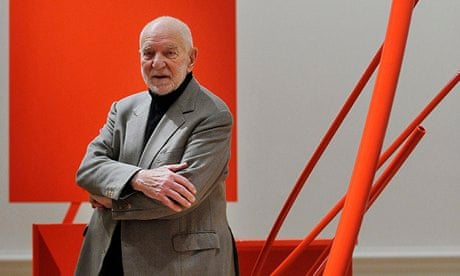

The career of Anthony Caro, who has died aged 89, was so enduring and substantial that it long seemed part of our permanent British art landscape. We are good at that – ignoring our best artists until we can take them for granted. There was a short period, at the start of the 1960s, when his new work drew a lot of attention, at a time when British art was erupting with new energies and optimism: St Ives going strong, plus situation painting, pop art, op art. By the mid-60s he was firmly established. His work was being shown, discussed and beginning to be bought on both sides of the Atlantic.

He had had an exhibition of new work at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1963, and he was teaching at St Martin's School of Art. Thus, in 1965, New Generation at the Whitechapel featured sculpture done mostly by people who had studied under him or were teaching with him. He was now chef d'école to a degree that no sculptor had ever been in Britain – and no sculptor anywhere since Rodin. On the other hand, though he did cause a lot of young sculptors to make abstract sculpture in welded steel, his example led others to find their own methods and idioms, even to reject formal sculpture altogether – for example, the young Barry Flanagan, Bruce McLean and the Gilbert and George partnership.

By rights, Caro should have been made president of the Royal Academy. Abstract art still riles Britain's cultural upper crust, but major abstract artists have been academicians for some years. Caro could well have stood at their head; some of his best artist friends are among them. But he stayed out until 2004, the year the presidency of his former pupil Phillip King ended. There was always a private side to the man, for all the calls of international fame. The work came out of intimate thought and doing, not out of polemics. One feels it was centred on his family life as much as in the potency that made him decide to be a sculptor, not an engineer.

He was born in New Malden, south-west London, the youngest of the three children of Alfred Caro, a stockbroker who had married his distant cousin Mary Rose. At Charterhouse school, Surrey, his interest in sculpture was encouraged by a housemaster who introduced him to the sculptor Charles Wheeler, later president of the RA. Young Caro worked with him in the holidays, learning the traditional methods of sculpture. He studied engineering at Christ's College, Cambridge, from 1942 to 1944 and got his degree, but still worked on sculpture in the vacations, at Farnham Art School, Surrey, followed by two years in the Fleet Air Arm.

By 1946 the die was cast. He went full time to the then Regent Street Polytechnic (now part of the University of Westminster) and the Royal Academy schools, becoming well grounded in traditional techniques and materials and in the aesthetics of ancient and medieval sculpture. Medals and other awards came his way in 1948 and 1949. That year he married a fellow student, the painter Sheila Girling, with whom he had two sons, Timothy, born in 1951, and Paul, born in 1958.

Their mutual professional criticism was important to both their careers. The best room at the 2009 summer show of the Royal Academy had Erl King, a grand metal sculpture by Caro, opposite a glowing abstract painting by Girling. Two years earlier, at Roche Court sculpture park, near Salisbury, Wiltshire, the couple had shown together for the first time in their marriage: he with a dozen huge, rusted steel pieces from the series called Flats, made in 1974 in Canada with the aid of a crane; she indoors with a sequence of vibrantly coloured canvases painted with architectural forms not far distant from his.

In late 1959 Caro visited the US, talked with the critic Clement Greenberg and became friends with painters such as Kenneth Noland and Helen Frankenthaler. He also saw constructed sculpture by David Smith, whom he got to know well in 1963.

Back in London, in 1960, he bought welding equipment and scrap metal and completed his first abstract sculpture. It seemed he had undergone a Pauline conversion. His previous work had been modelled, like most of Henry Moore's, for whom he worked part-time from 1951 to 1953. In the later 1950s he had incorporated stones in his clay figures before casting them in bronze, unlovely but powerful forms that seemed expressionist but had more to do with bodily sensations of weight and energy than with emotions. These figures attracted attention and in 1959 he won top prize for sculpture at the first Paris Biennale des Jeunes. The American experience seemed to have swept him off his feet.

But the new work was powerful too, and as disconcerting at first sight as the massive figures. The now welded, sometimes bolted, steel sculptures were without bases or figurative references. The first had something rustic about it, plain forms fixed together and painted in dark colours with industrial paints. By 1962 he was using aluminium as well as steel, adding bright colours and titles such as Hopscotch and Early One Morning. The sculptures had expanded to 20ft and occupied the air as much as the ground. Sculpture had not sung like that since Brancusi launched his soaring Birds in the 1920s.

In the mid-60s Caro was regularly in the US, teaching and working at Bennington College, Vermont, alongside such painters as Jules Olitski, and he continued to maintain close contact with the US, so much so that American reference books claim him as a native. In 1964 Greenberg wrote of him: "Without maintaining necessarily that he is a better artist than Turner, I would venture to say that Caro comes closer to the genuine grand manner – genuine because original and unsynthetic – than any English artist before him."

Caro had a one-man show of figure sculptures at Gimpel Fils in London in 1957, and his second was the Whitechapel show in 1963. The following year he showed in New York at the André Emmerich Gallery, and from 1965 on he featured regularly at Kasmin in London and at Emmerich's. Later his London galleries were Waddington and then Annely Juda Fine Art.

What he had found was not a new category or process but a whole new field for exploration. No one had known it was there. He explored it with an avidity and sureness of instinct that stayed with him to the end and marked him a genius. But exploration can demand changes of direction, and these worried even his admirers. I recall regretting his very severe linear sculptures in 1965, which I now admire, and in 1967 praising the more engaging Prairie with an enthusiasm I still feel. All his new pieces, until the late 60s, sat on the floor, in real space, and had to earn their right to be there by involving us in their doings or impressing us by their presence. Unusually, Caro seemed to steer by basic principles, then quickly abandoned these to demonstrate others just as basic.

His 60s sculptures were conditioned by the extended horizontal plane, though almost at once they started lifting off the floor and denying gravity of matter and spirit. In the mid-60s he reined them in as though in penance for his ebullience, but then this concentration on a few elements led him to use steel mesh, to magical effect, and thus on to the floating horizontals of the sand-coloured Prairie.

By the end of the 60s, he was setting ploughshares into space like petals. But in the late 60s he also started making his "tabletop pieces", smaller sculptures that sit on or hang over the edge of a table or box. These were never maquettes for bigger works. They were chamber music, and often quite sprightly too. He used assistants on his large pieces – to try different compositions often involving large pieces of steel, weld or bolt them and then treat their surfaces in various ways. The smaller pieces could be more private, intimate in a way sculpture rarely is. Their composition, the elements of which they are formed and their overall result, is always surprising.

It is as though, as well as being the Jackson Pollock, the Willem de Kooning, the Clyfford Still, the John Hoyland and the Robyn Denny of sculpture, he was also the Paul Klee. Working with scrap metal meant working out of a response to material and forms and to compositions as they developed. This genetic process is constructed sculpture's special gift to art, but though Picasso had opened that door, nobody until Caro had opened up the vast territory beyond it. Caro worked with steel and welding the way the best modern painters have worked with paint and canvas, with colour, form and surface so interactive that the artist's role becomes inseparable from theirs. Other constructing sculptors have made sure their work had its brand image, but Caro went on finding new things to do, new tunes to play.

Music was important to him, mostly classical, while jazz and pop were no enemy. He enjoyed the arts at large: Donatello, Matisse, ancient, modern, Indian, African. He was well read. But culture and learning are never paraded in his work. The nearest he got to that was with the Trojan War sculptures he showed at Kenwood House, Hampstead, in 1994; welded steel combined with fired ceramic to make vertical forms suggesting figures. Is nothing sacred? Literary associations in abstract art? Ceramic with steel? He had started using that combination in the 70s, as well as using cast bronze with steel and lead with wood and with glass fibres in resin, and even just bronze and just paper. Figures? Artists do not draw lines between abstraction and figuration.

Caro's work had become emphatically vertical with the Veduggio series of 1972-73, using large, soft-edged, pastry-like steel offcuts he found in Italy, and also emphatically natural and earthy because he varnished them to keep the rust rather than clothing them in paint. He enjoyed the soft forms of the steel in these lovely new pieces, warm as well as grand, but hardly had he begun showing them than he started working in stainless steel, and then in silver for his 25th wedding anniversary.

In the mid-80s he made bronze variations on an Indian carved relief of female warriors, and a visit to Greece in 1985 was reflected in a series of sculptures as variations on the pediments he admired there. In 1990 he welded his version of a Rembrandt Deposition from the Cross, which now stands in the ante-chapel at his former Cambridge college. In 1984 he started making "sculpitecture" – small and full-size models of pavilions. "Architects do not get their hands dirty enough," he said at the time, with Richard Rogers welcoming this "architecture free from necessity" in 1989.

Both in his heavily physical figures and in the almost infinite variety of his sculptures, Caro made sculpture free from any necessity but that of holding and moving our spirits. He produced energetically, was in countless mixed shows around the globe and about 130 one-man shows, including one at the Serpentine Gallery in 1984, subsequently seen abroad, along with that show of a few very large pieces in the Duveen gallery of the Tate in 1991. The most resplendent was that in Rome in 1992 – 39 pieces dating from 1960 to 1987, superbly displayed in the ancient Trajan's Markets in Rome. In 1995 his was the second show, and the first solo show, to be presented in Tokyo's new Museum of Contemporary Art.

Over several years after the turn of the century, Caro worked on a project in the newly restored choir of the church of St Jean-Baptiste in Bourbourg, in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais, which had been wrecked when a second world war RAF pilot crashed on to the roof to avoid hitting houses. Caro linked the nave and choir with sculpture in the Corten steel that had become his favourite material, and in the choir built wooden towers, a spiralling concrete font and sculptures of steel, terracotta and wood in the niches of the blind arcade running around the choir and rounded apse. It is a monumental work, reflecting the twisted metal and broken stone of the wreckage but evoking the creation, a work to rival the ambition of Matisse's Chapel of the Rosary at Vence. The new chapel was reconsecrated in 2008.

In 2012 Caro displayed sculpture made over 40 years at Chatsworth park around Canal Pond and the Emperor Fountain. It was clearly not a concession to the English pastoral tradition into which Moore had fitted so easily, but an architectural statement as pronounced as Chatsworth House itself.

Moore had been the most famous sculptor after Rodin. Caro was the most famous after Moore. They were in some ways opposites. Whereas Caro might have been a great Moore disciple, he chose to be something more like a son, rejecting much of what the old man had stood for but matching his professionalism and vigour. He had many British and American honorary doctorates and fellowships, was knighted in 1987, and in 2000 he became the first artist since Moore to be awarded the OM.

Caro was close to many people and enjoyed long friendships, but he was not a great socialiser. One thinks of his friendly glance and ready smile, and of his pipe. If one met him in a gallery, Sheila was usually with him. In his studio he had trusted, long-term assistants. He spoke well about his work, and taught occasionally long after he stopped needing the money. Though one still felt he was a private person, and never one to preen himself, one could see him enjoy an audience.

He was a good man as well as a great artist (the two do not always go together). He has left no great theories but a lot of fine, sometimes magnificent sculptures, and a sense of creative joy that will stay with them.

Sheila and their sons survive him.

Anthony Alfred Caro, sculptor, born 8 March 1924; died 23 October 2013

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion