In November 2011, Roy Lichtenstein's 1961 I Can See the Whole Room … and There's Nobody in It! was sold by Christie's for $43.2 million. The painting depicts a large back square, out of which a circle has been cut. From behind the circle peers the face of a jutting-jawed comic-strip man, illuminated by a bright background of yellow. He is looking through a peephole, at the viewer; above him a dialogue bubble declares that he can see no one in the room where we, presumably, are standing. The irony shoots in many directions, not least towards that perennial question demanded of modern art: is there any there there?

Painted in the same year as his breakthrough Look Mickey, the work in which Lichtenstein first discovered the possibilities of using cartoons and comic strips, I Can See the Whole Room … and There's Nobody in It! encapsulates Lichtenstein's wittiness and insight. The painting quotes abstract expressionism – the image suggests such seminal works as Kazimir Malevich's 1915 Black Square – while entirely subverting its tone. The avant garde confronts kitsch, the old world confronts the new, the individual confronts the mass-produced, and the confrontational confronts the jocular, even as the visible is declaring its viewers invisible. But Lichtenstein is just as willing to efface the image, and its maker, as his audience: in his 1978 Self-Portrait, he puts a blank mirror where the artist's head should be.

At the same moment that Lichtenstein was discovering that he could use popular culture to ask searching questions about concept, form and technique, Andy Warhol was, quite independently, also using cartoon in his experimental work: neither artist knew it yet, but Pop Art was about to spring fully formed from America's forehead. The nation did not initially enjoy looking in the mirror that Lichtenstein and Warhol were thrusting toward it: in 1964, Life magazine asked of Lichtenstein, "Is he the worst artist in America?"

Half a century later, the first major exhibition since Lichtenstein's death in 1997 has arrived at Tate Modern, having travelled from the Art Institute of Chicago, where it opened last year. Although it took a while for museums to warm to Lichtenstein's then heretical blending of high and low art, the original and the copy, the serious and the trivial, satire and homage, mechanical and handmade, produced and reproduced, far-seeing connoisseurs recognised something new and exciting, and immediately began collecting him.

His work explores ideas of clichés and icons, the ersatz and the manufactured. In the beginning, cartoons and comic strips provided his source material, although he soon moved away from them. But he never abandoned his signature method, the Ben-Day dot (named after inventor Benjamin Day's 1879 technique for reproducing printed images by using dots to recreate gradations of shading), ensuring that his work would remain as recognisable as it was quotable.

Lichtenstein's paintings are far more technically demanding than it seems at first glance. His work was described by the critic Hal Foster as the "handmade readymade": not industrially mechanised, but blending careful techniques of handwork (drawing, tracing, painting, emphasising brushstroke, line, and Ben-Day dot) with the reproduction and screening of found images. It is not art trouvé but art retrouvé: refashioned, recovered, reframed. And in the process, our simplistic distinctions between making and manufacturing begin to dissolve.

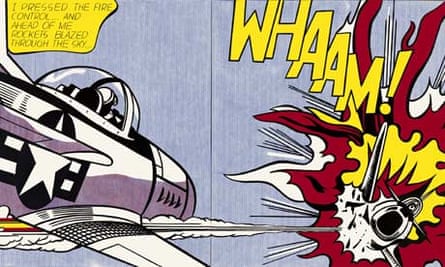

Like Marcel Duchamp before him, Lichtenstein was criticised for not producing original art but plagiarising the originals. Unlike Duchamp, however, Lichtenstein couldn't even offer the avant-garde defence of aggressive "obscenity": his work is resolutely unconfrontational, tonally serene, even when the subject matter (such as Drowning Girl or WHAAM!) is pain or violence. This led to persistent accusations of detachment, distance, a frigidity that some say makes his work hard to love. Conversely, others charge that Lichtenstein's art is too lovable: too accessible, commercial, art "lite" for the merely acquisitive.

