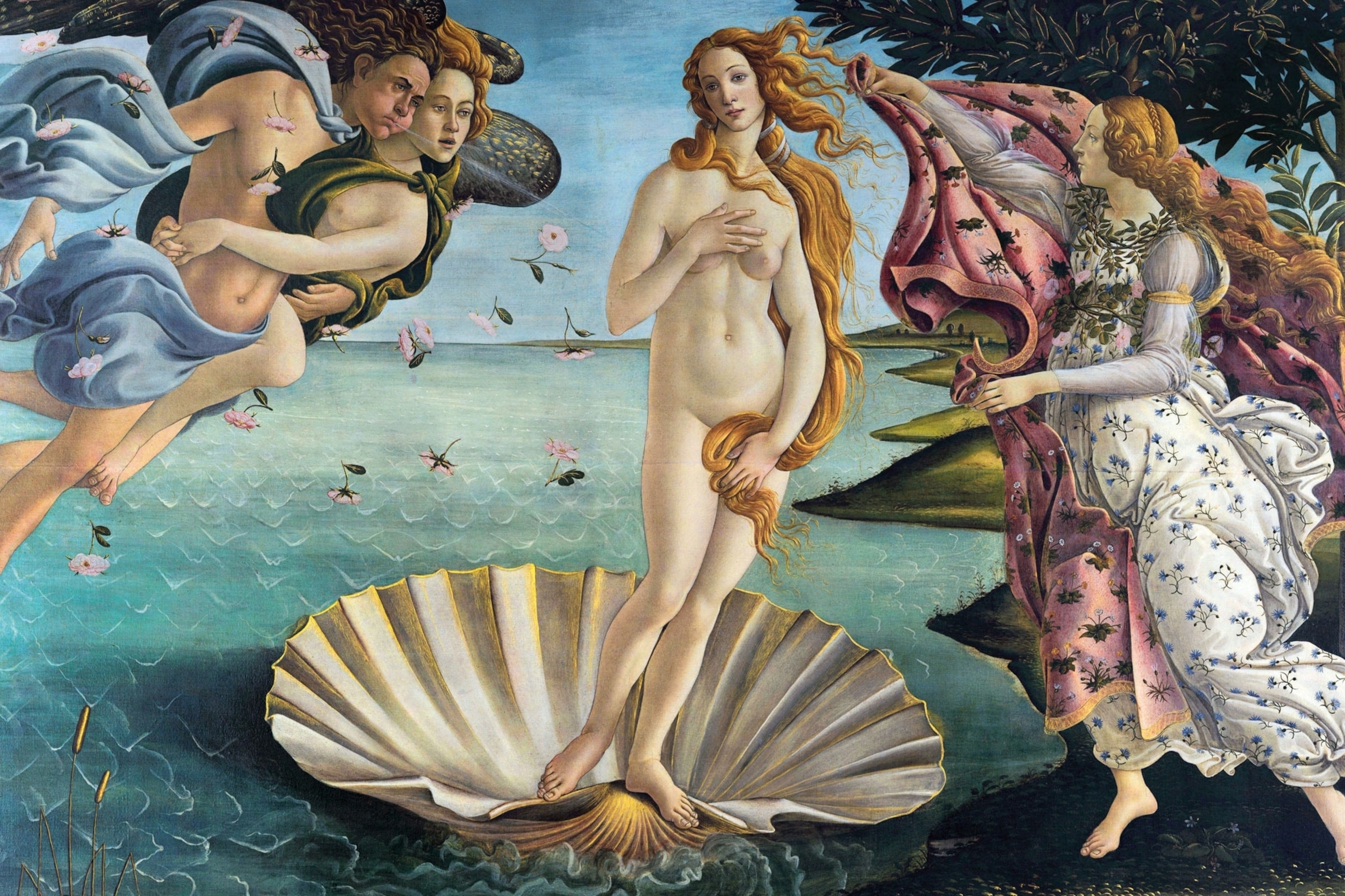

The painter behind 'Birth of Venus' invented a new kind of art

Breaking new ground, Botticelli's iconic Renaissance masterpieces used Christian themes and classic myths to celebrate his patrons, the Medici.

Christened Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi, Sandro Botticelli began life around 1445 as the youngest son of a tanner in Florence, was a small Italian city state. Devastated a century earlier by the Black Death, the city recovered and grew in prominence and prosperity. Powerful merchants and bankers invested their fortunes in painting, sculpture, and architecture, and Florence became the epicenter of a new movement that most eloquently expressed its values—humanism, wisdom, and truth—through the arts. The work of Sandro Botticelli embodied the values of the early Renaissance, marrying organic beauty with geometric precision.

Golden Boy

Sandro had an older brother, who was allegedly called “barrel” because of his stocky build, and it is thought that this is how the young Sandro got the nickname Botticelli. The name stuck with him for the rest of his life and became synonymous with some of Florence’s greatest works of art. (See also: The Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo's masterpiece.)

The details of the artist’s early life are few. Of Botticelli’s childhood, the 16th-century historian Giorgio Vasari wrote: “Although [Botticelli] found it easy to learn whatever he wished, nevertheless he was restless ... [and, so,] weary with the vagaries of his son’s brain, in despair his father apprenticed him as a goldsmith.” This experience emerges in Botticelli’s paintings in the form of meticulous, intricate flourishes.

During Botticelli’s youth, Florence was the center of innovation in Italian art. The Florentine sculptor Donatello used his extensive knowledge of classical works to push his art to new heights. The Dominican Basilica of Santa Maria Novella housed the “Holy Trinity” fresco by Masaccio. Completed in 1427, it is believed to be the first work to fully apply the laws of linear perspective. (See also: Finding Donatello's 'Lost' Masterpiece.)

Mayn scholars believe that the Vespuccis, wealthy acquaintances of Botticelli’s family, secured him an apprenticeship with Fra Filippo Lippi, one of the greatest painters in the region. Lippi had a workshop in the nearby town of Prato, and the teenage Botticelli studied with him and painted his first works under Lippi’s tutelage.

Florentine financiers

Renaissance artists such as Lippi and Botticelli relied on powerful patrons to fund their work. In 15th-century Florence, the powerful Medici family financed many of the era’s greatest artists. The Florentine branch of the family made its fortunes in textiles and banking. (See also: How table manners as we know them were a Renaissance invention.)

Cosimo de’Medici came to power in 1434 and immediately set about an extensive building program, including finishing Filippo Brunelleschi’s gravity-defying cupola on Florence’s duomo of Santa Maria del Fiore. All this new architecture created a demand for works of art to fill them, which artists were only too happy to supply. (See also: Brunnelleschi's Dome.)

In 1464, during Botticelli’s apprenticeship, Cosimo died and was succeeded by his son, Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici. Five years later, Piero’s sons, Giuliano and Lorenzo (later “Lorenzo the Magnificent”) became co-rulers and continued feeding the appetite for great art begun by their grandfather.

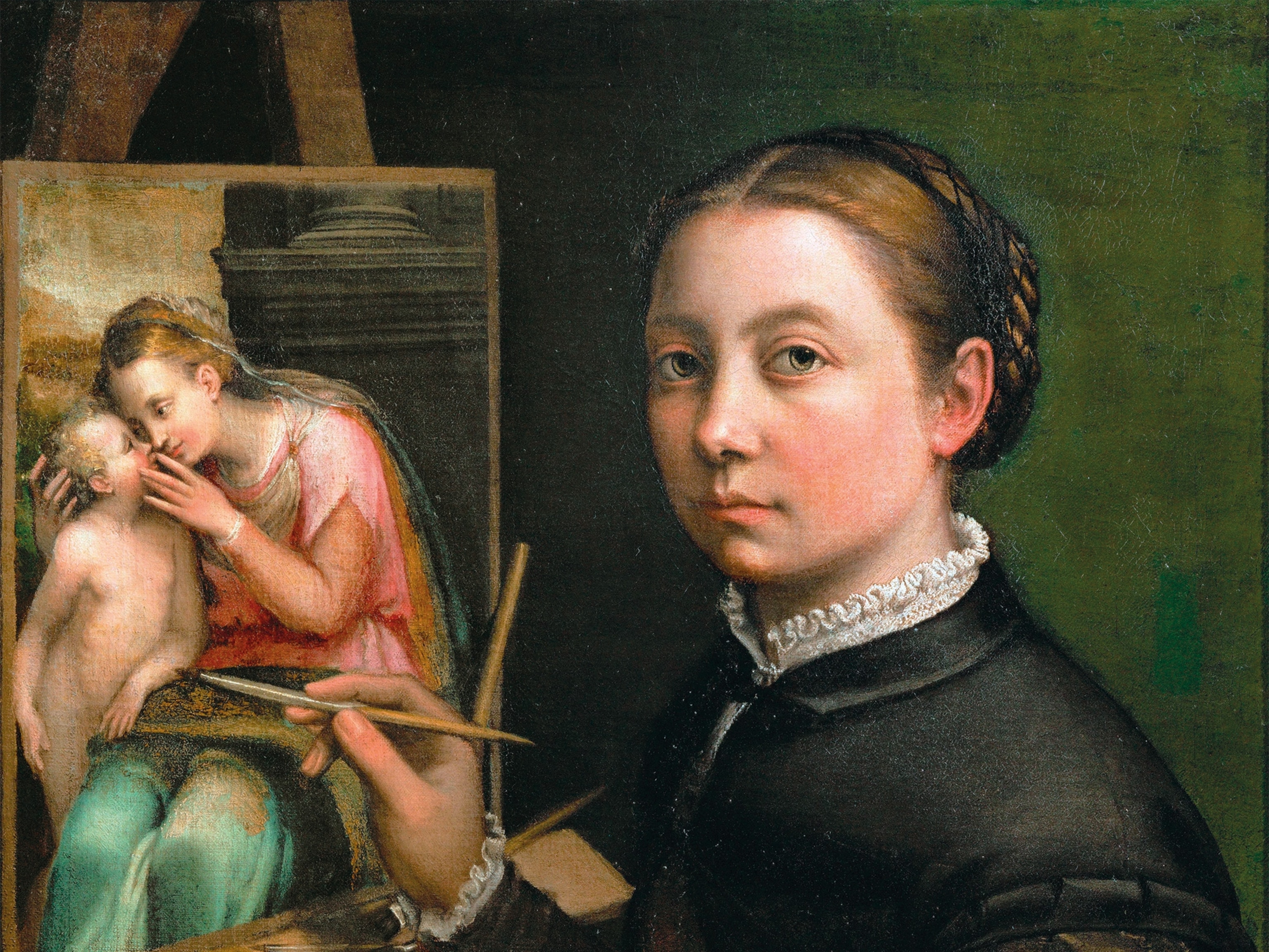

Around 1468, Botticelli left Lippi to study with other masters, including Andrea del Verrocchio, Leonardo da Vinci’s teacher, whose influence introduced a sculptural, solid quality to Botticelli’s figures. During the 1470s, Botticelli set up his own workshop. Although his patrons often selected his subjects—both sacred and secular—Botticelli embodied the Renaissance ideal of the individual artist, free to let his genius define his distinctive style. He proved a masterful painter of altarpieces and of circular, devotional paintings called tondi, the best known of which is the “Madonna of the Magnificat.”

During this time, Botticelli began a close working relationship with the Medici, who commissioned several paintings from him. These include “Portrait of a Young Man with a Medal of Cosimo the Elder,” from 1474-1475, and the 1475 “Adoration of the Magi,” which contains portraits of members of the Medici family paying tribute to the Holy Family. (See also: Who were the three kings in the Christmas story?)

Botticelli’s career coincided with the flourishing of Neoplatonism, a Renaissance philosophy based on the teachings of Plato. Neoplatonism acknowledged the supremacy of spirit over matter and viewed intellect and love as leading the soul toward God. Cosimo encouraged this philosophy, which was continued by his heirs. They also looked to the classical world to illustrate truths about their own.

Botticelli’s most famous works also draw on the classical world for inspiration. Commissioned by the Medici, his great mythological works of the 1480s—including “Primavera,” “Birth of Venus,” and “Pallas and the Centaur”— reflect Neoplatonist values in their beautiful renderings of classical material. At first glance, these works are entrancing on the surface, but Botticelli’s fluid brushwork and intricate details create new levels of meaning, both allegorical and symbolic, to engage the viewer.

Changing times, changing art

Botticelli’s religious works also earned him fame. He made a rare trip to Rome in 1481 to work on frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. Vasari’s account of the Rome visit is an interesting insight into how Botticelli lived generally: “Having rapidly squandered his earnings, he lived in haphazard fashion, as was his custom.”

In 1492, the political climate in Florence shifted after the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent. A Dominican friar, Girolamo Savonarola, gained influence in the wake of Lorenzo’s death and attracted many spiritual followers who opposed the Medici. According to Vasari, Botticelli fell under Savonarola’s sway, which led him to give up painting, his only means of earning a living. Vasari recorded: “Nonetheless, he remained an obstinate member of the sect.”

This master of the Italian Renaissance died in 1510, at age 64. Many of his most celebrated works were, by then, hung in the landmarks of his district, buildings he had known since childhood, including the Ognissanti Church, where he was laid to rest in a modest tomb.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavoursDina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavours

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?