The Austrian painter Maria Lassnig spent most of the second half of the 20th century being overlooked. Dealers and curators couldn’t see how to fit her work, which consisted entirely of self-portraits, into any of the usual groupings. She was at different times both figurative and linear, realist and allusive, full and spare. The only thing that stayed the same was her subject matter, which was always herself. Over a 70-year career Lassnig morphed her everywoman’s body, with its high colour, stocky limbs and snub nose, into a series of outlandish disguises. She was by turns baby, cheese grater, dumpling, robot, monster, lemon and elderly naked gunslinger.

This summer’s show of Lassnig’s work at Tate Liverpool, then, is both timely and in a sense already too late. For when Lassnig died two years ago at the age of 94, she was still a star in the making. Only in the last 15 years had her work begun to sell well; young artists were citing her as an influence, and in 2013 she was awarded the Golden Lion lifetime achievement award at the Venice Biennale. She had, though, lived long enough to be hailed as “the perfect artist for the age of the selfie”, although it’s an accolade that, at least initially, hardly seems to make sense. For Lassnig’s concern was never with serving up endless iterations of her body’s surface for the Instagram generation. Deep internal processes were her beat. Developing what she called “body awareness painting” – “Körperbewusstseinsmalerei” – Lassnig depicted pain, thought, blood and breath, as if they were objects she could hold and scrutinise. “The truth,” she once explained, “resides in the emotions produced within the physical shell.”

Despite what this sounds like, Lassnig was not given to self-indulgence. She restricted herself to depicting only those parts of herself that she could physically feel: if the back of her head went numb she left it out, if her ears seemed unreachable they went missing, and she rarely painted her hair on the grounds that it was already dead. The result was a body on the canvas that often looks partial, even deformed. In a Lassnig painting limbs are regularly abbreviated into vestigial knobs, a torso is detached, an ear ends up on a dinner plate. The stark white backgrounds, meanwhile, refuse to provide any clues as to how to read these absences and displacements. It would be hard to imagine an art less concerned with the banality of how things look.

It is, nonetheless, an art that is deeply pleasurable to view. Whether she was in representational or abstract mode, Lassnig’s use of colour is always sublime. In the otherwise abrasive You or Me (2005), in which she is posed naked at 85, wielding two guns, she plies luscious flesh tones of salmon pink, outlined in acid yellow and teal. In the much earlier Body Housing (1951) she renders her body as a pistachio-coloured cave with pinky black interior. On other occasions colour manages to bleed into the title. Fat Green (1961) is an abstract made up of thick gestural lines of blue-green and yellow-green with accents of red that, after inspection, resolve themselves into the back view of a body. Figure with Blue Throat (1961), meanwhile, uses a deep Marian blue that could have come straight out of the Austrian baroque.

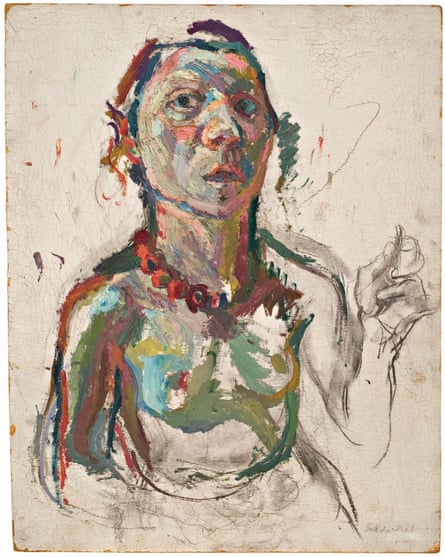

Historical precedent had always been a valuable resource to Lassnig, especially during her early years under Nazi rule. Enrolling at Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts in 1940, she soon found herself locking horns with a politically cowed faculty that, she later claimed, permitted her to paint nothing but peasants in the approved social realist style. By way of resistance the young Lassnig reached back into the canon of Austrian expressionism, particularly the work of Egon Schiele and the still-living Oskar Kokoschka. You can see their influence in the first piece she produced as a professional artist. The pointedly titled Expressive Self-Portrait of 1945 is a fretful, brushy inquiry into what it feels like to inhabit a human body at a moment in history when humanity itself appears to be broken. What’s more, in this early work Lassnig’s interest in the formal problems of self-representation is already in play: her paintbrush, primed to make its mark, is in her left hand whereas in real life she was actually right handed. This is already a looking-glass world.

As Austria began to open up after the war, Lassnig was increasingly exposed to foreign influences including cubism, as well as a more up‑to-date abstract style known as art informel. In 1951 she went to Paris on a scholarship, where she became friends with surrealists including André Breton and the poet Benjamin Péret. It is, though, the influence of René Magritte that is most obviously enduring in such work as her ambiguously titled Drawn By Death (2011). This is a piece from near the end of Lassnig’s life in which Death, rendered as an odd assemblage of mechanical prostheses but with a supple, dexterous hand, is painting a comatose Lassnig into being. In its grim playfulness the painting follows Magritte’s lead in revealing the limits of art’s ability to give a full account of the three dimensional human body.

Throughout her life Lassnig had a knack of moving away from where her best interests seemed to lie. In 1968, just as Paris was fizzing with the kind of radical energies that you might assume were conducive to her art, she shipped out to New York. In a city where a kind of flattened subjectivity now reigned supreme, with artists including Andy Warhol insisting that it was the viewer rather than the artist who made meaning, Lassnig found her brand of painterly figuration resoundingly out of favour. Galleries returned her portfolio with the message that her work was “strange”, “morbid” or even “sick”. The final straw came when a neighbour told Lassnig “You just can’t paint”.

What the powerbrokers and the punters alike missed was that Lassnig’s work, while self-absorbed, represented much more than the ramblings of a crazy lady. This was not naive, still less outsider, art. Lassnig’s starting point may have been her gut feeling, but what she did with that feeling was always artistically knowing and intellectually nimble. In a series from the 1980s, Inside and Outside the Canvas, her painted figures struggle to climb into the painting or to wriggle out of it. One has got completely stuck, and wears the canvas like a dress while another figure sprawls on top, as if trying to muscle its way in. Far from being whimsical or cute, Lassnig provides a succinct and witty account of the difficulty of translating bodily sensation into a visual language.

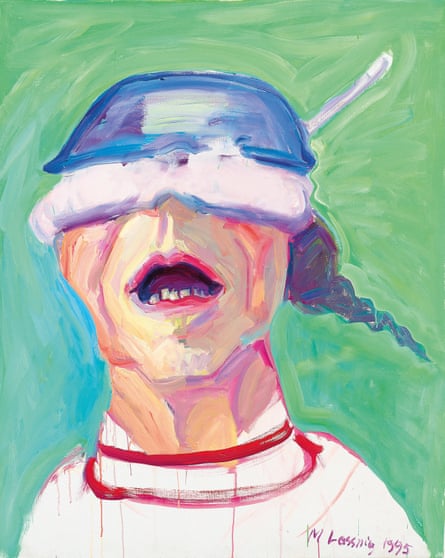

The wider political context was important to Lassnig too, and brings air into what might otherwise feel like suffocatingly personal art. A series of Kitchen War paintings from the 70s critiques women’s relationship with domesticity, something with which Lassnig herself struggled (“a man, a child is not my destiny”). In The Kitchen Bride (1988), the artist transforms herself into a giant cheese grater and makes a bow of obeisance to the household gods. Meanwhile in Self-portrait with Saucepan (1995), she wears a cooking pot on her head. At first glance the utensil seems to function as a protective helmet, until one realises that it is jammed so low over her eyes that it blinds her completely. In protest Lassnig’s mouth hangs open in a characteristic gasp of bewildered rage.

Lassnig’s interest in feminism could perhaps have been anticipated – she had relocated to New York because, she maintained, it was the country of “strong women”. More unexpected is the fact that she went on to tackle the relationship of the human form with emerging technology. In Small Science Fiction Self-Portrait (1995) she shows the upper part of her face covered with what appears to be a virtual visor, a precursor of Google Glass. Meanwhile in Language Mesh (1999) she has replaced her vocal cords with a thickly painted grid, a reference perhaps to the fact that language is a matrix that both enables and limits communication. The rest of Lassnig’s face remains densely scaffolded and only partially complete, a reminder of the human form’s always precarious and provisional status.

But it was with regards to her own artistic practice that Lassnig’s interrogation of technology became most loaded. Photography Against Painting (2006) shows a cowering pile of flesh holding up a jeering Lassnig face mask to taunt a leggy eyeball-turned-camera. Far from it offering an aid to depicting life as it really was, Lassnig believed that photography’s inability to delve below the surface of things meant that it offered nothing more than a persuasive lie: “I need the real body, real air,” she once explained, “When I paint I want everything to be as direct as possible.” For that reason she could never understand why Francis Bacon used photographs rather than real models to produce his compositions of twisted, mangled flesh. (One of the ironies here is that Lassnig will be sharing space with Bacon, whose work can be seen on adjacent walls at Tate Liverpool this summer. The other irony is that while Lassnig was acutely aware of Bacon as a “genius”, the reverse was almost certainly not the case.)

And yet, while still photography struck Lassnig as a kind of crude deception, the moving image made her hopeful. In the 70s she turned to animation to tell stories about her body’s passage through the world. Best of these, and available to view at the show, is Kantate in which Lassnig tunelessly croons her autobiography to an Austrian folk jingle while dressed as anything from a punk rocker to the Statue of Liberty. Whatever you think of the result – clever or merely kitsch? – Kantate prompts the realisation that, even when she is confining herself to canvas and paint, Maria Lassnig is essentially a performance artist.

Indeed, it is this concern with the performative elements of her autographical painting that starts to bring sense to that earlier claim about Lassnig being the perfect artist for the selfie age. Again and again her paintings return us to the acute tension between how we feel ourselves to be – messy, inarticulate, barely there – and how we are increasingly obliged to present ourselves to the world – coherent, persuasive and whole. In acknowledging the gap between the two, and dramatising it in such a luscious way, Lassnig doesn’t merely provide a feast for the senses but also a balm for the fretful soul.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion