Who makes history? Who writes it, and who features in it? For Women’s History Month this year, Oprah Daily wants to honor women who have played roles outside the spotlight: grandmothers, resistance workers, and professors. We also are taking another look at figures we thought we knew, including the familiar faces of the Black Madonnas of France. One of the essays in this collection quotes Virginia Woolf, who said, “We look back through our mothers if we are women.” Look back with us at the remarkable women who made our history.

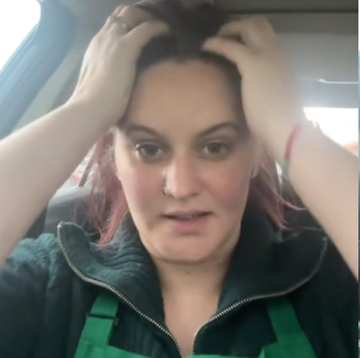

When I walked to Vichy, France, to visit its 12th-century Black Madonna, whom I lovingly nicknamed She Who Cherishes Our Hot Mess, I sublimely stood before a sacred walnut wood statue of a holy woman who looked like She could be my mother. Though I was alone in a cavernous, dimly lit church, I instinctively knew I was safe in the presence of the Black Madonna of Vichy, who is especially known for welcoming the needy. As I spoke to Her of the internalized shame I carried as a Black woman, I joined a powerful, centuries-long lineage of peasants, African migrants, abused women, and neglected children who traveled by foot across the Auvergne’s Chaîne des Puys volcanic mountain range to speak to Her of their need. Her Black and female body assured me that She cherished my Black and female need as I laid it on Her altar.

But my journey didn’t start in France. As a child in Sunday school, I learned that questioning the goodness of a God who murdered the entire world in a flood would not be tolerated. At home, I learned that asking why Dad was the head of everyone, including Mom, was a punishable offense. As a young adult, I received death threats when I published an article questioning why, despite its historical inaccuracy, we rarely challenge the image of a white Jesus. So I buried my questions deep under the soil of my soul, promising to return to them when it felt safe. There were deeper questions:

Why does white patriarchy get to create God in its own image?

If God is white and male, then how can a Black woman like me ever be truly sacred?

Are there any spiritual icons that unapologetically affirm my Blackness and femaleness?

But as the time passed, I never asked them. To be certain, my experiences invariably led me to more progressive beliefs and action. For example, my experience as an unmarried Black woman led me to reject the conservative gender roles my parents handed down to me and adopt more liberal ones within my faith tradition. In this way, I was able to create enough wiggle room to work within the patriarchal religious system. Indeed, I found meaning and joy in my faith-based justice efforts as I advocated for women, for people of color, and for myself. But as the time passed and I moved on to my 30s, I never felt fully free, and the deeper questions remained untouched.

The moment I met Her, everything changed. It was in the wake of Donald Trump’s 2016 election, and I was desperate for a divine being that spoke directly to the pain I carried as a Black person and a woman. I was vaguely aware of the Black Madonna, an uncommon dark-skinned version of the Virgin Mary, so I ordered a slew of books on the little-known Catholic figure. To retrieve the shipment, I had just braved a rainy gauntlet between my porch and the cavernous mailbox at the end of my long gravel driveway and was drying off with a cup of cinnamon cardamom tea in the nest of blankets on my kitchen couch. Before studying the text, I casually flipped to the illustrations of the uncommon dark-skinned version of the Virgin Mary within. Before I even read anything, my soul immediately recognized that these photos and drawings of ancient Black Madonnas affirmed my questions about the Divine—questions that first surfaced when I was a young girl and were quickly buried. I learned that there are over 450 Black Madonnas around the world, most of whom are over a thousand years old, with names as illustrious as Our Lady of the Good Death, Slave Mama, and Dear Dark One. Though they are often housed in Catholic churches, many are believed to be modern-day versions of the ancient dark goddesses, such as Isis, Demeter, Cybele, and Artemis. In fact, the Black Madonnas draw seekers of all religions and creeds and welcome all who need healing and empowerment.

The thousand-year-old Black Madonnas depicted in the books in front of me liberated my questions with the force of a cork popping off a thousand-year-old bottle of Champagne. The late bell hooks experienced a similar freedom when she encountered the Black Madonna. She later lamented, “Unfortunately, African Americans have not been interested in reclaiming representations of black Madonnas.… And this is a sensitive point, because most constructions of Black femaleness are tied to representations that are hateful and ugly, so the idea of an icon that can stand in resistance becomes further and further away.”[i]

The images of a loving and beautiful Black female God showed me that my questions are not only valid but are harmonious echoes of questions heard around the globe and across time. Over the following months, I devoured every book I could find on Her.

But my soul longed for more than book knowledge; I longed to gaze into Her mysterious and kind eyes, to witness Her unyielding clutch on Her precious Black boy, to run my fingers along Her centuries-old dark, wooden body, and to stand before a sacred image of Black femininity. So I embarked on a solo, physically demanding yet soul-soaring five-week walking pilgrimage across Auvergne, a mountainous region in central France. There, I walked over 400 miles to visit 18 Black Madonnas in remote village churches. During my pilgrimage, I powerfully experienced that the Black Madonna represents a loving and beautiful Black female divine that can absolutely stand in resistance to all the ways that the white patriarchal world had denigrated me.

During the French Revolution, insurgents stole and decapitated the Black Madonna of Vichy. However, the oppressed people who loved Her tracked Her head down, built Her a new walnut body, and pieced Her back together. When I visited Her on my pilgrimage, I knew I could tell Her that as a Black woman living in a white patriarchal world, I had been decapitated, too. I knew I could tell Her that even after years of trauma therapy and mindfulness meditation, it still often feels like my body, emotions, and heart are miles away from my overdeveloped, overeducated, over-linear brain. I knew She understood because She, too, had been severed and She understood that the process of being pieced back together is a sacred weaving that cannot be rushed. Her story of healing was proof to me that my healing does not have a deadline and that every step in any direction belongs. In She Who Cherishes Our Hot Mess, I encountered a God who unapologetically affirms my Blackness and my femaleness.

In Her company I also experienced unconditional acceptance, what Clarissa Pinkola Estés described when she wrote, “The Black Madonna, in all her representations, is known as the healer of crippledness, the healer of harmed women, hurt men, and injured and abused children.… She is mother mild and tender, mother most alert and tending to, mother most fierce and protective, and mother who heals the worst of the wounded.”[ii]

Though bell hooks has joined the ancestors, it’s not too late to follow her guidance as Black women and reclaim Black Madonnas. If we look to the Black Madonna, She will show us how She’s always been right here welcoming our need, showering us with love, and affirming the sacredness of our Black femaleness.

[i] bell hooks, Homegrown: Engaged Cultural Criticism (2006)

[ii] Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Untie the Strong Woman (2011), p. 145.

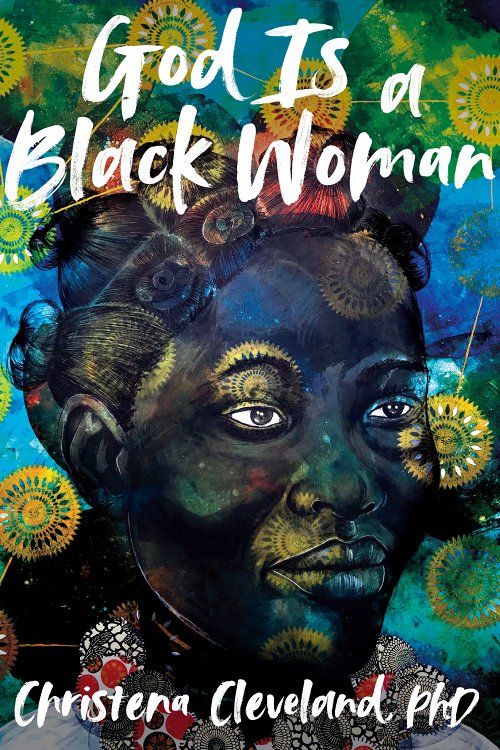

Christena Cleveland, PhD, is a social psychologist, public theologian, author, and activist. She is the founder and director of the Center for Justice + Renewal as well as its sister organization, Sacred Folk, which creates resources to stimulate people’s spiritual imaginations and support their journeys toward liberation. Her book God Is a Black Woman was published in 2022.