His work tests the contradictions at the heart of our ideas about art and taste: reproduction enables accessibility and democratisation (good), but prompts anxieties about vulgarisation and popularisation (bad). But vulgarisation, Lichtenstein said, was what he was exploring: "The colour range I use is perfect for the idea, which has always been about vulgarisation." The Ben-Day dots, too, were meant to suggest the manufactured and simulated: "The dots I use to make the image ersatz. And I think the dots also may mean data transmission." The work is "supposed to look like a fake, and it achieves that, I think," he explained.

It is no coincidence that Lichtenstein's painstaking, hand-made works about reproduction do not themselves reproduce well: when they are reproduced, they lose their individuality, specificity, scope and delicacy. But the ideas remain, and they are wiser and more prescient than is sometimes acknowledged. Along with the other pop artists, Lichtenstein helped to suggest that any representation is mediated, emphasising new ways of seeing in the age of the industrialised image.

What is the relationship between imagination and the images that have shaped it? As I Can See the Whole Room … and There's Nobody in It! suggests, Lichtenstein asks questions about perception and environment: apertures and camera shutters, peepholes and voyeurism, frame and screens define the way we view our surroundings. "My work isn't about form," he once said. "It's about seeing. I'm excited about seeing things, and I'm interested in the way I think other people saw things."

What he saw, and saw others seeing, was mid-century America in all its tawdry grandeur: a brash, jazzy, garish world of bright colours and arrested motion, industrialised and mechanised, through which real human experience keeps pushing its way. Lichtenstein brings noise and narrative into painting, introducing time and motion into a still life. The sensibility of much of his work is not far from the mid-century Hollywood musical: an unnatural, stylised world of primary colours, formulae and clichés, featuring carefully designed outbursts of spontaneous emotion, painstakingly recreated. Lichtenstein's meticulously hand-painted dots may be no more reminiscent of French pointillism than of Fred Astaire re-recording each tap in a tap dance for the film's soundtrack. And like the Hollywood musical, his work has been accused of nostalgia, conservatism, appeasement, even as it is celebrated for its energy, technical skill and charm.

Roy Fox Lichtenstein was born on 27 October 1923, and raised in New York City, the son of affluent middle-class parents. It was the jazz age; Scott Fitzgerald was in the midst of the parties that would inspire The Great Gatsby. The young Lichtenstein grew up surrounded by that world of exploding mass culture and commercial advertisement, jazz and prohibition (the peephole in I Can See the Whole Room has suggested the speakeasy to some viewers). Surrounded by the art moderne of the 1930s, influenced by the geometrical, modernist world of art deco and futurism, Lichtenstein also loved the superheroes of radio and film serials, and the popular music of his day, especially jazz. One of his finest paintings, The Melody Haunts My Reverie, features one of his perfect blondes (recently, and accurately, likened to Betty Draper in Mad Men) crooning a line from "Stardust" by the great Hoagy Carmichael.

He studied art at Ohio State University until the second world war interrupted his studies. Sent to Europe, he worked as a draughtsman, among other duties, and encountered European art, including exhibitions of Cézanne and Toulouse Lautrec in London. After the war, he returned to Ohio, where he completed his degree and taught art for the next 10 years, while he pursued his painting, searching for an original style. He returned to New York in 1957, and four years later had his breakthrough with Look Mickey.

When the dealer Leo Castelli took him on in 1961, Lichtenstein joined a group of artists that included Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, and whom Warhol would soon join and eclipse, at least in the celebrity stakes. For the next 45 years Lichtenstein remained at the forefront of the American art world. The conspicuous in America interested him, he said in 1965: "I think there's the apparent lack of subtlety and sort of make-believe anti-sensibility connected with American art. I think this is a style and it does relate to our culture and I think it would be anachronistic maybe to pretend to be involved with subtle changes and modulations and things like that because it's really not part of America."

