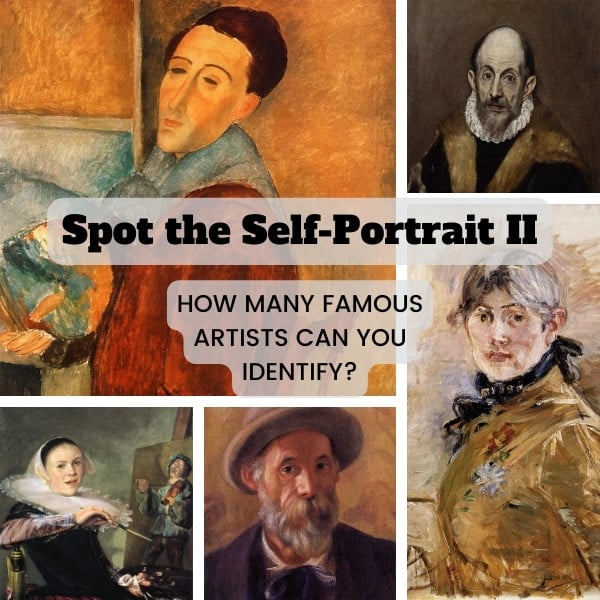

Duccio, “Madonna and Child,” ca. 1300 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

During the Italian Renaissance, a wave of pioneering painters, sculptors, and draftsmen ushered in a golden age of art and culture. While these innovative artists shaped one of history's most important movements, they were far from the first to find artistic success in Italy. Before Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and even Giotto made their marks, Duccio put medieval Italy on the map with his glistening gold panel paintings.

Today, Duccio is regarded as one of the Middle Ages' most groundbreaking artists. Here, we take a look at the life and work of the figure in order to grasp the significance of his artistic contributions—both in Italy and beyond.

Who was Duccio?

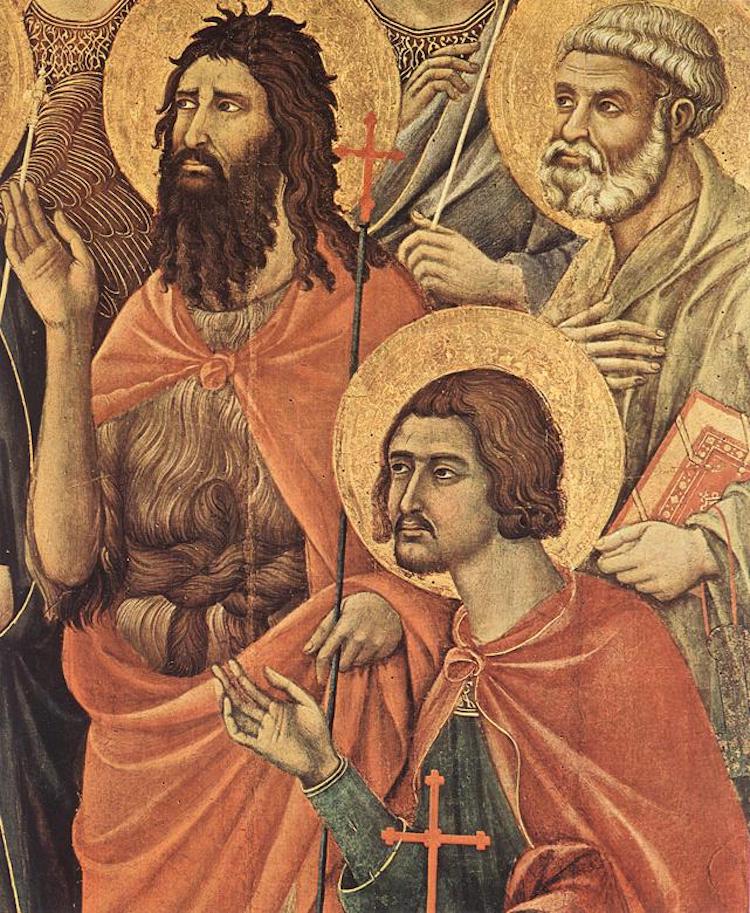

Duccio, “The Calling of the Apostles Peter and Andrew” (detail from the back of the Maestà), 1308-1311 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Duccio di Buoninsegna was born in the Tuscan city of Siena between 1255 and 1260. As expected for an artist living 700 years ago, much of what we know about his life is not confirmed. However, among his contemporaries (even other members of the Sienese School of painting, which he pioneered), his existence was the best-documented, giving us a rare glimpse into life as an artist in Trecento Italy.

The earliest recorded evidence of Duccio's artistic practice is dated 1278. According to documentation that details a payment made by the commune of Siena, Duccio was commissioned to decorate a dozen archival boxes. The following year, he was compensated for another government project: painting book covers. And, after what is believed to have been an extended trip to France, his work is regularly documented from 1285, when he completed the Madonna Rucellai, his first painting on panel.

Duccio, “Madonna Rucellai,” ca. 1285 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Along with other works painted during this time, the Madonna Rucellai demonstrates the influence of Cimabue on Duccio. Cimabue—who famously mentored Giotto, the “Father of the Renaissance”—crafted religious panel paintings adorned with gold leaf. In the 1280s, Duccio adopted this Byzantine-inspired approach, leading historians to believe the pair worked closely—either as collaborators or rivals—during this time.

Cimabue undoubtedly played an important role in Duccio's artistic development. However, particularly in his later years (from around the turn of the century until his death in 1318 or 1319), his style departed from that of Cimabue, culminating in an aesthetic—and a masterpiece—that is distinctively Duccio.

The Maestà Altarpiece

Duccio, “Maestà,” 1308–1311 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Three characteristics have come to define Duccio's style: the use of intricate detail, a delicate treatment of line, and a subtle shift toward humanism. While these elements are present in the majority of Duccio's work, they are most clearly evident in the Maestà altarpiece, Duccio's most well-known work of art.

Duccio completed the Maestà (“Majesty”) in 1308. Intended to adorn the Cathedral of Siena, this double-sided altarpiece comprises several storytelling panels. On the front, it features a monumental central panel portraying the Madonna and Child flanked by angels and saints, including the patrons of Siena. Scenes from the life of the Virgin and the childhood of Christ are respectively found above and below this central panel, while the story of Christ's adulthood are on the back.

While this iconography was prevalent in both Byzantine art (a term that denotes Christian Greek art of the Eastern Roman Empire) and Italian paintings of the time, it is Duccio's distinctive approach that sets the piece apart from others—and, in turn, helps us to understand the characteristics that define his style.

Defining Characteristics

Intricate Details

Duccio, “Maestà” (detail, 1308–1311 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Duccio had a penchant for adding elaborate detail to his paintings. Most often, he rendered these minute intricacies in tempera paint. This is the case for the Maestà, where Duccio's astounding attention to detail can be found in the expressive faces of the saints, the delicate drapery worn by the figures, and, most prominently, the interlace on the monumental, marble throne.

Duccio also adorned his works with details rendered in mediums other than paint. Taking a cue from the Byzantine panel painting tradition, he often ornamented his works with hammered gold leaf, whose sparkle he'd sometimes accentuate with decorative pieces of fabric and even inlaid jewels.

Soft Lines

Duccio, “Maestà” (detail, 1308–1311 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

While Duccio enthusiastically embraced Byzantine gilding, he rejected the practice's tendency toward hard, bold lines. Instead, he used blocks of color to compose sinuous contours and employed modeling—a technique that uses shading and light and dark colors to suggest shapes (particularly beneath drapery). This approach resulted in softer forms and figures, like those featured in the Maestà.

Hints of Humanism

Duccio, “Maestà” (detail, 1308–1311 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Duccio's tendency to soften lines foreshadowed a major shift in Italian art. “During the Middle Ages, Italy maintained political and cultural links with the Byzantine Empire, and Italian art reflected this influence: stylized figures were positioned rigidly against a flat gold ground, their draperies a series of lines,” explains Phaidon's The Art Museum. “At the end of the thirteenth century some masters began to give their figures volume and movement, adding depth to their compositions and introducing emotion and human interaction into the scenes.”

While Duccio is largely considered a Medieval artist, his expressive figures and innovative use of modeling imply an interest toward humanism—a concept that would be at the core of Renaissance art roughly a century later.

Duccio's Legacy

Today, Duccio is widely regarded as the “Father of Sienese painting.” His legacy, however, extends beyond his Italian birthplace. In addition to paving the way for Renaissance artists with his subtle steps toward humanism, he also influenced the Gothic style with his interest in ornamentation and perhaps even inspired Mannerists with his treatment of color and use of sinuous forms.

It is not just Duccio's style that has proliferated over time; his Maestà can now be found all over the world—literally. In 1711, it was dismantled in an attempt to source its pieces and split it into two altarpieces. While many fragments have since been lost, some have made their way into museums across the globe. Whether held by the Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana in Siena, the National Gallery in London, or the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, these panels help piece together the story of one of art history's most important masters.

Related Articles:

Fra Angelico and the Annunciation: How the Ethereal Event Inspired the Early Renaissance Artist

Who Is Titian? Exploring the Life and Art of the Renaissance Master of Color

5 Powerful Paintings by the Under-Appreciated Female Artist Artemisia Gentileschi

Exploring the Extravagance and Drama of Baroque Art and Architecture