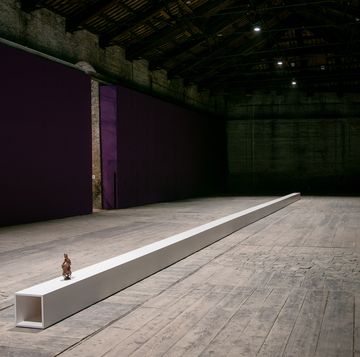

On Wednesday, May 15, 2019, Christie’s sold a Jeff Koons sculpture for 91.1 million dollars, the highest price ever paid for the work of a living artist. Purchasing the shiny stainless steel “Rabbit”, created by Koons in 1986, was Robert E. Mnuchin, an American art dealer and father to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin.

The record-setting purchase is just the latest sale to confirm Jeff Koons as an artist of sculptural trophies preferred by the ultra rich, after his Balloon Dog (Orange) sold for 58.4 million in 2013.

Oddly enough, the artistic career of Koons, more than a linear path to success, has followed a contradictory, controversial, and irregular trajectory: in 2017, a fall in demand for his more recent works combined with lower sale prices and various accusations of plagiary led to the downsizing of his studio (from 60 to 30 people).

“There are so many strange, disconcerting aspects to Jeff Koons, his art and his career that it is hard to quite know how to approach his first New York retrospective, the Whitney Museum of American Art’s largest survey devoted to a single artist.”, wrote Roberta Smith in the New York Times.

So, for a better idea, we take a closer look at the origins of the 64 year old American artist who first began at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore before graduating from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1976.

In 1977, the artist moved to New York, where he began work at the Museum of Modern Art, making a name for himself with his extravagant clothes and hair, not to mention his impressive ability to sell art. It was in this period that Koons began to work with the inflatable flowers and rabbits, using a combination of plastic, plexiglass, and mirrors to produce unexpected sculptures. Then, in 1980, he realized The New, a series of vacuums and polishers displayed in clear cases, followed just five years later by the Equilibrium series, which included sculptures of balloons floating in water: the first of Koons’ experiments on the fetishist fascination with consumer culture, which he would continue to develop over the years.

In 1986, he would showcase his stainless steel Rabbit in a collective exhibit at the Sonnabend Gallery of New York together with Peter Halley, Ashley Bickerton, and Meyer Vaisman, attracting the attention of critics.

That same year, Koons continued his research on the theme of decadent consumerism — particularly with the series Luxury and Degradation, incorporating images of liquor ads and sculptural renderings of travel bars, and Banality (1988), where he’d create oversized figurine sculptures, including the famous Michael Jackson and Bubbles.

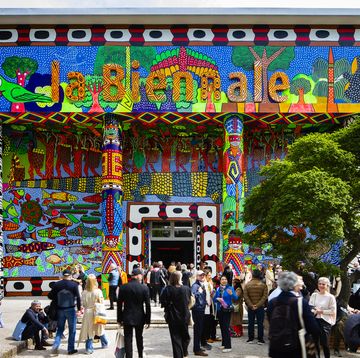

They would be the first formal apparitions of advertising in the artistic language of Jeff Koons, which would also show up in Made in Heaven (1990-91), presented for the first time at the 1990 Venice Biennale: pornographic sculptures of the artist and his then wife, Ilona Staller (La Cicciolina). “When I made it, I was just thinking about the ideas around me. I was involved with banal images. I realised that people respond to banal things; they don’t accept their own history; not participating in acceptance within their own being. I started then to take that into the body. Where do people start to feel guilt and shame and rejection of the self? I wanted to go into Made in Heaven with biology; procreation; looking at nature, and to deal with ideas of the eternal,” he told the Guardian years later in 2015.

In 1992, he brought his Puppy sculpture to Kassel for Documenta 9, a 12 meter tall West Highland Terrier made of dirt and flowers. The piece was such a success that after the exhibit it was displayed in other cities like New York, Sydney, and Bilbao.

Over the last few years, Koons has reappeared on the international stage thanks to his exorbitantly priced pieces and the vibrantly colored Bouquet of Tulips (inspired by the Statue of Liberty), installed in Paris in 2016 as a memorial to the victims of France’s recent terrorist attacks.

The work of Jeff Koons has also garnered its fair share of controversy. In a review of his exhibit at the Whitney, The New York Review of Books wrote: “Imagine the Jeff Koons retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art as the perfect storm. And at the center of the perfect storm there is a perfect vacuum. The storm is everything going on around Jeff Koons: the multimillion-dollar auction prices, the blue chip dealers, the hyperbolic claims of the critics, the adulation and the controversy and the public that quite naturally wants to know what all the fuss is about. The vacuum is the work itself, displayed on five of the six floors of the Whitney, a succession of pop culture trophies so emotionally dead that museumgoers appear a little dazed as they dutifully take out their iPhones and produce their selfies”.

The Spectator has defined him “a slick brand manager rather than a tormented creative soul,” while for Roberta Smith, “Mr. Koons is a famous perfectionist who takes many years (“Play-Doh” is dated 1994-2014), spends much money and often ends up inventing new techniques to get exactly what he wants in both his sculptures and his paintings, which are made by scores of highly skilled artists whom he closely supervises”.

However you look at it, the career of Jeff Koons is truly one of a kind, whose rise to success is owed to the opening of roads that once seemed closed by minimalism: the proposition of something new, both accessible and avant-garde.