IT IS LATE morning in Port-au-Prince, and the Haitian psychiatrist’s chauffeur has arrived to drive us up north to meet two zombies.

Narcisse visits the tomb where he was buried in 1962. He claims to have spent three days underground.

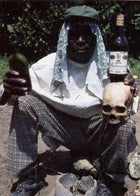

Narcisse visits the tomb where he was buried in 1962. He claims to have spent three days underground. A madiawe, or poison-maker, prepares to grate human skull for his potion.

A madiawe, or poison-maker, prepares to grate human skull for his potion.We are ready. Wiggins, my traveling companion, has packed a bag of supplies, including a rusty pocketknife and a first-aid kit with bandages, antiseptic, and something called Dr. Seltzer’s Hangover Remedy. He has just dashed up to his room to add some Lomotil to his kit after spotting a suspicious substance floating in his breakfast Pepsi. He does not have anything that will raise the dead. But that has already been taken care of.

Zombies, according to my Webster’s are, “will-less and speechless humans in the West Indies… who are held to have died and been reanimated.” They are “people whose decrease has been duly recorded, and whose burial has been witnessed, but who are found a few years later living with a bokor (voodoo sorcerer) in a state verging on idiocy,” reports Alfred Metraux’s classic 1959 study, Voodoo in Haiti. You know about zombies if you ever saw Night of the Living Dead or a hundred other horror films. Wiggins and I had ourselves prepared for our Haitian expedition by renting and studying on my VCR a 1964 zombie film, I Eat Your Skin, in which the hero lands on “Voodoo Island” and remarks to a native, “I’ve heard a rumor that there’s an army of walking dead on this island. Is there any truth to that?” Minutes later, the hero and his friends are being chased by a mob of zombies (played by black people made up with what appears to be facial mudpacks over bad cases of acne). Those who are caught are themselves turned into zombies.

This prompted some discussion among those viewing the film with us as to whether Wiggins was in any danger of returning from Haiti as a zombie. His sister-in-law rightly pointed out that it would be very good for the story if he did and would also provide his wife with material for a sequel: I Was Married to a Zombie.

No soap, said Mrs. W. As far as she was concerned, zombification nullified wedding vows. Everybody laughed.

A few days later, we would learn that this is exactly what had happened in the case of Clairvius Narcisse.

WE’D FIRST HEARD of Narcisse, currently the most famous zombie in Haiti, through the work of E. Wade Davis, a Harvard graduate student in ethnobotany, a field that combines botany and anthropology. In 1983, Davis published an article in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology reporting on research he had conducted among Haitian zombies and zombie-makers. Following up on work done by a Haitian psychiatrist named Lamarque Douyon, Davis had concluded that there is “an ethnopharmacological basis to the zombi phenomenon.”

For centuries, followers of the voodoo religion, which is derived from West African religions carried to Haiti by slaves, have believed that zombies are real. Metraux reported cases of concerned relatives strangling or shooting the corpses of loved ones before burial, to prevent their being called back as zombies. A number of writers on Haiti reported the belief that zombies had never really died, but had been given a poison that only made them appear dead. This belief was reflected in the old Haitian Penal Code, which classified as attempted murder “the use that may be made against a person of substances which, without causing death, produce a prolonged lethargic effect… If following the state of lethargy the person has been buried, the act will be considered murder.” Nevertheless, most non-voodooists generally dismissed zombies as creature of folklore, existing only in the fevered imaginations of a superstitious people. Then Davis found the zombie poison.

Davis obtained samples of the poison from several bokors in scattered villages. The ingredients were not always the same— “It’s not like Merck Pharmaceuticals,” Davis told me later. “The potion varies.” But a handful of ingredients appeared again and again. These included human remains (chemically inert) and a large toad (Bufo marinus), parts of which have been used in Central and South America as a hallucinogen and an arrow poison. Most significantly, Davis found that the potions included several varieties of puffer fish. The skin and certain internal organs of these fish contain a lethal nerve toxin called tetrodotoxin, which, in minute doses, can induce severe paralysis and lower a person’s heartbeat and respiration to such a point that even a trained physician might mistakenly pronounce the victim dead. Such cases are well known in Japan, where the puffer fish, known as fugu, is consumed as a delicacy. Hundreds of Japanese gourmets have died from eating improperly prepared fugu, and the medical literature also records cases of “dead” fugu victims coming back to life as their bodies were being carted off to the crematorium.

The making of a zombie, Davis reported, involves religious beliefs and rituals. Even the bokors who administer the poison, he noted, truly believe that the poison kills and that it is skillfully practiced magic that calls a zombie back from the dead (except in the odd case where the poison kills “too completely,” or the victim suffocates in the grave). But it is the poison, Davis concluded, that makes zombification possible. A bokor administers the poison to a victim by applying it repeatedly to the victim’s skin or into an open wound or sore. The victim gets sick, “dies,” and though still conscious, is buried. The bokor goes to the graveyard at night, digs up the victim, feeds him an energizing counteragent (cane syrup mixed with sweet potato and a hallucinogenic plant called the zombie cucumber), and leads him away into slavery. Voila—one zombie, to go.

All of this was intriguing, so last summer I visited Harvard to call on Davis, but I was told he was back in Haiti. No one knew when he would return or where he could be reached. Professor Richard Schultes, Davis’s adviser and a pioneer ethnobotanist, showed me the last letter he had received from his student several weeks before.

“My field assistant and I have completely infiltrated the secret society,” it read. “We have been given the secret passwords, the ritualistic handshakes and forms of address, and the magic formulae of the poisons. I have entered into the initial phases of the initiation as it seems the only way to obtain the information I must have. The next phase is called the ‘nuit du,‘ the hard night, and it includes a blood oath and the consumption of a toxic preparation. At that time they are said to teach you what will happen if the secrets are betrayed. No one knows what this rite will entail as no white has ever gone through it, nor any anthropologist. The society Emperor has told me to bring two sets of clothes, for according to him the set one arrives in will be in rags by the end of the night. I am most anxious to obtain the ingredients of the toxic preparation.”

I finally tracked down Davis in Virginia several months later, where he had gone to recover from malaria and hepatitis (his dysentery had passed) and to write a book about his experiences. “I got so sick I didn’t complete the initiation,” he said. Still, he was confident he had learned the truth about the zombie poison and the zombification process. “The key to this kind of fieldwork is finding the secret that will get you the respect of the people you’re dealing with. In a lot of situations, in Haiti especially, it’s important not to appear to be afraid.”

Davis told me how he had obtained his first sample of the zombie poison from a bokor named Marcel Pierre. Pierre had given Davis a potion that Davis knew to be bogus. The next day Davis stormed into Pierre’s house, said he had used the poison on an enemy to no effect, and threatened to denounce Pierre as a fraud. Pierre produced a vial of the actual poison, which Davis pretended to rub on his hands. “The blanc is going to die,” Pierre told Davis’s assistant. Davis did not die; Pierre was impressed. Davis returned the next morning to find the proper ingredients for the zombie poison drying on Pierre’s clothesline.

Davis’s anger, his threat, his game with the deadly poison were all “part of the dance,” he explained to me. “That was just a dance that that particular culture demanded.”

IF WE HAVE to dance with zombie-makers, I resolve as we set out on our journey, I will let Wiggins lead. He has the pocket knife, and it is my obligation, after all, to return to tell the tale. We drive down the hill from the Hotel Oloffson into the crowded heart of Port-au-Prince—four of us in a little green Italian jeep. The driver, Jean-Claude, and the car have been provided by Dr. Douyon. Jean-Claude speaks French and Creole, the Haitian patois, but not English, so we have hired a translator from among the guides hanging out on the hotel driveway. He is Melfort, an eager young man wearing overlong plaid bell-bottom pants. He is looking forward to meeting the zombies, whom he has already seen on Haitian television.

We drive through streets jammed with pedestrians and honking communal taxis and minibuses, finally, out of the city into a countryside of villages of pink and yellow stucco huts surrounded by fields of sugar cane and banana trees. The terrain switches abruptly to desert, complete with cactus, and then back to lush villages again. To our right rise steep, dry mountains. To our left we can see the blue and turquoise Gulf of Gonave. As we drive, Jean-Claude listens to the results of the national lottery on the radio. His number does not come up.

We pass more villages, each with its cemetery, where elaborate tombs, like little houses, have been built above the graves by families who can afford them. We pass more patches of desert and signs marking dirt roads that lead down to the shore and the Jolly Beach Club and the Haitian Club Med. Melfort points out the road leading to the beach house of Haiti’s President-for-Life, Jeane Claude (“Baby Doc”) Duvalier. After 90 minutes, we arrive at the town of St. Marc. Across from an Esso station, we find the home of Marcel Pierre, the bokor who knows the secrets of making zombies.

THERE ARE TWO types of spiritual intermediaries in the voodoo religion, houngans and bokors. Houngans (priests) are the prime clergy. The preside over traditional ceremonies, intercede between individuals and the many voodoo gods, heal the sick, see the future, and dispense personal and political advice. Houngans know magic, but reputable houngans practice it only for good ends. Bokors (sorcerers) are not so scrupulous, dealing with the less savory voodoo gods. They are said to be priests “working with both hands.” Marcel Pierre, according to his reputation, has worked hard with the wrong hand.

A 1981 BBC documentary on the zombie phenomenon identified Pierre as a fomer member of the Tontons Macoutes, a dreaded secret police of the former president-for-life, Francois Duvalier. Moreover, the BBC said, Pierre is adept at making poisons and has admitted using them to kill people for money.

Davis holds the toxic puffer fish, which, when eaten, can induce a trancelike state. (Courtesy of Wade Davis)

“The BBC told me that Marcel Pierre is the incarnation of evil,” Davis had told me in Virginia, “and he simply isn’t. He’s not exactly benign… He went too far in the Tonton.” But, Davis said, Pierre had become his friend.

“Besides,” Davis asked, “if this guy is really the incarnation of evil, why is he living right among everybody? What is his role in the community? And then you get into what the purpose of sorcery is in African culture. It’s despised at the same time that it’s tolerated and considered essential, because there’s some kind of cosmic balance in the universe.”

THE SORCERER IS AT HOME when we call. A stern-faced man with inexpressive flat features, he leads our group into a cool, dark back bedroom, where he sits on a chair and asks us our business. He removes his dark glasses, revealing hooded eyes. He is wearing a yellow cap printed with the slogan, WILD WONDERFUL WEST VIRGINIA.

“I’d like to know if we can ask him a few questions,” I say to Melfort, who translates.

What do you want to ask about? he says.

I say we are en route to visit two zombies and are curious to know how and why zombies are made.

Narcisse is in Lestere, Pierre says.

“We know,” I say “That’s where we’re going.”

Pierre says he will lead us to the zombies, if we pay him. Melfort replies that we are just on a tour of the countryside today, and will return and see him tomorrow. I catch the drift of things and say thank you, we must be going.

Pierre follows us to the door.

You must walk with money to see the zombie, he says.

“Goodbye,” I say. “Nice to meet you.”

We are all in the car. Pierre leans in the window. When will you come back? he asks. Tomorrow afternoon, says Melfort. Jean-Claude puts the Jeep into gear and, without consulting me, turns south, back toward Port-au-Prince, away from our destination. He and Melfort are both shaken by their meeting with Pierre, and Wiggins and I don’t feel too great about the guy either. “He’s a very bad priestman,” says Melfort. “I don’t like his face. I don’t like to shake his hand. I don’t shake it when we left.”

We are still driving south, in the wrong direction. “We don’t want trouble with him,” Melfort explains. After a few minutes, Jean-Claude pulls off the road and turns back north. There is only one road, so we have to pass Pierre’s house. He is standing out front as we drive by. We see him and he sees us. Jean-Claude pulls off the road again and hesitates. Then he resumes driving north. We are all sweating in the car. Wiggins reaches into his pack of supplies and pulls out a canteen of New York City tap water.

We drive in silence until we reach the village of Lestere. Jean-Claude asks a man for directions, and he climbs in the car to show us the way. A hundred yards down a dirt road, a couple of turns, and we arrive at the edge of a hard, dusty clearing surrounded by small huts with corrugated-iron roofs. An old man wearing checked pants and, despite the heat, a long-sleeved rugby shirt, spots us and walks in our direction. Jean-Claude points to him and turns to me. “Zombie!” he says.

THE DOCUMENTATION of the zombification of Clairvius Narcisse was accomplished by Dr. Lamarque Douyon, one of Haiti’s leading (and only) psychiatrists. The trial that led Douyon to Narcisse began in 1957, when Douyon was studying psychiatry in Montreal. He was working with a doctor giving experimental drugs to schizophrenics and observing their behavior afterward. “They were just like marionettes,” recalls Douyon. “They had no initiative. They did whatever you told them to do. They were behaving like… zombies.”

Douyon concluded that the drugs could induce zombie-like behavior, and this intrigued him. During his next vacation in Haiti, he gathered a number of zombie cucumber (the hallucinogenic plant that has since turned out not to be the zombie poison but its counteragent) and took them back to Montreal with him. There he injected male mice with an extract from the plant. The mice became very passive for a couple of hours and then began to move normally again. After that, Douyon says, “I continued to interest myself in the zombie question.”

The day before our trip, Wiggins and I had found Douyon at his clinic in Port-au-Prince, next door to a line of people waiting to apply for visas at the American consulate. There was a crowd as well in Douyon’s waiting room. More than a dozen patients sat quietly, holding pieces of paper with numbers printed on them. “Dix-huit,” the nurse called shortly after Wiggins and I arrived. The patient holding number 18 got up and went into the doctor’s office.

While we waited, I browsed through the magazines on a waiting-room table and picked up a back issue of L’Assaut, the official organ of Jean-Claudisme, which is the political movement of President-for-Life Jean-Claude Duvalier (and to which the American analogy would thus be Ronaldism). I was reading about how a recent visit by some black American businessmen “constituted a new victory for the politics of opening initiated and led by the President-for-Life of the republic” when Wiggins and I were called.

Douyon’s office was equipped with a psychiatric couch and a noisy air conditioner. The doctor sat behind his deask in a white medical coat and told us, in not quote perfect English with a French-Haitian accent, how he had pursued his interest in zombies after returning to Haiti.

“I was looking for the zombies,” he said. “I was traveling all over the country looking for a zombie. Everybody in Haiti was convinced that the zombie was a real thing. I met some priests, Protestant pastors, and a lot of tea teachers, and many of the affirmed that the zombie was something real, and they even had pupils or friends who were zombies. They meant there were people who died; they had been to the funeral of those people, and after a few years those people came back and lived in the community… Somebody would tell me that in this part of the country you would find a zombie, so I would travel over there and ask everybody. But myself I wasn’t able to see a zombie.”

Finally, in 1979, the Haitian press reported that a zombie had appeared near Gonaives. Douyon was off again. He met and interviewed Narcisse and his relatives. He went to the well-known Albert Schweitzer Hospital near Deschapelles and found a death certificate, signed by two doctors (one Haitian and one American), showing that Clairvius Narcisse had died there in 1962. He talked to people who had been at Narcisse’s funeral. He brought Narcisse to a private hospital he runs in Port-au-Prince and treated him for a year. “When he was in better condition,” Douyon said, “I took him back to Lestere, and he is still living there, with his sisters, and they all accept him and share their family life very well.”

Douyon was interrupted by a shouting from the waiting room and a knock at the door. He went out. When he returned I asked him about the crowd of patients outside. “They are psychotics,” he said.

I said they seemed awfully calm for psychotics.

“They are on drugs,” he explained, “except for the one who just arrived.”

On our way out a few minutes later, we saw that one. He was sitting, quietly now, in a chair in the waiting room. A chain was wrapped around his wrists and padlocked. Douyon turned to us with an embarrassed laugh. “They should not have done this,” he said.

Voodoo believers, when possessed, eat fire without harm. (Photo: Wade Davis)

IN THE NARCISSE FAMILY compound, we are greeted by an uproar. In a matter of seconds, a dozen people crowd around us, and one of Narcisse’s sisters, barefoot in a white dress with a toddler clutching her leg, begins screaming at Jean-Claude. He has told her that we are from Dr. Douyon. How is she supposed to know that, she shouts. How does she know we are who we say we are?

While she shouts, a neatly dressed old man appears with some wooden chairs and quietly sets them out beneath the shade of a tree in the center of the compound. He seems to know how the argument will end. The first person seated is Gracelle, another sister of Narcisse. When her sister stops for breath, Gracelle takes the argument in a new direction.

The family has incurred certain expenses caring for Narcisse, she says. She knows that interviews with Narcisse are worth a great deal of money to the movies in Canada and the United States. Narcisse is incapable of dealing with money, so we should deal directly with her. If we giver her $100, we can talk to Narcisse.

“Twenty dollars,” I say.

Out of the question, she snorts. How about $70?

I say okay.

Narcisse has been wandering around distractedly during all of this. Now he reappears in clean clothes —white pants, a blue striped shirt, and tennis shoes. He sits opposite us beneath the tree and, with all his relatives gathered around, begins to tell the story of his death.

Melfort translates:

“He get sick Sunday, and Tuesday they take him to the hospital. He gave a blow-up. He give blood.” (Narcisse gestures to show the blood gave forth out of his mouth.) “He is dead on Wednesday. When he is dead, he can hear his sisters cry, but he cannot talk.”

Well then, was he dead or wasn’t he dead?

“He thinks he is dead. Then he know he is dead because they put him in the coffin and in the ground. He know he is finished. He know he is gone forever.”

Narcisse leans forward in his chair. He has a high-domed bald head and sparse white whiskers on his face. He points to a scar at the corner of his mouth. It was made, he says, by a coffin nail. The man pounding the coffin shut drove a nail right into his face. “He is too big for the coffin,” Melfort explains.

While we listen, two goats are butting heads behind one of the huts. A gust of wind comes up and blows sand in our faces. Narcisse shields his eyes, which are yellow.

He was buried on the Wednesday he died, he continues, and he lay in his coffin until Saturday night, all the while breathing through his armpit. “When you zombie, you breathe there,” Melfort explains. Then the bokor and his assistants arrived at the graveyard. “They make a ceremony and invite the zombie to come. The top of the coffin fly away. The land opens. They tell the zombie to stand up. He stands up. They slap him in the face. They tie him with rope.”

Had he been poisoned? I ask.

No, says Narcisse, there was no poison. He died because an enemy put a watermelon in the ground and stuck it with a knife. This accounts for the pain in his chest and the red blood he spit up during his fatal illness.

A little naked boy from the waist down is standing next to Narcisse. Narcisse pauses, draws a little handkerchief out of his pocket, and wipes the child’s dirty nose. Then he continues:

After being summoned being summoned from the grave, he was led away to the farm of a bokor near Pilate. There he did agricultural work with 150 other zombies until, after two and a half years, a newly arrived zombie rose up and killed the bokor. Then Naricisse wandered off and continued to wander until the day in 1980 when he returned to Lestere and confronted his sisters in the marketplace, causing such a commotion that the local police locked him up for his own protection.

Why had he stayed and worked for the bokor?

Because the bokor had taken his bon-ange, of course. (The bon-ange or ti-bon-ange is, according to voodoo, the part of the human soul that animates the personality of the individual.) “If the bokor not take his bon-ange,” Melfort says, “he would have sense and know where he are and would leave. But he no have his bon-ange. He cannot wake up his head.” He recovered his bon-ange after running away, Narcisse says, by eating salt, which, it is well known, restores the bon-ange to a zombie.

Everybody is listening to this tale, except for a few of Narcisse’s relatives, who have heard it many times before and begin to wander off. We move to leave as well, with Narcisse, who will accompany us on the rest of our trip.

As we walk towards the car, Gracelle calls after us, “Don’t forget to see his grave!”

We do not. A few miles down the road, we stop at an old village cemetery. Narcisse walks directly to a waist-high tomb and sits. He looks to one side, to where a heavy concrete slab is set in the ground. Written on the slab are the words, ICI REPOS CLAIRVIUS NARCISSE 3/5/62.

Narcisse says something to Melfort, and Melfort translates.

“He says he is in good shape now, but not as good as before he is dead.”

LATER IN THE DAY, Narcisse tells us more about the circumstances behind his death. It was engineered, he says, by his late brothers, who were lazy and good-for-nothing envied his industriousness. This differs a bit from the story Narcisse has told others—that his brothers and he were feuding about some land.

Both versions of the story were denounced by and expert we consulted later. “I could not imagine that someone would lie even beyond the tomb,” said Max Beauvoir, “but Clairvius Narcisse did.”

Beauvoir is a houngan who was trained as a biochemist at Cornell and the Sorbonne before returning to Haiti and taking up the priestly post he inherited from his grandfather. He presides over an attractively designed voodoo temple a few miles south of Port-au-Prince, where, every night, tourists are invited to view authentic voodoo ceremonies for $10. (Wiggins and I had attended one, during which a celebrant had bitten the head off a chicken and then been possessed by Agway, the voodoo god of the sea. Other celebrants put live coals in their mouths. “I’m impressed,” Wiggins had told Beauvoir, “and I’m from New York.”)

Zombies are not created randomly or as the result of petty feuds, said Beauvoir, who was an important consultant to the research of Wade Davis. Bokors are the leaders of secret societies, he said. One role of the societies is to uphold traditional law, and zombification is a sort of capital punishment for those who violate that law. “Those who make zombies,” Beauvoir said, “are the equivalent of executioners.”

In 1962, Clairvius Narcisse wanted to sell his share of a piece of land he and his siblings had jointly inherited from their father, Beauvoir said. Under official Haitian law, Narcisse had the right to do that. But it was a violation of traditional law, because it would have displaced some members of his family who lived off that land. Nevertheless, Beauvoir said, “Narcisse insisted. He was physically taken into the secret society. He was tried by his peers. He was given people to defend him. He was asked to change his mind. He still insisted, so he was made into a zombie.

(Every documented zombification has a similar story, Beauvoir said, and Wade Davis told me later that his research supported this conclusion. “There’s some random making of zombies, too,” Davis said. “But I believe that zombification is a form of social sanction…I know that Narcisse was judged.”)

Beauvoir confirmed, however, another poart of Narcisses’s story, that the means of his zombification was the removal of his ti-bon-ange by spiritual means. Poison is irrelevant to the making of a zombie, Beauvoir said. Some zombie makers use it “for support,” to buck up faith in their magic. “But zombification is purely a spiritual matter. One part of the soul, the ti-bon-ange, is removed using techniques that are well known.” He often removed the ti-bon-ange himself, Beauvoir said, in the course of preparing people for spiritual instruction. (But he always returned them afterward, he added.)

When the proper ritual is employed, Beauvor said, zombies can be created at a distance, with no direct contact between the bokor and the victim. Moreover, he said, a new trend in the field is to retrieve zombies from their graves at a distance as well. Only “small bokors of bad repute” bother to go digging up graveyards nowadays, Beauvoir said. “The best people will tell you they no longer raise zombies in cemeteries. You stay at home and command the zombies to come to you.”

DRIVING NORTH from Narcisse’s empty grave, listening to him (allegedly) lie from beyond the tomb, Wiggins signals that he is getting uncomfortable in the back seat. It is very hot, the back windows don’t open, and Wiggins is crammed in between one perspiring translator and a zombie. Meanwhile, I am getting hungry. It is time to take the zombie to lunch.

We stop in Gonaives and find and air-conditioned restaurant. The cool air bothers Narcisse; he prefers the heat, he says. But otherwise he has really loosened up. With his sisters, he was quiet and withdrawn. Now he is starting to have fun, spellbinding one and all with amazing tales of zombie life.

If anyone stole anything from the fields where he worked as a zombie, Narcisse tells us, the zombies would kill the thief. Narcisse killed one or two himself, he says. The waiter laughs. Narcisse orders Coca-Cola and grilled chicken.

When zombies get old, Narcisse tells us, they are turned into cows. Jean-Claude yelps and slaps the table in amazement. It’s true, says Narcisse. One Christmas Eve the bokor went off with a zombie and returned with a cow, which was cooked and served for dinner. In the morning the bokor told Narcisse and his fellow zombies, “You ate your brother last night.”

I have a question: Who was the little naked boy whose nose Narcisse so solicitously wiped back at the family compound?

His son, Narcisse says.

Now I am surprised. Narcisse is about 70 years old (he guesses), and he looks it. Moreover, he’s had a hard life. The little boy was about two. Narcisse sees my surprise and laughs.

“Yes,” Melfort repeats, “he makes babies. And the little on is not the last one. When he come back, his first wife doesn’t want him anymore. She say she’s not going to live together with a zombie. Now he has a young wife. He’ll show you his young wife.”

The waiter brings our food, and he has a question: “Did the father of the church accept to baptize the child?”

Narcisse says he’s not Catholic but Baptist, and the Baptist minister had no problem about baptizing a zombie’s children.

Narcisse eats heartily, carefully piling his cleaned chicken bones on Melfort’s salad plate. After lunch we drive off again toward a Baptist missionary compound in the village of Passe Reine. This is the home of Francina Illeus, the first zombie found by Dr. Douyon.

When we arrive, a crowd of young women and children is standing in the shade of a mango tree, enjoying some late afternoon conversation. The women know Narcisse. When they see him, they start to tease him good-naturedly. Is he married? Why doesn’t he marry to-Femme (Francina’s nickname)? Two zombies belong together.

“Ti-Femme!” the women shout at a pretty young woman at the edge of the crowd. Someone tells her to clean up. She ducks into a building and emerges a few minutes later in a clean flowered dress. Children have set out chairs beneath the mango tree and ti-Femme sits. But she will not talk to us.

A man in a Pizza Hut shirt tells her we come to take her to Dr. Douyon. She turns her head away and whispers, “Non. Non. Non.” She looks very unhappy. Melfort says we will pay her to talk to us. I catch her looking at me. She quickly turns away again. She whispers, “Non…non.“

Up to a point, Francina did what she was told. She washed, she dressed, she sat. But she will say nothing. She is not playing in our ballpark. She seems a million miles away, like a semi-catatonic, like a, yes, zombie.

On the road back to Lestere, everyone agrees that it is too bad about ti-Femme. The bokor still has her soul, Melfort says. Narcisse speaks and Melfort translates. “He says he is very lucky to come back and not be silly.

Then Narcisse tells us he is planning to visit Canada soon.

Will he take his young wife? I ask.

“No,” Melfort says, and he laughs. “Maybe he find another woman there, if she don’t know he is a zombie.”

Edward Zuckerman is the author of The Day After World War III.