But such a statement was not necessarily a criticism. "The things that I have apparently parodied I actually admire," Lichtenstein said, and humour is as central to his work as is a very American buoyancy. Even the 1963 Drowning Girl is defiant: "I don't care! I'd rather sink – than call Brad for help!" the girl's thought bubble declares. Lichtenstein added later that, as far as he was concerned, the drowning girl didn't drown. This relentlessly sanguine perspective, his cheerful willingness to celebrate rather than to excoriate, continues to mean that some will always view him as a lightweight, an artist manqué who sold out to the juggernaut of American popular culture. But context is crucial to parody and pastiche: pastiche reframes the work of art both literally and metaphorically, making us look at it anew. As with most modern art, parody and pastiche mean that the artist must also be a critic, engaging with a tradition that has been inherited without being overwhelmed or suffocated by it.

And cliché, Lichtenstein maintained from the start, was central to his work. He was fascinated by the possibilities of reanimating a dead metaphor, playing with the bromidic visual formulae of mass culture, asking questions about inarticulacy, probing the tension between surface and depth. For an artist so interested in reproduction, he also understood the dangers of repeating himself, and worked hard to keep reinventing his work by turning to new themes and source material.

Reimagining Monet's iconic series of Cathedrals and Haystacks, for example, Lichtenstein explained that they were "meant to be manufactured Monets", at the same time as they were "a play on cubist composition", borrowing imagery from the 1930s. "The theme is hackneyed, which is part of the idea": the Monets "deal with the impressionist cliché of not being able to read the image close up — it becomes clearer as you move away from it."

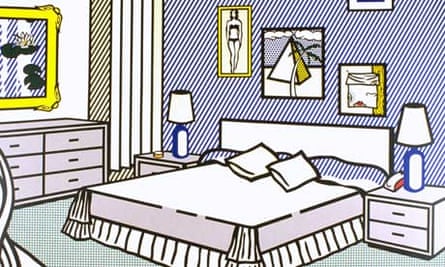

When he turned to Van Gogh's famous room at Arles, Lichtenstein's sense of humour itself became a way of exploring that painter's romanticised "madness". Lichtenstein painted Bedroom at Arles, not after The Artist's Room at Arles, but after a postcard of it, offering a tongue-in-cheek explication of how his painting "improved" Van Gogh's: "I've cleaned his room up a little bit for him; and he'll be very happy when he gets home from the hospital to see that I've straightened his shirts and bought some new furniture. Mine is a rather large painting and his is rather small … His is much better, but mine is much bigger." This might seem merely facetious, but it subverts our supposedly straightforward evaluative criteria, while affectionately poking fun at American values, reminding us that bigger is not always better.

Lichtenstein added in a more serious vein: "Where the Van Gogh is so emotional, and feverish, and spontaneous, my work is planned and premeditated, and painfully worked out." Lichtenstein is a conceptual artist who uses conventional representations to explore his abstract concepts. He liked using cartoon symbols, such as seeing stars, or the curving lines that indicate an arm in motion, because, he said, they "related to the way the futurists would have portrayed motion. There are certain marks, like these, that I am fond of using because they have no basis in reality, only in ideas." And yet they convey ideas about how to depict the most physical of our realities: motion, time, collision. When Lichtenstein is faulted for being emotionally reserved, this is to deny that humour has an emotional impact. It can be defensive, but it can also be a profound point of connection, connectedness, even of sorrow and regret, and certainly of self-deprecation in an art world often accused of overweening narcissism.

Look Mickey, in which Donald Duck exclaims that he's hooked a big one, features Donald raptly leaning toward his own image in the water, a Narcissus confronted not by his face, but by the artist's signature, a small, sardonic, "rfl." Or take the famous Masterpiece, which features another Hitchcock blonde admiringly telling the square-jawed artist: "WHY, BRAD DARLING, THIS PAINTING IS A MASTERPIECE! MY, SOON YOU'LL HAVE ALL OF NEW YORK CLAMORING FOR YOUR WORK!" He wasn't wrong, but he kept laughing at himself, and that in itself is a virtue worth preserving.

When Lichtenstein died of pneumonia at the age of 73, his last words were: "Well, here I go," a sentiment that could have appeared in one of his dialogue bubbles – humorous and forward-looking to the end.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion