For more than a century, Popular Mechanics has provided life-saving advice for outlasting storms, surviving outdoors, and preparing for disaster. Find out how to survive anything right here.

On August 14, 2011, when a Japanese student slipped off a guardrail above Horseshoe Falls, Niagara's postcard waterfall, she plunged 180 feet. While searching for her the next day, authorities found the body of another victim of the falls, an unidentified man.

Despite the multiple reports during that deadly summer (and the fact that accidentally going over a waterfall makes for good movie drama), the odds of accidentally going over are remote. But could you somehow improve your chances of surviving a plunge over a waterfall like Niagara?

⚠️ Never purposefully jump off a waterfall, you will likely be seriously injured or even die. The following tips are meant to aid in your survival if you happen to find yourself staring down a waterfall with no means of escape.

The Threats

Six million cubic feet of water rush over the falls every minute during peak daytime hours (upriver dams change the volume). The rapids above the falls are clocked at 25 mph, and up to 68 mph over the brink. "I can't think of any way to survive that except luck," says Malcolm Cooper, chairman of the Hawaii Masters Swimming Association. He grew up in Buffalo, N.Y., and knows Niagara well. "Basically, you're going to hit rocks."

But rocks aren't the only threat. If you miss them, the next is bubbles; the plunge pool under a waterfall is like big surf. "There's so much air mixed in with the water that you can't swim in it. Everything goes black in big surf because the sunlight is blocked out by the bubbles. In Niagara Falls, that would definitely be the case," Cooper says.

If you survived the bubbles, the turbulence and darkness underwater would probably disorient anyone who survived the plunge from Niagara Falls. "When you're washed in big waves, you can't tell which way is up," Cooper says. "You're getting pushed around by water. You just have to hope that you get pushed up." Debris could be another killer. "The risks are all the stuff that's around you. You get bashed underwater. That's why kayakers wear helmets," Cooper says.

Finally, if you manage to surface, you can float even in a bruising current. But then you have to worry about the cold. Niagara's waters are in the 30's (Fahrenheit), and Cooper says that gives you about 3 minutes before you black out. The United States Search and Rescue Task Force is a little more optimistic. The shock of sudden entry into cold water can trigger a heart attack, even in healthy people, but if you survive that, the task force gives you less than 15 minutes in water that is freezing or below, and 15 to 30 minutes in water up to 40° F.

The Tips

In the face of so many dangers, it's difficult to draw up a game plan. But Steven Labov, the task force's chief, made a short list of tips for surviving a fall.

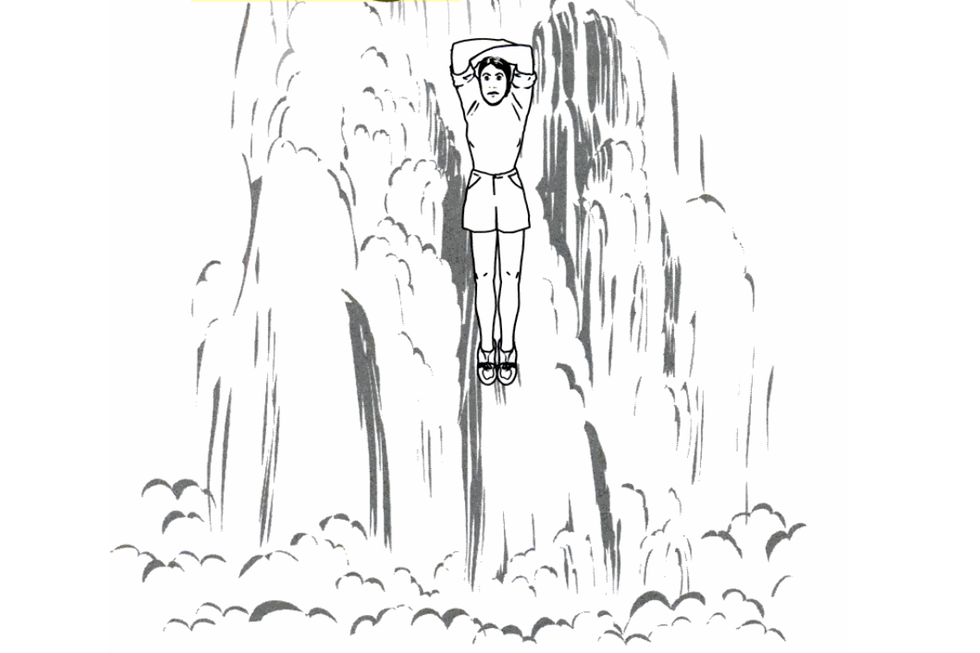

First, he says, do not panic. Take a deep breath just before you go over the edge. Go feet first to avoid head injury. As you're falling, tighten your muscles, wrap your arms around your skull to shield it, and cover your nose with the crook of your elbow. Just before you enter the plunge pool, press your legs together, tighten your gluteals and close your eyes and mouth to make yourself water tight. When you surface, swim downstream as soon as possible to avoid the falling water. If you just fell in front of a crowd of tourists, help should be on the way.

And finally, Labov says, "adrenaline will help you."

A Few Helpful Hints From the April 2003 Issue of Popular Mechanics

Say you're swimming in a river and you suddenly get caught by the current. You've swept downstream. Dead ahead is a waterfall. You kick and flail your arms with all your might, but to no avail. There is no way to avoid going over. What should you do?

- Take a deep breath: Do this just before you go over the edge because you probably will not have much control while you're in the air, and the water maybe deep.

- Go over the falls feet-first: The biggest danger in going over a waterfall is hitting your head on something underwater and being knocked unconscious. Even if you hit the water feetfirst, there is a risk or broken limbs. Squeeze your feet together and remain vertical.

- Jump out and away: Get away from the falls just before you go over. You want to avoid hitting rocks directly at the bottom of the waterfall.

- Put your arms around your head: Start swimming upon immediately hitting the water, even before you rise up to the surface. Swimming will slow your descent to a degree.

- Swim downstream: It is essential that you avoid being trapped behind the waterfall or on the rocks underneath.

Even without Labov's advice, three people have slipped or jumped into the falls without protection and lived to tell about it. In 1960, Roger Woodward, a 7-year-old, fell over the falls wearing a life preserver and survived. In 2003, Kirk Jones, 40, took the plunge without even a flotation device. And in 2009, an unidentified man survived the fall and swam until rescuers saved him.

We'll never know how closely these Niagara survivors followed Labov's prescriptions. However, if anything saved them, it might have been entering the water at the best angle, feet-first. That's how most high-divers do it, and many world records meet or even exceed Niagra's 180-foot height, so it's not impossible to survive.

Overall fitness matters, too. High diving, even at lesser heights, requires practice and a body that can take a beating. The World High Diving Federation explains that as divers enter the water, their underwater body parts are at the highest rate of deceleration while the part of the body that is still dry is at full acceleration. "The athlete must be at maximum strength and muscle-tightness upon entry, to avoid compression or contortion of the body or its parts," the association says on its website (which explains Labov's advice on tightening your gluteals).

If the body isn't at maximum strength to withstand those forces, or if the fall happens from so high that a human body simply can't withstand them, the results can be gruesome. In 1968, Richard Snyder published a study called Fatal Injuries Resulting from Extreme Water Impact, a medical report for the Federal Aviation Administration. (Given the prevalence of commercial air travel over water, the FAA wanted to know about "human survival tolerances in water impacts.") Snyder looked at the autopsy results from 169 people who jumped off San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge in a 29-year period. That's a leap of about 250 feet, or nearly 40 percent higher than the fall from Niagara.

A "Tiny" Waterfall, a Dangerous Risk

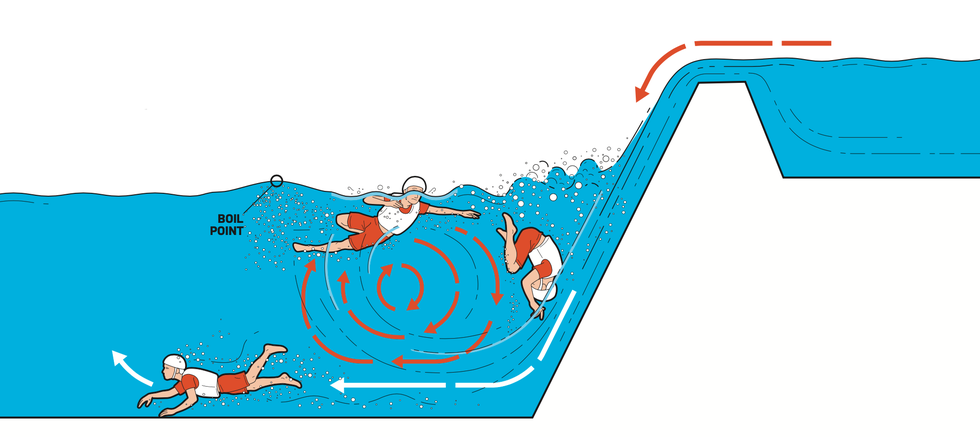

Found on small or moderate-size streams and rivers, these tiny waterfalls are really low-head dams used to regulate water flow or prevent invasive species from swimming upstream. “They’re called drowning machines because they could not be designed better to drown people,” says Kevin Colburn of American Whitewater, a nonprofit whitewater preservation group. To a boater heading downstream, the dams look like a single line of flat reflective water. But water rushing over the dam creates a spinning cylinder of water that can trap a capsized boater.

Curl up, drop to the bottom, and move downstream if caught in a hydraulic. “It’s a counterintuitive thing to do, but the only outflow is at the bottom,” Colburn says. Surface only after you’ve cleared the vortex near the dam.

The impact crushed the rib cages in more than half of the jumpers, Snyder reports. Hearts and blood vessels ruptured from within after a sudden pressure change, but most of the organ damage was probably caused by shards of shattering bone and cartilage. Fractured ribs penetrated the lungs in three quarters of the jumpers, livers ruptured in more than half, and 30 percent had brain injuries. Finally, 45 of the jumpers (26.6 percent) may have lived through the impact but drowned to death.

However, Snyder also found that body position at impact might be the more critical factor. He cited data showing that people have survived an impact with water at speeds of 100 to 115 feet per second if they entered feet first, 97 feet per second if they entered head first and only 87 feet per second if they hit the surface on their sides or bellies. Nevertheless, the key stat was still grim: At the time of his 1968 study, 99.3 percent of known Golden Gate fallers or jumpers died from their jumps.

So Cooper was probably right from the start: To survive any fall into the water from such great heights, you have to be lucky. It may help to be young, strong, and trained in cliff diving, but the best survival tip is to stay off the guard rails.

Rob writes about technology, medicine and solutions for global development. He lives in Colorado among a herd of his own children, and he sometimes tries to play the ukulele. Besides Popular Mechanics, you can also find his work at Reuters and a non-profit called Engineering for Change.