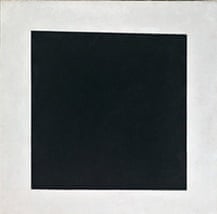

At the heart of Kazimir Malevich's art is a statement so final that everything else orbits it. Emphatic, plain and declarative, his Black Square has a modest, expressionless presence. It seems like a last word. But what was it? An abstract icon? A tombstone for pictorial art? The portrait of an idea? Or a thing in itself? Perhaps not even Malevich knew.

What do you say when you have said the last word? One solution is to keep on saying it. Existing in several versions – the first was painted in 1914 or 15, the last in 1929 – Malevich's Black Square is both beginning and end. There's depth in the black. It seems to be as much volume as surface. It is simple, it is complicated, and Malevich said that it had been painted in a sort of "ecstatic fury", though each version seems calm and emphatic. The painting looks back at you, blankly, saying nothing, giving nothing away.

Or almost nothing. The Black Square was hung across the spot where walls and ceiling meet, like a Russian religious icon. It took the place of a signature in Malevich's last, figurative paintings. A black square was wedged between the headlamps of the truck that carried his coffin on a grey May morning in Leningrad in 1935. It appears again in a little drawing, seen in perspective, being borne flat on a stretcher like someone wounded. As well as black squares, there were black quadrilaterals and crosses, white-on-white squares, and an off-square red shape titled Red Square (Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions). Red squares met black rhomboids, circles and wedges.

Malevich's art advances and retreats throughout his turbulent career, and now fills a suite of galleries at Tate Modern, complementing the exhibition of Matisse cut-outs that continues until September. Born in Kiev to Polish parents in 1879, Malevich lived through artistic and political revolution. He was embroiled in both. The opening rooms of this extensive retrospective show a bewildering set of influences: Russian folk art and dutiful 19th-century portraiture, Gauguin and Van Gogh, Monet and Cézanne, Matisse and Picasso. All of whose work Malevich had seen as early as 1905, when he encountered two of the greatest collections of western avant-garde art in Russia, or indeed anywhere, belonging to Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov.

Symbolism and impressionism, cubism and futurism – all found their way into Malevich's painting. But he was never playing catch-up, and he managed early on to effect a synthesis of these influences.

Here is a church, seen through bare trees, the whole painting in bleached snow-light and thin yellow sun, the paint heavily flecked and crusted (I imagine the crunchy sound of boots on frozen snow); then a Gauguinesque self-portrait, the artist full-faced with an almost glowering concentration. And here, men in smocked shirts doing a lumbering dance as they polish a floor with lumps of pumice under their bare feet.

Malevich's echoes of Matisse, Picasso and the rest were combined with imagery depicting the lives of the Russian peasantry. His variants on cubism contained touches of realism: a collaged image of the Mona Lisa, and the head of a highly representational bearded middle-class man. They became filled with nonsense words; there was a meeting between a cow, a violin, a fish and a wooden spoon (like the spoon that poked out of his jacket pocket as though to announce his outre modernity).

In 1913, Malevich collaborated with musician Mikhail Matyushin and poet Aleksei Kruchenykh on the production in St Petersburg of an opera, Victory Over the Sun, a mad (and maddening) futurist-inspired show, restaged at UCLA in 1984 and screened alongside a number of austere geometric suprematist paintings. With its discordant music and nonsensical libretto (based on Kruchenykh's idea for a language "beyond reason" called zaum), the opera was created at a time when Malevich was developing what he called "alogical painting", wanting to wrest painting away from its duty to render a world of myths, stories and representations.

This is where the real thrust of the exhibition, and Malevich's art, lies. One room attempts a partial reconstruction of a 1915 exhibition, The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10, in which Malevich's suprematist paintings hang on a tight array around the walls, a Black Square being their nodal point. The room is full of life and energy, jostling and stillness.

Coinciding with the build-up to the Russian revolution, Malevich foresaw not a new beginning but an end of painting. Forms began to dissolve or fray along one of their edges, or grow anaemic or muffled, as if in retreat. They are sometimes like sentences tailing off. For all that, they look peculiarly modern, current, almost as if they belong not in pre-revolutionary Russia but in the present – which, in a sense, they do.

In 1919, Malevich travelled to Vitebsk, in what is now Belarus, to take up a teaching post in a school founded the previous year by Marc Chagall. Chagall, it seems, was soon sidelined and left. Hung with utilitarian lamps, and with the lower section of the walls painted a grim institutional grey, the room devoted to this could almost be part of one of Ilya Kabakov's sardonic installations, but for the many vitrines that crowd the floor, and the teaching charts, drawings and paintings that fill the walls. Standing here, one has the feeling that one is in the midst of a maelstrom of thinking, theorising and play.

Following this is a large gallery that covers the entirety of Malevich's career in drawing. This too could be an exhibition all its own. Having abandoned painting, Malevich returned to it in the late 20s. Often his later work is regarded as a kind of unwilling subservience to the changing situation in Russia; he had applied for political asylum in Poland and was rejected. Figures and rural scenes predominate, although the figures themselves have a wonderful, almost stoic plainness. Even at their most abstracted, these figures have a dignified air. They stand in rows and alone in fields and hinterlands. They're terrific. The faces are often blank.

But in the last three years of Malevich's life – suffering from cancer and following a period of imprisonment and interrogation, having been accused of spying for Germany – his paintings become more troubling. The strangest combine a kind of dutiful realism with costumes that look as if the renaissance has been run through a suprematist mill. The portraits exude a dead calm. There are some turgid portraits of men with beards, and one of the artist's wife, wearing a little abstract suprematist brooch. This last room is a kind of theatre, everyone dressed up, nowhere to go, the future unknown. Only the black square, used to sign these paintings, tells us what Malevich felt.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion