Interview by Eric Hsu

Photography by Helen O’Donnell (unless otherwise noted)

I first became aware of Helen O’Donnell through her blog(www.anemonetimes.blogspot.com) where I had enjoyed reading about her gardening adventures in New England and abroad. I finally got to meet her briefly in person when she came down to volunteer at Chanticleer a few years ago, and had fun seeing gardens with her during my summer holiday in Maine last August. Helen is passionate about plants and gardens, having worked in some of the most beautiful New England gardens as a designer and horticulturist. She has taken her skills to another level as a deft propagator of annuals, tender perennials, and perennials at Bunker Farm, Dummerston, Vermont. The farm’s site can be visited at http://thebunkerfarm.com/.

Please introduce yourself.

I am a gardener, garden designer, printmaker, and co-owner of The Bunker Farm where I run a specialty annual and perennial nursery in southern Vermont.

The arts or the garden?

Both! I have worked as a gardener and farmer every season since I was 15 and I studied art in college and spent a year in Florence, Italy studying printmaking. And I have spent different amounts of time working in both fields, teaching printmaking at the Putney School and simultaneously working as a gardener and garden designer. As my art is completely influenced by plants, landscapes, and the outside world, it is hard to approach gardening, garden and plant design without art. The garden is probably the most complicated form of art, with it encompassing all the dimensions. You have 2-D and 3-D principles of design (color, form, shape, texture, light etc.), but then there is the fourth dimension of time, like music, dance, or theater. There is a performance aspect that follows the seasonal changes, as the plants are growing and changing expectantly and surprisingly. There is an audience participation that is completely out of your control from weather to microbes.

What is your earliest memory of plants or gardening?

I remember my parents sitting down with me after school once, I must have been around 8, and telling me that I wasn’t allowed to eat plants at school. I guess the teachers called home concerned because I was showing all the kids what plants they could eat in the playground. My dad showed me what plants to eat because he was a chef and used to garnish his plates with all sorts of edible flowers. I have really strong memories of foraging around outside for wood sorrel, vetch flowers, violets, and clover and finding them delicious.

You spent the first part of your career working for the landscaping company Deer Meadow in Maine. How did that professional experience shape your present relationship with horticulture?

Working for Deer Meadow taught me three main things, one was that I seemed to have a knack for gardening at age 17, two that I really liked doing physical work, and three, I learned the importance of working and learning under a serious, knowledgeable head gardener. Diana Johnson’s encouragement, enthusiasm, and knowledge about plants and willingness to teach me was inspirational. With the encouragement from my parents, (my mother is a brilliant gardener) I continued to learn under other talented gardeners who all shaped me into who I am now.

The New England region is sometimes overlooked for its gardens especially since the Mid-Atlantic and Pacific Northwest often receives attention. Beautiful gardens are always found despite climatic challenges and New England is no exception. What gardens, private and public, in your region inspire you?

Close to home, there are a few pockets of great gardening here in central New England. Right here in Putney is Gordon and Mary Hayward’s garden, where I worked for years. They have a beautiful garden comprised of English-style garden rooms, complete with hedges, axial views, evergreen pillars, woodland walks, and long borders, yet with the backdrop of New England hayfields, locust trees, and fruit orchards. Over in Peterborough, New Hampshire there is cluster of terrific gardens and gardeners. One is Juniper Hill where Joe Valentine references iconic English gardening ideas against the scenery of a classic New England house and sheep pastures. Michael Gordon’s town garden is built on a steep slope and includes three main terraces, all with highly original plant designs, incorporating self-seeders, with unusual annuals and unique shrub specimens. Maude Odgers of the Artful Gardener has a beautifully romantic garden with sweeping curvy beds filled with an array of specimen plants, in cool color tones, but filled with juxtaposing textures.

Another favorite, and one that not enough people have visited yet, is Bruce Lockhart’s Swift River in Petersham, MA. He truly has it all with meandering woodland full of great swaths of interesting woodland specimens, trees, and shrubs. As well as pleasure gardens, more typical style mixed plantings framed by hedges and paths, plus a magnificent Piet Oudolf-style meadow, with thousands of wild, blooming perennials and grasses. Add a vast rock garden full of unusual alpine and rock specimens, many that he started from seed. It is a fantastic garden and one people must visit.

Great Dixter is often cited as one of your favorite gardens overseas where you have visited and worked several times. Outside of Great Dixter, what other gardens in England and elsewhere do you like? And their strong points?

I spent a month at Hidcote Manor in the Cotswolds before my time at Great Dixter and that was my first glimpse into English gardening. For me, that garden feels mysterious; the garden rooms feel like a maze, each opening revealing a different path to take. There is an immense feeling when standing at the top of the long view, looking down the long avenue of hornbeams. It is a garden where I feel the presence of its creator Lawrence Johnson, much like at Great Dixter, where the spirit of Christopher Lloyd remains, is revered, and is celebrated still. On my last trip to England I visited Charlotte Molesworth’s topiary garden in Kent and I was really touched by that garden. I didn’t get to meet her or her husband, but to me, the garden feel wholly authentic. It was so creative and so expressive, with every evergreen shaped into magnificent birds, spirals, tiers, and minarets. The other thing that really appealed to me is that the garden itself felt completely lived in and the spaces were well used, I loved the seating areas and patios and how the garden went from highly ornamental to practical all at once. I am not sure I have ever been to a garden that felt so completely genuine, that every choice was theirs to make for the love of it.

Gardening is riding a switchback of hope and disappointment once climate adjusts your expectations. How has cold-climate gardening, complemented by mild-climate gardening in UK and elsewhere, characterized your gardening style now?

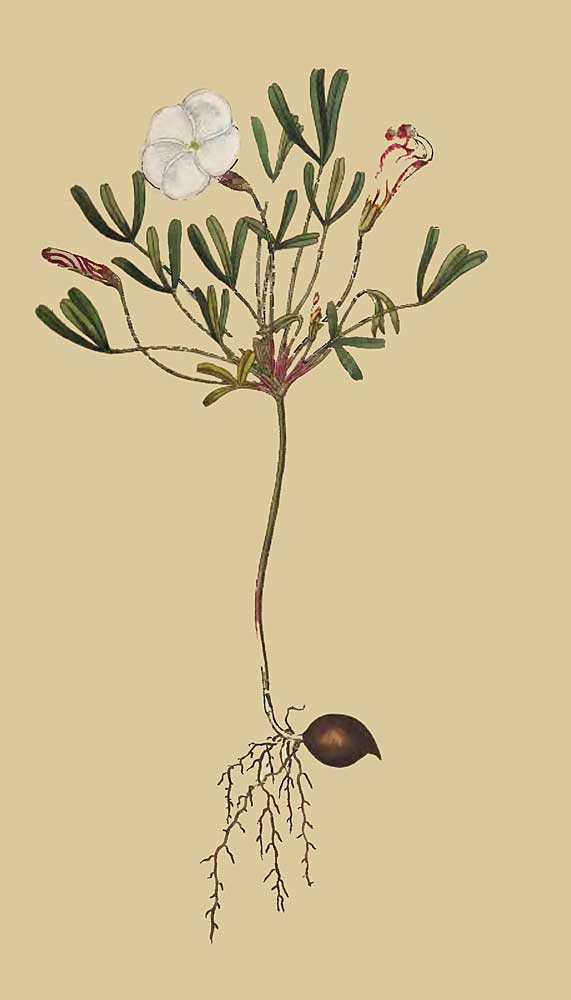

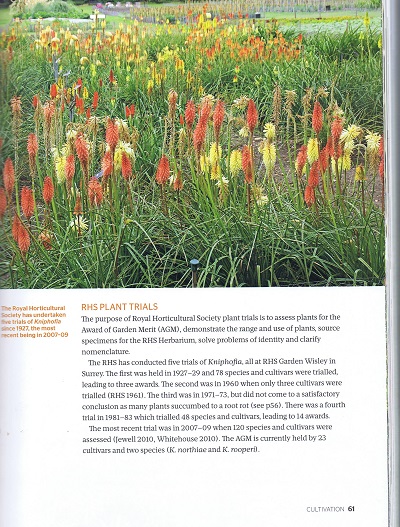

I am an optimist through and through so I really do believe that every climate has its advantages. We know England can grow incredible coveted plants, but we can grow Cleome and Echinacea! I know that sounds boring, but those plants are exciting and can be hard to grow for British gardeners. Of course I am like everyone in that I try and “push” my zone. However, growing and raising plants is more interesting than just sticking to the zone on the plant tag. I understand why most gardeners wouldn’t buy a plant not rated to their zone, but when raising things from seed and really paying attention to what works in your own garden, you can start to get away with all kinds of things. I am always surprising myself with what I can grow (and can’t grow). I have recently been experimenting with a gravel garden where I have never watered or added any compost or fertilizer. The garden is at the top of a stone wall, south facing protected from the north wind by the house, and mulched with gravel- which gives it excellent drainage in winter. I am growing all sorts of stuff that shouldn’t survive here- like Stipa gigantea (hasn’t bloomed yet, but it has survived three winters now), Knifophia caulescens, Hypericum androsaesum ‘Albury Purple, Ferula communis– none of these plants have reached their full potential yet, but they still survive and I find that pretty interesting.

Agriculture is the precursor to horticulture – once the land provided what humans needed to nourish and shelter themselves, it too became a place for ornamental use (i.e. cottage gardens). Once food production became industrialized, humans gradually lose their agricultural roots as they migrated to urban centers. Gardens and farms are different systems because the latter is more inclusive (i.e. animal husbandry and post-harvest processing). Was it a natural step for you to become a farmer while still working in horticulture?

Yes. My first job was working on an organic vegetable farm. I started when I was 15 and after the second summer the farm was given away, I then migrated over to landscaping because I liked working outside and with plants. From then on I just kept gardening. I don’t have a degree in horticulture, but I have had a very rigorous education working for and learning from the best of gardeners, all of it ‘hands on’, learning passed on through the work itself. I just kept doing it because I like it. Farming is the same way. I like raising things and I like working. And if you are paying attention and giving your work a lot of care, then you will get better at it. Whether it is flowers or cows, it feels the same.

The Bunker Farm certainly embodies the small-scale local agricultural ethos that come to define rural communities near urban centers. I understand that the farm’s goal is to be self-sufficient, sustainable, and have strengthening ties to the community. How did your farm come about within your interests?

It definitely felt like a very fortuitous turn of events. My husband Noah and I had been farming on a small scale on his family’s land. We had a few cows and pigs and I had a tiny greenhouse where I grew annuals for gardening clients. My sister and her husband lived across the street and we would raise chickens and garlic together. Noah and I were looking at properties hoping to find something of our own that we could continue to do similar small scale farming. We would constantly look at really run down properties and drag Jen and Mike along and start dreaming about all the things we could do together. Then Noah saw an ad seeking applications to buy the Bunker Farm through the Vermont Land Trust. This proposition was much bigger than any of us could have dreamed about previously. But the land and the buildings offered us all so much and we each had skills to fill each part of the farm. Noah worked on a small dairy farm at the Putney School for 3 years, mastering farm mechanics and cow husbandry and with 60 acres of hay fields, having cows was a natural fit. He knew enough that dairy on a small scale would be difficult, so we went for beef cows. There was born the idea to start a meat CSA, offering pork, chicken and beef. The farm also had 16 acres of old sugar maple woods that could be tapped again to produce maple syrup. Mike had worked for a few years for one of the bigger producers in our area and had the initial skills and passion to start a sugaring operation at the farm. There was a large greenhouse, standing empty, but ready for me to fill it with plants. My sister is a third grade teacher and passionate about outdoor education and works to get school and community groups on the farm. It honestly felt like the land was looking for someone to fill all these different parts, it wouldn’t really work if it was just one thing, and so in the end, the four of us were a good match.

Despite its previous 26-year-old ownership under Larry and Marilyn Cassidy, the farm still needed significant improvements before it could become fully operational. How was funding and the subsequent development approached?

The farm was actually in pretty good shape when we first moved in. The barns and structures were operational, there was power and water everywhere, and the green house was in pretty good shape too. We of course put everything we could into it in the beginning, but we started our first fall with the two cows Noah and I had purchased prior to owning the farm. Each year we have bought more cows in and started our own breeding program and we now have twenty-two cows. In our first year sugaring, we didn’t own an evaporator, which meant we couldn’t even make maple syrup from the sap we collected. Instead we focused on setting up the infrastructure, hanging all the tubing in the woods, and sold the raw sap to a sugar maker down the road. With everything, we started out small and grew each year, acquiring another piece of equipment, upgrading to better systems, etc. We all have other jobs, which took some of the financial pressure off the farm in those busy and expensive start-up years.

James Rebanks, the author of ‘The Shepherd’s Life’ commented in an interview: ‘I like the idea that people lead lives devoted to something bigger than themselves – the landscape, the folks and their continuation. Somebody like my father wouldn’t have thought his life was particularly meaningful or significant in its own right, but he saw himself as part of a community and way of life and tradition. I deeply admire that in an age when most things are about the individual and about instant gratification and consumption.’ What roles do you see yourself and your family within the historical context of Bunker Farm?

I think about this a lot actually because it applies to many different parts of a life. This idea that the four of us belong to something bigger than ourselves has really been a core value of the Bunker Farm. At the micro level, this is how four adults (two being sisters) have survived in a rambling farm house with two toddlers for the past few years, not to mention all of us running a farm business together. You always have to consider the larger purpose, that we are doing something that is more important than our daily needs or comforts. At a more macro level, we definitely feel very humbled to own, work, and live at the Bunker Farm. This is a historic farm and one that has meant so much to so many people in our community- it seems like every neighbor and every neighbors friend knew someone who lived and worked the farm. Not to mention that the farm has meant so much to the Cassidy and the Bunker families. We feel the responsibility to carry the farm forward in a way that our community can feel good about.

Vermont’s winters are long and cold, yet I get a sense that a farmer’s day is rarely quiet. People unfamiliar with farming rhythms tend to view winters as slow months. What would define your responsibilities during winters?

Sugaring season starts in late January these days, so our winters truly are very short. My winter tasks include all the plant and seed ordering, plant lists and database work, garden design work and bookkeeping. Last year I took a nutrient management course that helps our farm write a nutrient management plan (manure, fertilizer, lime applications) for all our hayfields. This program is run through a few different Vermont state organizations, but it is an effort to get small farms to comply with new water quality standards, manure and fertilization regulations. It is in the best interest of the farmers to improve their soil health and soil retention on their farms, so there is an economical benefit for farmers too.

Late January and February brings the seasonal ritual of tapping its astoundingly 3,300 sugar maples for maple syrup, which your brother-in-law Mike Euphrat oversees. Do you participate in the process and how is the syrup different from the others you have tasted?

A sugar bush is measured in number of taps, which is interesting since many large trees can have two taps. We have 1,200 taps on 16 acres here at Bunker Farm and we lease another 3,100 taps on 40 acres down the road from us. In a really, really good season we can make over 2,000 gallons of syrup in a year. I am on the tapping crew, so I go out and help put the taps into the tree, which is essentially drilling a hole in the tree, hammering in a plastic tap, and connecting the tap to a web of tubing that carries the sap to large collection tanks. The season generally runs when the temperatures are above freezing during the day and below freezing at night. This temperature difference gets the sap to move up and down the tree, bringing sweet sap to the emerging buds in the tree. I help check the vacuum in the woods, fixing leaks in the tubing and making sure the taps are tight. We use vacuum pumps to draw the sap through the lines and a reverse osmosis machine that takes sap at its natural 2% sugar solution and pushes it through a filtration system that takes water out and leaves us with a higher sugar concentrate. Boiling, trucking, and canning are all other parts of the operation. In terms of taste, we did win a blind taste test during the Maple Rama festivities last year out of 70 other entries. This win is due to Mike’s fastidiousness in terms of how he runs his operation. He is very clean, very precise, and he measures everything. He finds what works and sticks to it. He is very disciplined and deliberate about the operation, from collection to processing, and he produces a product that really is superior. Most people would think maple syrup is maple syrup but like anything the more you taste and know something, the more you can taste the differences- ours is rich, smooth, clean, balanced, with a slightly wood fired flavor.

February and March coincides with seed sowing and seedling pricking out. It is a crucial junction when lambing and calving season too begins. Given how the demands can be stressful, how do you balance these jobs with your team?

February and March is a really busy time for us with sugaring, it is a really intense season because during a perfect stretch of weather we could be boiling for 24hrs straight with short breaks before you are back at it again. Mike hardly sleeps at all during this time. We plan for pig farrowing end of March and April, but calving isn’t until May and June and we gave up having sheep a few years back. Every season is a little bit crazy, but our worst month is actually May. That is when Noah and Jen are still teaching, my gardening season is in full tilt, the plant nursery is at its peak in sales and watering, Mike is working at Walker Farm, chickens are arriving every two weeks, and pasture rotation is just beginning. Not to mention weeds are growing like mad and the grass needs mowing! We each have our area that we manage but we help each other out as much as we can- during the busy seasons all hands are on deck. It can be really stressful and tiring, but we have a really strong sense of shared purpose that holds us all together.

Propagating and selling annuals is an audacious business move since the everyday gardener rarely moves beyond the ‘bread and butter’ marigolds, pelargoniums, and petunias. A number of the varieties you sell do not necessarily wow upon first impression, although they will impress the jaded gardener later. How do you go about educating your customers that those tufts of foliage forecast tremendous potential?

A lot of people tell me about how hard the nursery business is, it seems like they are always going out of business everywhere. For me, I just started out wanting to grow cool unusual plants that I can’t get anywhere else for my own gardening business and my own garden and from there it has steadily grown. I have about two dozen great gardeners who buy my plants fairly regularly and they are definitely helping to get my name out there, plus existing CSA customers. My plant list seems to attract the type of gardener that doesn’t need the plant to look flashy in order to buy it, which really helps! The other thing I have going for me is my own excitement about what I am growing. Even if I haven’t grown it before, I clearly chose it because it sounded exciting. Gardeners love trying new things and a passionate sales person can help!

Each year, seed and plant catalogs tempt us with endless varieties that either are new color variants, better disease resistance, and later to flower. How do you whittle down your desiderata to realistic limitations of space and time?

That is actually a really interesting question and one that I think about every year. My process is pretty intuitive which sounds a little naïve. I just find myself every year attracted to really different groups of plants each year. For example a few years ago I wanted to grow lots of different perennial Centaureas. It sounds a little boring and they really didn’t sell well, but I fell in love with Centaurea dealbata, C. scabiosifolia, C. ruthenica, and C. macrocephala. The following year it was Dianthus, and I grew some very cool perennial types including D. pinifolius, D. knappii, and D. carthusinorum. Last year I had terrific luck with Mirabilis so I am growing four different cultivars this year. I can imagine over the years I will have a solid list of things I will always grow and then the list of experimentals will come and go and come again. I have a feeling every year will always be different than the last.

What are some of the interesting annuals or tender perennials you have propagated and grown that you envision a bright future?

Here are some solid performers:

- Ageratum houstonianum ‘Red Sea,’ – a really nice bushy mid height Ageratum with a really good purple pink flower.

- Alonsoa meridionalis ‘Rebel’ – shocking orange red in late summer through fall, such a surprise late in the season.

- Ipomoea quamoclit – incredible fine and vining foliage with scarlet tubular star flowers.

- Pennisetum villosum ‘Cream Falls’ – a great floriferous fuzzy flowered grass in bright white. Fills a space and blooms early and long.

- Phlox drummondii ‘Cherry Caramel’ – such a nice surprise last year with its multi colored caramel pink phlox flowers, blooms well with deadheading and for a long period.

- Mirabilis jalapa ‘Limelight’ – one of my favorite annuals, sort of garish, but with incredibly bright chartreuse foliage and hot pink flowers, the plant gets big and bushy and goes all season. Good for a semi-sunny spot.

- Hibiscus acetosella ‘Mahogany Splendor’- grown purely for its foliage in our area, but in one year a single plant can get five feet tall and three feet wide. Leaves resemble a dark red Japanese maple in form, texture and color, though a little larger.

- Tropaeolum peregrinum – a lovely climbing nasturtium vine with bright canary bird flowers. Foliage is so ornate too- nice to let it scramble over and through a dark yew hedge.

In addition, you sell herbaceous perennials to complement the annuals. What are you currently growing?

I am actually growing a fair number to perennials and biennials each year. Some particularly good ones are: Verbascum bombyciferum ‘Polar Summer’, a great biennial verbascum with large rosettes of enormous felty gray leaves. The flower spikes are tall and branching with a semi-snaking habit with bright yellow fuzzy flowers along the stems. Patrinia scabiosifolia is another tried and true and underused perennial around here with upright stems of bright yellow umbel flowers, sweetly scented blooming mid summer. Euphorbia oblongata is another great perennial spurge with lovely striped green leaves and bright yellow flowers, the seed heads look good all season too. Wow, all yellow flowers and all good plants.

What is your desert island plant?

Salvia confertiflora because I don’t think you could feel too lonely next to a plant like that, so big with those large pungent leaves and those long delicate spires covered in fuzzy bright red buds. Plus it would offer some shade on hot days and would bring all the hummingbirds and bees.

What would your advice for those people interested in merging horticultural and agricultural enterprises?

The very unromantic advice I have is to write a really good business plan. We did that (because we were required to in order to buy the farm) and it turned out to be one of the best things we have ever done. We have referenced the plan many times and it helped us prioritize and know where we were headed. It gave us the beginning skills to budget, make financial plans, and work as a group.

Thank you Helen!

You must be logged in to post a comment.