Even the title of Tate Modern's new exhibition, Van Doesburg and the International Avant-Garde: Constructing a New World, seems to go on and on. The amount of stuff here is daunting. There are tiled floors for holiday homes, back-lit geometric stained-glass windows (based on a woman's head and the fugues of Bach). There are vitrines filled with magazines, letters and notes; chairs and lamps, elegant nightclub ashtrays and designs for Dutch cheese wrappers; architectural models for houses and a nightclub-cum-cinema complex in Strasbourg, as well as endless, endless paintings.

Under the influence of Wassily Kandinsky, and on the eve of the first world war, Theo van Doesburg painted target-like cosmic suns, erupting penumbras of colour, and a vacuous-looking red-cheeked face with gormless button eyes, which he called Girl With Buttercups. His subsequent mobilisation in the Dutch army seemed to cure him of Kandinsky's half-baked spiritual claptrap and this sort of whimsy – but not the shared aim to make a new art for a new century. Wagner's Lohengrin and the operatic ideal of the gesamtkunstwerk (total artwork) provided Van Doesburg's art with big ambitions. He was also a born organiser, a networker, who always wanted to see himself in an international rather than a local Dutch context. He was a thoroughly modern artist: on the one hand, he pursued an art of increasing aesthetic purity and hygiene, even reducing a picture of a cow to a series of geometric blocks; and on the other, he wrote dadaist poems of startling scatological and blasphemous verve and obscenity.

For a while, Van Doesburg's art looked just like Mondrian's, and the two hang together here, one the great painter, the other an artist who never stopped moving, and who tried his hand at poetry, advertising, architecture and design, theorising and play-acting; he immersed himself in the various movements and machinations of the avant garde. Seeing Van Doesburg in the company of Mondrian and Kurt Schwitters, Hans Arp, Jean Hélion, Raoul Hausmann and Tristan Tzara is to see an artist on the run in the 20th century.

Everything lies on the surface

The proliferating "isms" of the 1920s – neo-cubism, futurism, neo-plasticism, constructivism, dadaism, to name but a few – are confusing. All the divergent philosophies and ruptures over seemingly inconsequential issues, the strident manifestos and depersonalised and interchangeable artworks, are frequently less dramatic than the lives and friendships that produced them. This fascinating show is perhaps more fun than it ought to be because it succeeds in drawing out the latter. One can walk through admiring here a sideboard by Gerrit Rietveld (it looks like a Rennie Mackintosh, coupled with a Frank Lloyd Wright), pausing gratefully over a Mondrian with an empty grey centre, laughing at the words "merde" and "caca" graffittied over a postcard portrait of German expressionist Herwarth Walden. One can enjoy the naive early abstract animation of a Hans Richter film, or worry over the developing use of the horizontal and the vertical, and the disruption caused by the use of a diagonal. And were those neo-plasticists really allowed to use purple?

In 1902, at the age of 19, Christian Emil Marie Küpper first adopted the name of his stepfather and became Theo van Doesburg. Later he toyed with using Küpper as the first of a number of pseudonyms or noms de guerre. He published articles under the name Pipifox, briefly, and became a dadaist called IK Bonset. He even got his third wife, Nelly van Moorsel – wearing a convincing moustache, and with pipe in mouth – to pose for a portrait as the mysterious artist. Bonset could do what Van Doesburg could not.

Van Doesburg's leanings towards iconoclastic, anti-art dada – seemingly at complete odds to the purity and rigour of his own art and beliefs – have been described as "guilt-ridden", and "quasi-clandestine". He produced a dadaist magazine, Mecano, alongside his impeccable de Stijl (the Style) magazine, which was devoted to a theory of abstraction. He said he wanted to "splinter himself" and explore different identities, the irrational as well as the rational. (One might well wonder how far all this Jekyll and Hyde splintering went, in the artist's private life as well as his public.)

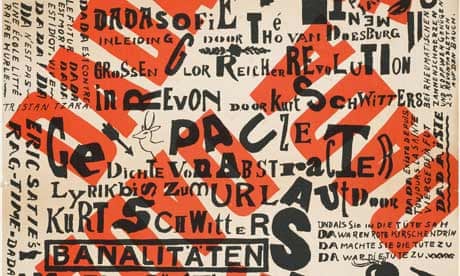

Rational and rectilinear, Van Doesburg's paintings ditched all representation and illusions of depth, including foreground and background. Everything lies on the surface. Mathematical progressions and the use of the grid allowed him to plot his compositions in relation to the rectangle or square on which they sit. He came to believe that art "should not contain any natural form, sensuality or sentimentality", and that the painter's technique "should be mechanical rather than 'impressionistic'". Individualism, he felt, got in the way. The pleasures of his art are austere, and he lacks even Mondrian's musicality. All this appears at odds with Bonset's all-over-the-place, cluttered dada posters, and the manifesto in which he spits on God, Jesus and Marx and "on the knicknack and papier-mache artists who want to make a world of soft chocolate and perfumed shit". "Life," Bonset concludes, is "a venereal disease".

Van Doesburg, meanwhile, once wrote that "life is an extraordinary invention". His play with selves and artistic personalities might be compared to those of the great Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, who invented several characters who each wrote in a different manner and voice. Behind all this play, there is a recognition that artistic personality and authenticity are guises, however deep-seated they appear. There is nothing natural about it, and being an artist has long been an act of self-invention. Marcel Duchamp, inventing his female alter ego Rrose Sélavy, said he believed more in the artist than the art.

Modernism is still heady stuff, even if we think it's over. No one even uses the word "postmodernism" much any more, and there seem to be no more big, or even small isms to worry about or be confused by (stuckism, for what it's worth, isn't a movement but a publicity stunt). There's no mainstream, apart from a tedious, almost universal fixation with celebrity and art as entertainment; there is no artistic gambit that hasn't been tried or can't find a public or a market, somewhere. That in itself is confusing. Whatever happened to high ideals? How would Van Doesburg fare today? I think he'd accommodate and fit in pretty well. He was a smart guy, a bit of an operator.

A rigorous goodbye

One can also see how Van Doesburg's last and most rigorous phase, art concret, which called for works to be self-referential and absolutist – "entirely designed and formed by the mind prior to execution" – might even lead towards conceptualism. Art's all in the head, anyway. While Van Doesburg expunged his art of outside references and all expression, art concret led not to a dead end but to minimalism's boxes, cubes and literal forms. It also inspired the great flowering and playfulness of the Brazilian neo-concretist art of the 1950s and 60s, the gliding planes of suspended colour, the flowing banners and cloaks of Hélio Oiticica, and the manipulable, mysterious forms of Lygia Clark. Had he not died of a heart attack in his late 40s, perhaps Van Doesburg's art would have become even more emptied out; perhaps he would have turned his attentions fully to objects rather than paintings. Who knows. He might have had to invent several more pseudonyms to cope with all the possibilities.