The first problem I have in considering the hazel (apart from the minor detail that, in the last few days when I have been confined to bed/the house, it has been bright and sunny – ideal photographic weather – and now that I’m able to wobble into the garden to take pics, it’s dull and pouring) is that I don’t know whether my hazel is in fact a hazel or a cob. The second problem is that I don’t know whether the hazel/cob is a bush or a tree. The third problem is squirrels …

The first problem I have in considering the hazel (apart from the minor detail that, in the last few days when I have been confined to bed/the house, it has been bright and sunny – ideal photographic weather – and now that I’m able to wobble into the garden to take pics, it’s dull and pouring) is that I don’t know whether my hazel is in fact a hazel or a cob. The second problem is that I don’t know whether the hazel/cob is a bush or a tree. The third problem is squirrels …

I did some investigating into hazels about eighteen months ago, after our visit to the site of the Curtain Theatre in Shoreditch, and since then I have done more. It’s almost certain that I have a common hazel (Corylus avellana) rather than a cob or filbert (C. maxima), but the most important way for amateurs to spot the difference is that the cob has an elongated tubal involucre (i.e. the husk which surrounds the nutshell completely envelopes it), whereas it’s much shorter in the common hazel. However, because of Problem 3, I don’t usually get to see fully grown nuts inside the husk.

Looking up through the canopy.

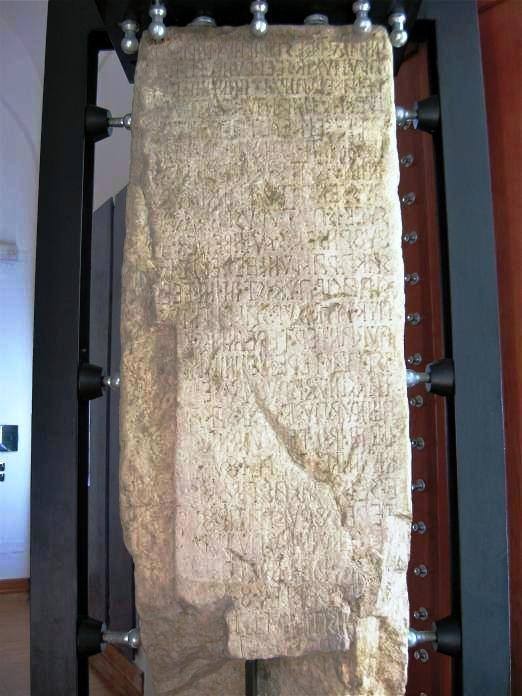

The genus Corylus was named by Linnaeus, and there are somewhere between 14 and 18 species (the East Asian ones being points of taxonomic dissension). The specific name is interesting: Avella was/is the Samnite and later Roman town of Abella in Campania, at the ‘back’ of (i.e. further inland than) Vesuvius, but served by a branch of the Circumvesuvio railway. The Latin name rang faint bells – and lo, it is the home town of the Cippus Abellanus, a most important inscription (because lengthy) in Oscan, discovered in 1745 and reused as a house threshold; it was later rescued and now resides in the seminary in Nola. The text (of the late second century BCE) describes the ambit and possessions of a sanctuary of Hercules situated on the boundary between Nola and Abella.

One face of the Cippus Abellanus.

More relevantly in this context, Abella is name-checked by Vergil (Aeneid VII. 740) among the Italic towns who sent troops to support Turnus against the invading Trojans: et quos maliferae despectant moenia Abellae. ‘Apple-bearing’ is an interesting epithet: later writers confirmed that the area was rich in fruit trees (rather than arable crops) and nuces avellanae were apparently choice nuts. (It plainly spread: ‘hazel nut’ in Spanish is avellana, and in Romanian alună; though cf. Italian nocciola and French noisette.)

The German physician and botanist Leonhart Fuchs (1501–66), in his magnificent, illustrated 1542 De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes, gives the Haselnuss the name ‘Avellana’, and this was adopted by Linnaeus.

A portrait of Fuchs (1541) by Heinrich Füllmaurer, one of the artists who illustrated his great work.

Fuchs’ description of the plant (above), and the full-page engraving (below).

As more Corylus species were discovered, the specifics became (perhaps) predictable: going west, Corylus americana; but eastward, C. colchica, chinensis, yunnanensis, sieboldiana, fargesii, jacquemontii – the last three tributes to well known plant hunters. The most exotic is C. ferox, which justifies its name by a complex mass of spikes which at first glance resembles the sweet chestnut.

As to whether it’s a tree or a shrub, the answer appears to be that it’s a small tree, with the growth traditionally kept in check by coppicing, which provides a harvest of hazel sticks which can be put to many uses from fencing to spoon-making. I use the prunings for plant stakes and overlooping/overlapping edges for borders, and for the ‘trees’ which support my Christmas stall offerings,

Hazel cuttings put to charitable use.

but I haven’t yet tried anything more adventurous like making hoops for garlands – perhaps this year? But the other thing that, increasingly, the hazel is being used for is as a measure of climate change.

I wasn’t aware until too late that the Woodland Trust was holding a survey of earliest hazel flowering – and of course it depends what you mean by flowering: the catkins form in autumn, but presumably the actual flowering is defined as the point at which the males open up to release their pollen and become like the proverbial lambs tails.

The catkins, forming before the last yellow leaves have dropped in autumn.

The earliest reported flowering on their website is 27 October in Southampton, while the first of mine were open in mid-December (I’ll note the exact date next time!). It’s certainly getting earlier by comparison with 60-odd years ago, when we went in February or even March to collect lamb’s tails and pussy-willow (oh, the innocence!) for the nature table at my primary school from our local bomb-sites.

The open male catkins (the females are tiny and insignificant-looking). (This picture was taken when it was merely dull this morning, before it started snowing …)

Hazel and willow (Salix caprea) are both brilliant colonisers: the latter by the drifting seed that wafts up and around from the river every spring, the former usually through the intervention of Problem 3: the ones the squirrels don’t eat on the spot (leaving the shells lying around to mock me) they take away and bury for later.

Either unripe or already enjoyed …

If I leave pots of spring bulbs unprotected by wire netting, they are invariably disturbed not only by various foraging rodents but also by the squirrels looking for nice soft earth for their plunder.

I ran out of wire mesh, so the future is anything but bright for these ‘Pink Diamond’ tulips …

I quite often find walnuts as well as hazelnuts secreted, though I have no idea where the nearest walnut tree is. I wonder whether, now that grey squirrels seem not to hibernate at all, coming to feast daily on my bird-feeders, the incentive to bury stocks of food for their occasional wakings will be bred out of them?

My own hazel is completely adventitious: like much else in my garden, I let it grow for a bit, and then a bit longer, and twenty years on, here we still are … I have done nothing except hack it back a bit when it’s actively impeding my neighbour’s path, or when I need twigs, but it split into four trunks at the base very early on.

Is quatrofurcation a word? (Some small suckers await the snip.)

It is very well behaved, and barely suckers at all, unlike the C. avellana contorta which I – fool that I was – deliberately planted in the back garden, and which rapidly grew to enormous size, produced virtually no catkins, and threw suckers up all over the place. It had to go – I have enough problems with next door’s plum tree, which is glorious in blossom for one week every year, and for the rest of the summer drips honeydew from the endemic whitefly, and then half-rotten plums (unharvestable because the tree is so tall), all over my garden and into my pond, while it suckers as though its life (or the survival of its species) depends on it.

Hazel leaves in summer.

But my common European hazel provides catkins in winter/spring, bright green leaves in summer, which then melt to glorious butter yellow in autumn, and year-round shelter for the birds – nothing not to like, except that, one day, I really hope to taste a nut.

Caroline

Missing link? You write you didn’t investigate hazels until after your visit to the Curtain Theatre in Shoreditch…to see an archaelogical site filled with self-seeded hazels? to see a play abut hazels? to pay a visit to the cob society currently resident on site there? Interesting connection but lost in process of editing? Do explain, even of at the expense of privacy….

LikeLike

That’s odd, I can see the link, and it works – but it’s to an earlier blog: https://professorhedgehogsjournal.wordpress.com/2016/07/04/hazelnuts/

Hope this helps!

LikeLike