By: Jacob Watts, EBIO PhD Student

During May 2023, undergraduate and graduate students at the

University of Colorado-Boulder’s Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Museum and Field Studies programs had the opportunity to traverse the state during a camping-style field biology course. This course, Colorado Field Botany, emphasizes the biodiversity, ecology, and evolution of the flora of Colorado. It was taught by CU botanist, lichenologist, professor, and curator Dr. Erin Manzitto-Tripp and her outstanding graduate student Teaching Assistant, Adele Preusser, and consisted of three 1-week sections. Weeks 1 and 3 were week-long camping trips across Colorado’s Eastern Slope and Western Slope, respectively, while Week 2 consisted of local botanizing and independent study. The course’s only textbooks were Weber and Wittmann’s Colorado Flora: Eastern and Western Slope editions. On May 15th, the class caravanned to its first destination: the Comanche National Grasslands in the southeastern plains of Colorado. Once there and without delay, with the help of these field guides and knowledgeable and patient teachers, we began to ‘key’ plants as a group, learning myriad botanical terms and concepts along with important concepts in plant ecology.

When using dichotomous keys, our group of amateur botanists was presented with a series of forks in the proverbial road to lead us to the identity of the plant confronting us. With 3,100 seed plant species in Colorado to choose between, and little to no prior experience in the botanical sciences (Erin believes in botany without borders – no prerequisites were required!), one can imagine that this was at first a daunting task. However, students learned exceptionally quickly in the field, which is perhaps unsurprising given the overall efficacy of outdoor and experiential learning. Dichotomous keys use defining characteristics of a given species to whittle down the list of possible identities in the form of contrasting “couplets”. For example, a key might describe plants as having parallel vs. netted leaf veins. This single characteristic would guide the reader to select either monocots or dicots, greatly reducing the pool of possible identities. The key then proceeds with increasingly nuanced features that ultimately reveal its identity. Some difficulties arose when terms became highly technical or when the mystery plant seemed intermediate between the two options presented in a given couplet. It was at these moments that Erin and Adele would step in and provide direction. Many a heated debate arose between students about the density of trichomes on the abaxial surface of the leaves, or what Weber and Wittmann meant by “chaffy pappus”! Through this process, repeated 20, 30, or even 40 times a day, we simultaneously learned plant names, technical botanical lingo, and emergent biological concepts (e.g., reproductive isolation, breeding system evolution, determinants of range size) at a blistering pace. We even began to skip parts of the key, as we could recognize the cross-shaped flowers of the mustard family (Brassicaceae) or the bilaterally symmetrical flowers characteristic of the pea family (Fabaceae), despite most students not having any prior experience.

We spent our days hiking and driving to search for new and interesting plants whereas our mornings and evenings were spent around camp, preparing meals while botanizing our meal ingredients and local habitats. We intimately engaged with the outdoors. We became students of the flora and the ecosystems the surrounded us. Hours were spent with craned, sunburned necks and single eyes closed, peering through handlenses at tiny floral parts. It was not uncommon to drive hours out of the way to explore different and interesting habitats where we found new communities of flowering plants. Our “where to go” choices, although seemingly limitless in this vast state, were governed by the edaphic and/or climatic differences between sites along with camping accessibility. Immediately and without prompting, once camp was reached students would excitingly set out to explore and learn new plants on their own or in small groups. We talked about plants around the fire, in the form of our “Fireside Chat” assignments given to us as part of the syllabus and learning goals. Plants were the butt of all jokes. It was as if the class had formed a band of plant-crazed botanists living their best lives together in the Colorado wilderness. It was a much-needed break from society for all of us and an entrance into nature and all it can teach.

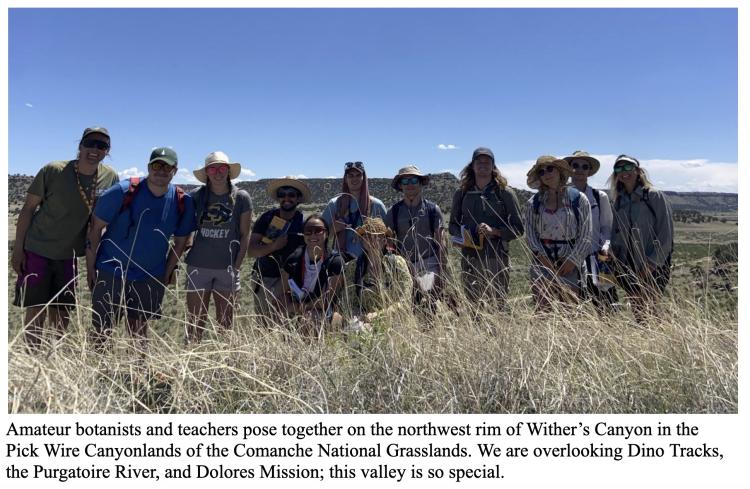

And boy did nature teach! All we needed to do was look closely. During Week 1, we visited Withers Canyon in the Comanche National Grasslands, Great Sand Dunes National Park in the heart of the San Luis Valley, and a stunning Bureau of Land Management (BLM) campsite just north of Cañon City. Between each campsite, we made stops at points of botanical interest. Bushwhacking and traversing 12 trail-less miles through Withers Canyon with little-to-no shade on Day 1 proved challenging yet fruitful. We saw (or accidentally kicked!) nearly every cactus species in Colorado on one hike, learned close to 10 new plant families on this given day, stood where dinosaurs once stood on the banks of the Purgatoire River (a tributary of the Arkansas), and took a much-needed cold soak in the river. We welcomed the sunset after that long and grueling day, as temperatures plummeted and spirits rose. One day later, after a hint of car trouble and a dash of gas station snacks, we found ourselves in the mysterious San Luis Valley, the largest high altitude desert valley in the world. It was in pinyon-juniper (PJ) forest on the western slope of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains that we learned our first member of the Asteraceae and all the botanical jargon that accompanies it, not a mile from a desolate sand-dune habitat nearly devoid of plant life. Our Week 1 trip came to a close after a few soggy nights at a BLM climber’s paradise campsite along Shelf Road north of Cañon City. There we learned some incredible geology along with the tropical remnants of the Colorado Flora, including constituents of the citrus family Rutaceae (Ptelea trifoliata), coffee family Rubiaceae (Galium spp.), and mango/pistacio family Anacardiaceae (Rhus glabra). Limestone bluffs checkered with cushion plants of all kinds towered over red, sandy washes that surrounded us. A member of the most diverse genus in the world, Astragalus (Fabaceae), stumped even our seemingly all-knowing professor and TA. Craving more, we even took late night botany hikes as the rains momentarily let up. As new students of nature, our eyes were opened to the diversity and ecology of plants around us, and we were sent home to discover our hometown Boulder in a brand new, shining light.

At dawn the following Sunday, the summer band of student botanists set out once again, this time for western Colorado, armed with our Western Slope floras, our hype and enthusiasm, and our new appreciation for (and knowledge of) plant biodiversity. Little did we know the day that awaited us, for our campsite lie in an unknown, faraway land. The original intended target was Rifle, CO; however, hordes of Memorial Day campers and public roads turned private prevented the caravan from making camp in the area. In an impromptu yet democratic decision made at a ripe 6:30 PM, the group set our sights on the Book Cliffs north of Grand Junction, a mere two-hour drive from where we had botanized all day. A few moments prior to sunset, we settled on a secluded, idyllic campsite on BLM lands abutting a rare and remarkable ephemeral desert stream. The class was: HAPPY! Desert oasis long sought after. The following day, we hiked from camp into a remarkably steep-walled and narrow desert canyon, keying and learning: Calochortus nuttallii, Ipomopsis agregata, Fraxinus anomala, and others. Late lunch was back at our desert campsite, and to escape the heat, we drove down to the Colorado River for riparian botany and a much-needed dip into the Colorado River, flowing fast and high with flood watches owing to the state’s high snowmelt. Back at camp, sunset brought an exquisite view of the serpentine canyons of the Colorado National Monument while students presented Fireside Chats hiding in the long shadow of a student’s truck. More botany the next day, and two nights later, we headed south for a botanical pit stop in Dominguez-Escalante National Conservation Area. We hiked all afternoon after a 20 mile drive down a terrible dirty road, finding a series of canyon springs and identifying nothing short of 14 species including Yucca harrimaniae, Townsendia annua, and Aquilegia acunifolia. We retreated after a late lunch, making our way to Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park where we would set up camp for the remainder of the course. The upper valley was in full, glorious flower: as floriferous as any of us had ever seen it, reminiscent of the bountiful botany of the Cerrado biome in Brazil. We identified so many species that afternoon including Utah Serviceberry (Amelanchier utahensis) and Arrowleaf Balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sagittata). These plants were so common that they painted the landscape a surreal white and yellow. The next morning, we set out for the biology hike of our lifetimes: descending the S.O.B. Trail, which traverses over 2,000 feet vertical gain in less than a mile (so steep that it is also sometimes called a route rather than a trail). We botanized all the way down, climbing through at least 3 distinct altitudinal zones of plant communities, until reaching the roaring, screaming Gunnison River. People took their time swimming and bathing in the bottom prior to the long, steep, scrambling, four-legged trek back uphill to camp. Deep within the canyon, we found Oenothera caespitosa, Thelypodiopsis juniperorum, Physaria rollinsii, Mahonia repens, Echinocerus coccineus, Opuntia fragilis, and maybe even some new meaning to life.

After traversing much of Colorado with the sole purpose of learning new plants and building our knowledge and appreciation of the native landscapes that surround us, our field practical (given to us in the beautiful, floriferous Black Canyon!), asked us to describe leaf margins, pubescence, shape, floral morphology, and ID plants on our own. The written portion of the exam asked us about what inspires us, what were the primary plant communities we visited, and why did we value learning something new about plant biodiversity. Through those minutes, hours, and days, each one of us had become independent botanists, a beautiful end to the course of a lifetime. All said and done, the course encountered and identified 138 species together! After its conclusion and our return to Boulder, the class stuck together, joining up for dinnertime events and more botanical fun. We are already plotting a July reunion. We are thankful to EBIO and the university for supporting our journey, which left us with many new life skills, perspectives, and memories to last a lifetime.

Comprehensive plant list kept by graduate student and lichenologist Seth Raynor

|

Colorado’s Eastern Slope |

|

|

Quincula lobata |

Solanaceae |

|

Elymus elymoides |

Poaceae |

|

Cercocarpus montanus |

Rosaceae |

|

Physaria calcicola |

Brassicaceae |

|

Penstemon angustifolius |

Schrophulariaceae |

|

Melampodium leucanthum |

Asteraceae |

|

Tradescens occidentalis |

Commelinaceae |

|

Yucca glauca |

Agavaceae |

|

Cylindropuntia imbricata |

Cactaceae |

|

Opuntia polyacantha |

Cactaceae |

|

Opuntia macrorhiza |

Cactaceae |

|

Erysimum capitatum |

Brassicaceae |

|

Convolvulus arvensis |

Convolvulaceae |

|

Adenolinum lewisii |

Linaceae |

|

Sphaeralcea coccinea |

Malvaceae |

|

Vexibia nuttallina |

Fabaceae |

|

Opuntia trichophora |

Cactaceae |

|

Gilia pinnatifida |

Polemoniaceae |

|

Echinocereus viridiflorus |

Cactaceae |

|

Cucurbita foetidissima |

Cucurbitaceae |

|

Nuttalia multiflora |

Loasaceae |

|

Vicia linearis |

Fabaceae |

|

Echinocereus relchebachii var. perbellus |

Cactaceae |

|

Comandra umbellata |

Comandraceae |

|

Calyophus lavandulifolius |

Onograceae |

|

Penstemon buckleyii |

Schrophulariaceae |

|

Castilleja sessiliflora |

Schrophulariaceae/Orobanchaceae |

|

Phlox longifolia |

Polemoniaceae |

|

Eremogone hookeri |

Alsinaceae |

|

Astragalus mollissimus |

Fabaceae |

|

Gaura coccinea |

Onograceae |

|

Sarcobatus vermiculatus |

Chenopodiaceae |

|

Ribes leptanthum |

Grossulariaceae |

|

Populus angustifolia |

Salicaceae |

|

Bromopsis inermis |

Poaceae |

|

Juncus arcticus subsp. ater |

Juncaceae |

|

Populus tremuloides |

Salicaceae |

|

Packera tridenticulata |

Asteraceae |

|

Physaria montana |

Brassicaceae |

|

Prunus virginiana |

Rosaceae |

|

Picea pungens |

Pinaceae |

|

Pseudotsuga menziesii |

Pinaceae |

|

Pulsatilla ludociana |

Rannuaculacea |

|

Philadelphus microphyllus |

Hydrangeaceae |

|

Pennellia micrantha |

Brassicaceae |

|

Juniperus scopulorum |

Cupressaceae |

|

Escobaria missouriensis |

Cactaceae |

|

Pinus edulis |

Pinaceae |

|

Rhus aromatica subsp. trilobata |

Anacardiaceae |

|

Ptelea trifoliata |

Rutaceae |

|

Echinocerus triglochidiatus |

Cactaceae |

|

Quercus gambellii |

Fagaceae |

|

Clamatis hirsutissimus |

Rannuaculacea |

|

Cheilanthes feei |

Cheilanthaceae |

|

Opuntia phaeacantha |

Cactaceae |

|

Opuntia fragilis |

Cactaceae |

|

Tetraneuris acaulis |

Asteraceae |

|

Erodium cicutarium |

Geraniaceae |

|

Populus deltoides subsp. monlifera |

Salicaceae |

|

Astragalus pectinatus |

Fabaceae |

|

Castilleja integra |

Schrophulariaceae/Orobanchaceae |

|

Plantago lanceolata |

Plantaginaceae |

|

Equisetum hymenale |

Equisetaceae |

|

Vitis acerafolia |

Vitaceae |

|

Ulmus pumila |

Ulmaceae |

|

Colorado’s Western Slope |

|

|

Picea engelmanii |

Pinaceae |

|

Aibes lasiocarpa |

Pinaceae |

|

Pinus contorta |

Pinaceae |

|

Hymenopapus filifolius var. megacepholus |

Asteraceae |

|

Taraxacum officinale |

Asteraceae |

|

Sphaeralcea coccinea |

Malvaceae |

|

Sclerocactus parviflora |

Cactaceae |

|

Artemisia tridentata |

Asteraceae |

|

Bromus tectorum |

Poaceae |

|

Alyssum simplex |

Brassicaceae |

|

Erodium cicutarium |

Geraniaceae |

|

Oenothera caespitosa |

Onograceae |

|

Melilotus officinale |

Fabaceae |

|

Penstemon watsonii |

Schrophulariaceae |

|

Symphoricarpus rotundifolius |

Caprifoliaceae |

|

Galium spurium |

Rubiaceae |

|

Lapidium eastwoodii |

Brassicaceae |

|

Mertensia brevistyla |

Boraginaceae |

|

Viola vallicola |

Violaceae |

|

Hydrophyllum capitatum |

Hydrophyllaceae |

|

Claytonia lanceolata |

Portulaceae |

|

Erythronium grandiflorum |

Liliaceae |

|

Noccaea fendleri |

Brassicaceae |

|

Valeriana capitata subsp. acutiloba |

Valerianaceae |

|

Salix |

Salicaceae |

|

Ranunculus alismifolius |

Ranunculaceae |

|

Calochortus nuttallii |

Calochortaceae |

|

Fraxinus anamola |

Oleaceae |

|

Circium tracyi |

Asteraceae |

|

Astragalus linifolius |

Fabaceae |

|

Galium coloradense |

Rubiaceae |

|

Phlox longifolia |

Polemoniaceae |

|

Ephedra viridus |

Ephedraceae |

|

Erigeron concinnus |

Asteraceae |

|

Ipomopsis aggregata |

Polemoniaceae |

|

Sphaeralcea grossularifolia |

Malvaceae |

|

Stanleya pinnata |

Brassicaceae |

|

Lygodesmia grandiflora |

Asteraceae |

|

Eriogonum inflatum |

Polygonaceae |

|

Hesperastipa comata |

Poaceae |

|

Chamaesyce fendleri |

Euphorbiaceae |

|

Phacelia glandulosa |

Boraginaceae |

|

Krascheninnikovia lanata |

Chenopodiaceae |

|

Tetradymia spinosa |

Asteraceae |

|

Xylorhiza venusta |

Asteraceae |

|

Cymopterus planosus |

Apiaceae |

|

Alium nevadense |

Alliaceae |

|

Mirabilis glandulosa |

Nyctaginaceae |

|

Yucca harrimaniae |

Agavaceae |

|

Chamaechaenactis scaposa |

Asteraceae |

|

Penstemon cf. retrorsus |

Schrophulariaceae |

|

Townsendia annua |

Asteraceae |

|

Physaria acunifolia |

Brassicaceae |

|

Aquilegia acunifolia |

Helleboraceae |

|

Alnus incana |

Betulaceae |

|

Eremogone kingii subsp. uintahensis |

Alsinaceae |

|

Oreocarya flavoculata |

Boraginaceae |

|

Toxicoscordion gramineum |

Melanthiaceae |

|

Adednolinum lewisii |

Linaceae |

|

Clematis hirsutissima |

Ranunculaceae |

|

Balsamorhiza sagittata |

Asteraceae |

|

Wyethia arizonica |

Asteraceae |

|

Mahonia repens |

Berberidaceae |

|

Echinocerus coccineus |

Cactaceae |

|

Opuntia fragilis |

Cactaceae |

|

Physaria rollinsii |

Brassicaceae |

|

Thelypodiopsis juniperorum |

Brassicaceae |

|

Phlox hoodyii |

Polemoniaceae |

|

Lepidium montanum |

Brassicaceae |

|

Amelanchier utahensis |

Rosaceae |

|

Pseudocymopterus montanus |

Apiaceae |

|

Lathyrus leucantha |

Fabaceae |

|

Pseudostellaria jamesiana |

Alsinaceae |

|

Lappula redowskii |

Boraginaceae |