- A new design for a bionic eye packs millions of custom-grown nanowires into an aluminum shell.

- Bionic body parts are cutting-edge technology, and this eye could surpass human ability.

- Instead of fighting the spherical nature of human eyes, these researchers began with a sphere.

Scientists say they’ve made a bionic human-compatible eyeball that has nearly 50 times more “sensing” nanowires than there are optic cells in the human retina. The researchers suggest the eventual product could see farther and in finer detail than the human eye, with potential to restore sight or even surpass healthy normal sight—including seeing in the dark.

In a new paper in Nature, the scientists explain the challenges of biomimetic (life-imitating) vision. Characteristics like “extremely wide field of view, high resolution and sensitivity with low aberration” are required of any imitation eye, they explain, but “the spherical shape and the retina of the biological eye pose an enormous fabrication challenge for biomimetic devices.”

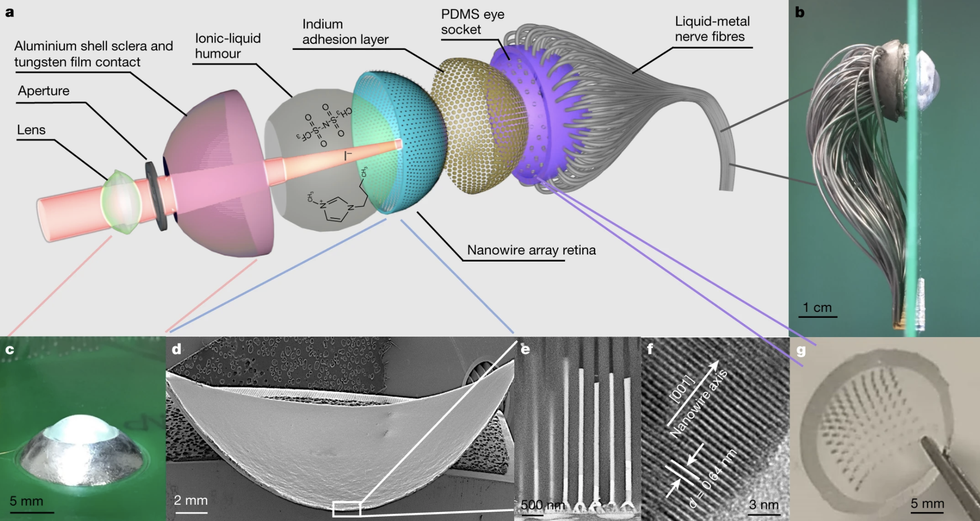

Their solution comes in the form of a densely packed hemisphere of nanowires. The nanowires receive light, measure things like its spectral frequency, and send the information through some more wires that mimic the visual cortex. But the real breakthrough is in how the artificial retina is assembled: millions of nanowires are grown inside nano-size pores in a spherical aluminum shell.

The nanowires are made of perovskite, a crystalline mineral valued in solar cells for its photoreceptive qualities. (In fact, the term “perovskite” has been genericized into a whole class of compounds with similar qualities but made with different combinations of elements.) Making solar cells using traditional manufacturing is a far cry from generating nanowires in situ, and in this case, the novel “manufacturing” makes all the difference.

Proponents of robotics often argue it’s silly to make anthropomorphic machines that, for example, walk upright on two legs when that’s much harder to design than other forms of locomotion. But the human eyeball—the spherical photoreceptive eyeball in general, shared by many higher-order animals—is so functional partly because of its physical structure, in a way scientists are eager to emulate.

In the 2014 miniseries Cosmos, cosmologist Neil de Grasse Tyson explained the evolution of the human eye as a direct consequence of our origins in the sea.

“Want to know what the world looked like to a light-sensitive bacteria?” he wonders, before showing a side-by-side diagram where “creature’s eye view” is just a single broad, bright area in an otherwise dark field. The same way we put on sunglasses against the bright sun, primordial bacteria sunk into the sea to avoid damaging UV light. And over time, the spherical eyeball with a “pinhole camera” to let in a very small amount of light evolved.

“We like to think of our eyes as state of the art,” de Grasse Tyson explains, “but 375 million years later, we still can’t see things right in front of our noses or discern details in near darkness the way fish can.”

Now, an imitation eye packed with 460 million custom-generated nanowires could take human vision forward at last. With higher “resolution” (from so many more sensors) and the most advanced materials, these scientists have suggested a way to expand what we consider the visible spectrum of light to begin with.

Caroline Delbert is a writer, avid reader, and contributing editor at Pop Mech. She's also an enthusiast of just about everything. Her favorite topics include nuclear energy, cosmology, math of everyday things, and the philosophy of it all.