and that paved the way for the Gulf war of 1991.

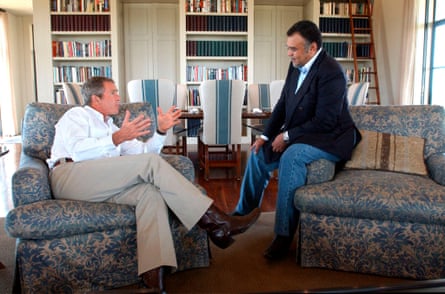

A key factor in Bush’s Middle East policies was his friendship with Prince Bandar, the Saudi ambassador to the US. The two men were so close that Bandar was known to pop in unexpectedly at Bush’s summer retreat in Kennebunkport, Maine. They went on hunting trips together. Later, when Bush was out of the White House, he even tasked Bandar with teaching his eldest son – George W, then a presidential aspirant with no experience in international affairs – all about foreign policy.

After his presidency was over, Bush and a number of his former cabinet officers also began participating in the Carlyle Group, a giant private equity firm heavily funded by Saudi billionaires – including the Saudi family of Osama bin Laden. As I reported in House of Bush, House of Saud, in the end, nearly $1.5bn made its way from the Saudis to individuals and institutions tied to the extended family of Bush cabinet officials and associates.

Such ties were particularly noteworthy because of the House of Saud’s alliance with strident and puritanical Wahhabi fundamentalists, many of whom supported a violent jihad against the west. All of which raised disturbing questions after terrorists murdered nearly 3,000 people on 11 September 2001 in attacks orchestrated by Bin Laden.

George HW Bush was long out of office and his son had become president. In the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks, when US air traffic was all but shut down, how is it that the White House approved the departure of more than 140 mostly Saudi passengers, many of whom were kin to Osama bin Laden? Why did Saudi Arabia – birthplace of 15 out of 19 hijackers – get preferential treatment from George W Bush’s White House at a time when Arab-Americans all over the country were being apprehended and interrogated? Had the Bushes’ close ties to the Saudis led them to look the other way – even after the worst terrorist attack in American history?

Seventeen years later, of course, a very different White House has turned a blind eye to a very different but equally horrifying Saudi atrocity – namely, the murder and dismemberment of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi after he was lured to the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

In response, Trump, predictably, could not have more deeply insulted the intelligence services Bush once led. Just a few days after the CIA determined that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman had approved the murder, Trump baldly defied CIA analysts and sided with the Saudis, asserting that Khashoggi’s murder might never be solved.

“We may never know all of the facts surrounding the murder of Mr Jamal Khashoggi,” he said. “In any case, our relationship is with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.”

With his understated style and his understanding of the diplomatic niceties, George HW Bush, of course, would have handled it very differently. But let us not forget that America’s mercenary relationships with brutal foreign powers began long before Donald Trump.

Craig Unger is the author of House of Bush, House of Saud and House of Trump, House of Putin: The Untold Story of Donald Trump and the Russian Mafia. His Twitter handle is @craigunger