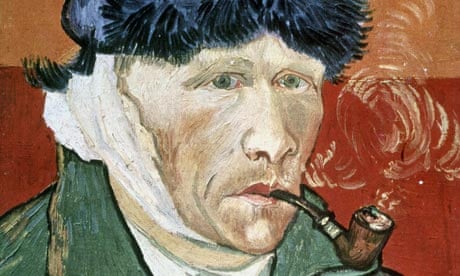

The tough Mediterranean grass jabs your eyes with emerald and sea-green, olive and fire. It is overpowering that anyone can see so much colour, life and mystery in a little patch of ground. When you know more about when and where the canvas that now hangs in London's National Gallery was glorified with colour, it is still more moving.

Vincent van Gogh painted Long Grass with Butterflies in 1890 in the grounds of an asylum, where he was a patient. Whenever he was well enough in the hospital at Saint-Rémy in Provence he set up his easel in its gardens or went under supervision into the surrounding wheatfields. But he was not always well enough. He came to the asylum after suffering hallucinations – and these hallucinations returned. During his bad periods he tried to stuff the paints into his mouth, washed down by turpentine – to poison himself with colour.

Look at this painting in the light of those facts. Picture the mental patient standing there, staring at the ground. Then look at what he sees. He sees grass as firm as flesh. He sees colours as full as the heart. Nature absorbs him. To look at this painting is to look at something heroic. Nothing is braver than to confront illness as Van Gogh did.

A troubled soul since his youth in southern Holland, someone whose family fretted that he could not find a place in the world, he ended up by 1890, in his 37th year, in the strangest and most tragic of situations. He was increasingly recognised – at least among the Paris avant garde – as a brilliant artist. But he was also unquestionably ill. How did his art and illness interact? Was painting a potential cure, or a symptom? Van Gogh contemplated both possibilities. But what he did not do is give up. He looked with pity on other inmates who sat somnolently while he worked. This was no enlightened modern hospital but an asylum of the Victorian age, where the doctor who admitted Van Gogh inadequately diagnosed "epilepsy". In that place he painted this rapturous garden.

In the last few weeks I have been overwhelmed by the relationship between Van Gogh's biography and his genius. The curators of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam have worked for years on a new edition of his letters, five volumes of them, with facsimiles, English translations, copious illustrations: in short, such a complete insight into Van Gogh's life that it redefines him for this century. An exhibition, The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and his Letters, opening at the Royal Academy on 23 January, celebrates this publication.

Reading the new edition of Van Gogh's letters from cover to cover turned out to be a shocking, upsetting, at times frustrating experience that destroyed my previous idea of this great artist. I had previously formed an almost reassuring view of Van Gogh as an intense, troubled, tragic, yet at the same time inspiring man. The sheer mass of peculiarities and sadnesses makes him uttely real and – for all his genius – less easy to empathise with. His achievement was not to conquer illness, but to drag something out of its isolating darkness.

Long before he became an artist, he was a writer. "Theo, I must recommend that you start smoking a pipe. It does you a lot of good when you're out of spirits, as I quite often am nowadays." So writes Van Gogh to his younger brother in one of his very first letters, offering advice on how to fight a melancholy like that which gnaws at him. His earliest surviving letters date from 1872, when he was 19. His very first, dated 29 September 1872, is addressed to Theo – as is his last, dated 23 July 1890. He wrote to other people too – including artist friends such as Emile Bernard and Paul Gauguin, and his sister Wilhelmina, who was herself to spend decades in an asylum. Together these letters amount to a literary work of epic proportions.

It's not just that Van Gogh wrote letters. He poured his heart into them. The long epistles he sent Theo, who worked as an art dealer and was the single greatest emotional and financial prop in Vincent's life, are diaristic explorations of every facet of his life. You smell the very tobacco-laden breath and musty clothes of Van Gogh. The shape of the man these massed words slowly reveal is much baggier and saggier and perplexing than any actor in any film could portray.

Often the silences say the most. A series of letters from 1880 were destroyed by his family for the embarrassing reason that in these months his father was making active plans to have him incarcerated in a psychiatric hospital. This was nearly a decade before the crisis that led to his eventual hospitalisation. Van Gogh's family doubted his mental wellbeing all along. Reading these letters it becomes all too clear that this was why his brother Theo undertook to support him to be an artist. The tensions the letters expose in their relationship – Vincent accuses Theo of not even trying to sell his paintings – suggest that until quite late on, Theo saw his brother's art essentially as therapy. When it became more than that, it was to kill them both – for when Vincent succumbed to his visionary extremes, his brother's health collapsed and he died soon afterwards like a grief-struck spouse.

The copiousness, too, is eloquent. The excess of Van Gogh's need to communicate becomes tragic. It so clearly exceeds what Theo can say in reply, what anyone can say. "Why am I telling you all this? – not to grumble, not to apologise . . ." "I jotted a few things down in the train and am sending you that, just so you can see how my trip went . . ." "I want answer your letter of this morning straightaway . . ." You start to feel these letters constitute his real life, the pen and paper his own real companions. Sometimes he gets a reply, sometimes he doesn't. Always he is alone.

Art saves him. His letters take on a new joy and conviction when he starts teaching himself to draw. The most uplifting letter he ever wrote was sent from Etten, where his parents were then living, to Theo in September 1881. In it, he describes his efforts to draw the local peasants at work and in their cottages. The reason it is so beautiful is that he includes sketches of what he has been doing. These sketches are marvellous – even though he has only recently started drawing, and has no formal art education. He is so manifestly gifted. He is, suddenly, on his way. As he says in the letter, "a change has come about in my drawing . . . I'm no longer so powerless in the face of nature as I used to be."

This is such a good new start, you are crushed that it did not lead to a steady improvement. Instead, he fell out with his family (again), set up studio in The Hague, but alienated his friends there – not to mention Theo, who was paying. His drawing went on getting stronger but there was no parallel conquest of everyday life.

Nor did things improve when he migrated to France. Here, he met the avant-garde – he knew Toulouse-Lautrec and Pissarro, as well as the mercurial, arrogant, uncompromising genius Paul Gauguin, who was already anticipating aspects of abstract art. Then on 20 February 1888 he got off the train in Arles in Provence, where he planned to found a colony for artists, a "studio of the south". The collapse of that dream is the most infamous chapter in his life. After a lot of cajoling from Theo, Gauguin agreed to stay with Vincent, as potentially the leader of the studio. At first they worked together superbly – Gauguin explained his abstract understanding of colour to Van Gogh, and both of them painted blazing portraits and landscapes side by side. But they started arguing, Van Gogh got more and more stressed, and suddenly confronted Gauguin with a razor. That same night he cut off part of his own ear and gave the bloody flesh to a horrified prostitute.

Incidentally, the expanded letters expose as nonsense the ridiculous idea floated last year that Gauguin cut off Van Gogh's ear with a sword. No reader can miss the emotional thread of self-violence in them – and a clear statement of what happened appears in a letter where he actually says, "I . . . wounded myself," while denying that he is a danger to others.

But the letters put this, the central crisis of his life that led to his entering the asylum at Saint-Rémy and from which he never recovered his mental composure, in a deeper perpective. The full correspondence lets you see how spiritually intoxicated he was before Gauguin arrived. Almost as soon as he got to Arles, the red-headed northerner started painting in a new, incomparable way. The sun entered his paints. It got in his head – "I feel fine working outside in the hottest part of the day. It's a clean, dry heat . . . Naturally this induces orange – a face tanned by the sun looks orange . . . my complexion has changed from green-grey pink to grey-orange, and I have a white suit instead of a blue one, and am always dusty . . ."

Vast suns blazing above golden fields, sunflowers engorging light like immense yellow giant stars: his paintings from these months are like hot stones lifted up from a Provençal field. They are fire. Van Gogh came to believe he was mad when he made them.

In letters written after the crisis, he has time for acutely painful self-analysis. "It's funny that every time I try to reason with myself in order to get a clear picture of things – why I came here . . . a terrible horror and terror seizes me and prevents me from thinking." Yet fighting this horror, he starts to ascribe his problems to the very heat and excitement of the region, rather than to a simple falling out with Gauguin. Moreover, the illness is inseparable from the artistic triumph Provence inspired. This is surely a true insight into these rapturous paintings.

Art historians like to claim that Van Gogh's illness had nothing to do with his art's greatness. His letters, though, suggest otherwise. Was the sun simply too much for him? This is simplistic and yet the paintings tell of a great sensual opening up. Van Gogh's inability to form a long-lasting relationship with a woman torments him in his letters. His religious background was forbidding. He certainly was not sexually inactive – his letters reveal at least three lovers and regular visits to brothels – but something deep in him that had never found satisfaction before was released by the Mediterranenan light. It isn't just a calm, rational love of bright colours that we see in his masterpieces. It is more woozy and more brilliant – a place in his mind where he thinks, feels, exists, in pure colour.

The intoxication of 1888 never left him. In the asylum, his colours become more subtle – blues and greens displace the vibrant yellows – but the profundity and insistence of his paintings does not lessen, it grows.

His letters make terrible reading as the tragedy unfolds. The better his painting gets, the worse his bouts of total unreason become. At the asylum he has periods of constant work interrupted by complete breakdowns, after which he cannot remember what happened. Meanwhile, Theo writes about Dr Gachet, a friend of Pissarro and Cézanne whose sympathy for artists might enable him to informally care for Vincent.

Theo is married and a new father, but also ill, and worried about his job. When Vincent finally heads north, his meeting with Theo in Paris apparently disturbs him. He feels guilty about the financial burden he has placed on his brother. He seems not to see – and perhaps Theo doesn't either – that he is on the edge of fame, even of making money.

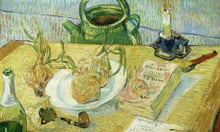

In Auvers-sur-Oise, a village near Paris, the good Dr Gachet keeps an eye on him. He goes on painting, painting so well. Deep blues and blacks and vegetable greens. The colours of the north, now – the colours of rain. He includes a sketch of one of his new paintings, showing the garden of the landscape artist Daubigny, in a letter he sends to Theo on 23 July 1890. In a postcript after the "Yours truly, Vincent" he adds an account of the colours in his painting for Theo to imagine them:

"Foreground of green and pink grass, on the left a green and lilac bush and a stem of plants with whitish foliage. In the middle a bed of roses. To the right a hurdle, a wall, and above the wall a hazel tree with violet foliage.

"Then a hedge of lilac, a row of rounded yellow lime trees. The house itself in the background, pink with a roof of bluish tiles. A bench and three chairs, a dark figure with a yellow hat, and in the foreground a black cat. Sky pale green."

In French the last words are "Ciel vert pâle" and then a brown ink full stop. Three days after sending this, his last letter, he shot himself under the pale green sky.