Venus is volcanically alive, stunning new find shows

The discovery may help scientists answer an existential question: What mysterious cataclysm turned Earth’s sister world into a fiery hellscape?

For half a century, scientists have dreamed of spying erupting volcanoes on Venus. This unfathomably hot world is obfuscated by noxious clouds, but past missions have revealed the surface is covered in volcanic features. And now, thanks to the recorded memories of a long-dead spacecraft, scientists have struck scientific gold: They’ve seen a vent on Venus change shape, expand, and appear to overflow with molten rock.

“My bet is there was an eruption of a lava lake,” says Robert Herrick, a planetary scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and one of the new study’s two co-authors.

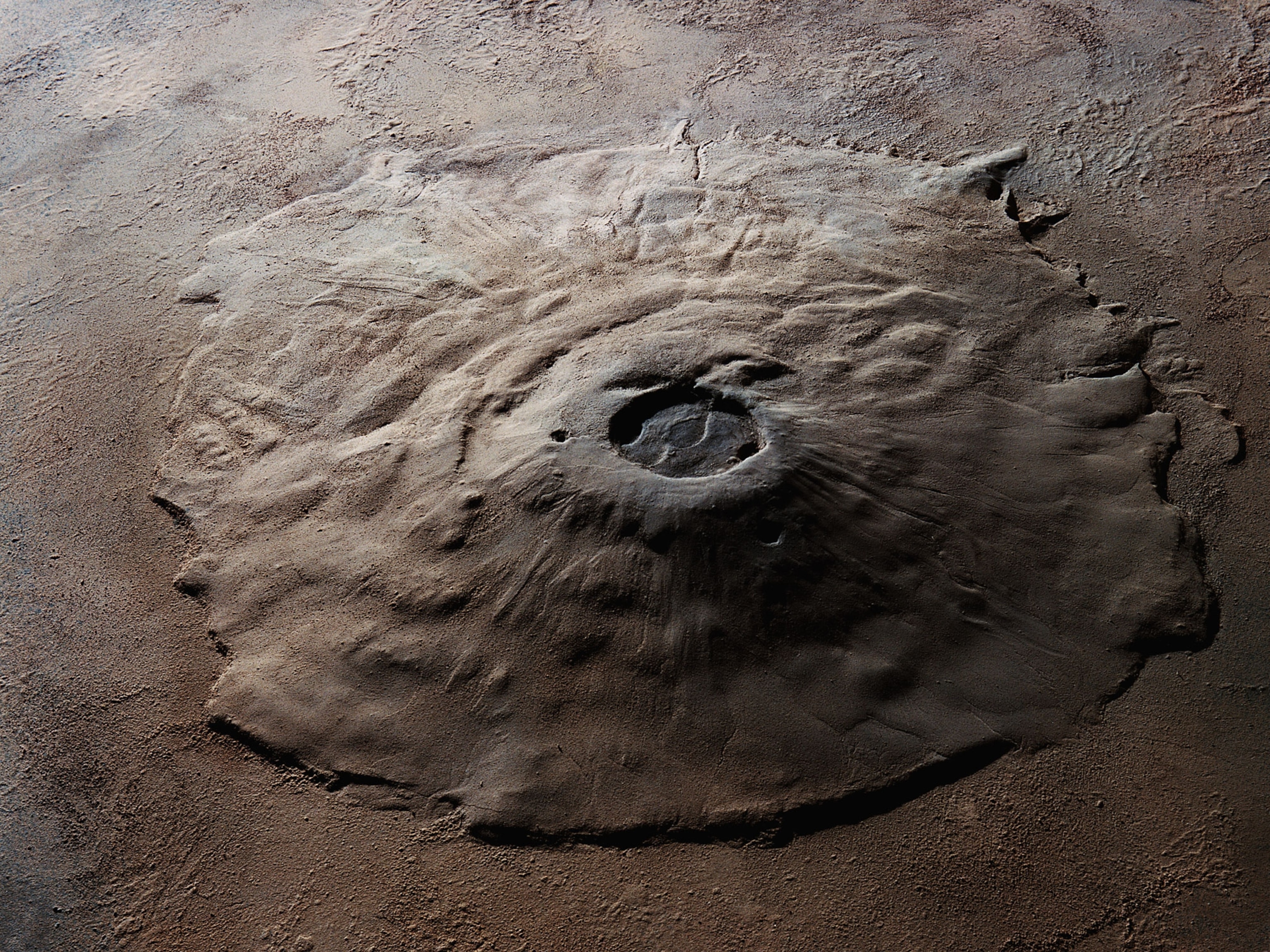

As reported today in the in the journal Science, Herrick and a colleague spotted the volcanic maw—on the side of the colossal volcano Maat Mons—in radar images taken by NASA’s Magellan spacecraft in 1991.

“This is one of the most convincing pieces of evidence we’ve seen,” says Stephen Kane, a planetary astrophysicist at the University of California, Riverside, who was not involved with the work.

The results have stunned the scientific community. Experts expected to find erupting volcanoes on Venus, but not until two spacecraft with cutting-edge, cloud-penetrating radar systems—NASA’s VERITAS and Europe’s EnVision—arrive sometime in the early 2030s.

Evidence of ongoing volcanic activity on Venus has existential implications. The planet is much like Earth in size and composition, but its considerable ancient stores of water—possibly in the form of oceans—were vaporized long ago when the planet was scorched during a mysterious cataclysm. Runaway climate change triggered by apocalyptic eruptions remains the prime suspect. By understanding Venus’s present-day volcanism, scientists can learn more about the divergent fates of Earth and its blistering sister world.

“If you want to understand the only other Earth-size world we will ever get to, anywhere in the universe, Venus is the only choice you have,” says Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis who was not part of the new study.

A hidden hellscape

Venus’s opaque atmosphere prevents its surface from being seen from Earth. Only a handful of spacecraft have perceived the landscape, either by plunging through the clouds and surviving for no more than an hour or two on the oppressively hot surface, or by orbiting the planet and peering through the clouds with technologies like radar.

A fleet of Soviet spacecraft revealed Venus to be almost entirely covered in volcanic structures—some Earth-like, others distinctly alien—back in the early 1980s. Hoping to map the planet’s features in unprecedented detail, NASA’s radar-equipped Magellan spacecraft arrived in 1990.

By repeatedly orbiting the planet and examining the same places several times, scientists hoped to spot signs of volcanic activity. But there were complications. The low resolution of the radar meant that any physical changes would have needed to be sufficiently big to show up on the images. And early in the mission, Magellan’s orbit began to deteriorate, causing the spacecraft to map less of the surface on each successive trip around the planet.

Despite these challenges, 43 percent of the planet was mapped at least twice. But comparing multiple images of the same volcano to look for changes also proved problematic, as the angle of each shot frequently differed between orbits.

In the decades following the mission, nobody managed to find a convulsing volcano.

A metamorphosing volcanic maw

Scientists have found plenty of indirect evidence for active volcanism on Venus, including spikes in atmospheric gases linked to volcanic belches, suspiciously youthful mineral patches, and unusual features on colossal circular structures named coronae that imply an underlying magmatic churn.

“We seem to keep getting teased by these indirect pieces of evidence,” Kane says. But the holy grail—a spewing volcano or a flowing river of molten rock—remained elusive.

In 2021 EnVision and VERITAS were selected for launch, thereby becoming the best bet at finding active volcanism on Venus. But Herrick remained impatient.

“I had lots of Zoom meetings where I didn’t need to be fully engaged,” he says, referring to the height of the pandemic. “Whenever I had an hour here or there, I just started looking” at the old Magellan data. He manually aligned images of Venus’s volcanoes, searching for anything odd.

During one search, Herrick forensically examined Maat Mons. Named after the Egyptian goddess of truth and justice, it is the tallest volcano on the planet—and on one of its flanks, between February and October 1991, something changed. In those eight months, matter appears to have flooded into an open vent, which grew from 0.8 to 1.5 square miles, and a fresh stream of material seemingly oozed downslope.

“I think this really is something,” Herrick recalls thinking. He ran it by his co-author, Scott Hensely of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who agreed: something volcanic had stirred.

The vent-filling substance could be rocky debris from a landslide. It is also possible that the stream-like feature was already present in the February imagery but could not be seen due to the angle of the images.

But the most probable scenario is that in 1991, a huge eruption of lava filled the expanding vent, and some of it poured over the rim or bled through a fissure. “We can definitely say it changed shape,” Herrick says. And when a volcano changes shape that dramatically on Earth, the root cause is always molten rock.

Searching for Venus’s heartbeat

After so much circumstantial evidence, “this is the first time we see a change in something,” says Anna Gülcher, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology who was not involved with the work.

“I think what they’ve seen is real,” Washington University’s Byrne says. He suspects that the vent’s alteration could have been due to subterranean movement, such as magma shifting violently below ground, rather than an eruption.

Scientists hope to answer a fundamental question: “What is the day-to-day volcanic heartbeat of the planet doing?” Byrne asks.

The volcanoes of Earth and Jupiter’s moon Io are always erupting. Mars might erupt once every few million years. Where does Venus fall on that spectrum?

The discovery suggests the planet has something closer to a vivacious, Earth-like volcanism. VERITAS and EnVision are set to answer this question, but until then, this study will encourage scientists to peruse Magellan’s records, hoping to find another erupting Venusian volcano.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

Environment

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- Why this unlikely UK destination should be on your radarWhy this unlikely UK destination should be on your radar

- A slow journey around the islands of southern VietnamA slow journey around the islands of southern Vietnam

- Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?

- 5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks

- Paid Content

5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks