Portrait by Daniele da Volterra, c. 1545.

Portrait by Daniele da Volterra, c. 1545.

Who was Michelangelo Buonarroti?

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, born on 6th March 1475 and passing away on 18th February 1564, was an Italian artist renowned as a sculptor, painter, architect, and poet during the High Renaissance period. Hailing from the Republic of Florence, his work drew inspiration from classical antiquity and left a profound impact on Western art. Michelangelo's exceptional talents and mastery across various artistic disciplines established him as the quintessential Renaissance man, alongside his elder contemporary and rival, Leonardo da Vinci. Thanks to an extensive collection of surviving correspondence, sketches, and reminiscences, Michelangelo is one of the most extensively documented artists of the 16th century. He was hailed by contemporaneous biographers as the most accomplished artist of his time.

Michelangelo gained fame at an early age, having sculpted two of his most well-known works, the Pietà and David, before reaching the age of thirty. While he did not consider himself a painter, Michelangelo created two highly influential frescoes in the history of Western art: the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, featuring scenes from Genesis, and The Last Judgment on the chapel's altar wall. He also played a pivotal role in the design of the Laurentian Library, which introduced elements of Mannerist architecture. At the age of 71, he took over as the chief architect of St. Peter's Basilica, succeeding Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. Michelangelo modified the original plan and completed the western end and the dome according to his vision after his passing.

Michelangelo holds the distinction of being the first Western artist to have his biography published while still alive. In fact, three biographies were published during his lifetime. Giorgio Vasari, one of the biographers, proclaimed Michelangelo's work to surpass that of any living or deceased artist, describing it as "supreme in not one art alone but in all three."

During his lifetime, Michelangelo was often referred to as "Il Divino" or "the divine one." His contemporaries admired his terribilità, his ability to evoke a sense of awe in viewers through his art. Later artists' attempts to imitate the expressive physicality found in Michelangelo's style contributed to the emergence of Mannerism, a brief artistic movement following the High Renaissance.

Michelangelo, Tondo doni, 1504. Tempera on board. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Key concepts

Michelangelo's initial exploration of classical sculpture coincided with his in-depth examination of human corpses. Through his privileged access to a nearby hospital, he acquired a near-surgical comprehension of human anatomy. As a result, the muscular structure he portrayed in his artworks is incredibly lifelike and meticulously accurate, giving the impression that his figures could come alive at any given moment.

No artist has been able to match Michelangelo's unparalleled skill in transforming an entire sculpture from a single block of marble. He famously expressed, "I saw the angel trapped within the marble and carved until I set him free." Renowned as the sculptor who had the ability to bring life out of stone, his mastery in this art form was unmatched.

Despite identifying himself primarily as a sculptor, Michelangelo defied expectations by creating what is arguably the most renowned fresco in the annals of global art. Depicting episodes from the Old Testament, his magnificent masterpiece, which graces the ceiling of the sacred Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, draws millions of tourists to Rome annually. The endeavor of painting the ceiling stands as a central part of Michelangelo's legend. It chronicles the story of a discontented artist toiling for four years under uncomfortable and confined circumstances on a commission he had no desire for, perched atop scaffolding.

Michelangelo, hailed as one of the most extraordinary artists in history, holds the distinction of being the first to have his biography published while still actively pursuing his craft. The eminent Renaissance biographer, Giorgio Vasari, solidified Michelangelo's exceptional talent through his renowned work, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550).

The artist's renowned and fiery temperament is the stuff of legends. He frequently abandoned projects midway or defiantly expressed himself through provocative methods, such as incorporating his own likeness into figures or including the faces of his adversaries in a mocking manner. One notorious incident involved an attack on a prominent Vatican priest named Biagio de Cesena, who had voiced objections about the explicit nudity depicted in Michelangelo's Last Judgment fresco. Seeking revenge, the artist portrayed Minos, the mythical judge of the dead, with Cesena's face while also adding donkey ears and depicting a serpent biting his genitals.

Early life

Michelangelo was born on 6th March 1475 in Caprese, which is now known as Caprese Michelangelo, a small town located in Valtiberina near Arezzo, Tuscany. His family had a background in banking in Florence for several generations, but their bank failed. Michelangelo's father, Ludovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni, briefly held a government position in Caprese, where Michelangelo was born. During that time, his father served as the town's judicial administrator and podestà of Chiusi della Verna. Michelangelo's mother was Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena. The Buonarroti family claimed to have descended from Countess Matilde di Canossa, although this claim remains unverified, it was believed by Michelangelo.

After a few months, the family returned to Florence, where Michelangelo was raised. When his mother fell seriously ill and passed away in 1481 when he was six years old, Michelangelo lived with a nanny and her husband, who was a stonecutter, in the town of Settignano. His father owned a marble quarry and a small farm in Settignano. It was during his time there that Michelangelo developed his fondness for marble.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Last Judgment, 1536-1541. Fresco, 1370×1200 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Last Judgment, 1536-1541. Fresco, 1370×1200 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Training

During his youth, Michelangelo was sent to Florence to study grammar under the guidance of Humanist Francesco da Urbino. However, he showed little interest in his formal education and instead gravitated towards copying paintings from churches and spending time with fellow painters.

At that time, Florence was the leading center of arts and learning in Italy. Art was supported by the Signoria (town council), merchant guilds, and affluent patrons like the Medici family and their banking associates. Florence witnessed the flourishing of the Renaissance, a period marked by a revival of Classical scholarship and artistic pursuits. In the early 15th century, architect Filippo Brunelleschi, after studying ancient Roman buildings in Rome, constructed two churches—San Lorenzo and Santo Spirito—that exemplified Classical principles. Sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti dedicated fifty years to creating the bronze doors of the Baptistry, which Michelangelo later referred to as "The Gates of Paradise." The exterior niches of the Church of Orsanmichele showcased works by renowned Florentine sculptors such as Donatello, Ghiberti, Andrea del Verrocchio, and Nanni di Banco. The interiors of older churches were adorned with frescoes, predominantly in the Late Medieval and Early Renaissance styles. These frescoes were initiated by Giotto and continued by Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel, both of whom Michelangelo studied and replicated through his drawings.

During Michelangelo's childhood, a group of painters from Florence was summoned to the Vatican to decorate the walls of the Sistine Chapel. Among them was Domenico Ghirlandaio, a prominent artist skilled in fresco painting, perspective, figure drawing, and portraiture. Ghirlandaio, who operated the largest workshop in Florence, took on Michelangelo as an apprentice in 1488 when he was just 13 years old. The following year, Michelangelo's father convinced Ghirlandaio to pay him as an artist—an unusual practice for someone of his age. In 1489, when Lorenzo de' Medici, the de facto ruler of Florence, requested Ghirlandaio to send his two most talented students, Michelangelo and Francesco Granacci were chosen.

From 1490 to 1492, Michelangelo attended the Platonic Academy, a Humanist academy established by the Medici family. It was during this time that he was exposed to the influential philosophers and writers of the era, including Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola, and Poliziano. Michelangelo created sculptural reliefs such as the Madonna of the Stairs (1490-1492) and the Battle of the Centaurs (1491-1492), the latter based on a concept suggested by Poliziano and commissioned by Lorenzo de' Medici. He also collaborated with sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni for a period. At the age of seventeen, Michelangelo encountered an altercation with another student, Pietro Torrigiano, who struck him on the nose, resulting in the disfigurement that is noticeable in his portraits.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Libyan Sibyl, c. 1512. Fresco, 395×380 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Libyan Sibyl, c. 1512. Fresco, 395×380 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Early works

In 1494, as Florence faced the threat of a French siege, Michelangelo, concerned for his safety, relocated to the safer city of Bologna after a brief stop in Venice. There, he became friends with the wealthy senator Giovan Francesco Aldrovandi, who secured a commission for the 19-year-old Michelangelo to complete the remaining statuettes for the marble sarcophagus lid for the Arca of St. Dominic. The original lid, created by Niccolò dell'Arca, had been installed in 1473, and Michelangelo sculpted additional figures, including Saint Proculus, Saint Petronio, and an angel with a candelabra, in 1496. At just 19 years old, Michelangelo's attention to detail in the folds of the cloth and drapery, as well as his portrayal of Petronio in mid-step, outshone the work of the older sculptor.

Michelangelo briefly returned to Florence after the French invasion threat diminished. During this time, he worked on two statues: one of St. John the Baptist and a small cupid. The cupid sculpture was sold to Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio, who believed it to be an antique. Although angered upon discovering the deception, Cardinal Riario admired Michelangelo's talent and invited him to Rome for a new project. Michelangelo created a statue of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, which, upon completion, was rejected by the cardinal due to political considerations regarding the association with a naked pagan figure. Michelangelo, known for his fiery temperament, was furious. Years later, he instructed his biographer, Condivi, to deny that the commission came from the cardinal and instead attribute it to his banker, Jacopo Galli, who had acquired the finished work.

Michelangelo remained in Rome after completing the Bacchus sculpture, and in 1497, Cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas, the French Ambassador to the Holy See, commissioned him to create a Pietà for the chapel of the King of France in St. Peter's Basilica. Although the Pietà was not part of the biblical narrative of the Crucifixion, it was a common subject in devotional works, aiming to inspire repentant prayer. Michelangelo's Pietà was distinct as he sculpted two figures from a single block of marble. His portrayal, characterized by emotional depth and realism, garnered widespread acclaim and admiration. The Pietà became one of Michelangelo's most renowned early sculptures, with the 16th-century biographer Giorgio Vasari describing it as something that "nature is scarcely able to create in the flesh."

Despite solidifying his status as one of the period's most extraordinarily gifted artists, Michelangelo did not receive major commissions for about two years. Financial concerns, however, were not his primary focus. As he later remarked to Condivi, "However rich I may have been, I have always lived like a poor man."

In 1497, the monk Girolamo Savonarola gained notoriety in Florence with his Bonfire of the Vanities, an event where art and books were publicly burned. This disrupted the thriving Renaissance culture of the city. Michelangelo had to wait until Savonarola's removal a year later before returning to Florence.

In 1501, Michelangelo embarked on his most monumental sculpture project, which he completed in 1504. The Wool Guild commissioned him to finish a project that had been started by Agostino di Duccio nearly 40 years earlier. The project involved creating a 17-foot-tall nude statue of the biblical hero David. The finished sculpture, recognized for its historical significance in the realm of sculpture, akin to Leonardo's Mona Lisa in painting

Regarding the David sculpture, art historian Creighton E. Gilbert described it as the ultimate representation of the Renaissance ideal of perfect humanity. Originally intended for the cathedral buttress, its grandeur convinced Michelangelo's contemporaries to place it in a more prominent location, which was determined by a commission consisting of artists and notable citizens. They decided to install the David in front of the entrance of the Palazzo dei Priori (now known as Palazzo Vecchio) as a symbol of the Florentine Republic.

Following the completion of David, Michelangelo received various painting commissions. One surviving painting is the Doni Tondo (The Holy Family) created in 1504. Gilbert notes that this artwork demonstrates the artist's fascination with the work of Leonardo da Vinci. Although Michelangelo consistently denied being influenced by anyone, scholars generally agree that Leonardo's return to Florence in 1500 after a long absence had an impact on younger artists, including Michelangelo.

During the High Renaissance in Florence, there was intense rivalry among artists vying for important commissions and recognition. Leonardo, being 23 years older than Michelangelo, was the most celebrated figure among the Renaissance masters in Florence. However, there was an unspoken rivalry between the two. In 1503, Piero Soderini, the lifetime Gonfalonier of Justice, commissioned both artists to paint opposing walls in the Salone dei Cinquecento of the Palazzo Vecchio. This event created great anticipation as Florence eagerly followed the progress of their preparations. Unfortunately, Soderini abandoned the project, and neither Leonardo's The Battle of Anghiari nor Michelangelo's The Battle of Cascina were ever completed. Leonardo returned to Milan, while Michelangelo was summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II.

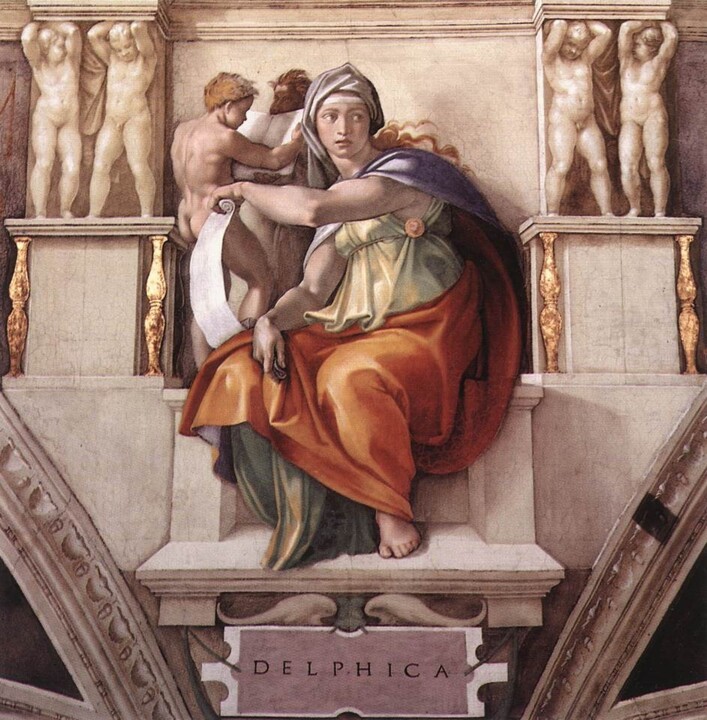

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Delphic Sibyl, c. 1508-10. Fresco, 350×380 cm . Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Delphic Sibyl, c. 1508-10. Fresco, 350×380 cm . Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Mature Period

In Rome, Michelangelo began preparing for the construction of the Pope's tomb, a massive mausoleum that was supposed to be completed within five years. He traveled to the renowned quarries in Carrara, spending around six months meticulously selecting the perfect blocks of marble for his sculptures. However, to his dismay, Julius II summoned him back to Rome and informed him that the designated building for the tomb would be demolished, putting the entire project on hold. Michelangelo was furious and became convinced that there was a conspiracy to ruin him. He even believed that Bramante, the architect of the new St. Peter's Basilica, was plotting to have him poisoned. Filled with anger, Michelangelo returned to Florence and wrote a letter expressing his disgust at the way he had been treated in Rome.

Michelangelo found himself in the midst of a delicate diplomatic situation between Florence and Rome. As Gombrich explains, the leader of Florence persuaded Michelangelo to return to the service of Julius II and provided him with a recommendation letter stating that his artistic abilities were unparalleled throughout Italy, and even the world. It emphasized that with kindness, Michelangelo could achieve astonishing feats that would leave the world in awe.

After creating a colossal bronze statue of the pope for the recently conquered city of Bologna (which was later dismantled after the papal occupiers were expelled), Michelangelo was commissioned by Julius II to continue a project that had already been started by Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and others. This new commission involved painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Legend has it that Bramante convinced the Pope that Michelangelo was the best candidate for the job, knowing that Michelangelo was primarily known for his sculptures and was unlikely to succeed in such a monumental painting endeavor.

Michelangelo dedicated nearly four years to working on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. It was an immensely challenging task, with the artist painting the ceiling while lying on his back atop a wooden scaffold structure (made even more difficult because he had dismissed all but one of his assistants, who helped with paint mixing). The result was a monumental work of astonishing virtuosity, depicting stories from the Old Testament such as the Creation of the World and Noah and the Flood. The finished masterpiece, featuring several nude figures (a rarity for that time), became an awe-inspiring testament to human creativity.

A young and ambitious rival to Michelangelo emerged in the form of Raphael, who burst onto the art scene at the age of 26. In 1508, Raphael was chosen to paint a fresco in Pope Julius II's private library, a prestigious commission that Michelangelo and Leonardo also coveted. As Leonardo's health declined, Raphael stepped into the role of Michelangelo's greatest rival. Known for his skill in depicting anatomy and his finesse in painting nudes, Raphael faced accusations from Michelangelo of copying his work. While Raphael acknowledged some influence from Michelangelo, he resented the animosity and responded by portraying Michelangelo with a sulking expression in the guise of Heraclitus in his renowned fresco, The School of Athens (1509-11).

After completing the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Michelangelo returned to his earlier project for the tomb of Pope Julius. Between 1513 and 1515, he carved Moses, a sculpture that displayed a new level of detail and control influenced by the figures of the prophets he painted on the Sistine ceiling. Additionally, he sculpted two more figures, believed to represent slaves or prisoners, originally intended for the Julius tomb project. These sculptures remained in Michelangelo's possession until his old age, when he gifted them to a family who had cared for him during a previous illness. Today, they are housed in the Louvre Museum.

Following Pope Julius II's death in 1513, the funding for his tomb was reduced. Michelangelo was then commissioned by the new Pope Leo X to work on the façade of the Basilica San Lorenzo, the largest church in Florence. Unlike the previous basilicas dedicated to the papacy, San Lorenzo honored the legacy of the Medici family. Michelangelo spent the next three years working on the project, but it was eventually canceled due to insufficient funds. During this time, Florence was under the rule of Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, who was Pope Leo X's cousin. Michelangelo developed a close working relationship with the Cardinal and enjoyed creative freedom under his patronage. Although a planned project for a parish church in San Lorenzo never materialized, Michelangelo did work on the design for The Medici Chapel.

Between 1520 and 1534, Michelangelo focused on the New Sacristy, which complemented Brunelleschi's Old Sacristy on the opposite side of the church. The Medici Chapels describe how Michelangelo worked on the sculptures of the sarcophagi, although only the statues of the Dukes Lorenzo and Giuliano, the allegorical figures of Dawn and Dusk, Night and Day, and the group of Madonna and Child placed above the sarcophagus of the two "magnifici" were completed by him. The execution of the statues of Saints Cosmas and Damian, which flanked the group, was carried out by Montorsoli and Baccio di Montelupo, who were pupils of Michelangelo.

Many consider the sculpture of Night to be one of Michelangelo's most exceptional creations. In his account of Michelangelo's life in "The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects" (1550), Giorgio Vasari includes an epigram by Giovanni Strozzi that praises the figure:

"Night, whom you see sleeping in such sweet attitudes, was carved in this stone by an Angel. And although she sleeps, she has life: wake her, if you don't believe it, and she will speak to you."

The Laurentian Library, known as Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, was constructed within a cloister of the Basilica of San Lorenzo. This library houses a collection of manuscripts and early printed books donated by Cosimo the Elder and Lorenzo the Magnificent. Pope Clement VII commissioned Michelangelo to design the architecture of the library in 1524. Often overlooked in discussions of Michelangelo's works, the library's stairwell (ricetto) showcases his original wall and floor decorations. The columns in the library's main chamber are concealed behind the walls, a departure from the typical placement in classical architectural design. This arrangement allows for the desks to be arranged in rhythmic harmony with the windows. The library is considered an early example of the decorative Mannerist style that emerged during the High Renaissance period.

After Rome was captured and looted by Charles V's armies in 1527, Florence declared itself a republic. However, the city was besieged in October 1529 and ultimately fell in August 1530. In a new agreement between Pope Clement VII and Charles V, the Medici family was restored to power in Florence. Michelangelo, who had worked on fortifications to defend the city (likely out of his love for Florence rather than a strong religious or political conviction), was rehired by Pope Clement. He was given a new contract to resume work on the tomb of Pope Julius II.

In 1534, Michelangelo moved to Rome, where he would spend the rest of his life. He corresponded with his family from Rome, often discussing matters such as his nephew's marriage and the preservation of the family name. With the recent passing of his father and brother, Michelangelo's letters reveal his growing concern about his own mortality.

At the age of 57, Michelangelo formed the first of three close friendships. Tommaso dei Cavalieri, a 23-year-old Italian nobleman, is believed to have been Michelangelo's young lover and lifelong friend. However, some historians, including Gilbert, argue that Michelangelo's sexuality cannot be definitively confirmed. The fact that he had no biological heir suggests that he may have sought an adopted son in Tommaso, whom the artist once described as the "light of our century, paragon of all the world." The belief that Michelangelo was homosexual gains support from his extensive collection of over 300 poems and 75 sonnets, some of which contain homoerotic themes. These poems were published posthumously in 1623, with altered gender pronouns to disguise their original context.

In Rome, Michelangelo returned to fresco painting under the patronage of Pope Paul III. In 1534, he embarked on one of his greatest achievements, creating a grand and dynamic salvation narrative on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. It took him seven years to complete this monumental work known as The Last Judgment, which depicted the theme of Jesus's "second coming." The fresco was part of the broader narrative of Roman Catholic teaching and served as a response to the Protestant Reformation, also known as the Counter-Reformation or Catholic Reformation. This religious movement was spreading across Northern Europe, challenging the authority of the Catholic Church. While adhering to the traditional biblical story, Michelangelo took subtle liberties, such as portraying a beardless Christ and omitting his throne and the winged angels typically associated with the scene.

During this period, around 1537, Michelangelo obtained official Roman citizenship and formed a close bond with Vittoria Colonna, the Marquise of Pescara and a widow. Both Michelangelo and Colonna were poets, and a significant portion of Michelangelo's poetry was dedicated to her. His admiration for Colonna persisted until her death in 1547. He also presented her with paintings and drawings, including the remarkable black chalk drawing known as the Pietà for Vittoria Colonna, created in 1546. Colonna was the sole woman who played a significant role in Michelangelo's life, as his mother had passed away when he was a young child. Their relationship is generally considered to have been platonic.

However, in 1540, Michelangelo encountered Cecchino dei Bracci, the 12-year-old son of a wealthy Florentine banker, while at the Court of Pope Paul III. The epitaphs composed by Michelangelo after Cecchino's death four years later strongly imply a sexual relationship between them. In one of the epitaphs, the artist wrote, "You can still testify how gracious I was in bed, how he embraced me, and in what the soul lives."

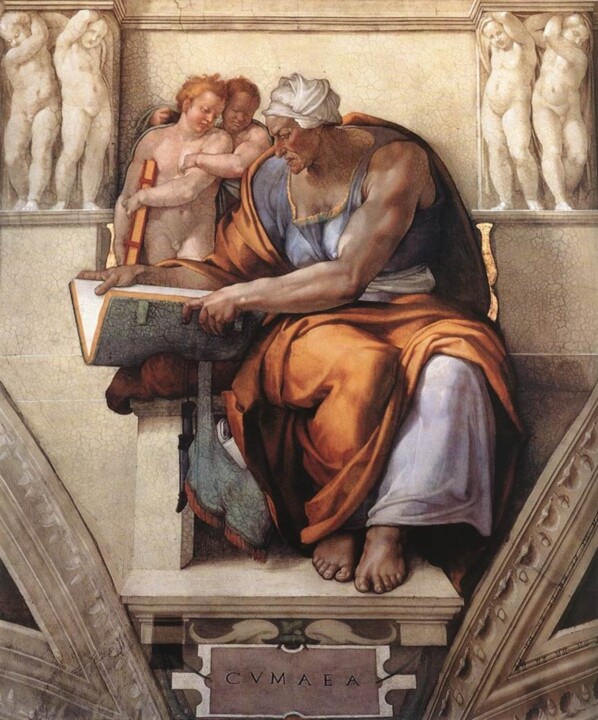

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Cumaean Sibyl, c. 1511. Fresco, 375×380 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Cumaean Sibyl, c. 1511. Fresco, 375×380 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Late Period

During the later phase of his career, Michelangelo increasingly focused on architectural projects. These ventures encompassed various designs, such as the plans for the civic center plaza at Capitoline Hill (in collaboration with Luigi Vanvitelli), the construction of the Church of Santa Maria degli Angeli (initiated in 1562), and the Sforza Chapel within the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore (1561-64). However, his most renowned undertaking was the St. Peter's Basilica, for which he is predominantly remembered.

It was Pope Julius II who proposed the demolition of the old Basilica and the construction of what he envisioned as the "grandest building in Christendom." Although Donato Bramante's design had been chosen in 1505 and foundations were laid the following year, progress had been limited. When Michelangelo reluctantly assumed control of the project from his rival Bramante in 1546, he was already in his seventies. He stated, "I undertake this only for the love of God and in honor of the Apostle."

Michelangelo served as the Head Architect of the Basilica for the remainder of his life. His most significant personal contribution to the endeavor was his involvement in designing the dome located at the eastern end of the Basilica. He disregarded the ideas proposed by previous architects, except for those originating from Bramante's original concepts. Both Michelangelo and Bramante envisioned a structure that would surpass even Florence's renowned dome by Brunelleschi. Although the completion of the dome occurred after Michelangelo's death, the foundation on which it would be constructed was finished, preserving the essence of Michelangelo's majestic vision. As the largest church in the world, the dome stands as a prominent Roman landmark, representing more than a functional covering for the interior of the building—it serves as a testament to Michelangelo's enduring connection to the city.

Between 1542 and 1550, Michelangelo created his final series of frescoes for the private Pauline Chapel in the Vatican. Among these paintings, The Crucifixion of St. Peter includes a horseman wearing a turban, believed by restorers and historians to be a self-portrait of the artist. Although he continued to engage in sculpting, Michelangelo pursued it privately for personal enjoyment. He completed several Pietà sculptures, including the Disposition, which he attempted to destroy, as well as his last work, the Rondanini Pietà, on which he labored until the final weeks before his death.

Michelangelo's fame during his lifetime resulted in a more comprehensive documentation of his career than that of any previous artist, as noted by Gilbert. He became the subject of two significant biographies, marking the first occurrence for a living artist. In Vasari's final chapter of his series on artists' lives (1550), Michelangelo's works were explicitly presented as the pinnacle of artistic perfection, surpassing the achievements of all who came before him. However, Gilbert explains that Michelangelo was not entirely satisfied with Vasari's account and arranged for his assistant, Ascanio Condivi, to write a separate and concise book in 1553, likely based on the artist's own spoken comments. Nevertheless, it is Vasari's lively writing and the influence of his book, translated into numerous languages, that have made it the most prevalent source shaping popular perceptions of Michelangelo and other Renaissance artists.

Gombrich highlights that in his final years, Michelangelo seemed to retreat further into himself. His written poems reveal doubts about whether his art was sinful, while his letters indicate that as his reputation grew, he became increasingly difficult and embittered. His temper, which was both admired and feared, spared no one, regardless of their social status. Michelangelo's highly secretive and guarded nature, coupled with an incident where he mistakenly threw wooden planks at an approaching Pope, whom he believed to be a spy, suggests a struggle with feelings of paranoia. His close companion Tommaso remained with him until his death at the age of 88, following a brief illness at his home in Rome in 1564. In accordance with his wishes, his body was returned to his beloved Florence and laid to rest at the Basilica di Santa Croce.

Michelangelo Buonaorroti, The Creation of Adam, 1508-12. Fresco, 280×570 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo Buonaorroti, The Creation of Adam, 1508-12. Fresco, 280×570 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Top 3 artworks

The Creation of Adam (1508-12)

The Creation of Adam, an artwork by Michelangelo, is a fresco painting located on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Created between approximately 1508 and 1512, it depicts the biblical account of the creation of Adam, the first man, as described in the Book of Genesis. The painting is part of a larger composition with a series of panels illustrating various episodes from Genesis, and it occupies the fourth position in the chronological sequence.

The iconic image of the Creation of Adam has been widely reproduced in numerous imitations and parodies. It remains one of the most replicated and recognized religious paintings in history.

Michelangelo, David, c. 1501-1504. Marble sculpture, 517 cm × 199 cm. Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, Italy.

Michelangelo, David, c. 1501-1504. Marble sculpture, 517 cm × 199 cm. Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, Italy.

David (1501-04)

David, a renowned sculpture of the Renaissance period, was crafted by Italian artist Michelangelo between 1501 and 1504. Standing at an impressive height of 5.17 meters (17 ft 0 in), the statue of David holds significant historical importance as it was the first colossal marble sculpture created since antiquity, setting a precedent for artistic works in the 16th century and beyond. Originally, David was commissioned as part of a series of statues representing prophets to be placed along the roofline of Florence Cathedral's east end. However, it was ultimately positioned in the public square in front of the Palazzo della Signoria, the seat of civic government in Florence. The unveiling of the statue took place on 8 September 1504.

In 1873, the statue was relocated to the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence, while a replica took its place at the original location in 1910. The biblical figure of David held significant meaning in the art of Florence. Due to its representation, the statue became a symbol of the defense of civil liberties embodied in the Republic of Florence. The independent city-state faced constant threats from more powerful rival states and the influential Medici family, making David an iconic emblem of resilience and freedom.

Michelangelo, Pietà, 1498-99. White Carrara marble, 174×195×69 cm. St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican, Vatican City.

Michelangelo, Pietà, 1498-99. White Carrara marble, 174×195×69 cm. St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican, Vatican City.

Pietà (1498-99)

The Madonna della Pietà, also known as La Pietà, is a sorrowful depiction of Jesus and Mary at Mount Golgotha, representing the "Sixth Sorrow" of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This significant work of Italian Renaissance sculpture was carved by Michelangelo Buonarroti between 1498 and 1499. It currently resides in Saint Peter's Basilica in Vatican City and holds a special place among several similar artworks by the Florentine artist.

Originally commissioned for Cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas, a French ambassador in Rome, the statue was intended for the cardinal's funeral monument. However, it was later moved to its present location in the first chapel on the north side after the basilica's entrance during the 18th century. Notably, it is the only artwork signed by Michelangelo himself.

The sculpture captures the poignant moment when Jesus, taken down from the cross, is placed in the arms of his mother Mary. Mary appears youthful compared to Jesus, possibly inspired by a passage from Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy: "O virgin mother, daughter of your Son...your merit so ennobled human nature that its divine Creator did not hesitate to become your creature" (Paradiso, Canto XXXIII). Michelangelo's interpretation of the Pietà is unparalleled in Italian sculpture, skillfully blending classical beauty with naturalism.

Summary

Michelangelo is widely recognized as one of the most exceptional artists in the history of art. His extraordinary talent as a sculptor, painter, and architect is accompanied by a reputation for being passionate and unpredictable. While he played a significant role in the revival of ancient Greek and Roman art, his influence on Renaissance art and culture surpassed mere imitation of the past. In fact, he created sculptures and paintings that were imbued with such profound psychological depth and lifelike emotions that they established a new standard of excellence. Michelangelo's most significant works, including the monumental painting of biblical stories on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, the impeccably crafted and towering statue of David, and the profoundly moving Pietà, are regarded as some of the greatest accomplishments in human history. Visitors from all over the world travel to Rome and Florence to witness these masterpieces in person.

The Legacy

Michelangelo's exceptional skill in sculpting the human figure was unparalleled. His mastery of technique was so extraordinary that his marble creations appeared to come to life as if they were living beings with flesh and bones. His ability to convey human emotions and delve into psychological depths further elevated his reputation and brought him immense fame during his lifetime. Alongside his renowned works such as the Pietas, David, and Moses, he adorned the Vatican City's Sistine Chapel with the most famous ceiling fresco in the world, turning it into a place of pilgrimage for people of various faiths and backgrounds. Gombrich described Michelangelo's cupola for St. Peter's Basilica as a monumental testament to the spirit of this remarkable artist, with its majestic outline rising above the city of Rome and appearing to be supported by a ring of twin columns.

The impact of Michelangelo's art can be traced in the works of esteemed figures like Raphael, Peter Paul Rubens, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and even the last great realist sculptor in his tradition, Auguste Rodin. However, as Gilbert suggests, Michelangelo belongs to a select group of artists that includes William Shakespeare and Ludwig van Beethoven. These artists have delved into the profound and universal aspects of the human experience, but their influence on later art has been relatively limited due to the immense grandeur and cosmic quality present in their works. Their achievements set a high standard that subsequent artists found challenging to emulate.

In a recent interview, singer-songwriter Bob Dylan drew a parallel between his songwriting process and Michelangelo's approach. He referenced a song called "Chip Away" by Duff McKagan, noting its significance for him. Dylan compared the process of chipping away at solid marble stone to discover the form of King David to his own method of songwriting. He explained that he would overwrite his compositions and then gradually refine them by chipping away lines and phrases until he arrived at the essence of the song, similar to how Michelangelo revealed the true form of his sculptures by removing excess material.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli