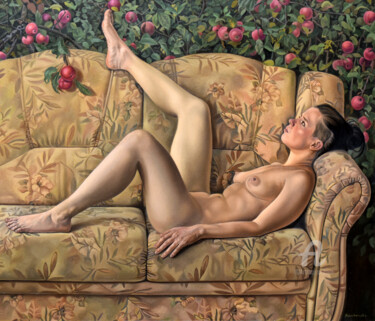

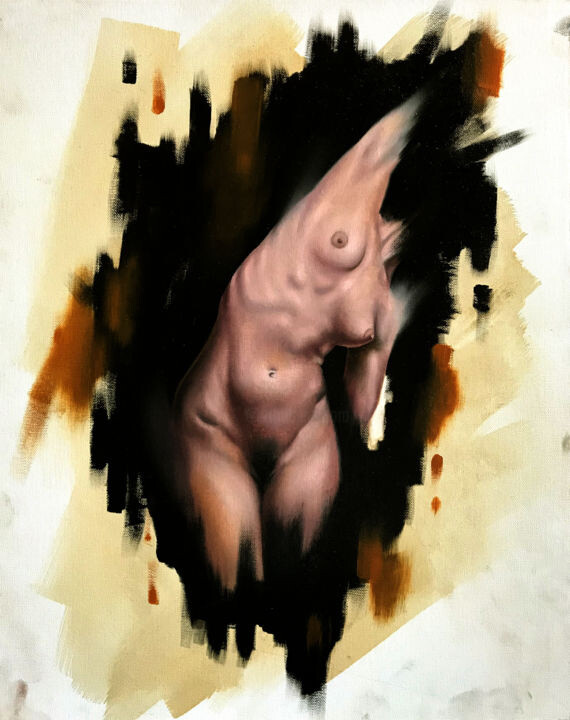

Tsanko Tsankov - Gallery Maestro, White silence, 2020. Oil on canvas, 80 x 110cm.

Tsanko Tsankov - Gallery Maestro, White silence, 2020. Oil on canvas, 80 x 110cm.

The history of female nudity in art is never the same, as different societies and cultures have accepted nude scenes to varying degrees over the centuries and millennia. Indeed, nudity in art reflects the social norms of a given time and place, referring to the ways in which things are represented, indelibly linked to the conception of what is right or wrong to depict. In any case, although nudity is often associated with the most scandalous sexuality, it can also have other meanings, so much so that it is linked to interpretations derived from the realm of mythology and religion, as well as from the study of anatomy and the expression of ideal beauty and aesthetic perfection. These multiple approaches have determined how the female nude has been, and continues to be, the subject of different modes of representation within Western art history.

Jean-Pierre André Leclercq, Courbes 12, 2008. Drawing, Pastel on Cardboard, 60 x 80cm.

Jean-Pierre André Leclercq, Courbes 12, 2008. Drawing, Pastel on Cardboard, 60 x 80cm.

The female nude: between art and obscenity

Although some of the aforementioned types of depictions of the female body appear clearly artistic and hardly scandalous, in most societies of the past women, probably because they enjoyed fewer rights than men, were rarely released from a representation predominantly associated with sexuality. For this very reason, it seems likely that only when women gained greater political rights was the female nude officially, and progressively, accepted in art. The history of the representation of the female body thus seems to go hand in hand with that of emancipation, the stages of which were figuratively marked primarily by Greek, Italian, and French art. It is precisely through these points of view that it will become evident how the role of the nude woman in art is unique, in perpetual balance between art and obscenity. This means that when an artist begins to show a naked woman, he or she automatically walks the razor's edge between artistic and "pornographic" representation.

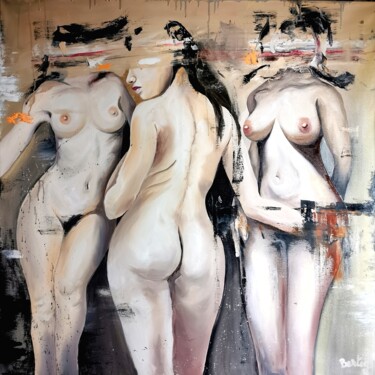

Brigitte Derbigny, Vénus mama, 2020. Drawing, acrylic, spray, pencil, and marker on paper. 100 x 70 cm.

Brigitte Derbigny, Vénus mama, 2020. Drawing, acrylic, spray, pencil, and marker on paper. 100 x 70 cm.

1. Prehistory: the fertility nude and the "realistic" nude

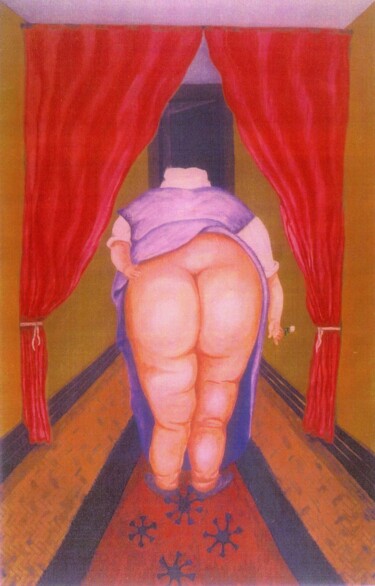

In Paleolithic art, female nudity was closely linked to the worship of fertility deities. This is evident in the earliest representations of the female human body form, which are called "Paleolithic Venuses," characterized by the prorompetent features of obese women with wide hips and breasts, which protrude or hang downward. Most of them date from the Aurignacian period and are made of limestone, ivory or soapstone. The most famous, besides the Venus of Willendorf, are the Venus of Lespugue, the Venus of Savignano, the Venus of Laussel, and the Venus of Doln Vstonice. Speaking of painting, on the other hand, the female nude appears even as far back as rock art, especially that of northern Spain (Franco-Cantabrian area) and the Mediterranean basin, where female subjects are captured within community scenes of hunting or rituals and dances. In the latter contexts, women are immortalized in a more streamlined realistic manner, just as in the example of the Tassili n'Ajjer.

The Prehistoric Rock Art of Tassili N'Ajjer, Algeria. Photo credit: Patrick Gruban/Wikimedia.

The Prehistoric Rock Art of Tassili N'Ajjer, Algeria. Photo credit: Patrick Gruban/Wikimedia.

Rock paintings of the Tassili n'Ajjer

The Tassili n'Ajjer is a mountain range located in southeastern Algeria, near the border with Libya. Much of that plateau, which is home to cypress trees and ancient sites, is protected by a National Park, a Biosphere Reserve and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In terms of female nudity, the Tassili n'Ajjer is known for its rock art, which, dating back 9,000-10,000 years, shows mainly herds of beasts, large wild animals such as elephants, giraffes and crocodiles, and people doing things like hunting and dancing. In this context, it is interesting to observe the image of five bare-breasted, high-haired women, with extremely "realistic" physiques, trying to rest and talk casually.

Pictor Mulier, Cleopatra nude with her leopard, 2017. Acrylic on wood, 80 x 60 cm.

Pictor Mulier, Cleopatra nude with her leopard, 2017. Acrylic on wood, 80 x 60 cm.

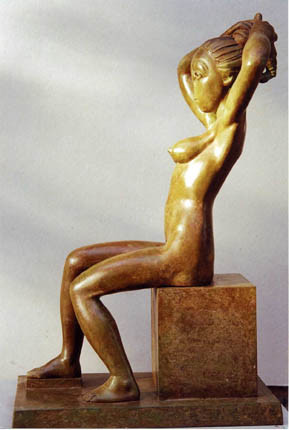

2. Ancient Egypt: beauty to be carried into the afterlife

It is important to note a fundamental element of ancient Egyptian figurative culture: in the works of the period, it is quite rare to find women depicted in their later or mature years. In fact, female characters were depicted slender, beautiful and in their prime, features that, precisely because they were immortalized by art, it was hoped that they could be assumed by the effigy even in the afterlife. In general, Egyptian art was anything but realistic, as this civilization was extremely concerned with how it was perceived. In fact, there are almost no images of pregnant women or female bodies after childbirth, in order to be able to exclusively immortalize people at the height of their beauty and youth. Nevertheless, in the Third Intermediate Period, scholars noticed a change in artistic style aimed at depicting women. It was precisely in that era that a more rounded, thickened body type appeared, with larger, drooping breasts. About the uncovered body, on the other hand, nudity was normal at that time, so much so that certain social statuses, as well as some specific tasks, such as fishing and manual labor, required the body to be unclothed. Speaking of work, servants, dancers, acrobats and prostitutes went about completely or mostly naked, as evidenced by the "Naked Dancers" depicted in a painting from the Tomb of Nebamun (c. 1350 BCE).

Nebamun tomb fresco dancers and musicians, 18th dynasty. London: British Museum.

Nebamun tomb fresco dancers and musicians, 18th dynasty. London: British Museum.

The lost Tomb of Nebamun was an ancient Egyptian burial ground of the 18th Dynasty, which was found in the Theban necropolis on the west bank of the Nile, a location today identifiable with the present-day city of Luxor (Egypt). From this tomb come some famous decorated tomb scenes, which can currently be admired at the British Museum in London. In the latter place it is possible to admire the plastered walls of that tomb, covered with vivid frescoes, showing idealized scenes of the life of the time and its activities. Among them, some of the most famous paintings turn out to be those depicting hunting scenes and semi-naked dancers at a banquet.

Monika Mrowiec Monika Mrowiec, Venus de Milo, 2021. Painting, Spray / Acrylic / Ink / Oil on Canvas, 140 x 90cm.

Monika Mrowiec Monika Mrowiec, Venus de Milo, 2021. Painting, Spray / Acrylic / Ink / Oil on Canvas, 140 x 90cm.

3. Ancient Greece: the body like that of Aphrodite

In ancient Greece, the ideal woman had to have soft forms, enhanced by round buttocks, long hair with waves, and a flawless beautiful face. Such requirements suited a time when having more fat on the body meant being wealthy, that is, being able to afford to eat well, distinguishing oneself from the lower and hungrier social classes. In this context, Aphrodite, goddess of love, sex, beauty and fertility, was depicted with a round face, large breasts and a pear-shaped body. The undisputed figurative model of such canons is Praxiteles' Aphrodite cnidia, a work that, at the same time, is very important since it was the first to break the mold by introducing the female nude into Greek art. Indeed, Greek society had previously depicted predominantly the male sex, limiting female nudity to scenes of captivity, submission, and small scale.

Attributed to Onesimos (Greek (Attic), active 500 - 480 B.C.), painterAttic Red-Figure Kylix, about 490 B.C.Terracotta, 8.5 × 36.9 cm (3 3/8 × 14 1/2 in.)The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California, 82.AE.14

Attributed to Onesimos (Greek (Attic), active 500 - 480 B.C.), painterAttic Red-Figure Kylix, about 490 B.C.Terracotta, 8.5 × 36.9 cm (3 3/8 × 14 1/2 in.)The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California, 82.AE.14

Attic red-figure kylix of Onesimos

An example of these early approaches to the female nude in painting is the red-figure Attic Kylix, attributed to Onesimos (500 - 480 BCE), a work in which a nude, reclining woman is playing kottabos, a popular activity in the masculine symposium festival. In fact, following the tradition of the event, the girl with the handle of a deep cup (skyphos), attached to her index finger, tries to throw leftovers from the bottom of the cup toward a distant target. In this context, however, it is important to point out that, the symposium was actually exclusively for men, such that female presences were usually on site to entertain the men. Indeed, the nudity of the aforementioned would have been too risqué for the respectable women of Athens, but it could have been afforded to slaves hired as prostitutes, or to "etere," wealthy women who enriched the evening of male drinking by singing, talking, and showing sexual attractiveness.

Tito Villa, Pompeii wall painting, Open edition. Digital arts, giclée print / digital Print, several sizes available.

Tito Villa, Pompeii wall painting, Open edition. Digital arts, giclée print / digital Print, several sizes available.

4. The Roman world: the erotic art of Pompeii and Herculaneum

Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum was brought to light through a long series of archaeological excavations that began in the 18th century. This very activity revealed how the said site was rich in erotic art, depicted both in the form of frescoes and sculptures. The peculiarities of such subjects indicate that Roman customs were more liberal than in most cultures known to us, although it should be emphasized that many of what might seem to us to be exclusively erotic images might in fact be symbols of the fertility of nature in the broadest sense, as well as talismans of good luck and auspiciousness.

Venus in a shell, fresco. Pompeii: House of the Venus in a shell.

Venus in a shell, fresco. Pompeii: House of the Venus in a shell.

Fresco of the Venus in a Shell - Pompeii

The House of the Venus in Shell, a site discovered between 1933 and 1935, features a large peristyle, which is essentially the center of the domus. This very room was overlooked by the various rooms of the house, having walls decorated in the Pompeian IV style. In reality, however, the house is named after its most famous fresco, namely the Venus in a shell, which, compared to the eroticism prevalent in the ancient Roman city, turns out to be rather demure. In fact, the nude Venus is simply lying in a shell, while accompanied in the act of birth by a cupid and a child, presumably baby Mars.

Miguel Rojas, Adam Eve, 2022. Drawing, Ink on Paper, 20.5 x 12.5cm.

Miguel Rojas, Adam Eve, 2022. Drawing, Ink on Paper, 20.5 x 12.5cm.

5. Medieval age: the nakedness of Eve

In medieval times, following the spread of culture derived from Christianity, the body began to be intense as the sacred temple of the soul, which had to be preserved at all costs from carnal impulses, harbingers of grave sins in the sight of God. Despite such assumptions, vice continued to run rampant, so much so that it was in the sensuality of the female body, derived from the sinful Eve, that the devil and the personification of lust was identified. For this reason, the medieval era presents many works, depicting the progenitor, often depicted in her naive and immature nakedness, already capable of grasping the apple of sin.

Masaccio, Expulsion of the progenitors from Eden, 1424-25. Fresco, 214 x 88 cm. Florence: Brancacci Chapel (church of Santa Maria del Carmine).

Masaccio, Expulsion of the progenitors from Eden, 1424-25. Fresco, 214 x 88 cm. Florence: Brancacci Chapel (church of Santa Maria del Carmine).

Expulsion of the progenitors from Eden (1424-1425) by Masaccio

The Expulsion of the progenitors from Eden is a fresco by Masaccio, located in the Brancacci Chapel of the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. It shows Adam and Eve after they have broken God's rules and thus eaten the fruit of knowledge. In fact, they are shown naked and helpless as they are taken away from the Earthly Paradise. In reality, however, it is good to highlight how, in the Bible's account, Adam and Eve crossed the threshold of Paradise clothed.

Masolino, Temptation of Adam and Eve, 1424-25. Fresco, 260 x 88 cm. Florence: church of Santa Maria del Carmine.

Masolino, Temptation of Adam and Eve, 1424-25. Fresco, 260 x 88 cm. Florence: church of Santa Maria del Carmine.

Temptation of Adam and Eve (1424-25) by Masolino

In the same chapel as Masaccio's Expulsion of the progenitors from Eden, there is another work with a "related" theme: The Temptation of Adam and Eve or Original Sin, a work by Masolino from around 1424-1425. The fresco shows a famous scene from the Old Testament, namely when the serpent from the book of Genesis tries to convince Adam and Eve to break the rules. This episode, set in the late Gothic style, is characterized by the light, which shapes the figures in a soft and enveloping way, just as if they emanated a diffuse glow. In addition, the dark background enhances the sensual plasticity of the nudes of the two sinners.

Nagy Peter, Venus, 2021. Painting, Acrylic / Marker on Canvas, 40 x 50 cm.

Nagy Peter, Venus, 2021. Painting, Acrylic / Marker on Canvas, 40 x 50 cm.

6. The Renaissance era: the beginning of sensuality

From the end of the Middle Ages to the beginning of the Renaissance, the standards of women's beauty changed dramatically: they went from pale, skinny models with barely visible breasts to fleshy females with wide hips and lips and cheeks painted red. Most patrons of the time could not resist such aesthetic canons, so much so that they demanded sacred subjects as an excuse to contemplate the aforementioned sensuality. In this Christian context, nudity increasingly became a sign of sanctity, purity and mortification of the body, and, if understood outside of this sphere, it was interpreted as an obvious reference to the most unscrupulous lust and lasciviousness. Similarly, at the time nudes were accepted, and not demonized, if linked to a specific allegory or the re-enactment of a mythological event. An example of the above is the celestial, asexual creature in Botticelli's Venus, a work sharply at odds with late Renaissance tendencies, well exemplified by Titian's more “provocative” Venus of Urbino.

Sandro Botticelli, Birth of Venus, 1485. Tempera on panel, 172.5 x 278.5 cm.

Sandro Botticelli, Birth of Venus, 1485. Tempera on panel, 172.5 x 278.5 cm.

The Birth of Venus (1476- 1487) by Sandro Botticelli

In the center of the painting, Venus, standing on a shell as she emerges from the water, appears to move as if floating lightly on the waves. The goddess is nude, surrounded on the right side of the canvas by Zephyrus, who, intent on holding the nymph Clori, blows toward Venus. The idea for this masterpiece was taken from Ovid's Metamorphoses, In fact, the Latin writer recounted that Venus, Roman goddess of Love, was born directly from the foam of the ocean, off the coast of the island of Cyprus. It is precisely at the latter destination that the goddess of Botticelli, master, seems to land, who, in the conception of such a masterpiece, was inspired by the neo-Platonic culture prevalent in the Florence of the time, within which triumphs the thought, according to which, love represents a vital principle and the force of the renewal of nature.

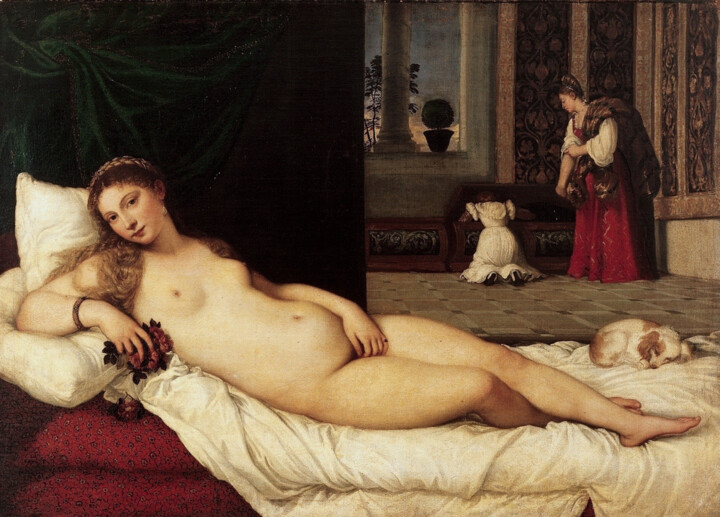

Tiziano Vecellio, Venus of Urbino, 1538. Oil on canvas, 119 x 165 cm. Florence: Uffizi Gallery.

Tiziano Vecellio, Venus of Urbino, 1538. Oil on canvas, 119 x 165 cm. Florence: Uffizi Gallery.

Venus of Urbino (1538) by Titian Vecellio

The Venus of Urbino is a perfectly balanced painting, whose composition does not detract from the sensual naturalness of the effigy, portrayed without any clothing as she lies on a mattress covered in floral-patterned fabric with a white sheet on top. Against this backdrop, Venus, who is wearing precious details and has her hair partly pulled back to form a scrunchie that crowns the nape of her neck, leans against two pillows in order to support her upper body. The face of of of the goddess, who sensually covers her pubis with her left hand, is turned forward, as if she wanted to look directly at the viewer. In the room housing Venus, richly furnished in the Renaissance style, one also glimpses the presence of a small dog and two handmaids, intent on extracting clothes from a chest. More accurately interpreting Titian's intentions, the work was created at the behest of Guidobaldo, who wished to use the masterpiece as an example of married life to propose to his wife Giulia da Varano. Therefore, in order to satisfy the patron, the Italian artist actualized the classical figure of Venus, stretching her in a 16th-century setting and making her the bearer of an innovative moral message. In fact, the presence of roses alludes to beauty, while that of the dog refers to fidelity, a less affimera, but hopefully more lasting, peculiarity.

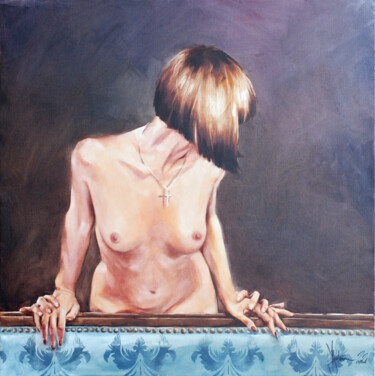

Niko Sourigues, Standing nude, 2017. Oil on Canvas, 41 x 33 cm.

Niko Sourigues, Standing nude, 2017. Oil on Canvas, 41 x 33 cm.

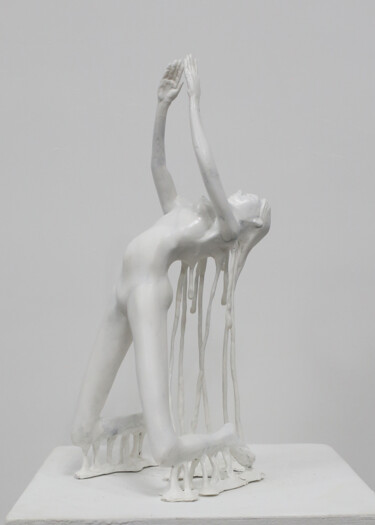

7. Mannerism and Baroque: the sensuality of twisting and dynamism

Mannerism is an artistic current, first Italian and then European, whose origins date back to the 16th century. The female nudes of this figurative trend were predominantly placed within complex compositions, studied to the point of being artificial, since they are marked by constructed perspective distortions, in which the eccentric arrangement of the subjects, rendered through the typical serpentine figure, realized as the dynamism of a fire flame, stands out. Adding to the "twisted" sensuality is an accurate use of light, aimed at emphasizing expressions and movements, at the cost of being sometimes unrealistic. It is worth highlighting how such peculiarities will be inherited by the subsequent and related Baroque period, within which, the female nude, made even more erotic by the accentuation of Mannerist sensuality, continued to be exploited to immortalize mainly mythological and allegorical themes.

Bronzino, Allegory with Venus and Cupid, 1540-45. Oil on panel, 1.46 x 1.16 m. London: National Gallery.

Bronzino, Allegory with Venus and Cupid, 1540-45. Oil on panel, 1.46 x 1.16 m. London: National Gallery.

Allegory with Venus and Cupid (1540 1545) by Bronzino

"Naked Venus with Cupid kissing her, and Pleasure on one side and Enjoyment with other loves, and on the other side Fraude, Jealousy et other passions of love." Giorgio Vasari's description introduces us to Bronzino's Allegory with Venus and Cupid, a work commissioned around 1540 by Cosimo I, the second and last duke of the Florentine Republic, who wanted to pay homage, through the gift of the aforementioned masterpiece, to the King of France Francis I, in order to win himself advantageous political opportunities. It is precisely this intent that makes the work, which immortalizes Venus vanquishing Cupid, still unclear in its meaning, so much so that the subject depicted may have been elaborated by a literary person, probably a member of the thriving cultural milieu of the 16th-century Medici court. Speaking of the description of the masterpiece, the oil depicts Venus and Cupid, the undisputed protagonists of the painting, who have been immortalized without clothes, while their bodies, so cold as to look like wax sculptures, harmoniously intertwine with each other, so much so that the goddess seems to assume the contorted pose of a sensual serpent. In this languid atmosphere Venus and Cupid come to kiss, by means of a confused intercourse, as it is too sensual to be a manifestation of the chaste love between mother and son. The ambiguity of the two protagonists is compounded by that of the characters around them, as well as the masks resting on the ground. Indeed, the maiden-faced monster, having in one hand a sweet honeycomb in the other a poisonous stinger, becoming probable personification of "deception," while the masks allude to the fact that everything in this scene is an act. Just, Venus and Cupid, if well observed, reveal their impending betrayal of each other: as they kiss, she pulls an arrow from his quiver and he, at the same time, is about to steal the diadem from her hair.

Peter Paul Rubens, Venus in the Mirror, 1613/14. Painting. Vienna: Liechtenstein Museum.

Peter Paul Rubens, Venus in the Mirror, 1613/14. Painting. Vienna: Liechtenstein Museum.

Venus in the Mirror (1613-14) by Peter Paul Rubens

In the Flemish master's sensual masterpiece, the mirror is used to show the beauty of the goddess from different points of view. Such a perspective stratagem takes place in a private life scene, within which the goddess is shown from behind wearing only a white veil, which encircles her hips. It is precisely through the over-handled mirror, supported by a cupid, that one can become acquainted with the perfect face of Venus, distinguished by its regular oval, enlivened by the presence of rosy cheeks and a concentrated gaze, which is accompanied by a hint of a smile. The sensuality of this voyeuristic atmosphere is enhanced by the sinuous movement of the long blond hair, carefully crafted as if it were thin strands of gold. Finally, such a masterpiece turns out to be clearly inspired by Titian and Veronese, as the warm light and bright colors create striking color contrasts designed to further highlight the beauty of the goddess.

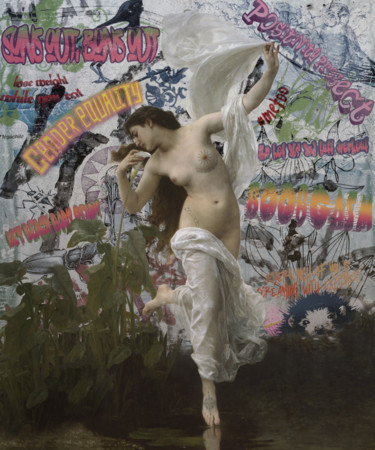

Naïs Philip, Venus, 2020. Oil on Linen Canvas, 97 x 146 cm.

Naïs Philip, Venus, 2020. Oil on Linen Canvas, 97 x 146 cm.

8. Romanticism and Realism: a little bit explicit

The female nude, beginning in the second half of the eighteenth century, that is, coinciding with the advent of the Age of Enlightenment, became untethered from myth, just as demonstrated, for example, by the artistic investigation of François Boucher who, in works such as Brown Odalisque (1745) and Fragonard (1765-72), painted ordinary young women caught in intimate and highly sensual settings. Such a free and bold narrative of femininity continued with great success in Romanticism and Realism. In the former of the latter two artistic movements, the female nude became highly expressive, as Romanticism strongly emphasized color in order to achieve more dramatic depictions, apropos of subjects exploring multiple themes, such as Orientalist, strange, mysterious, tragic, heroic, and extremely passionate ones, aimed at exalting the purest freedom of expression of the human being. As for realism, on the other hand, it is well summarized through the analysis of the figurative investigation of Gustave Courbet, the father of the movement that overcame the "Romantic and Classicist errors" in order to bring greater fidelity to the rendering of the real datum in the nude, overcoming that idealized concenzione of the female body.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Great Odalisque, 1814. Oil on canvas, 91 x 162 cm. Paris: Louvre Museum.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Great Odalisque, 1814. Oil on canvas, 91 x 162 cm. Paris: Louvre Museum.

The Great Odalisque (1814) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Sandwiched between Neoclassicism and later Romanticism is one of the best-known nudes in art history, namely Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres' The Great Odalisque, an oil on canvas kept at the famous Louvre Museum in Paris. The protagonist of this masterpiece is a beautiful young odalisque, who has been captured at the moment when she is comfortably lying on a bed covered with thin sheets. As for her supine nudity, it, echoing classical models, borrowed from the Greeks, turns out to be clean, elegant and refined. In fact, the odalisque's most intimate parts have been cleverly concealed, so that only the lower part of one breast is visible. Speaking of the gaze, the raggazza, seen in three-quarter view, exposes her beautiful face to the viewer, to whom she also directs her eyes, framed by the presence of beautiful turban, which, tied around her head, hides most of her hair. Finally, such an image is clearly the result of the influence that the Eastern world exerted on the French master, a reality that he probably got to know through Napoleon's campaigns in the East.

Goya, Maja desnuda, 1790-1800, oil on canvas, 95 x 190 cm. Madrid, Museo del Prado.

Goya, Maja desnuda, 1790-1800, oil on canvas, 95 x 190 cm. Madrid, Museo del Prado.

Maja desnuda (ca. 1790) by Francisco Goya

Maja desnuda and Maja vestida are two paintings by Francisco Goya, which, made in the late 1700s and early 1900s, can both be seen at the institution of the Prado Museum in Madrid. In the first masterpiece by the painter who anticipated Romanticism, the pose of the woman, in this case nude, is the same as in the second: the woman lies on a sofa with her arms behind her head while surrounded by a dark background. Almost certainly these two sensual paintings were commissioned by Manuel Godov, the Spanish prime minister, a very powerful person who could afford to go against the conservatism of the Church. In spite of this, the daring works were seized and later required by the Inquisition Tribunal, which had banned nude images without allegorical or mythological pretexts throughout Spain. Regarding the identity of the model, many accounts of the time recognize in her features Maria Teresa Cayetana de Silva, duchess of Alba who used to host at her home famous politicians and artists, among them, also Francisco Goya, painter with whom she had a passionate relationship.

Gustave Courbet, The Origin of the World, 1866. Oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm. Paris, Museé d'Orsay.

Gustave Courbet, The Origin of the World, 1866. Oil on canvas, 46 x 55 cm. Paris, Museé d'Orsay.

The Origin of the World (1866) by Gustave Courbet

Gustave Courbet's The Origin of the World is a painting that shows, in the perspective of a realistic close-up, the pubic area of a woman's body, sensually surrounded by the adjacent breasts and thighs, which appear naturally, and comfortably, lying on a disheveled white sheet. Such an extremely innovative subject caused a scandal at the time of its creation, as it offered an almost extremely correct, and unfiltered viewpoint of the female body, which was taken, for the first time, in a context, and from an angle, that was extremely intimate and private, capable of revealing to us what was concealed between the legs of the effigy. In reality, however, it should be emphasized that The Origin of the World is not a pornographic work, as it is the result of the artist's diligent study, which focused on rendering the features of reality as best as possible. The intent just mentioned was achieved through a careful study of representation, as well as the use of the Italian technique of tonalism, which transform the masterpiece into a work of great technical expertise. In addition, the potentially scandalous meaning could be replaced by the depiction of an authentic metaphor, that of the great magic of female reproduction. Nonetheless, even today, the strong realism with which the model, probably Constance Queniaux, a dancer at the Paris Opera, was painted, makes the painting "uncomfortable" to look at, when in fact, the most scandalous work of the 19th century also tells another story: that of the spread of the first erotic photographs, which took place precisely at the time of the masterpiece's conception!

Trnski Velimir, Bath in the forest, 2021. Acrylic on Canvas, 58 x 40 cm.

Trnski Velimir, Bath in the forest, 2021. Acrylic on Canvas, 58 x 40 cm.

9. Impressionism and the School of Paris: the prostitute models.

The Impressionists' works often show nude women, even though this type of subject made the Academy and Parisians in general uncomfortable, so much so that in 1863, that is, when Manet's Breakfast on the Grass was exhibited, the painting caused a major scandal, due to the fact that the nude woman in the masterpiece appeared sitting on the grass with two members of the Parisian bourgeoisie. The problem was that the model, who was neither a nymph nor an allegorical figure, subjects favored by academic artists who sought to emulate the great artists such as Raphael, appears to pose with the attitudes of a prostitute, whose gaze is provocatively directed toward the viewer, just as if she wanted to invite him to the "banquet." Justifying this interpretation would also be the fact that Manet painted a frog in the work, an animal that, in the language of Paris at the time, alluded precisely to the figure of the prostitute. Finally, it is worth noting how this type of female subject would persist in the master's work, just as evidenced by Olympia, an oil of 1863 that depicts a woman in an even more explicit and shameless attitude, a warning of a bad reputation. Subsequent to the Impressionists, the artists of the Paris School, a group born in the early 20th century, continued to scandalize with their female nudes, just as the case of Amedeo Modigliani demonstrates.

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863. Oil on canvas, 130.5 x 190 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay.

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863. Oil on canvas, 130.5 x 190 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay.

Olympia (1895) by Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet's Olympia is a well-known painting whose innovative style, a precursor to Impressionism, and the female subject depicted, probably a prostitute, caused much discussion at the 1865 Paris Salon. In the work, the maiden in question is captured as she is sensually reclining on a bed, a location from which she casts a sharp glance at the viewer. In addition, the protagonist, whose face shows no emotion, wears, in her total nudity, only clogs, a bracelet, pearl earrings and a thin black string tied around her neck. In this context, it is worth noting how in this masterpiece, in which a black woman and a black cat also appear, Manet proposed a new way of looking at naked women, representing them in a direct, raw way that was uncompromising with the morals of the time. In fact, instead of the classic idealized nude, he proposed the cold and realistic image of a young prostitute, whose figure was not revisited with mythological, allegorical or symbolic intentions. In addition, precisely the classic pose of the demure Venus, that is, the Venus with her hand on her pubis, is taken up in this decidedly more earthly context.

Edgar Degas, The Tub, 1886. Pastel on cardboard, 60 x 83 cm. Paris: Museo d'Orsay.

Edgar Degas, The Tub, 1886. Pastel on cardboard, 60 x 83 cm. Paris: Museo d'Orsay.

The Tub (1886) by Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas was extremely interested in and attracted to Parisian life, even the city's most intimate and hidden life, an aspect that is highly noticeable in his series of "voyeuristic" paintings, aimed at portraying nude women who, inside their homes, were grappling with dressing. The 1886 pastel, titled The Tub, reinterprets the aforementioned subject, so beloved by Renaissance artists, through a novel cut of the composition, aimed at breaking the traditional rules of the nude, in order to show a woman's body as seen from above. In fact, the young woman is depicted folded in on herself, with her left hand on the basin and her right hand on her hair. In addition, her face is hidden by a knowing shadow, while her beautiful back curves like an arch, showing off her neck and buttocks.

Amedeo Modigliani, Nu couché, 1917-18. Dipinto.

Amedeo Modigliani, Nu couché, 1917-18. Dipinto.

Outrageous Nudes by Amedeo Modigliani

In 1917 Leghorn artist Amedeo Modigliani, also known as Modì and Dedo, held a solo exhibition at the Berthe Weill Gallery in Paris. On this special occasion, Léopold Zborowski, a Polish art dealer who sold the young Italian's works to the aforementioned business, was commissioned to set up the said event. Prior to this project Modigliani had never been exhibited before, so much so that the one at the Weill represented his first ever solo exhibition. Despite the "inexperience" this was a fiery debut, as the nudes displayed in the window, unusually beautiful and far from the norms of the time, led to the intervention of the police, who proceeded to have the windows lowered and those scandalous visions disrupted. The funny thing is that when Berthe Weill asked the officers what was so shocking about a series of nudes, that is, subjects that have been painted for thousands of years, they replied, "there is that those nudes have hair." For this reason, the first exhibition of Modigliani's nude paintings was canceled before it even began.

Victor Molev, Kabbalah, 2020. Painting, Oil on Canvas, 28 x 36 cm.

Victor Molev, Kabbalah, 2020. Painting, Oil on Canvas, 28 x 36 cm.

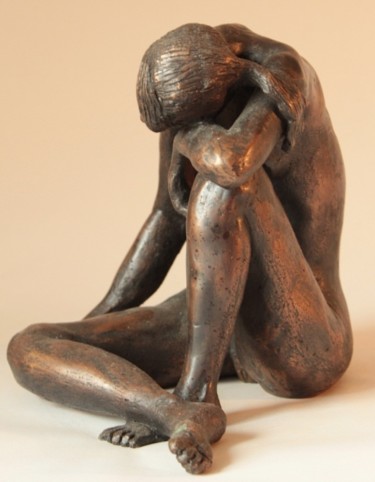

10. Expressionism and Surrealism: personal and visionary interpretations

Among the avant-garde movements of the 20th century, the Expressionist and Surrealist nudes are distinguished by their sensuality, hidden meanings, allusions, and links to the artist's inner and innermost world. With regard to Expressionism, the nude tends to express, through the body, the artist's individual feeling, rather than a mere objective representation of the anatomical datum. For example, anguish, sadness, and existential drama are the main themes of Edvard Much's artistic investigation, feelings that he reproposes in Puberty, an 1894 work aimed at immortalizing a naked teenage girl. Similarly, the artists of Die Brücke (German Expressionism) also often portray naked adolescent girls, just as Kirchner, who in 1910 produced Marcella, a work in which a young girl is depicted with simplified forms, sharp, ringing colors, and a strong, expressive stroke. Finally, another expressionist is Schiele, an artist whose theme of female corporeality was one of the most popular, rendered through the fusion of sexuality and torment. As for Surrealism, on the other hand, this artistic current's vision of the female nude can be summarized through the work of its most famous master, namely Salvador Dali, an artist who approached femininity through a poetic focus on the unconscious and dreamlike dimension of the human being.

Edvard Munch, Puberty, 1894–95. Oil on canvas, 151.5 × 110 cm. Oslo: National Gallery.

Edvard Munch, Puberty, 1894–95. Oil on canvas, 151.5 × 110 cm. Oslo: National Gallery.

Puberty by Munch (1893)

The female nude, as well as the theme of sexuality, is investigated in the painting Puberty, made by Munch in 1893. The first version of this subject was made in 1885 or 1886, but it was lost, so that, over time, the master reproduced it in several works. In the 1893 painting, a teenage girl, portrayed inside a bare place, appears seated on the edge of the bed, while, alone and naked, she has her legs together and her arms crossed over her pubis. In this pose, her eyes are wide open and her mouth is clamped shut, as if to suggest a disturbed emotional state, probably due to the immaturity of her body, illuminated by a light coming from the left, aimed at generating an eerie and threatening shadow. It is precisely this last dark area that seems to allude to the girl's future, which is projected to be dramatic or even tragic. Indeed, the sense of the work might be to recognize in puberty the power to transform innocent girls into women, whose sexuality can be a tool, either of pleasure or pain, for their male counterparts.

Salvador Dalì, Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee, 1944. Oil on wood, 51× 40.5 cm. Madrid:Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum.

Dream caused by the flight of a bee (1944) by Salvador Dali

In the rich, dreamlike and surreal composition of Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee, a 1944 work by Salvador Dali, we also find the nude, outstretched body of a woman, intent on floating on a rock in the middle of the sea. The tranquility of such a subject is quite unimaginable, if, as in the painting, we imagine the sudden approach of two huge and ravenous tigers, as well as the coming of a bayonet gun, the tip of which is even about to touch the woman's arm. In addition to these, there are multiple images that appear in the painting, so much so that the work seems to have been conceived from a dream, a reality in which strangeness follows one another while referring to the real world. In fact, the masterpiece originates from the account of a dreamlike event that happened to the Spanish master's beloved, namely Gala, who, due to the buzzing of a bee, which was flying around her ear, limmaginated all the above visions in succession.

Andrea Vandoni, The laziness, 2022. Oil on Canvas, 73 x 116 cm.

Andrea Vandoni, The laziness, 2022. Oil on Canvas, 73 x 116 cm.

11. Contemporary art: freedom of expression and multiple points of view

Contemporary artists can represent the female nude, either by referring to the great figurative tradition of the past or by expressing themselves through free and innovative points of view. In either case, the purpose of such investigation, having as its subject the woman, is to reveal the likeness of that, which, according to the artist, could express the purest idea of femininity, capable of animating, intriguing, attracting and moving their imagination. In this context, it is impossible not to mention the artistic investigation of Tom Wesselmann, Marina Abramović, Yayoi Kusama, Takashi Murakami, Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons and Fernando Botero, who, on some occasions, have also depicted the naked female body.

Tom Wesselmann

Wesselmann began painting nude women in about 1959, rejecting the prevailing style of abstract expressionism in order to express himself through graphic and provocative portraits. The latter, perfectly suited to the sexual revolution of the 1960s, often lie in suggestive and sensual poses, in which, at times, there is no lack of a semblance of irony. His figures, many of which are modeled after the artist's wife, Claire Selley, often feature vigorous tan lines, having the purpose of drawing the viewer's eye to the focal points of the breasts and pubis. From his first series of nudes, titled "Great American Nude" (1961-73), to his most recent "Sunset Nudes" (2003-04), Wesselmann has dabbled in experimenting with new artistic techniques and compositions, in which unconventional close-ups of the body stand out, having the purpose of generating new ways of teasing viewers with the female form. In summary, in order to better understand her work, we can directly quote the artist's words, "I do not represent nudes for any sociological, cultural or emotional intention." "The nude, I think, is a good way to be aggressive, figuratively speaking. I want to provoke intense and explosive reactions in the viewers."

Retrospective"Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to the Present". Hong Kong: M+ Museum!

Yayoi Kusama

Over the past 50 years, artists, art historians and theorists have thought a lot about the politics, pain and pleasures of the body and how it relates to identity. Yayoi Kusama's extensive body of work, filled with thought-provoking works, has addressed many of the above topics. Indeed, through her wide range of styles and images, which well render her complicated personality, the artist has investigated the body, mainly through performance art. Such investigation, has also captured the nudity of the artist herself, which, marked by her iconic dots, appears in famous photos from the late 1960s, within which Kusama poses along with her "Accumulation" series.

Roman Rembovsky, In the garden of Eden, 2022. Oil on canvas, 120 x 140 cm.

Roman Rembovsky, In the garden of Eden, 2022. Oil on canvas, 120 x 140 cm.

The immortal appeal of the nude: to be continued...

The nude, like still lifes, landscapes, and portraits, represents an immortal subject in the history of art, with which artists will never cease to be confronted, entering into "competition" with the greatest masters of all time. In this context, the female nude turns out to be a subject of great interest, since, if in antiquity it was men who were most represented, it is known how, starting from the Renaissance, the fairer sex "imposed itself" in this type of depiction. Therefore, the above account does not turn out to be exhaustive, as it may be continuously implemented by future, unprecedented, original, and, probably scandalous, points of view.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli