The Hero Gen Z Needs

Snoopy can’t help but feel overwhelmed in a tumultuous world. Sound familiar?

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

Snoopy was everywhere when I was growing up, in the early 2000s. On TV, the cartoon beagle appeared as a float in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade and starred in the holiday specials my family watched; in real life, his statues were all over Saint Paul, Minnesota, a hometown I share with the Peanuts creator Charles Schulz. After I left for college, Snoopy largely disappeared from my life. But recently, I’ve started encountering him all over again, on social media.

The TikTok account @snooopyiscool, also known as Snoopy Sister, went viral earlier this year and has more than half a million followers. Other Snoopy videos on the app regularly rack up thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of views. This online resurgence, primarily among young people, has mostly been fueled by short, shareable Peanuts clips set to surprisingly apt contemporary music. In them, Charlie Brown’s intrepid pet beagle tags along on the kids’ adventures—they often face some sort of problem but aren’t always left with an easy solution. Sometimes Snoopy is a help, and sometimes he’s a hindrance; other times, he’s on his own adventures. Regardless, Snoopy has always been defined in part by how emotional he is. Some fans say that his personality speaks to their inner child: He plays pretend and dreams big, while finding joy in little wins such as receiving a full bowl of food. But Snoopy’s grand feelings also reflect his existential side—a reminder of the comic’s original gloomy tone, the perception of which was softened and sanitized over subsequent decades. It seems that a new generation is finally seeing Snoopy for who he really is.

Despite featuring an adorable dog and his rich fantasy life, Peanuts always had bleak philosophical themes. In the early years of the strip, which first ran in 1950, cultural critics called Schulz a “pop existentialist,” according to Blake Scott Ball, a history professor at Huntingdon College and the author of Charlie Brown’s America: The Popular Politics of Peanuts. The comic “was about the difficulty of existing as a regular human being in the 20th century ... just how hard it is to handle the immensity of problems that faced us, and hold all that together with your daily concerns,” Ball told me. Schulz posed serious questions in his stories—about armed conflict, for example, in the era of acute atomic-bomb fears and the beginning of the Vietnam War—but left the answers unclear. In one scene, Snoopy wears his aviator outfit and compares being trapped in his doghouse to being imprisoned.

Snoopy, despite his broad imagination and silly antics, had personal troubles too. Ball pointed to one edition of Peanuts where Snoopy cries on Mother’s Day because he’s separated from his mom. After helping him send her a card, Charlie Brown muses about how holidays can be difficult for everyone. When Schulz adapted his comics for the animated specials in the 1960s, Snoopy became more anthropomorphic and expressive, and embarked on his own fantastical B-plots. He didn’t speak, instead communicating with noises, including whining and cackling. Still, his angst remained.

Many of today’s young people likely first experienced the Peanuts characters through the animated specials, which explains why those clips trigger a specific nostalgia. But the televised format also lends itself to TikTok. Unlike in the comics, Snoopy in animated form doesn’t have thought bubbles to explain his feelings, so he resorts to over-the-top physicality. When a female poodle pecks him on the cheek, he blushes, his ears standing straight up, then falls into a swoon, as cartoon hearts appear over his head. He sobs loudly at a party but still takes comfort in a small moment of affection—a high five—with a friend, who is also crying. His ability to convey these sentiments, all without saying a word, might have a particular appeal for Zoomers, who have been performing big emotions online since they learned to type. For them, Snoopy has become something of an unexpected avatar for the “internet sad girl”—a certain online persona, raised on Lana Del Rey lyrics and Tumblr, that revels in her sorrow.

The key to Snoopy’s popularity now seems to go beyond his cuteness. Over the years, the character had been turned into a mascot for organizations such as MetLife and NASA. The Snoopy statues in my hometown—which I’d see in the airport, the library, my high school—served both as a tribute to Schulz and as an adorable character for kids to admire. What rings especially true today, however, is the dog’s tumultuous inner life. If the character’s commodification has at times flattened him, his online rebirth in the Zoomer era emphasizes his emotional oscillation, making him feel truer to the original Peanuts and to today’s realities.

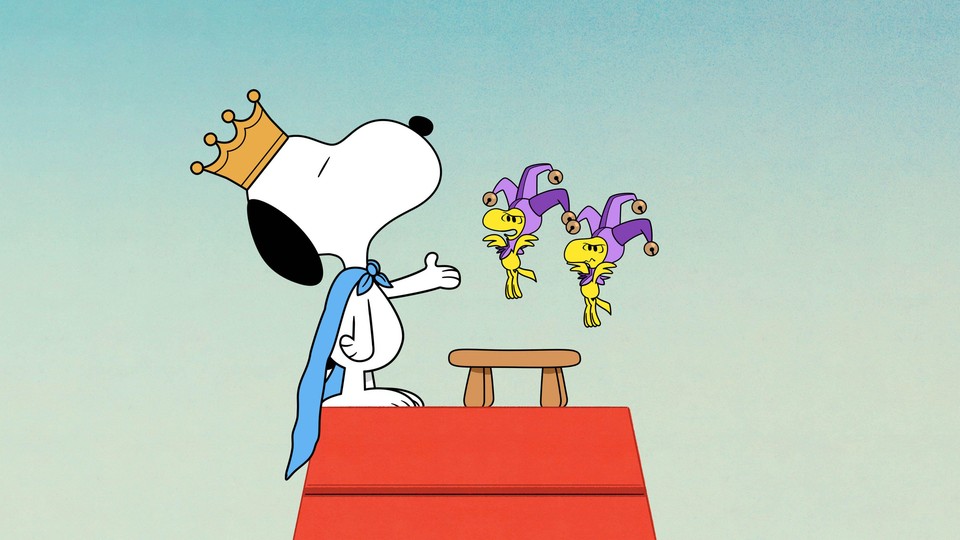

This is exemplified by the more contemporary soundtrack to those edited TikTok clips, added over scenes from the cartoon or simply played over a static video of a Snoopy doll. Clips that show Snoopy at his lowest—when he’s taking a walk alone in the rain or lying mournfully on top of his doghouse—are paired with songs such as “Creep,” by Radiohead; “Kill Bill,” by SZA, and “Ketchum, ID,” by Boygenius. Each video communicates overwhelming isolation, anger, sadness. But it’s not all bad. The sad-girl persona tends to be interpreted as gratuitously melancholic, but in actuality, it can simply encapsulate the enormity of one’s feelings—positive or negative. Snoopy gets this. For all his lonely moments, he also has joyful ones. He dances, laughs, and enjoys a good meal. He imagines himself as a writer, a fighter pilot, or just “cool.” When these Snoopy clips recirculate, they feature upbeat hits such as “You Wish,” by Flyana Boss, a song that embodies brazen confidence.

In Sarah Boxer’s 2015 Atlantic article on Snoopy’s legacy, she describes his behavior as a defense mechanism: “Since no one will ever see you the way you see yourself, you might as well build your world around fantasy, create the person you want to be, and live it out, live it up.” As Zoomers come of age, they face a barrage of seemingly hopeless climate and political catastrophes. In the face of this, it’s no wonder Snoopy has become a hero. Sometimes, people just want to throw their hands up at the immensity of the world and retreat to a controlled, interior one—a doghouse of their own—from which they can feel their emotions as much as they want.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.