arts

Lucky Luke, a World-Famous Cowboy From Flanders

For a Flemish cartoonist, a western is not an obvious genre. And yet Maurice De Bevere – who would have turned one hundred this year – created Lucky Luke. The most Belgian of all comic strip cowboys has enjoyed international success since his debut in 1946, with millions of albums sold. Even today, a quarter of a century after the death of his creator.

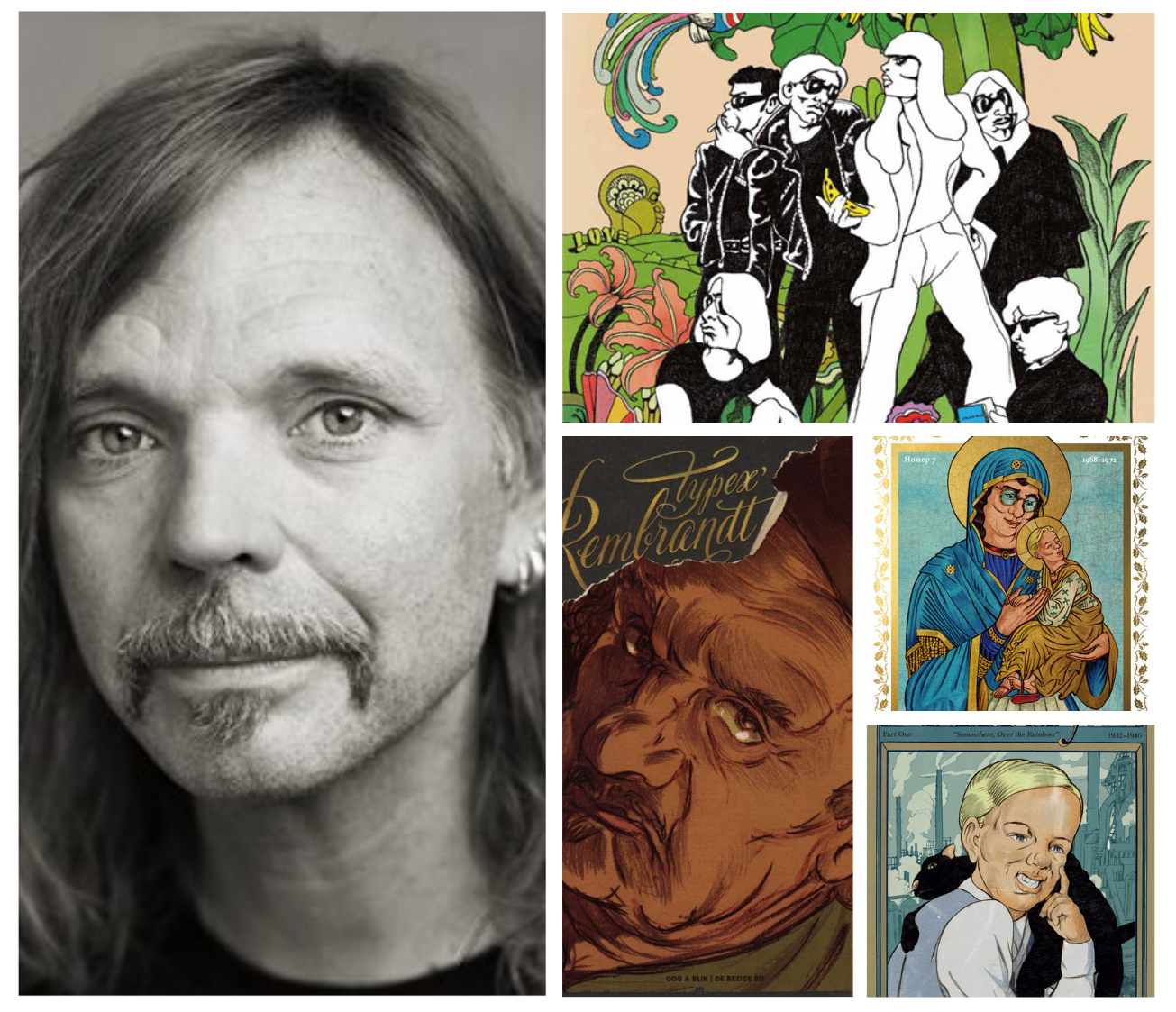

Maurice De Bevere aka Morris © website Huberty & Breyne

In 1923, nothing hinted that the newborn member of the De Bevere family from Kortrijk would one day achieve fame with a humorous western cartoon. Maurice’s parents had a pipe factory. The advantage of a wealthy family is that the children have no shortage of paid entertainment. For example, there was a projector at the De Bevere residence on which animated Felix the Cat films could be played. Like the rest of the Western world, Maurice enjoyed Disney’s feature film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and, more so, the Popeye cartoons by Max Fleischer, based on Elzie Segar’s cartoon characters.

Many children’s magazines were created during Maurice’s childhood years. He read them in different languages. Tintin’s first adventure, Tintin au pays des Soviets (Tintin in the Land of the Soviets), made a decisive impression in 1929, he would later say. Hergé’s story may have planted the first seed of his career. Maurice was also very fond of the Mickey Mouse Weekly, which he read in English. Walt Disney and Floyd Gottfredson, the artists of the Mickey Mouse comics, would later graphically influence the first Lucky Luke stories.

From cartoons…

During the war, Maurice enrolled to study law at the Catholic University of Leuven, but he actually wanted to become a draughtsman. He followed a training course by correspondence and was able to start working at C.B.A., a small animation studio in Liège that essentially owed its existence to the ban on American cartoons imposed by the occupier. De Bevere, who henceforth used the pseudonym Morris, met André Franquin, a young man his own age, who would later create the Spirou & Fantasio adventures, Gaston Lagaffe (Gomer Goof) and Marsupilami.

Sketches by Morris for 'Le Cadeau de la fée', 1946 © Lucky Comics, 2023

The self-assured Morris, a well-dressed jazz lover from a wealthy background, took the insecure Franquin in tow when their animation studio folded. The two young men would focus on comic strips – since they were easier to produce than cartoons – and partnered with Dupuis, which published the bilingual magazine Spirou/Robbedoes weekly again after the war.

Morris had previously worked for the Dupuis weekly magazine Le Moustique and its Dutch-language counterpart, Humoradio, where humorous illustrations were always welcome. Those drawings were the only long-term engagement in his professional career that had nothing to do with Lucky Luke. Morris continued to provide illustrations for publisher Dupuis’ general magazines until 1956.

…to comic strips

His comic strip project took shape in 1945. Morris had always loved westerns, a major genre in the cinema of the 1930s and 1940s. He decided to make a funny western comic strip, since there was none in Spirou up until that point. According to his later wife Francine, the presence of horses also played a role, since Morris liked to draw them. The first Lucky Luke story (Arizona 1880) was published at the end of 1946. It was a slapstick western with many action scenes; the polished drawing style revealed Morris’ background in animation, just like the four fingers on the hands of his characters.

The first page of the first Lucky Luke story, 'Arizona 1880', published in 1946 © Lucky Comics, 2023

His comic strip hero soon took on more character. He got his lanky look from Gary Cooper. Morris was inspired by his 1947 film Along Came Jones. Although the publisher wanted to make Lucky Luke an exemplary hero, Morris made him smoke like a chimney. Cooper’s character, Melody, sings, among other things, the traditional “Poor lonesome cowboy”, which Luke would later repeat regularly. Singing cowboys were actually quite common in the cinema of that time. Actor Gene Autry’s cowboy songs were very successful and made him incredibly wealthy.

At the end of each adventure, Lucky Luke sings the song 'Poor Lonesome Cowboy'. © Lucky Comics, 2023

America

Dupuis sent its young cartoonists to Jijé to learn the comics trade. At that time, Joseph Gillain (the comics artist’s full name), was responsible for the Spirou & Fantasio comics and for other important Spirou series such as Jean Valhardi. Mentor Jijé took Morris and Franquin under his wing, and together with Willy Maltaite, a young cartoonist who lived with him, they travelled to Mexico and the United States. During their stay on the other side of the Atlantic, the work of the four cartoonists showed so much mutual influence that a typical comic strip style for the magazine Spirou came about. In French, it was known as “l’École de Marcinelle” (Marcinelle School), after the municipality near Charleroi where Dupuis was located.

In the back row, from right to left: Francine De Bevere and Morris, René Goscinny (with bow tie) and, in the foreground, Harvey Kurtzman in New York, circa 1951 © Lucky Comics, 2023

From 1949 onwards, the cartoonists returned to Belgium one by one, but Morris stayed in New York until 1955. While he continued sending his Lucky Luke pages to Belgium, he published a children’s book there and met Harvey Kurtzman, who was at the cradle of the satirical comics publication Mad Magazine. The hugely successful magazine parodied films and TV shows, among other things, and had a lasting effect on the humour in Lucky Luke. Morris also liked the caricatures in the magazine, which he used not only in his comic strip, but also in the stage reports of the Tour de France that he made for the newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws in the early 1950s.

The dream scriptwriter

Another New York contact who would have an even greater influence on Morris’ work was René Goscinny, a French Jew who grew up in Argentina. Morris met him in 1950 and appreciated his humour. Five years later, when they were both living in Belgium, they started working together on Lucky Luke. Their first album was De spoorweg door de prairie (The Railroad Through the Prairie), inspired by Cecil B. DeMille’s 1939 film Union Pacific. Initially, the writer’s name was not mentioned on the albums, but that changed when Asterix made Goscinny a star.

'De spoorweg door de prairie' (The Railroad Through the Prairie) was the first Lucky Luke album for which Morris had collaborated with Goscinny. © Dupuis

For Morris, the main benefit of their collaboration was that it allowed him to stop all his other assignments and focus exclusively on Lucky Luke. In some years, he drew as many as three stories, while he previously had difficulty making just one Lucky Luke per year. Together, Morris and Goscinny created a fleshed-out universe with memorable characters such as Billy the Kid, Calamity Jane and, of course, the Daltons, the cousins of the original brothers Morris had killed off in Vogelvrij (Outlawed). Inspiration came more and more from historical stories about the Wild West, but also from the western films that were made about it, especially in the 1930s and 1940s.

Scriptwriter René Goscinny and Morris in Amsterdam, 1971 © Wikipedia

A style of his own

Graphically, Morris quickly developed a style that differed from the Marcinelle School. He realised that comics required a completely different approach than animation films and experimented with page layout and ways to suggest movement. He did away with excess scenery and used bold colouring to enhance the readability of his stories.

For an author who took his form of expression into such consideration, it isn’t surprising that from 1964 to 1967 he was given a section in the magazine Spirou together with journalist Pierre Vankeer, entitled Neuvième art (Ninth Art). They regularly presented classic comic strips that were hardly known at the time. The term “ninth art” was not their own, but Morris and Vankeer introduced it to a wide audience as an honorary title for the comics medium.

A Long Way from Home

Although the Lucky Luke strip became increasingly popular, Morris still occasionally encountered backlash. Due to the 1949 French law for the protection of minors, an author of westerns had to, in any case, be wary of censorship. Unlike other well-known series such as Blake and Mortimer, Buck Danny or Alex, a Lucky Luke album was never banned, but that was also due to the prudence of the publisher.

The frivolous barmaids in 'Dalton City' showed that Goscinny and Morris felt liberated. © Lucky Comics, 2023

For example, they initially omitted a page from the album Billy the Kid, in which Billy is sucking on a revolver as a baby. Morris found these interventions annoying and regretted that his publisher did not want to bring out a hardcover Lucky Luke, like most other French editions of comics in Spirou. It led to a break in 1968. Lucky Luke moved to the French publisher Dargaud and to the magazine Pilote, led by scriptwriter René Goscinny. The frivolous barmaids in Dalton City (the first story for Dargaud) alone showed that the authors felt liberated by the change.

Commercially, the new publisher also proved to be a hugely successful move. The 1970s were the decade of the big breakthrough, partly due to the two full-length animated films that Goscinny wrote and directed himself, Daisy Town and De ballade van de Daltons (The Ballad of the Daltons). Even former publisher Dupuis sold tens of millions of older albums in the series in the 1970s – more than in all previous decades combined.

Poor Lonesome Cowboy

The sudden death of René Goscinny during an exercise at the cardiologist in 1977 was a major setback for Morris, who subsequently never relied on a single scriptwriter again. He didn’t only look to the French-speaking comics world for replacements. At that time, Lucky Luke was pre-published in the Dutch comics magazine Eppo, where Morris met scriptwriters Martin Lodewijk and Lo Hartog van Banda. They later produced some of the more memorable albums since Goscinny’s death, such as Fingers (1983).

The same album marked a milestone in the series: under pressure from American studio Hanna-Barbera, which would produce the first Lucky Luke cartoon series, the cowboy gave up tobacco, and ethnic stereotypes – such as the Chinese with their launderettes or sleeping Mexicans – disappeared.

Morris next to the statue of Lucky Luke in the library of Kortrijk, the cartoonist's hometown, in 1997. © City of Kortrijk

As of 1990, Morris self published with Lucky Productions, but after nine years, the company was reincorporated into Dargaud. A spin-off about the young Lucky Luke – Kid Lucky – was stopped after two albums because the tone of the series was too mature. For a long time, Rantanplan (about the Daltons’ stupid dog) remained the only ongoing spin-off series. The 1990s brought awards and recognition. Europe’s premier comics festival, Angoulême, awarded Morris a special prize for the festival’s twentieth anniversary. In Belgium, statues and murals in honour of the Lucky Luke series appeared in Brussels, Kortrijk, Charleroi and Middelkerke.

Ceramic wall representing the main characters from Morris' Lucky Luke comic series : including Rataplan, his horse Jolly Jumper and the cousins Dalton. Made in 1996 on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the comic series, Parc metro station in Charleroi. © Wikipedia

The cowboy lives

Thanks to some thirty translations, Lucky Luke is one of the world’s best-selling European comics. This is the Serbian versian of the album 'Daisy Town'. © Last Dodo

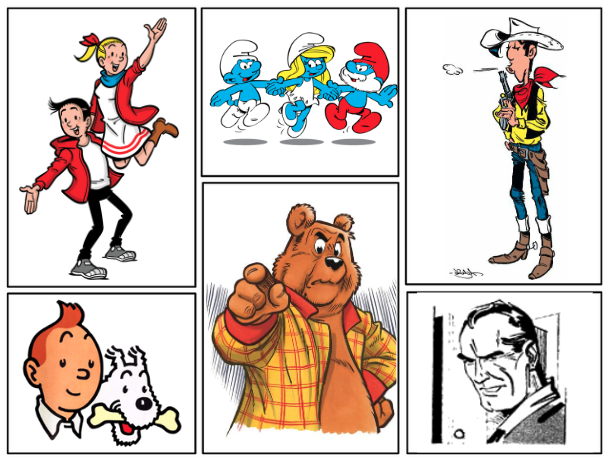

When Morris died in 2001, Lucky Luke was a rock-solid comics brand. It appeared in Spirou at a time when that magazine was leading in Europe. It was also where The Smurfs, Gomer Goof and Marsupilami started their international success story. Subsequently, various internationally produced cartoon series, as well as live action films and games, have strengthened the fame of the most Belgian of all cowboys among a very broad audience. Thanks to some thirty translations, from Icelandic to Turkish, Lucky Luke is, together with Tintin and Asterix, one of the world’s best-selling European comics.

'Wanted Lucky Luke', a reinterpretation of the series by Matthieu Bonhomme © Dargaud

Almost a quarter of a century after Morris’ death, his 73 albums are still being reprinted. Together with various scriptwriters, his former assistant Achdé has already created ten Lucky Luke albums “after Morris” with ditto success. More interesting are the reinterpretations of the series by established authors, of which De moordenaar van Lucky Luke (The Man Who Shot Lucky Luke) and Wanted Lucky Luke, both by Matthieu Bonhomme, are the most fascinating. The son of a pipe manufacturer from Kortrijk continues to inspire authors and readers with a medium that was initially his second choice, but of which he ultimately changed the course.

- Morris 100: Vader van Lucky Luke (Morris 100: Father of Lucky Luke), 2 to 17 December, Kortrijk City Hall

- Morris – 100 jaar oud, 100 kunstwerken (Morris – 100 years, 100 works), 1 December to 27 January, Galerie Huberty & Breyne, Brussels

Post comment

Sign in