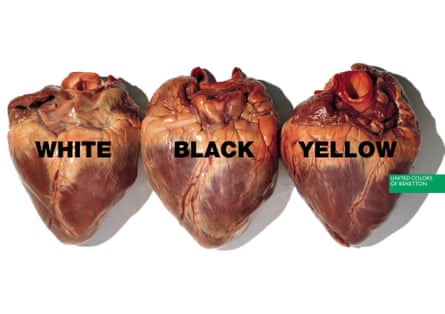

A newborn baby, still with umbilical cord. A nun and priest kissing. A white woman, black woman and Asian baby wrapped up together in a blanket. A man with Aids, on his deathbed, surrounded by his family. Three raw hearts, with the words “white”, “black” and “yellow” written on each. All of these images were masterminded by Oliviero Toscani as advertising campaigns for Benetton, where he was art director from 1982 to 2000.

He might be inclusive, challenging, fearless, exploitative or prone to over-simplification, depending on your point of view, but Toscani is definitely a professional provocateur. Throughout his 18-year tenure, he made Benetton ads talking points, never shying away from divisive visual statements that dealt with issues of the day including racism, religion and human rights. While a fashion advertising billboard was a contentious place for these images, Toscani’s reign was incredibly successful for the company.

Still, there’s always a line. Toscani was criticised for using a colourised Therese Fare image of David Kirby on his deathbed for a Benetton ad in 1990, but kept his job. The line was crossed, however, when Toscani put death-row prisoners in a campaign. The Observer called it “shock tactics that finally backfired”.

This week, Toscani is getting a second chance as he takes up the role at Benetton again. His first campaign since rejoining is an image of 28 schoolchildren in an Italian primary school, all from different ethnicities, all wearing Benetton, reading Pinocchio with their teacher. It’s a sweet image and, like a lot of Toscani’s, its meaning is pretty say-what-you-see. In an increasingly divided society, here’s his comment on multiculturalism and immigration. “There were 28 schoolchildren from 13 different countries, and four different continents,” says Toscani. “They studied together, they were educated together and they will shape future society.” He says that his past work was also about engaging with issues, not shock tactics: “When we talked about Aids, it wasn’t controversial, it was the reality.”

With fashion’s current awoke-ening, it makes sense that Benetton would tap up Toscani, a pioneer ahead of his time in bringing politics into the industry. The brand has lost its way somewhat, with various rebrands to try to lift financial results that include a net loss of €46m (£38.5m). Toscani’s straight-to-the-point images might lack subtlety but, in the age of real talk, they put Benetton into the debate. That said, his work for the brand so far has certainly been gentler than the imagery with which he made his name. It’s no surprise that he is treading carefully; you wonder how pictures as shocking as those he produced in the 1990s would go down in the social media era, when everyone with a smart phone has the ability to express outrage.

Toscani is still political in his work, however, and still keen to talk about the issues of the day – Brexit in particular. “The only contribution to Europe that Britain has made is the language,” he half-jokes. “You got pizza and wine and foie gras and Pinocchio.” He says the UK was where the image of the newborn baby was the most controversial. “If it had been a puppy, it would have been ‘Awwwww, a puppy!’” he says.

Toscani was born in 1942 in Milan, “when it [Italy] was fascist and the British were bombing the country. I was lucky they didn’t get me.” His father was a photographer – he has previously described Toscani senior as “the Italian Weegee” – and Toscani started taking pictures as a teenager. “I tell a story with images relating to the moment of history I am in,” he says, of his style. “I am a witness to my time or also my wishes of things that could be made better.” Those schoolchildren are part of his latest wish, and a bright hope for the future – for Benetton at least. “There used to be colour and magic,” he says, “and we are going to put the magic back.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion