The Hours of Queen Claude de France Summary

The Hours of Claude of France is a unique gem of book art between Renaissance and Mannerism.

4

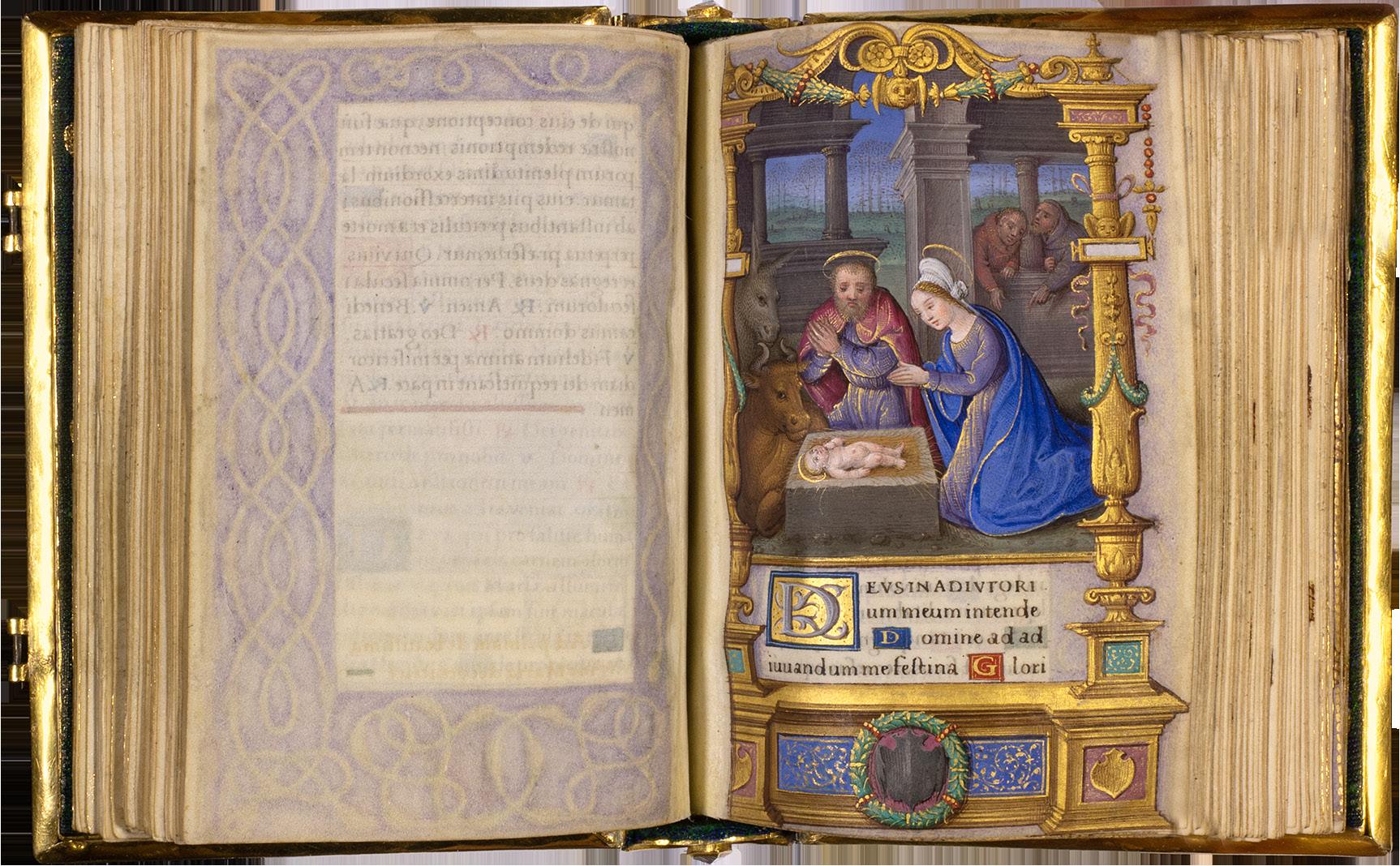

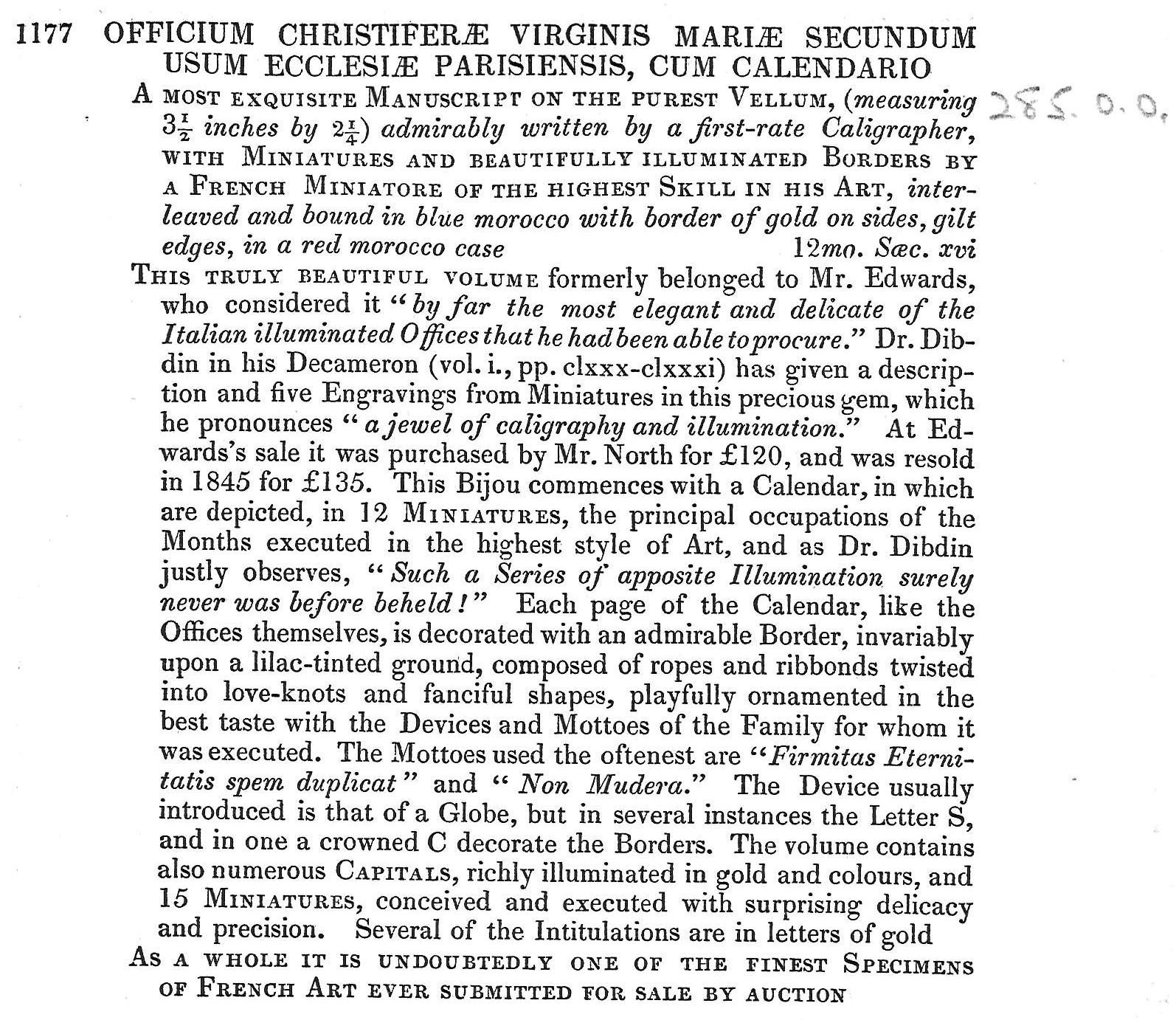

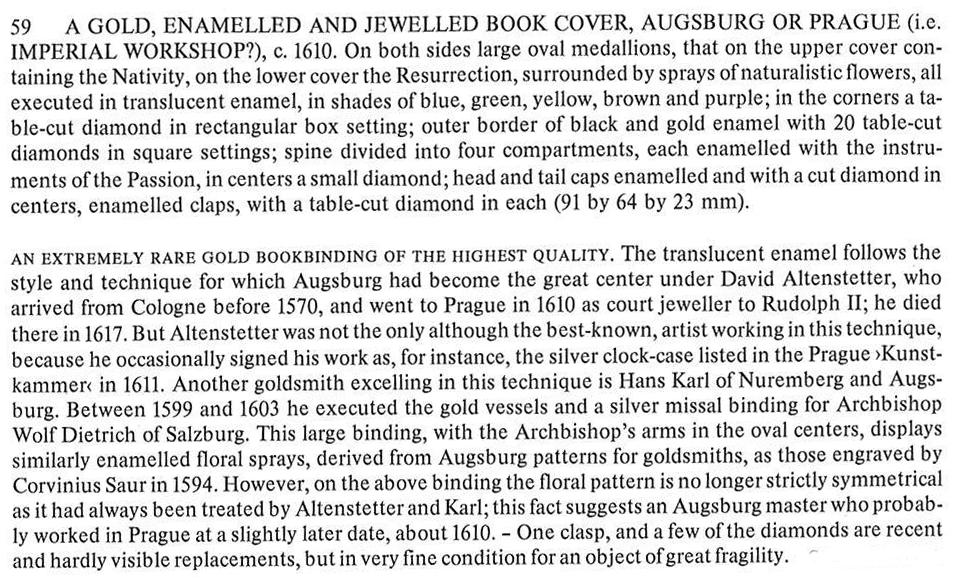

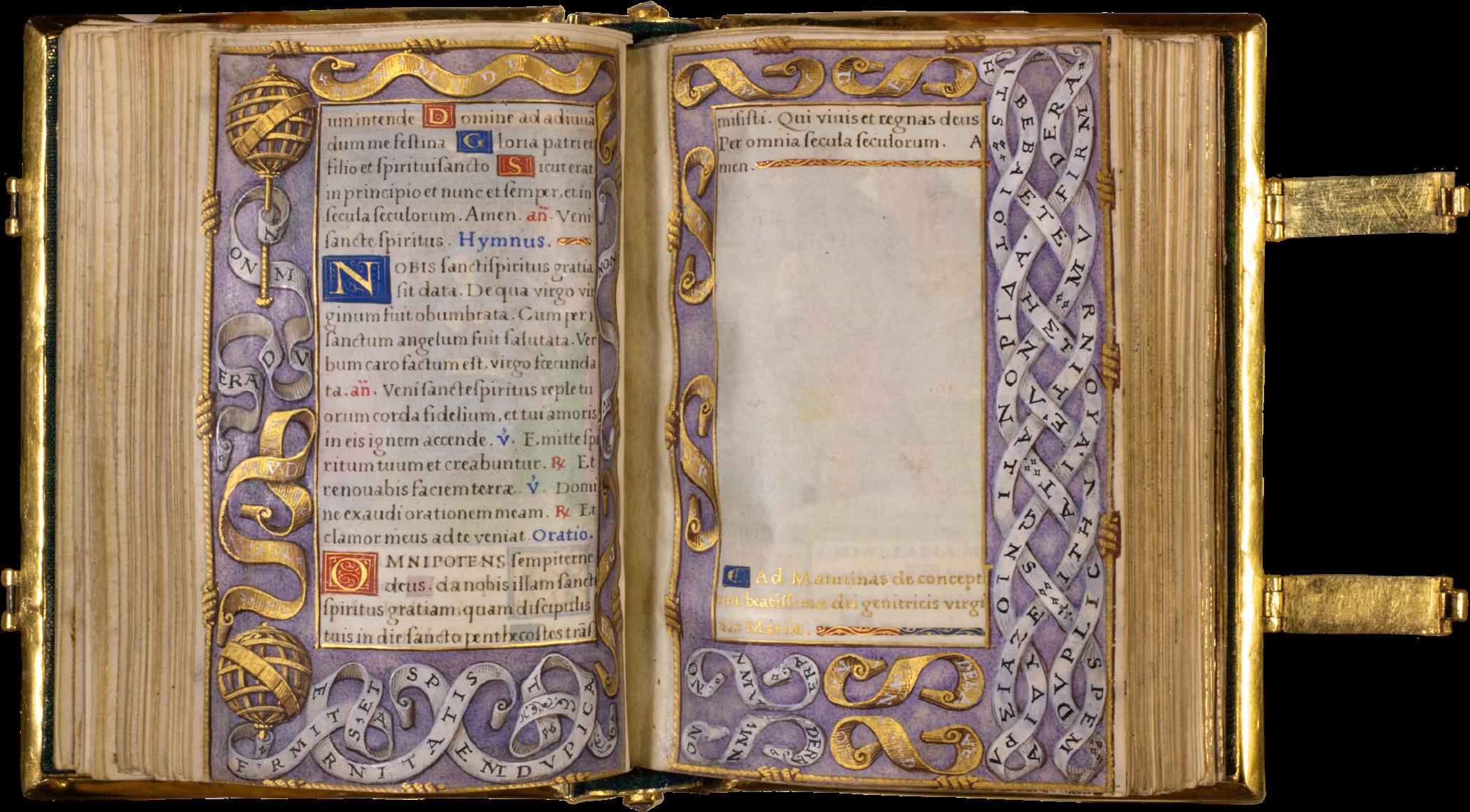

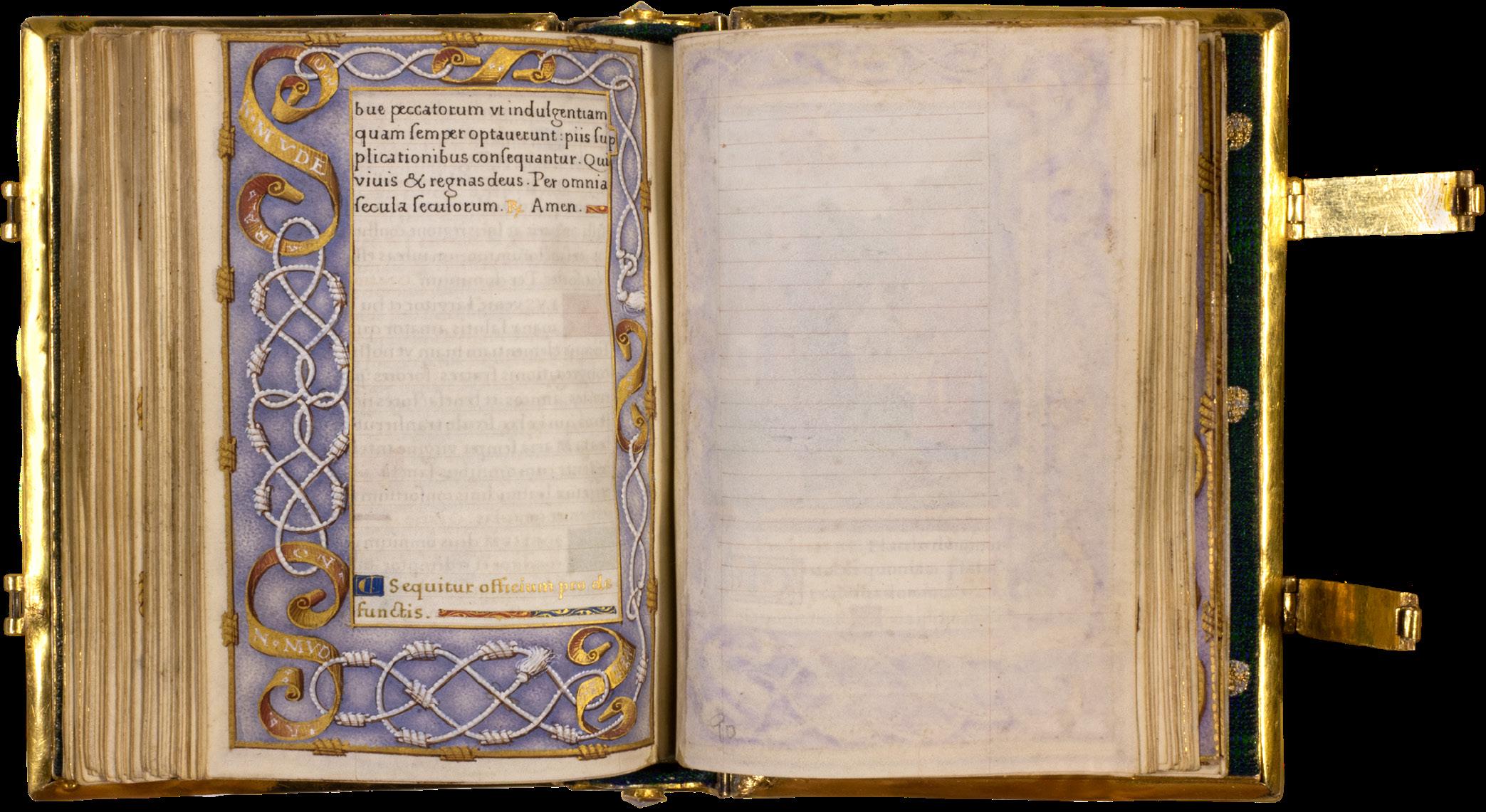

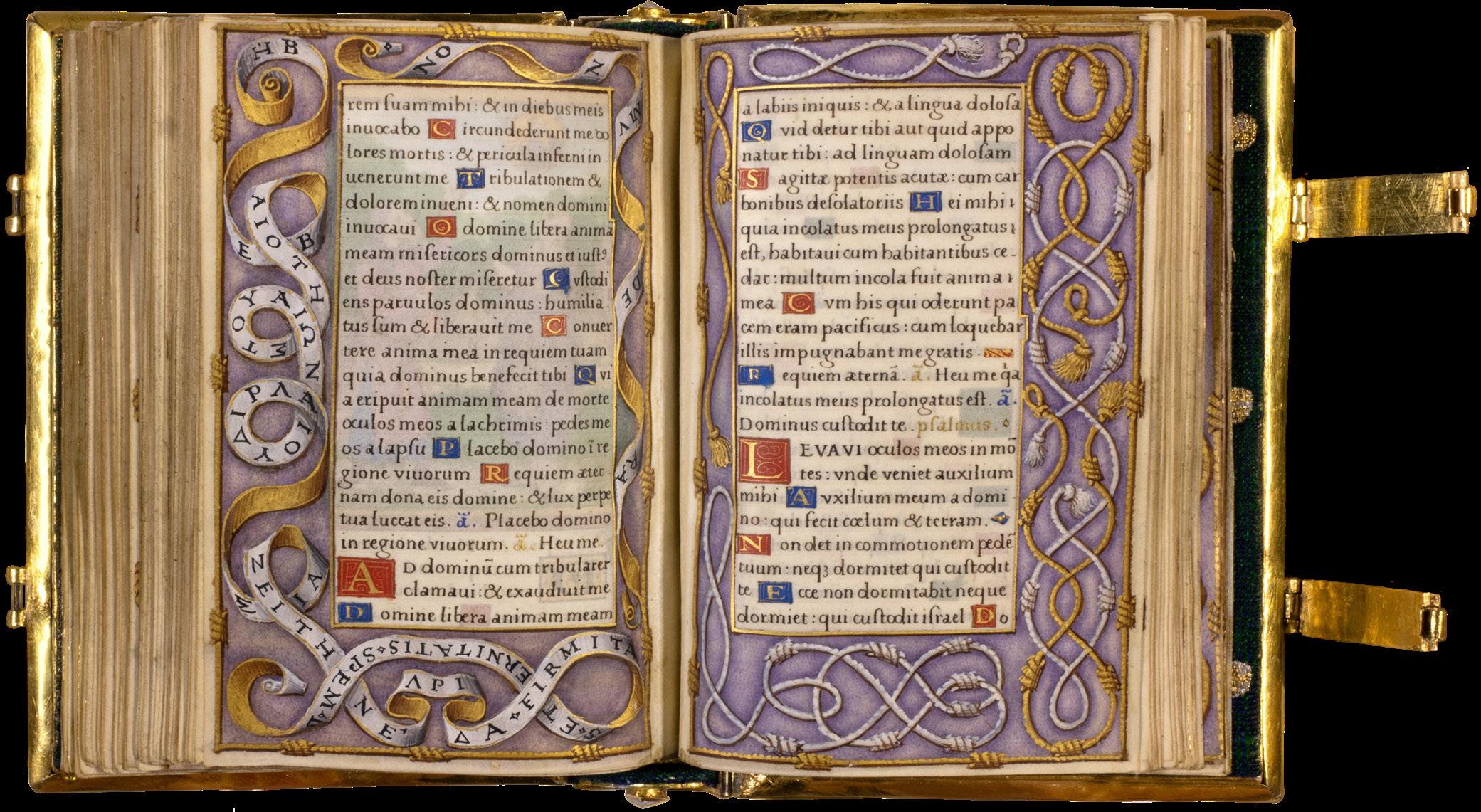

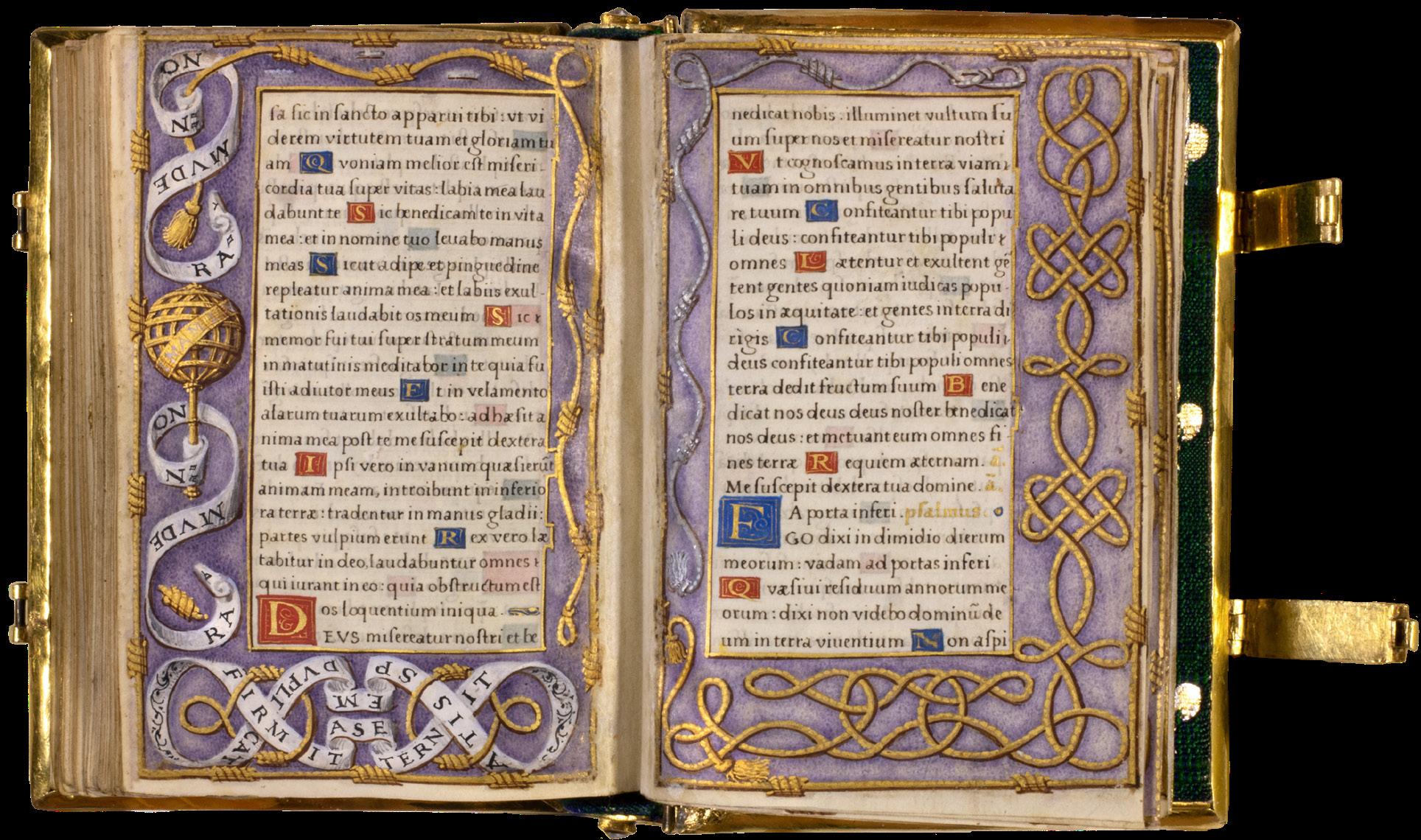

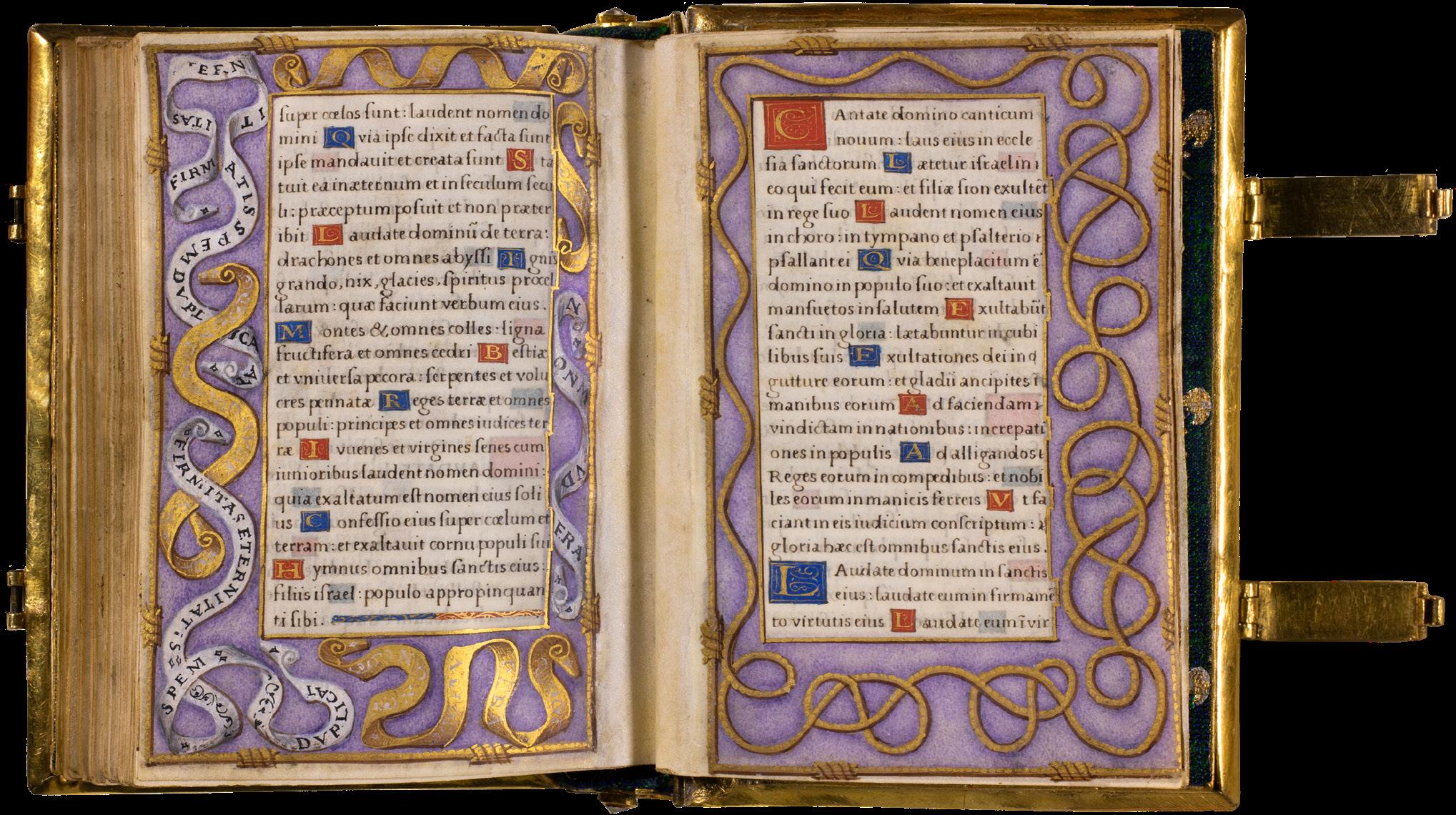

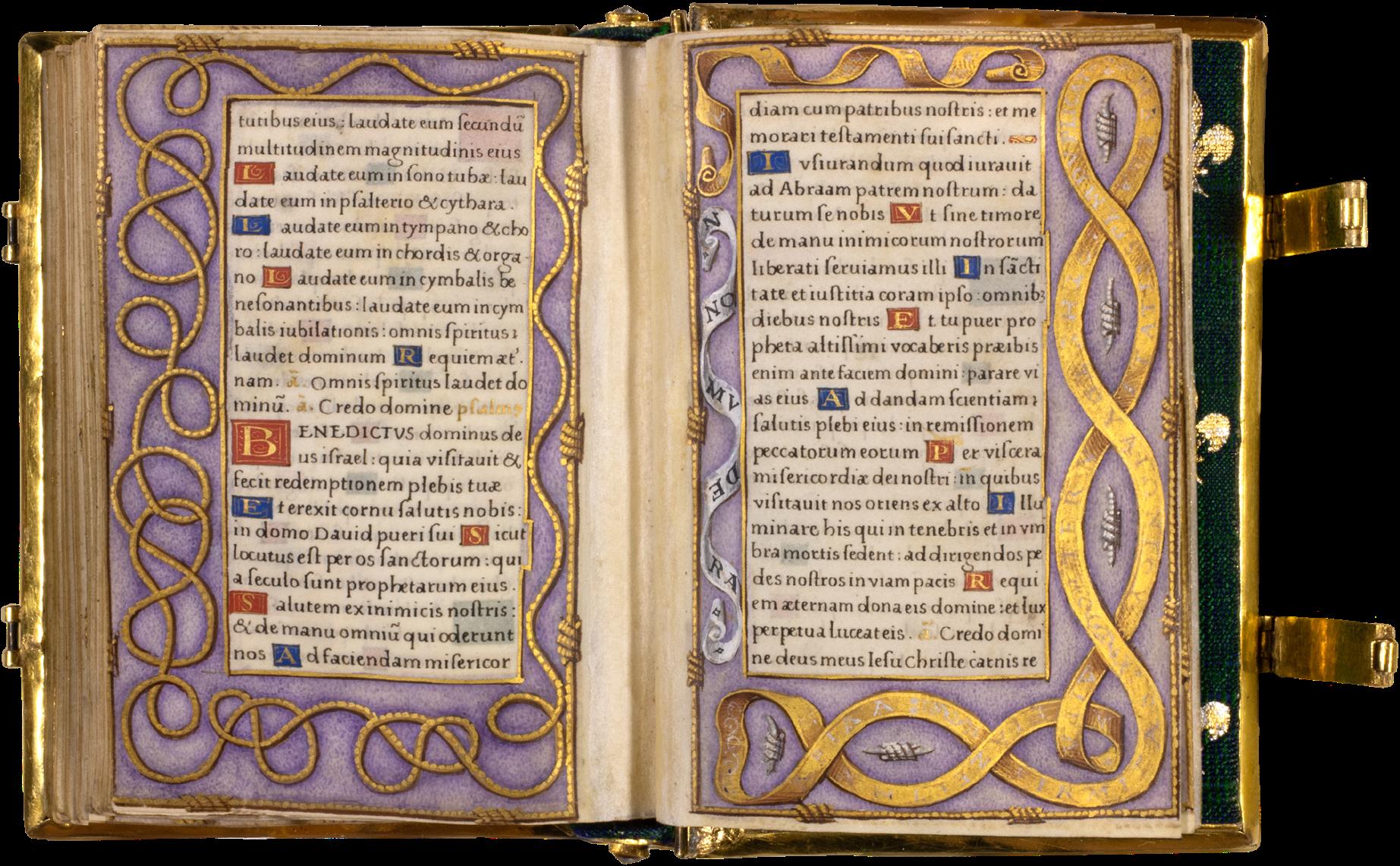

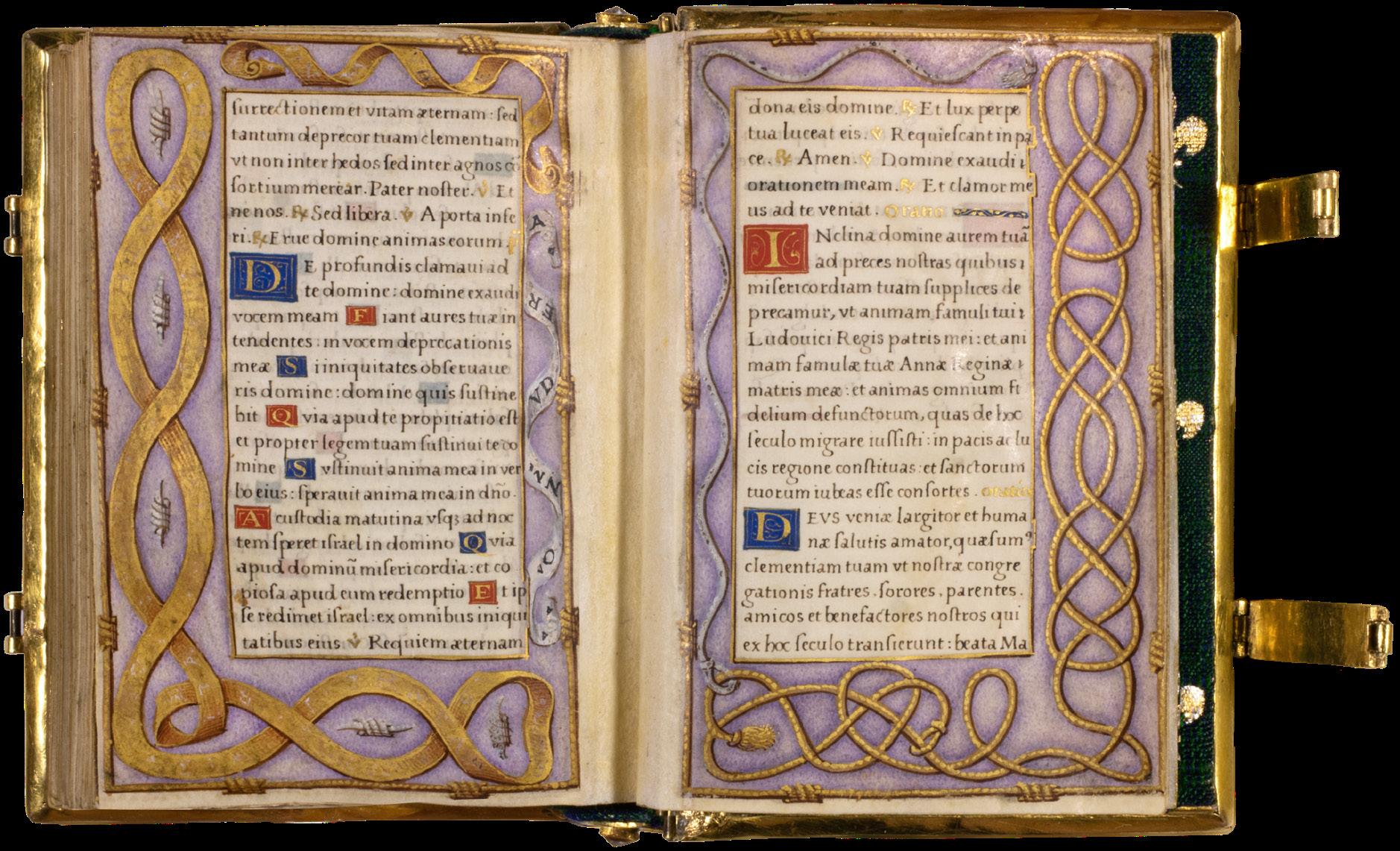

The Hours of Queen Claude of France (1499-1524), which was bound with inserted protective paper leaves in the early nineteenth century, has now been rebound in a gold enamel and jewelled book cover made in Prague under the reign of Emperor Rudolph II. Sophisticated enamel medallions commemorate Christmas Night and Easter on the upper and lower cover and the Redemption in four compartments with the Arma Christi on the spine. The binding is a rare and precious example of goldsmith’s art flourishing first in Augsburg and Munich in the last quarter of the sixteenth century and triumphant at the Imperial court of Prague. It includes exquisite deep-cut enamels, a practice first developed by David Altenstetter (1547-1617) in Augsburg, before the goldsmith started to work in Prague at the court of Rudolph II. As far as we know, Altenstetter always used a silver ground for his enamelled works, so he cannot be identified with the creator of this binding. But others, like the ingenious Hans Vermeyen of Antwerp, also worked at the court of Rudolph II. Still, the creator of this precious gem set with fifty-six diamonds ultimately has to remain anonymous, since the work is unmarked, following a common practise adopted for courtly commissions. The only work appropriate for comparison is a golden binding without images but crafted in the same technique (Leuchtendes Mittelalter VI, no. 68), which was first made for Catholic use but was reworked by the same goldsmith in a horizontal format to fit a manuscript of the Twelve Meals of Jesus, with Bible excerpts from Luther’s translation. This modification was thus supposedly undertaken in Prague during the reign of the Winter King, Frederick of the Palatinate, in 1619/20; on the other hand, the binding, which now adorns the Hours of Claude of France, was surely made in the time of Rudolph II.

4

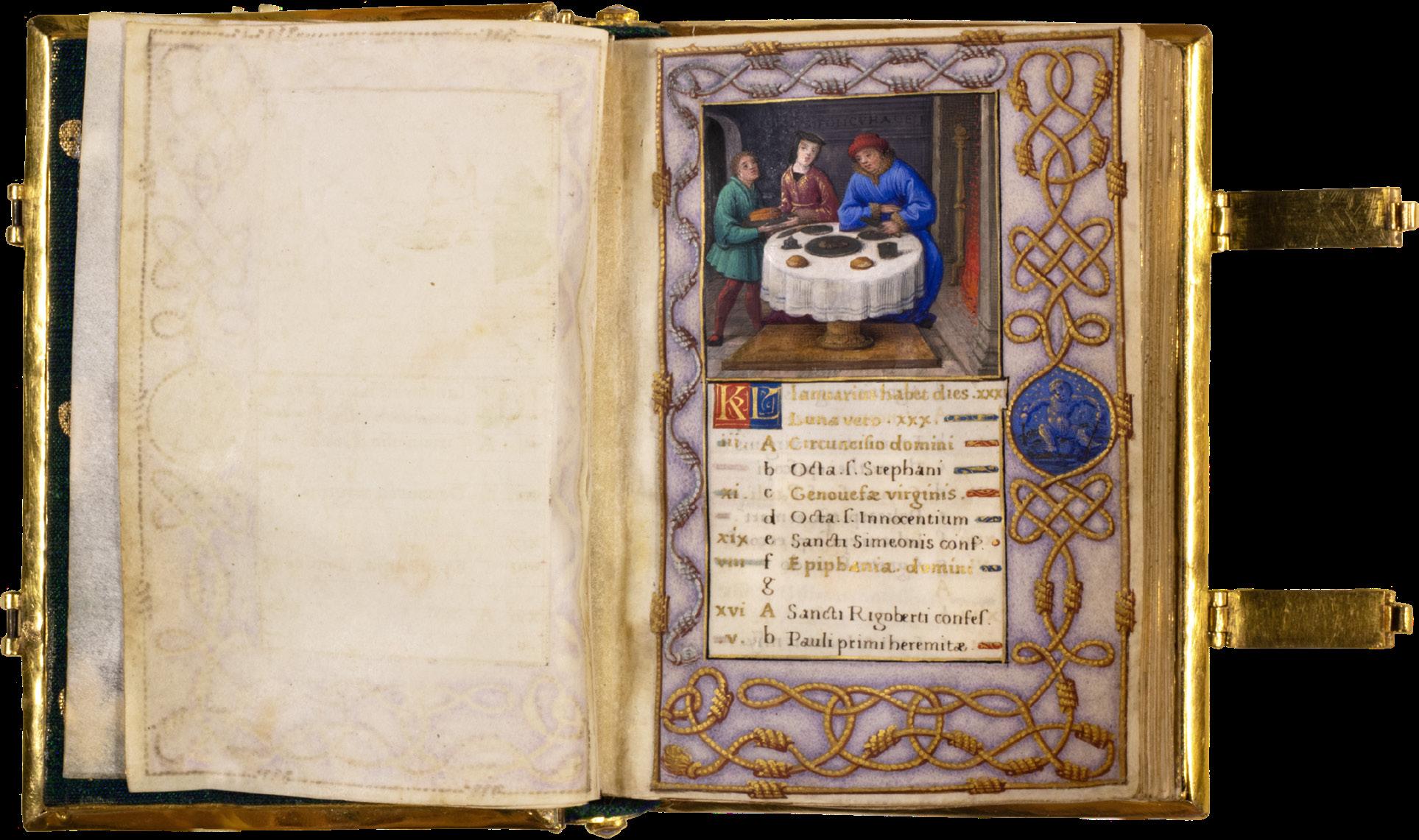

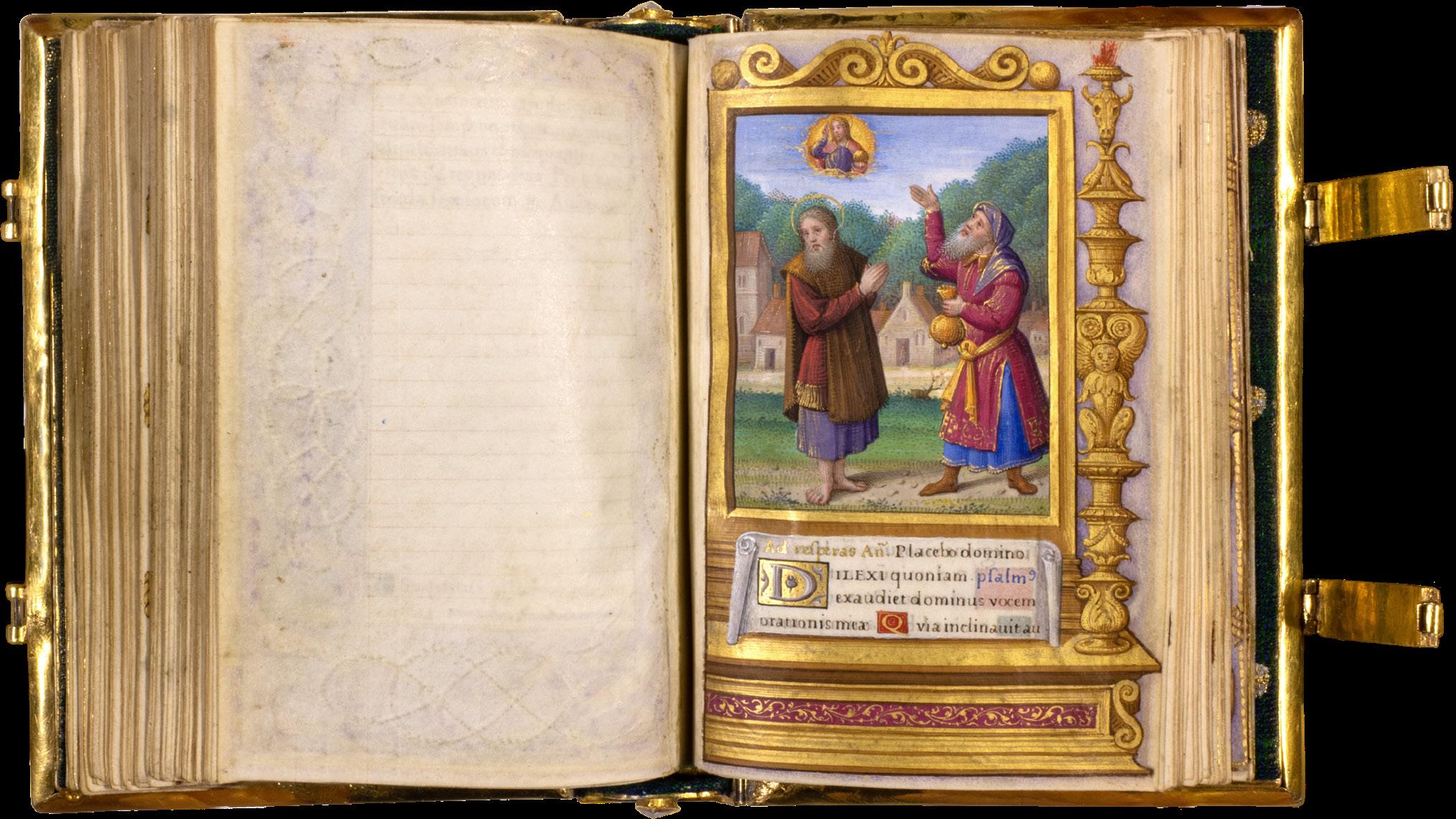

Measuring 84 by 55 millimetres, this personal Book of Hours of Queen Claude is one of those extremely miniaturised Books of Hours that had been favoured at the French court since the time of Charles VIII (died in 1498) and particularly during the time of Anne of Brittany. A prayer, which is repeated three times, intercedes for the souls of Claude’s parents, Queen Anne of Brittany (died in 1514) and King Louis XII (died in 1515). Only Queen Claude of France could have been the original owner of the manuscript, since the initial C, topped with a crown, appears on a leaf that originally showed a coat of arms with the fleur-de-lis (fol. 17/17v) that was erased by later owners.

9

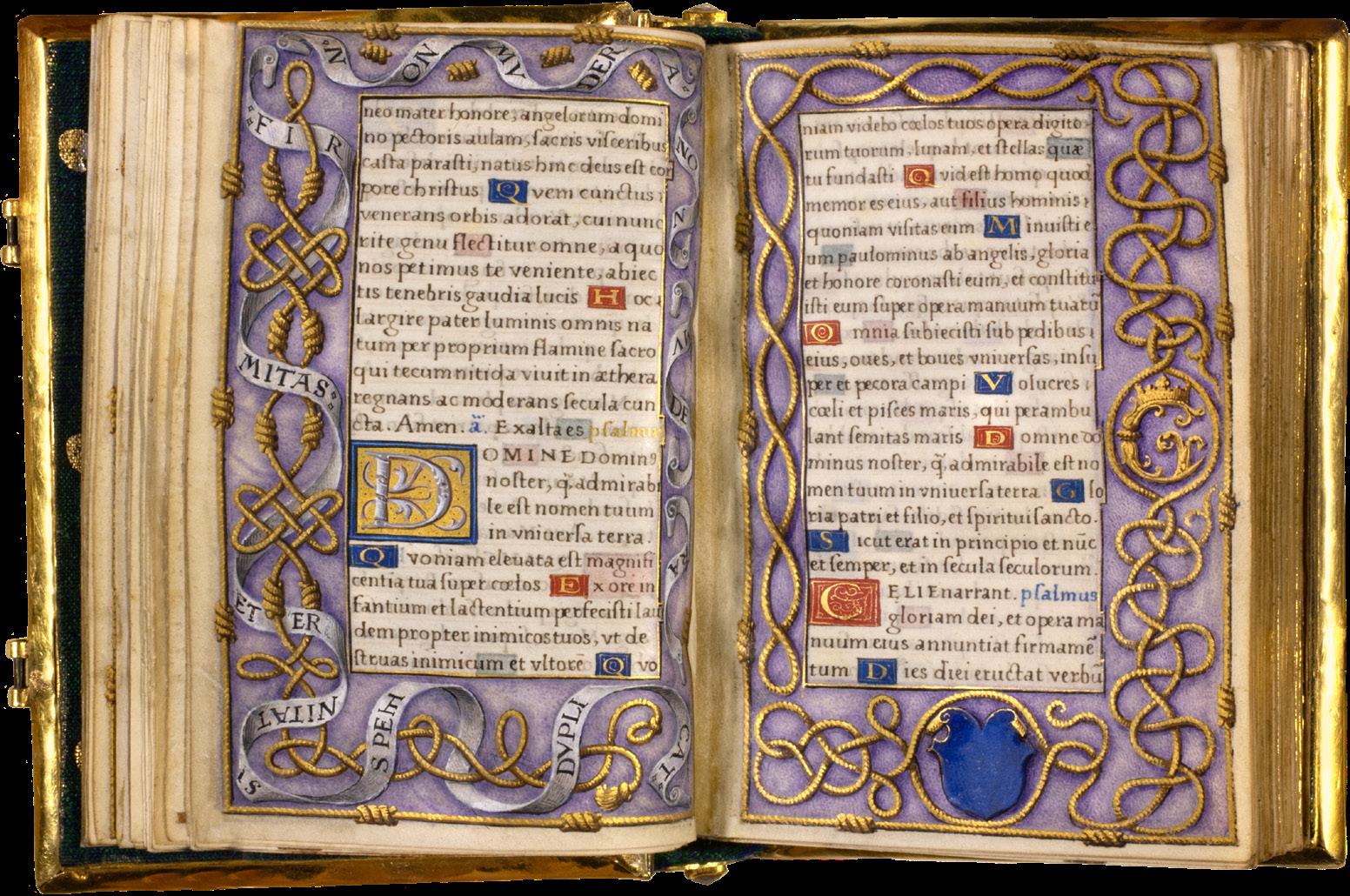

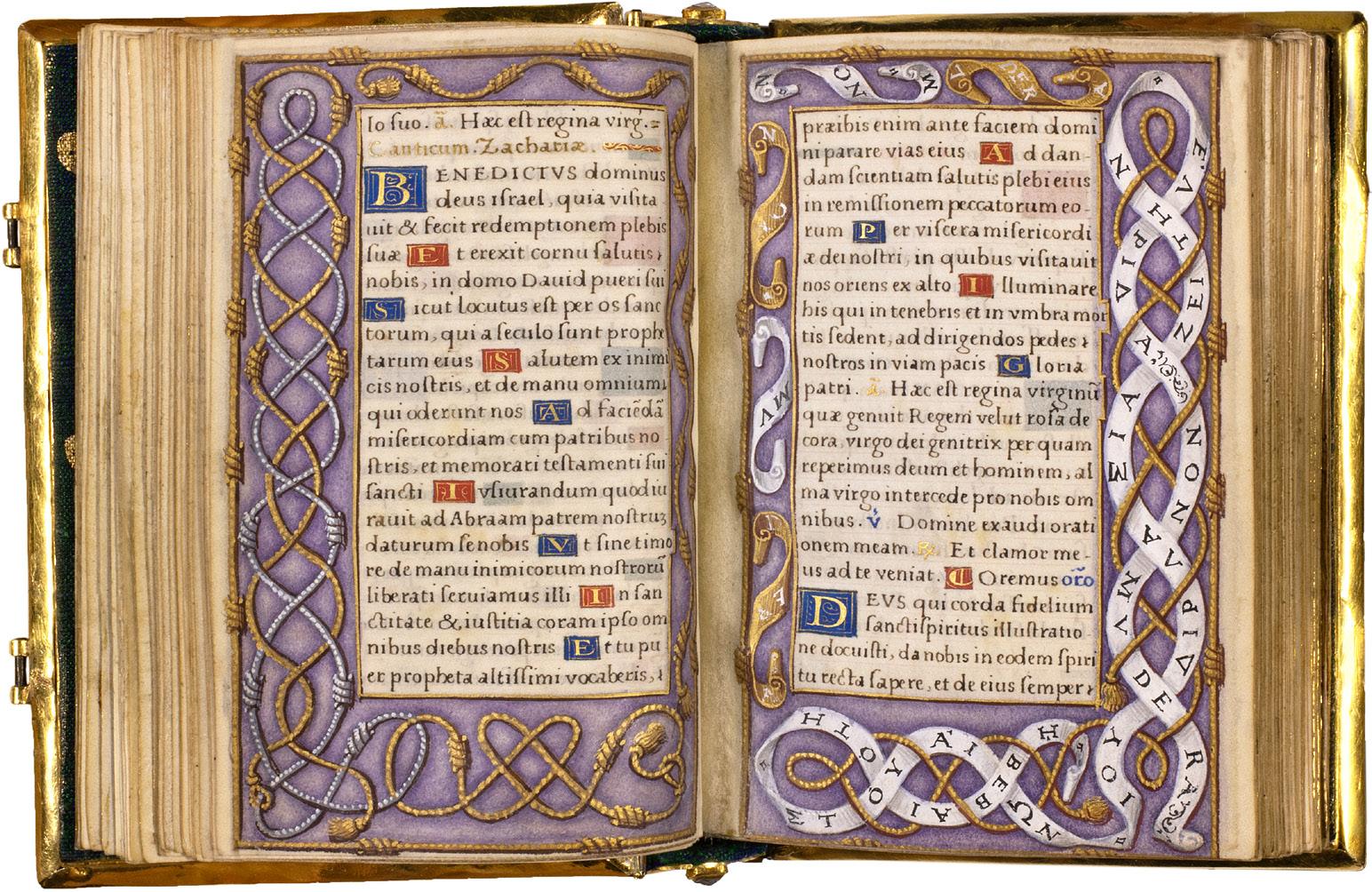

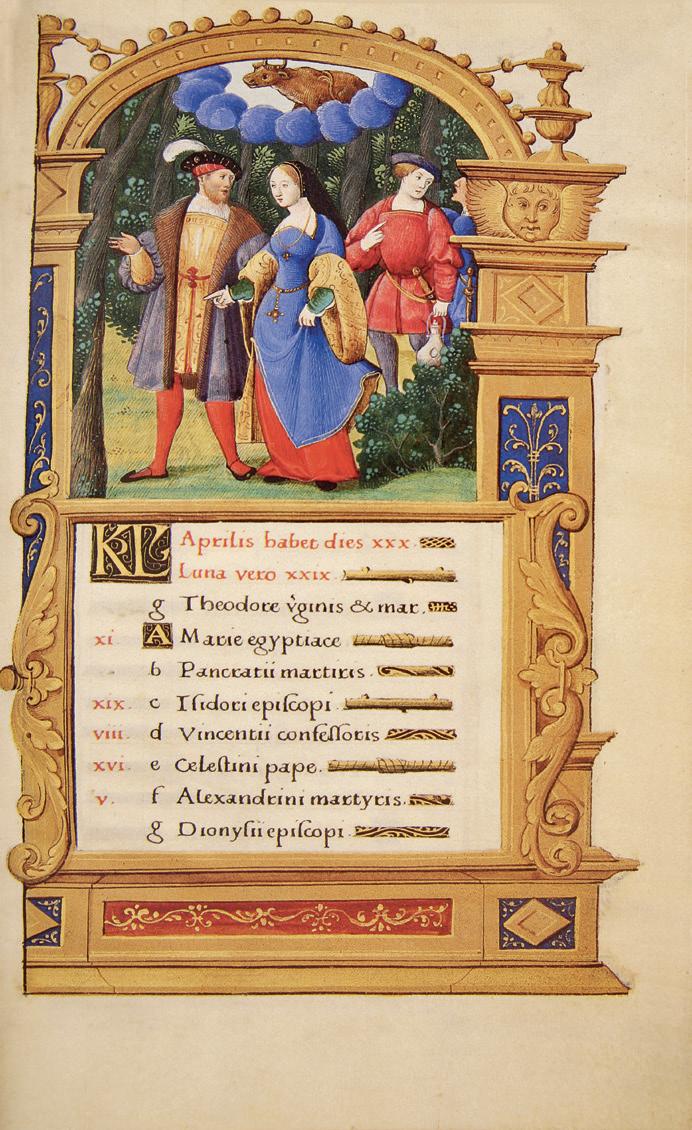

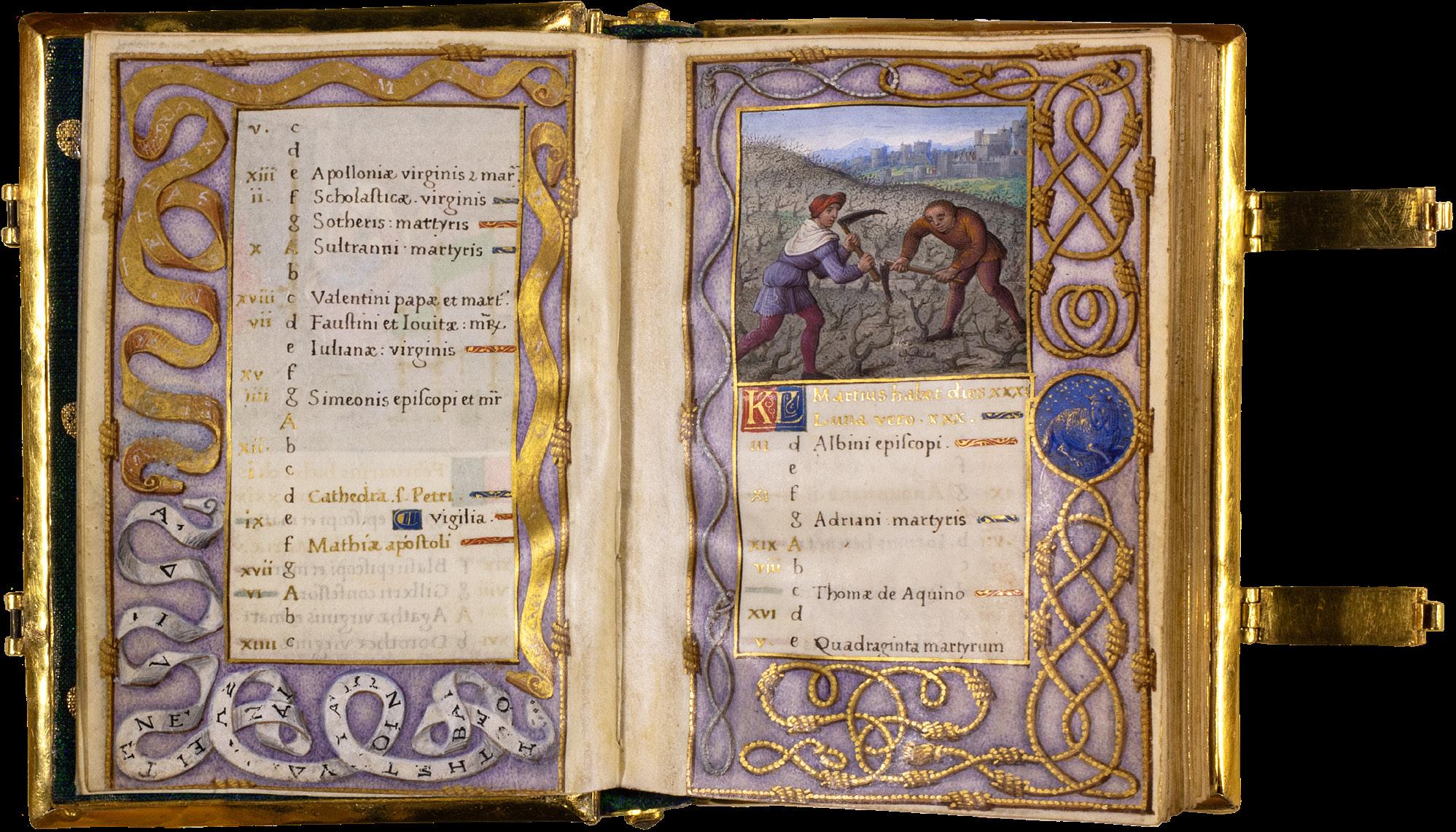

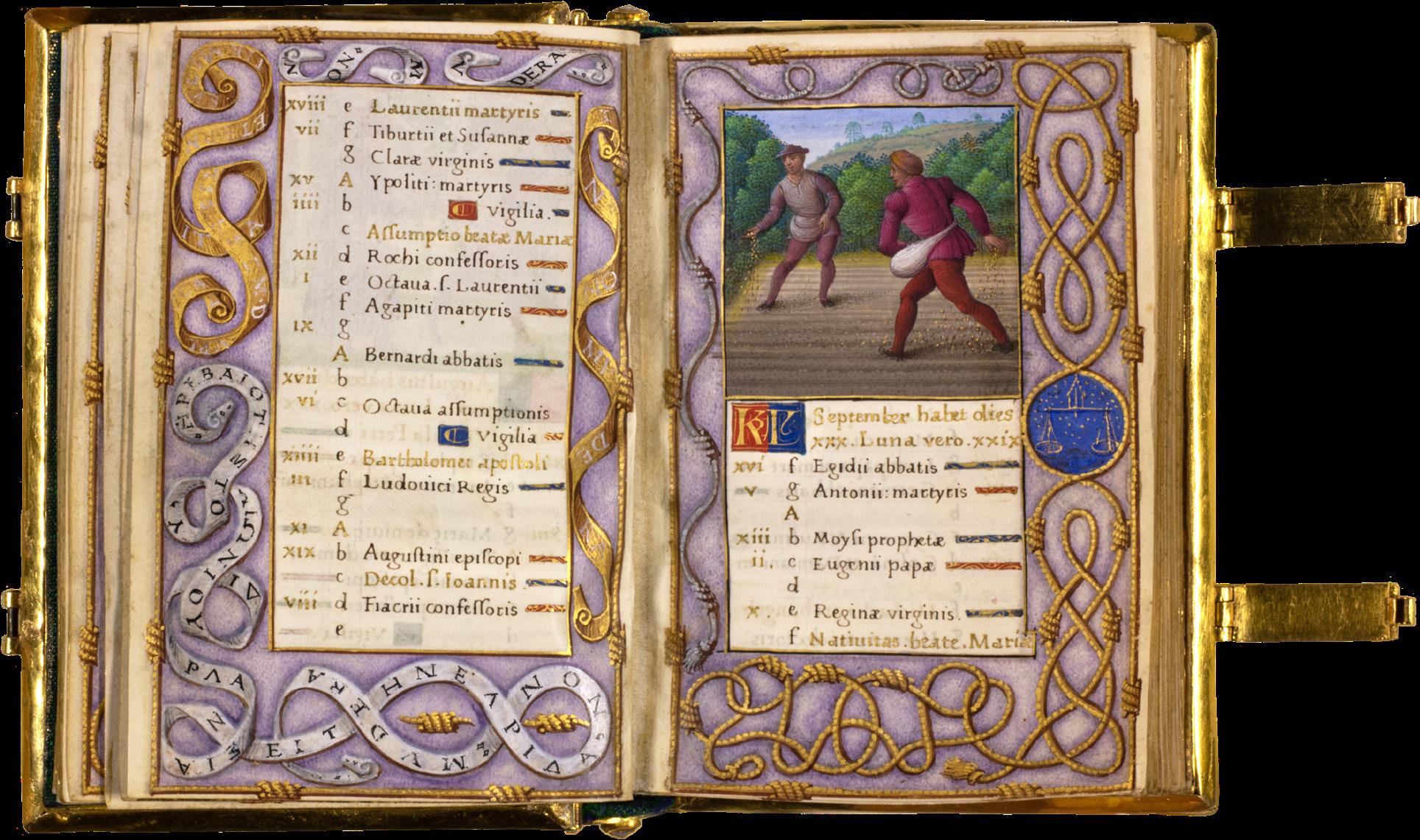

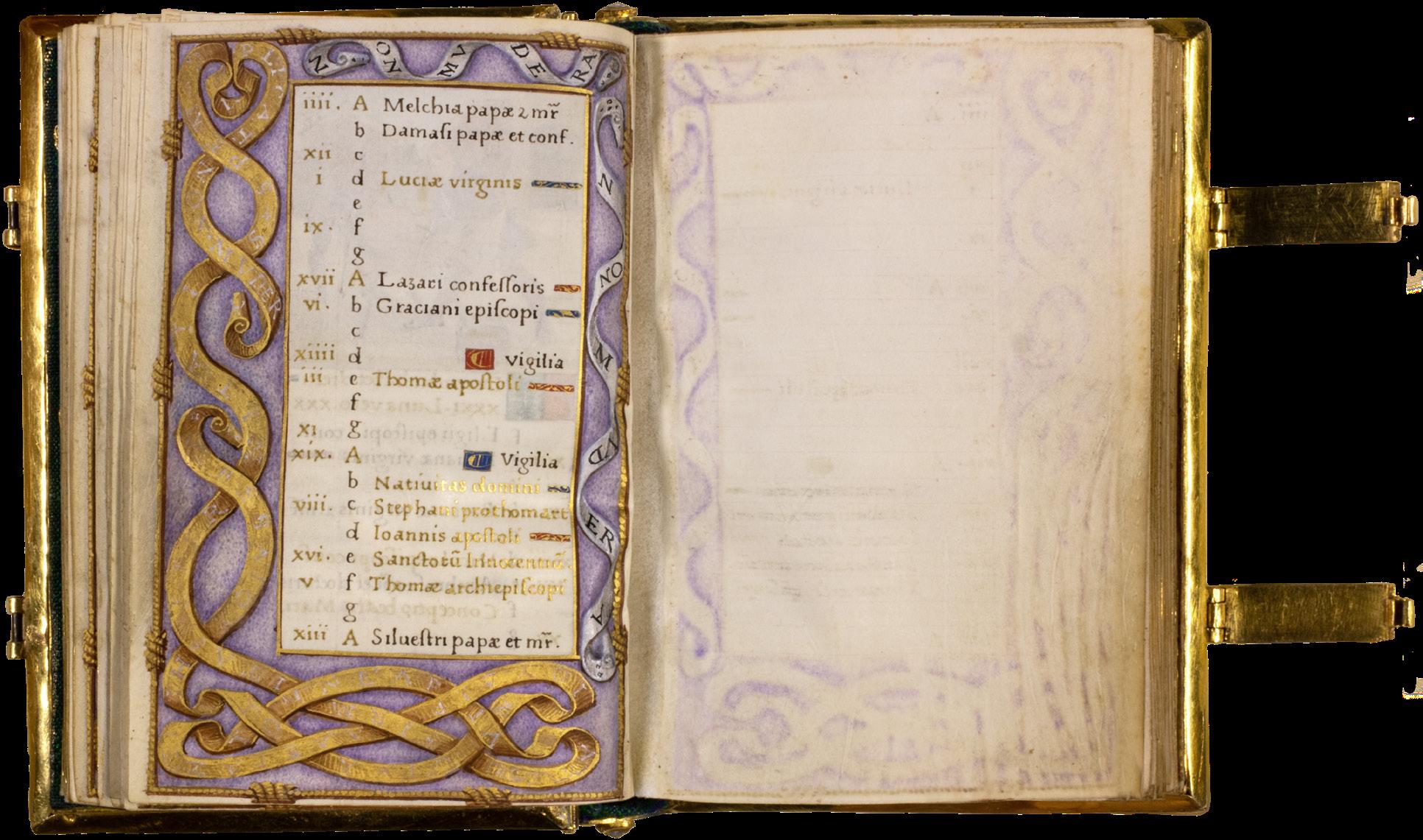

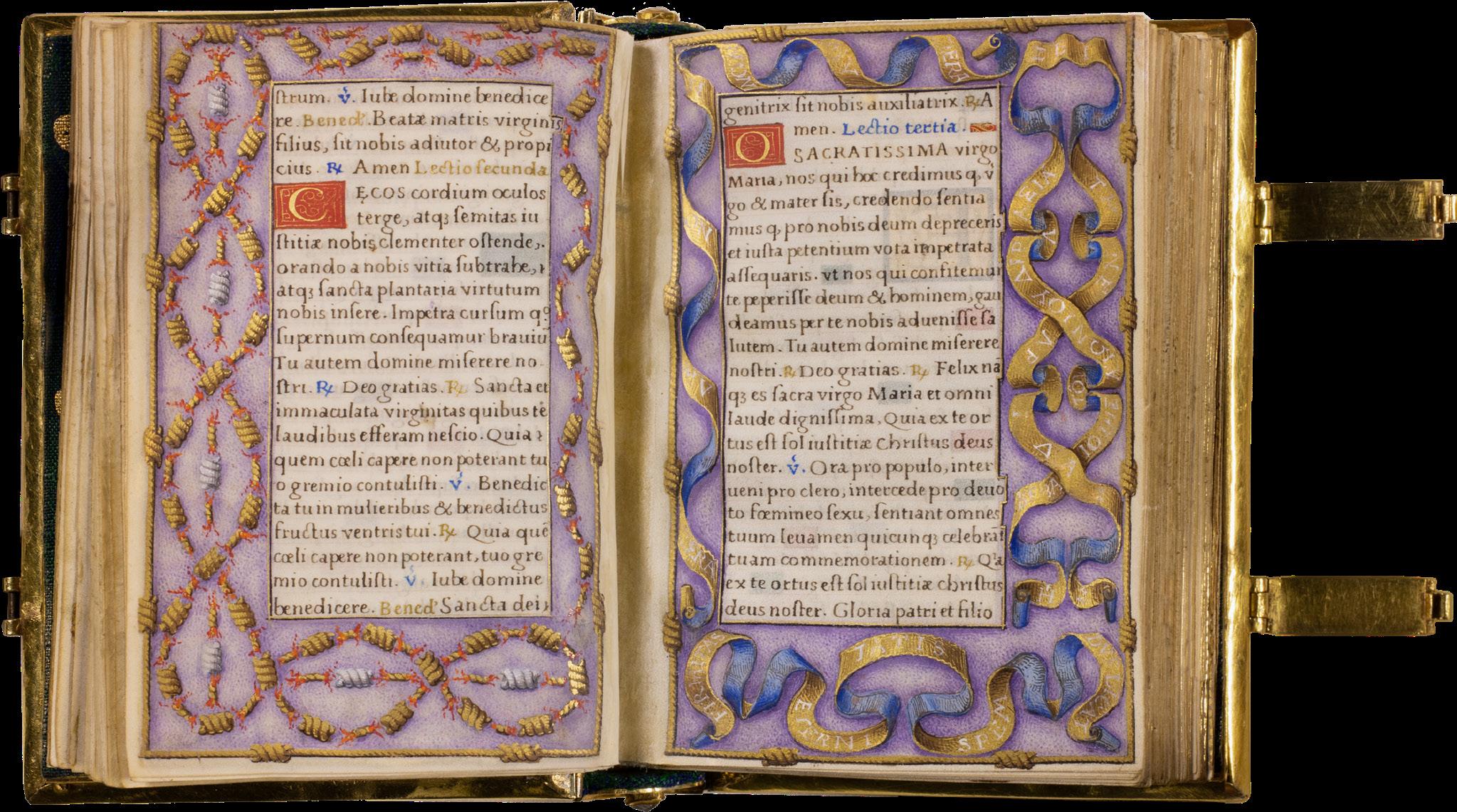

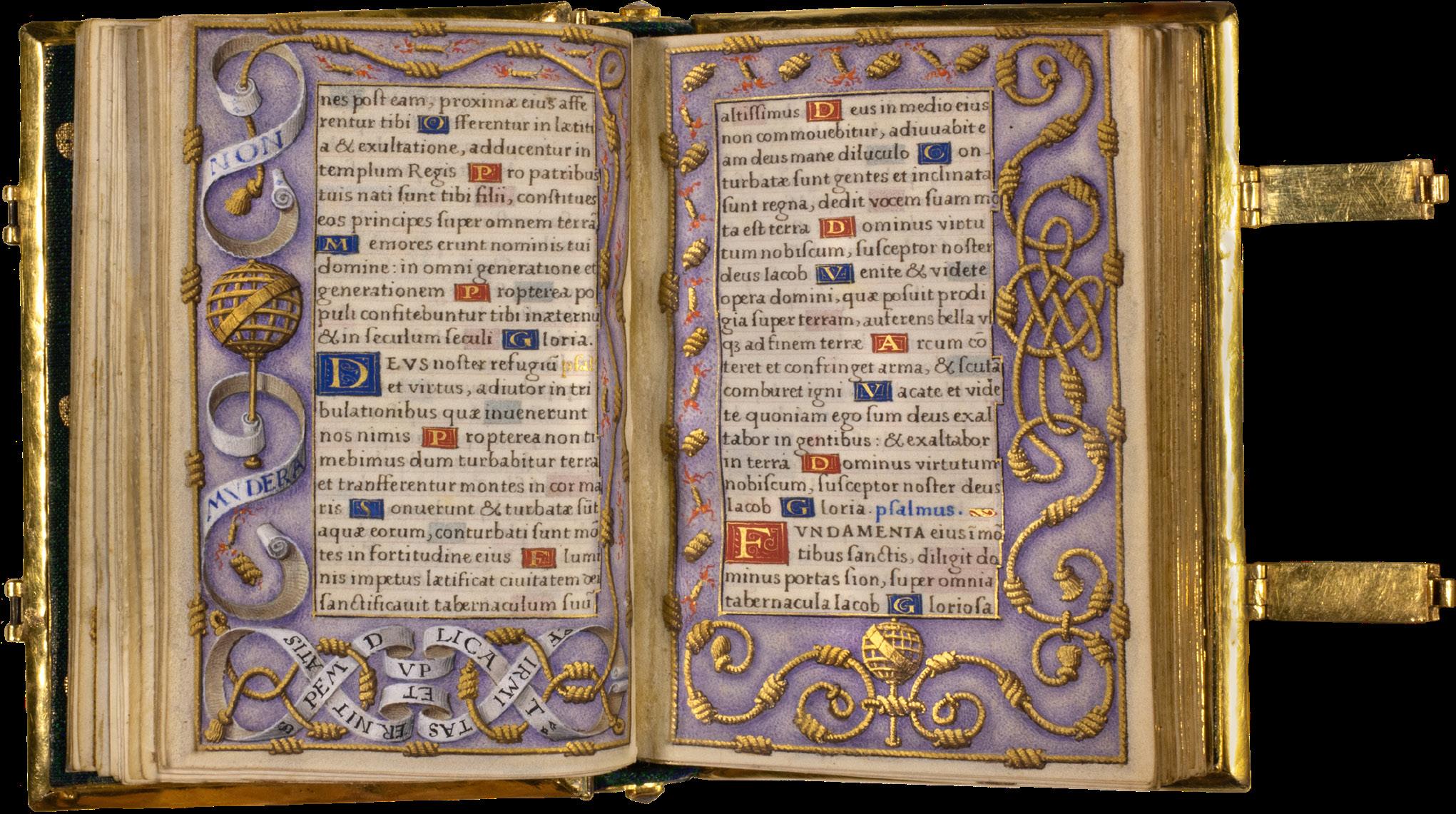

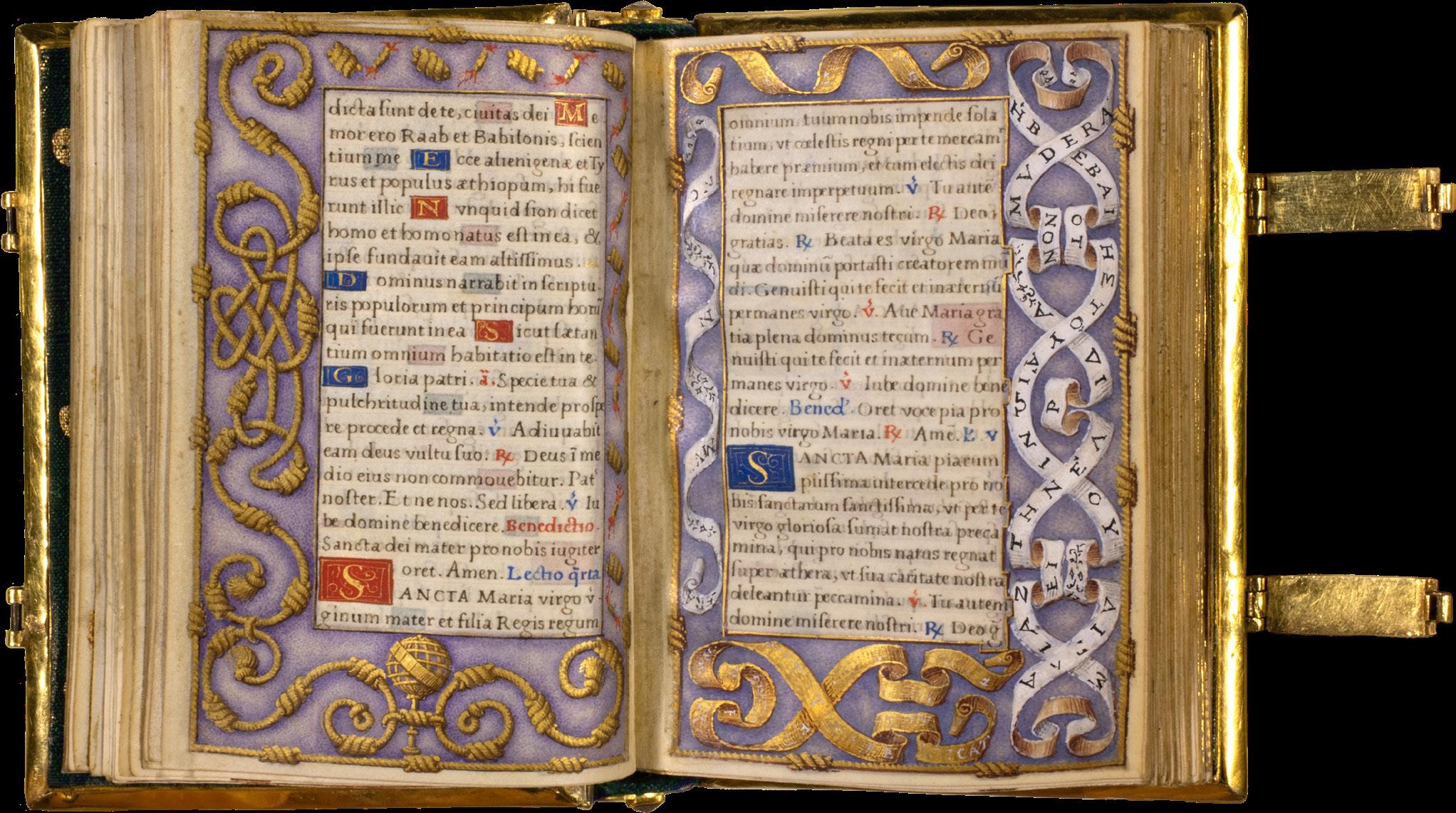

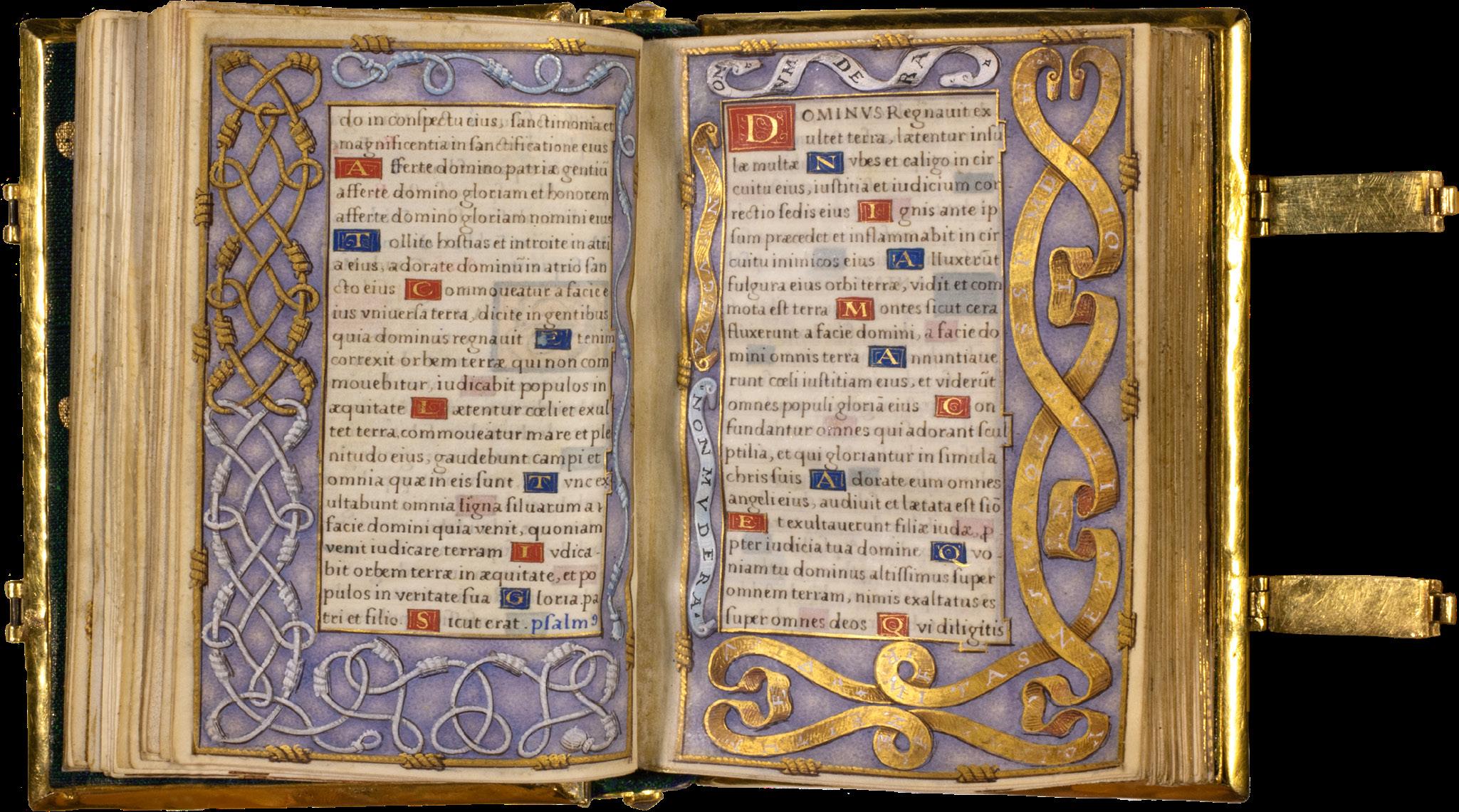

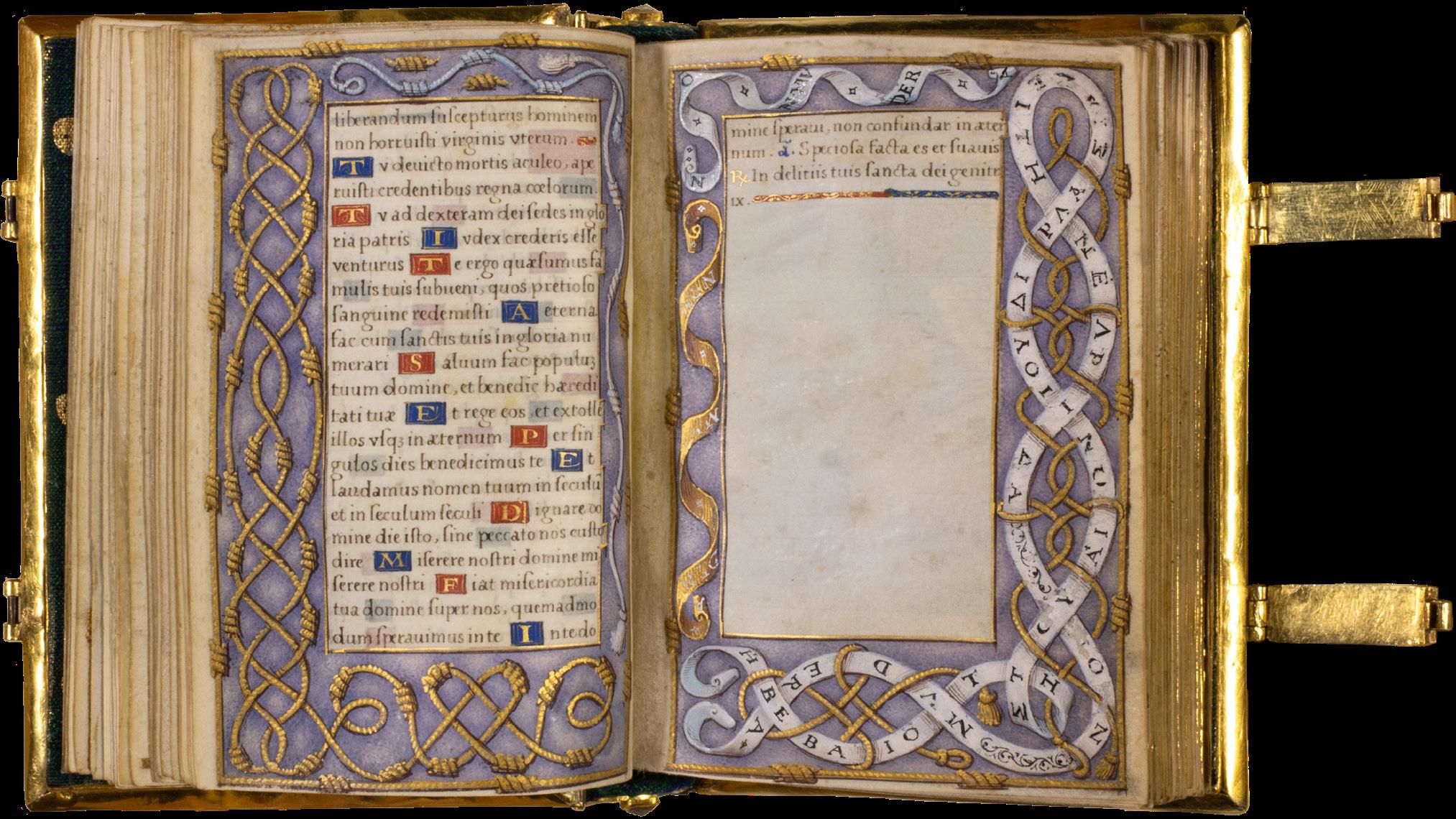

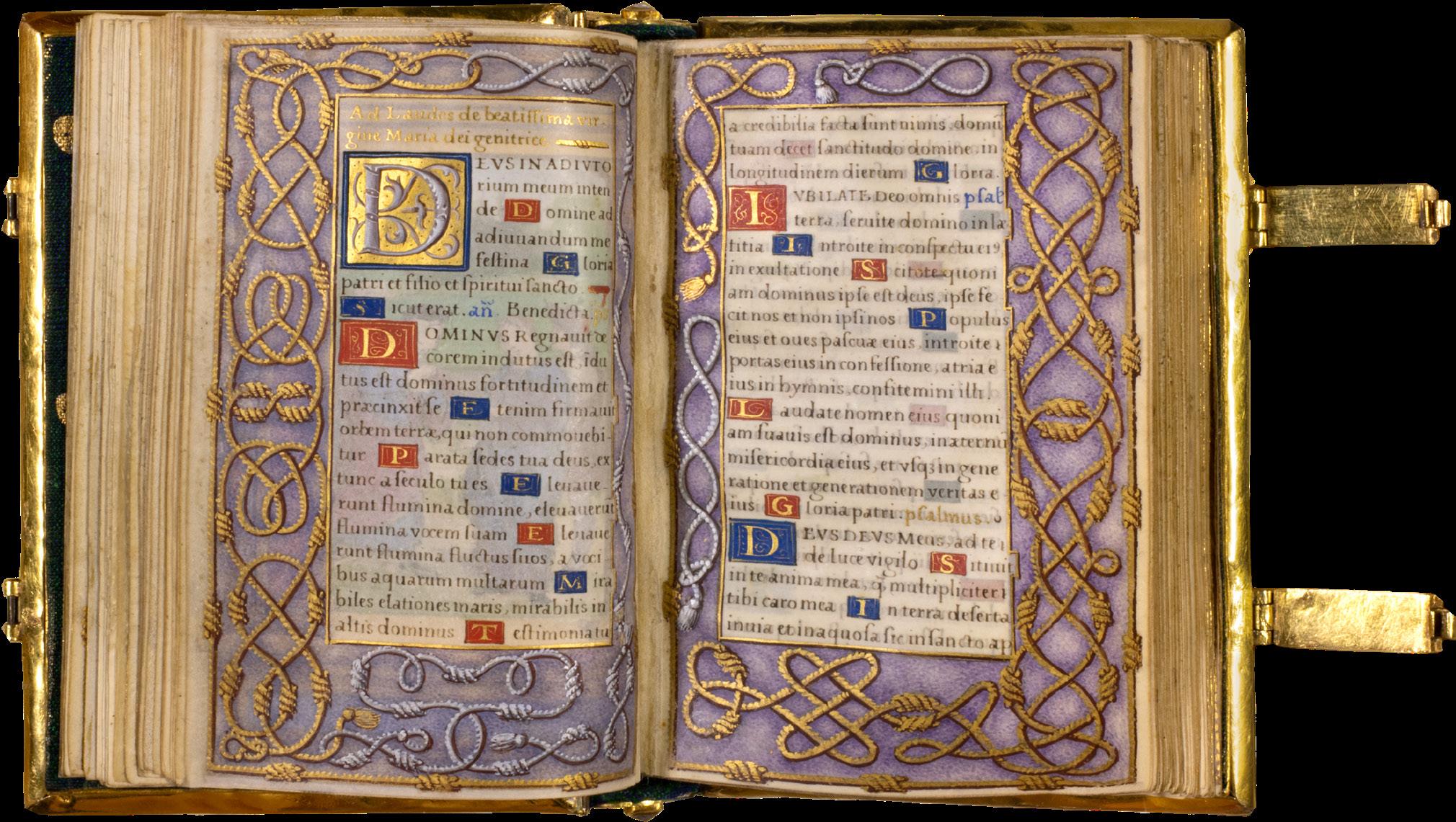

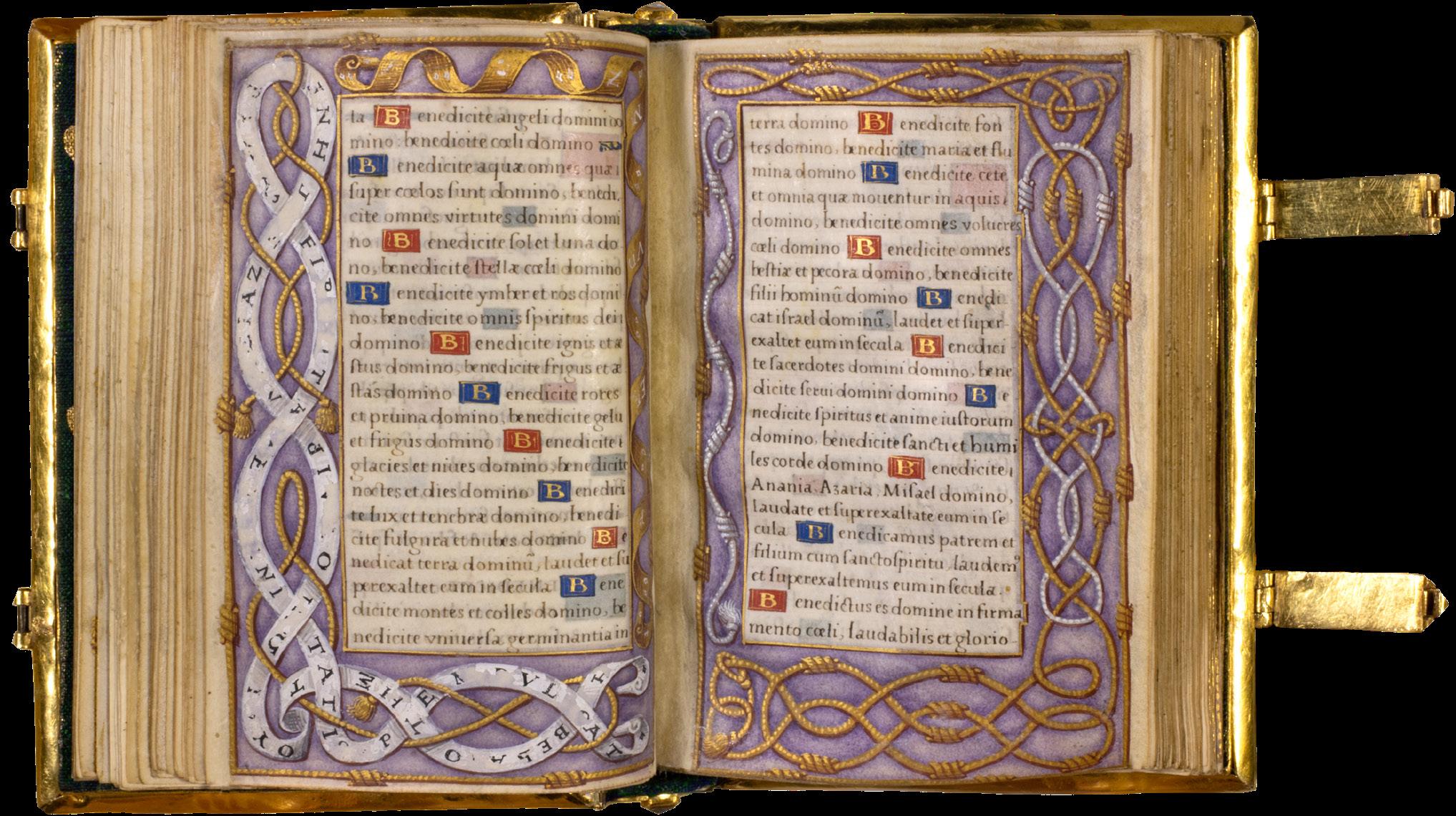

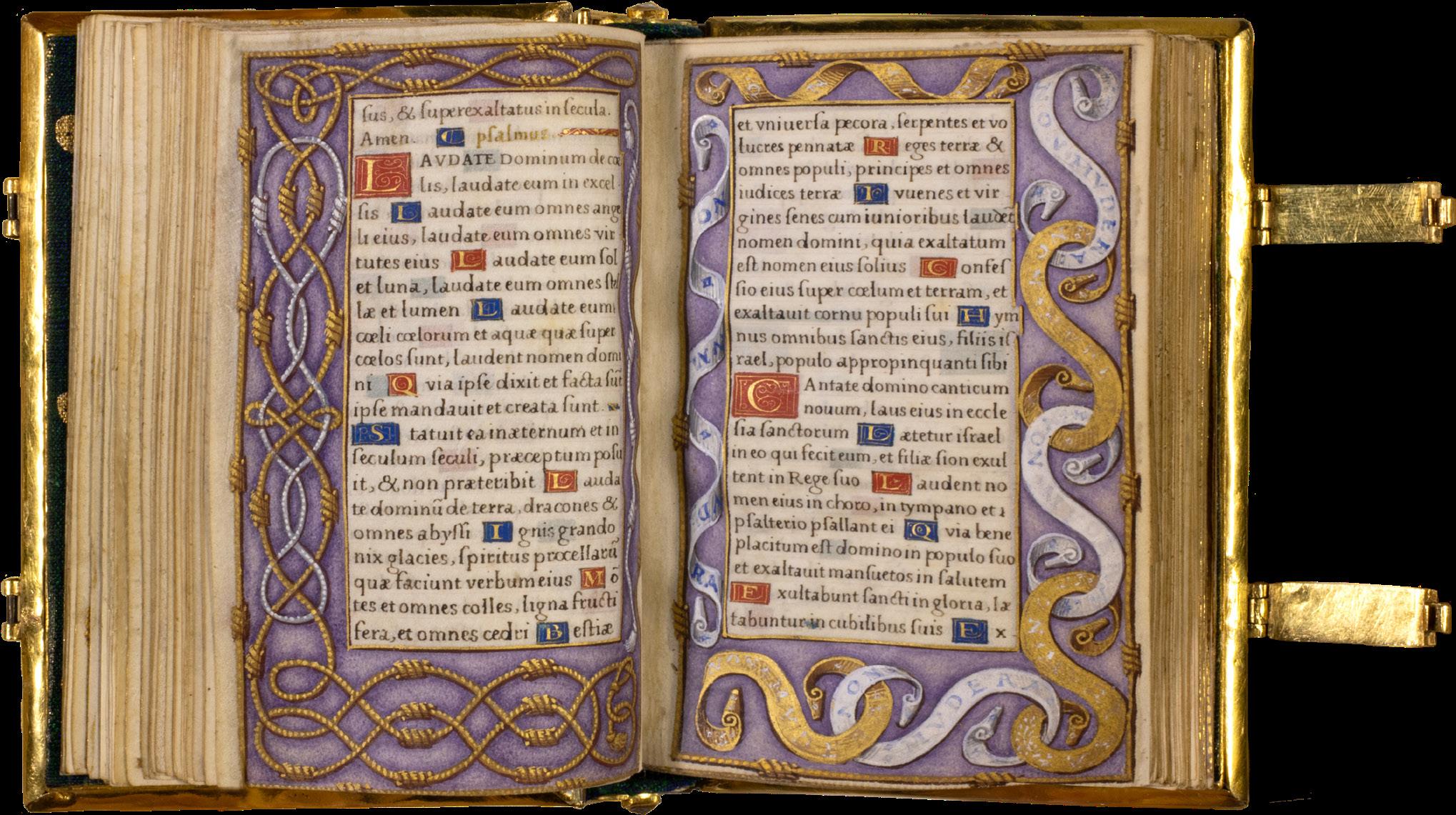

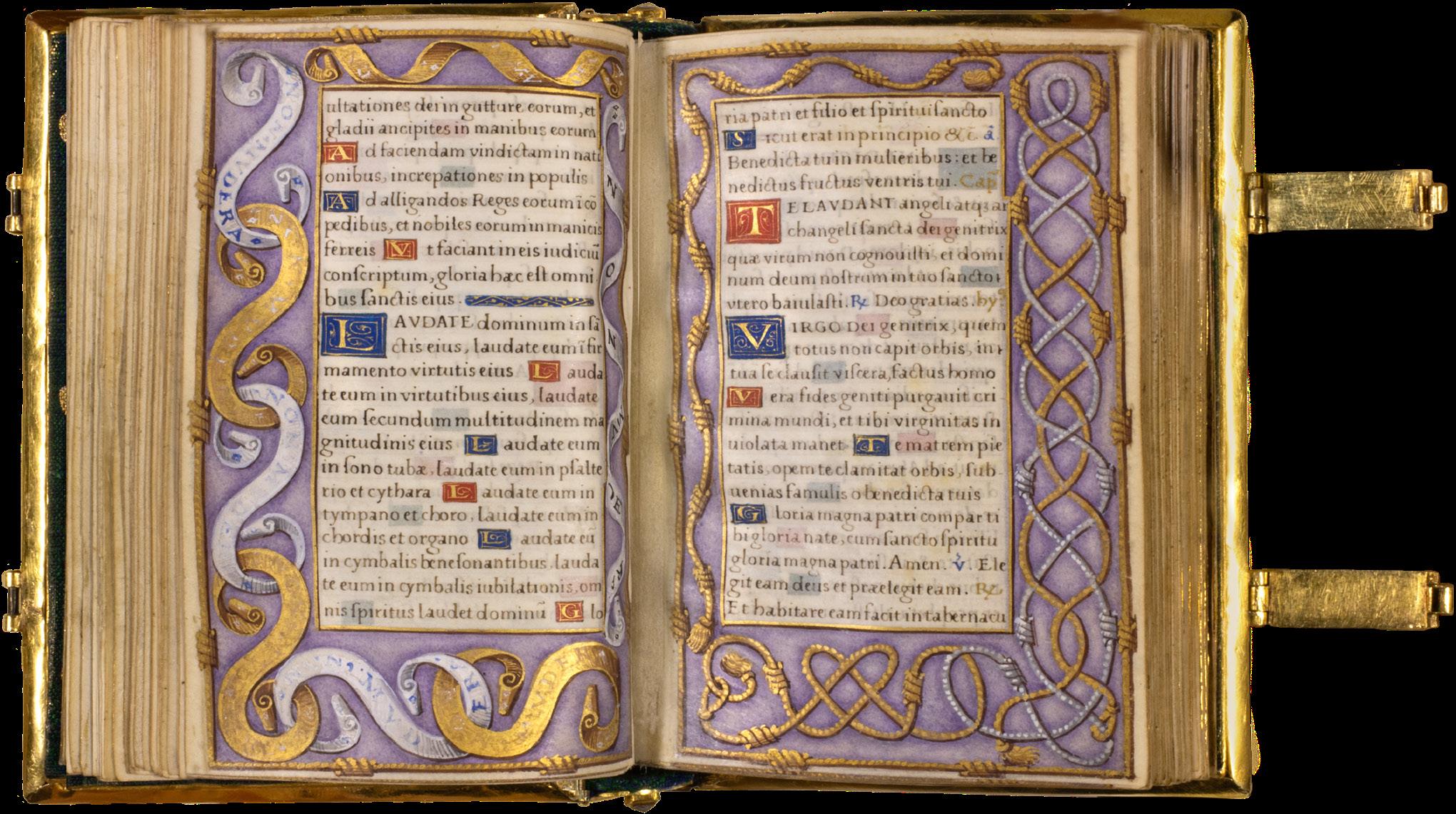

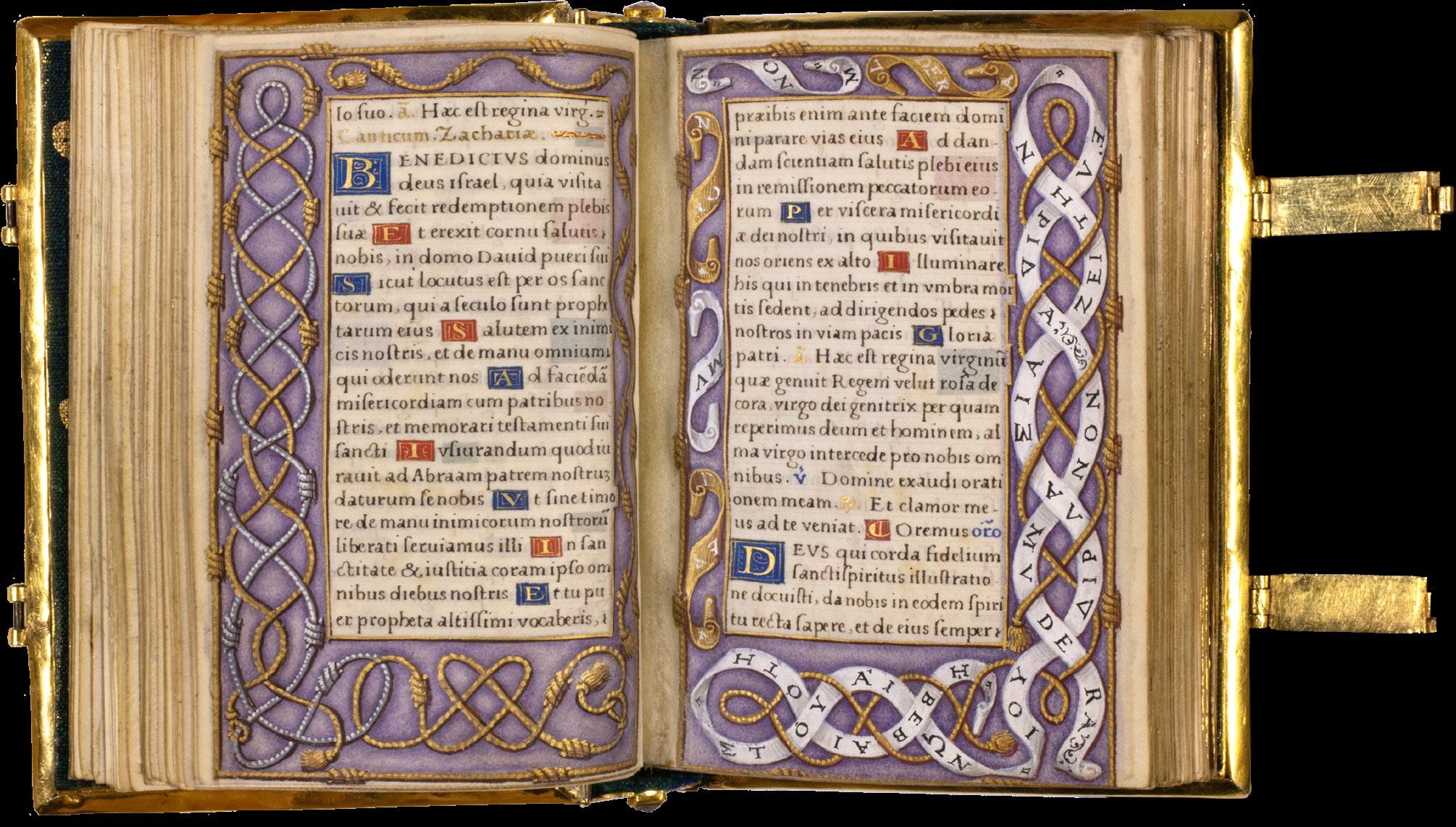

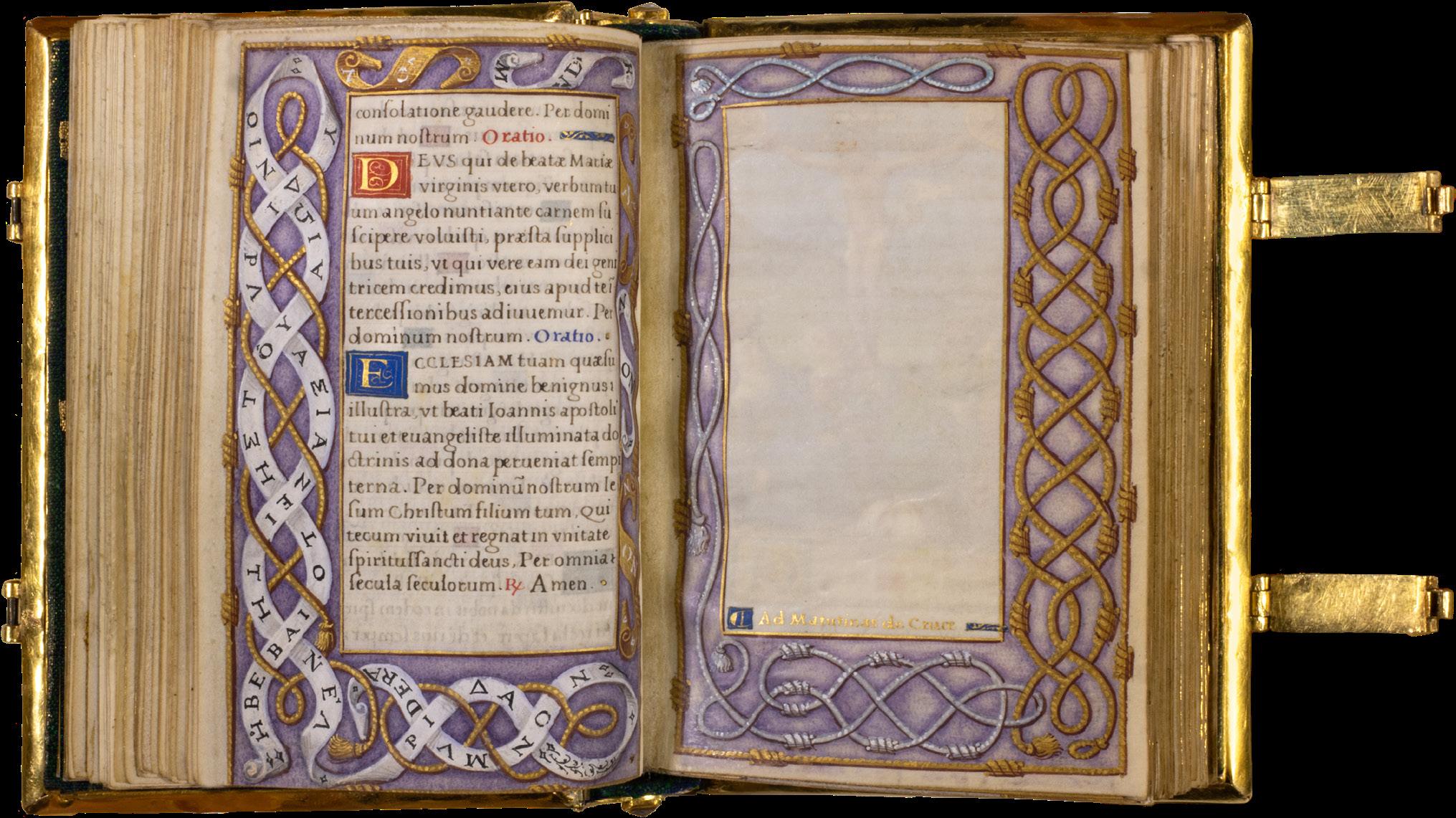

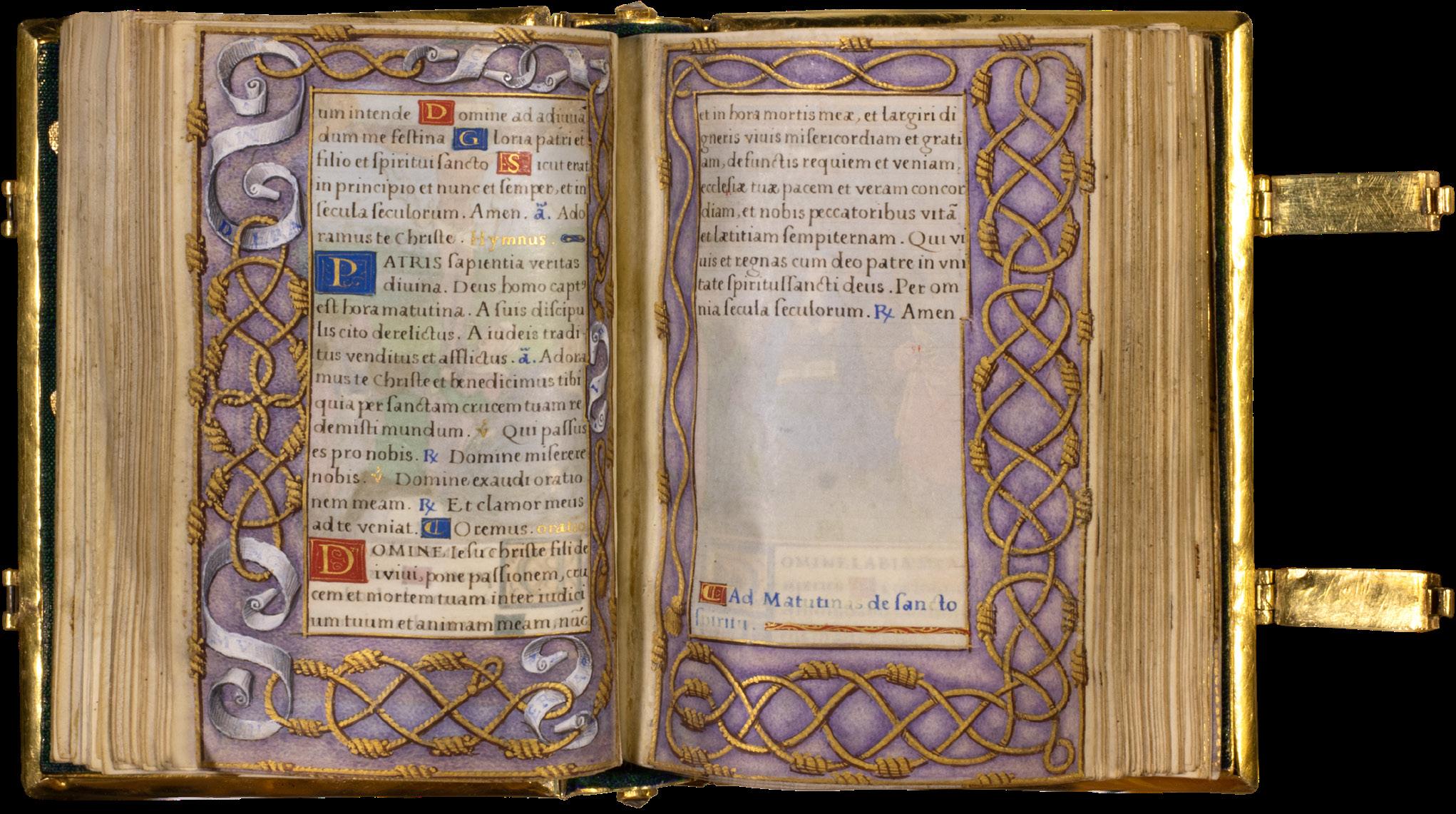

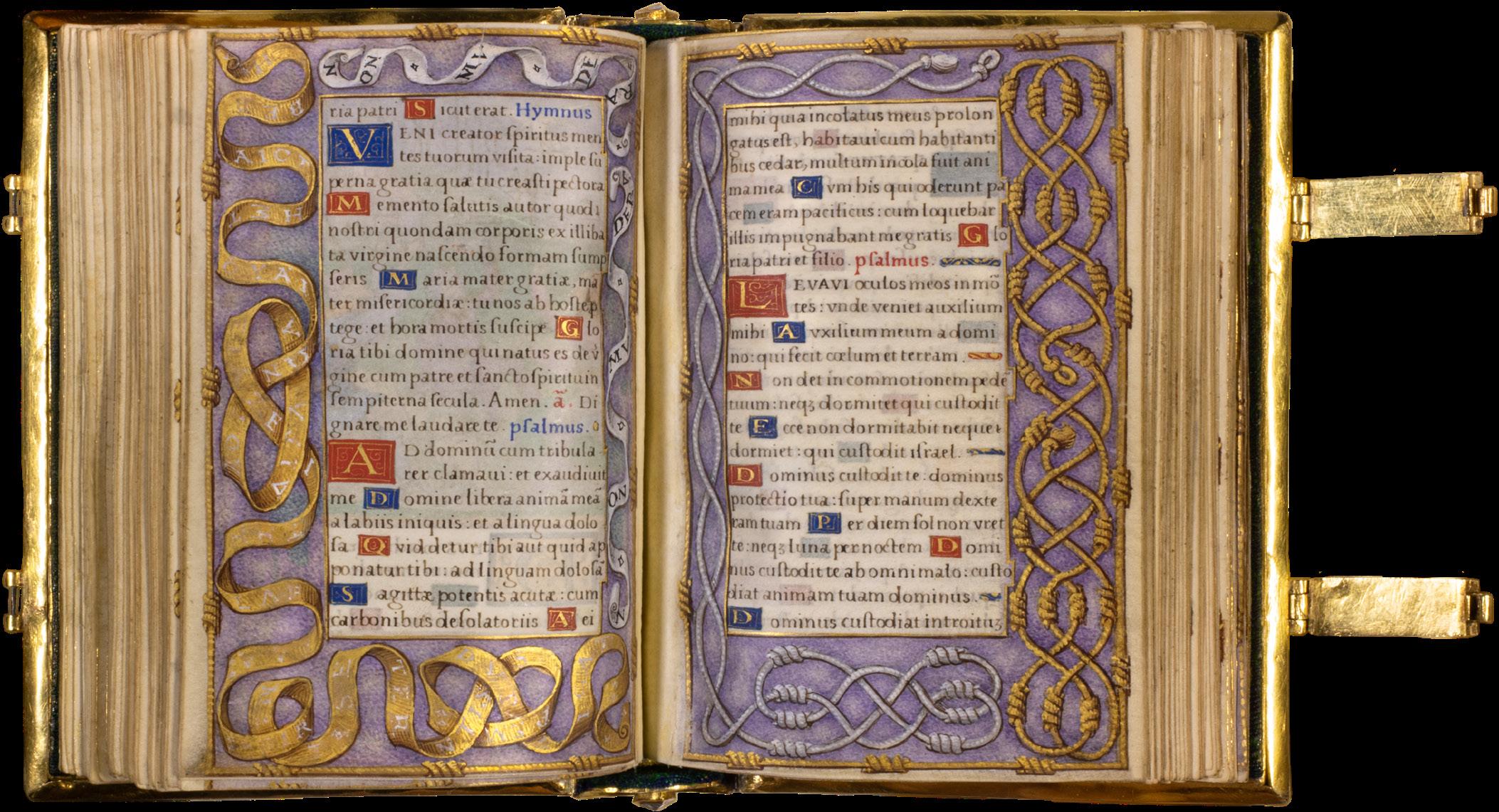

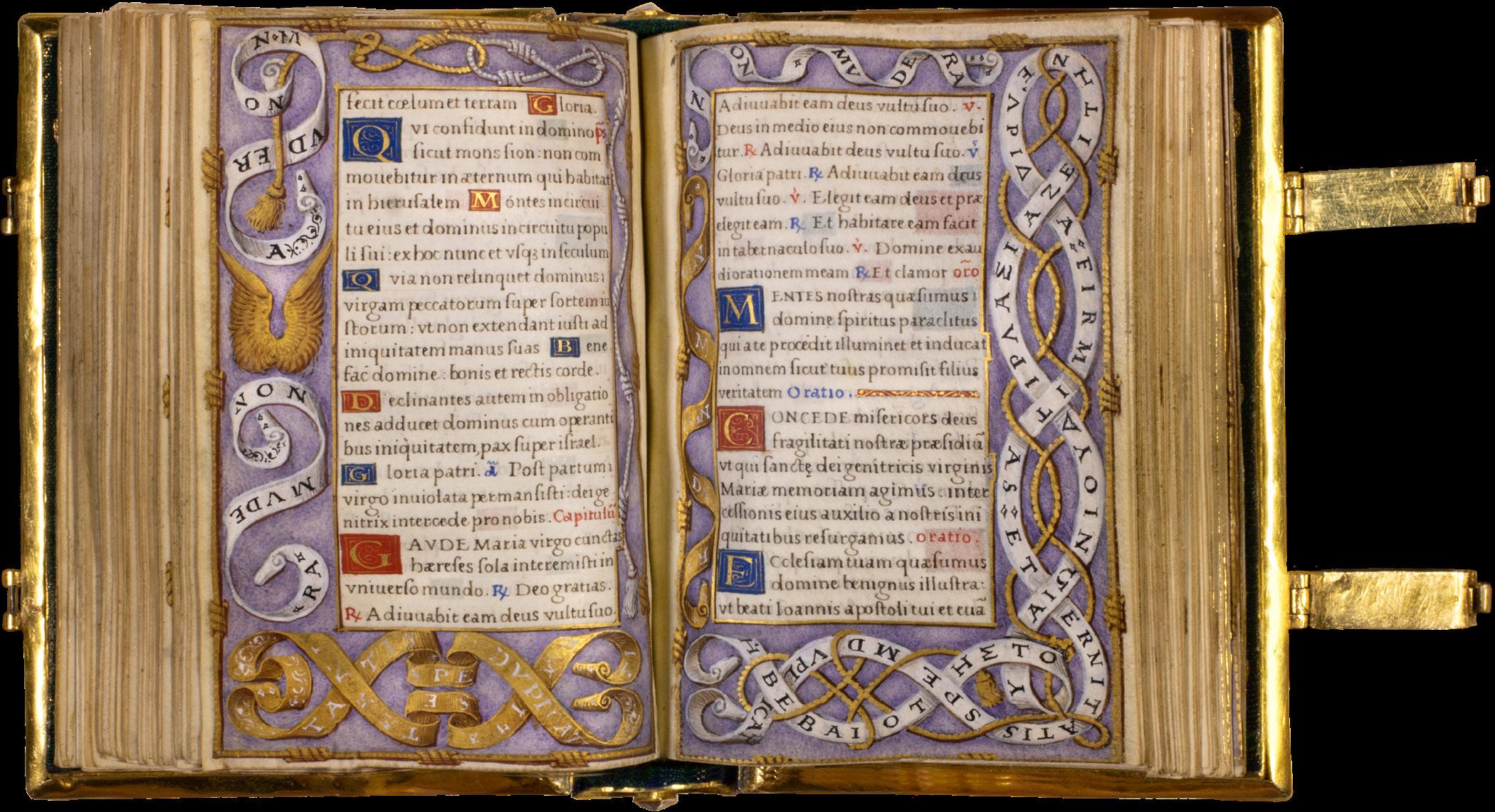

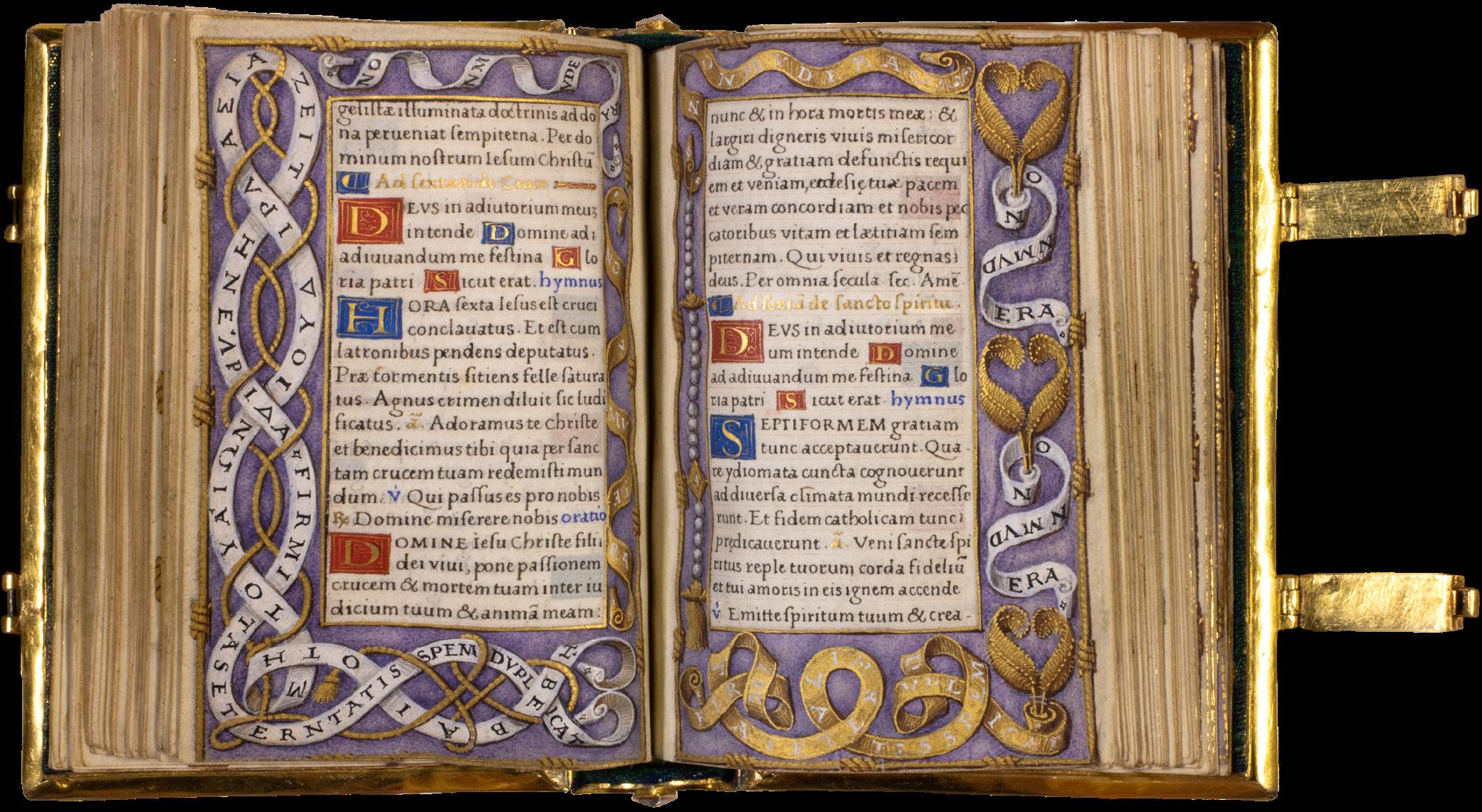

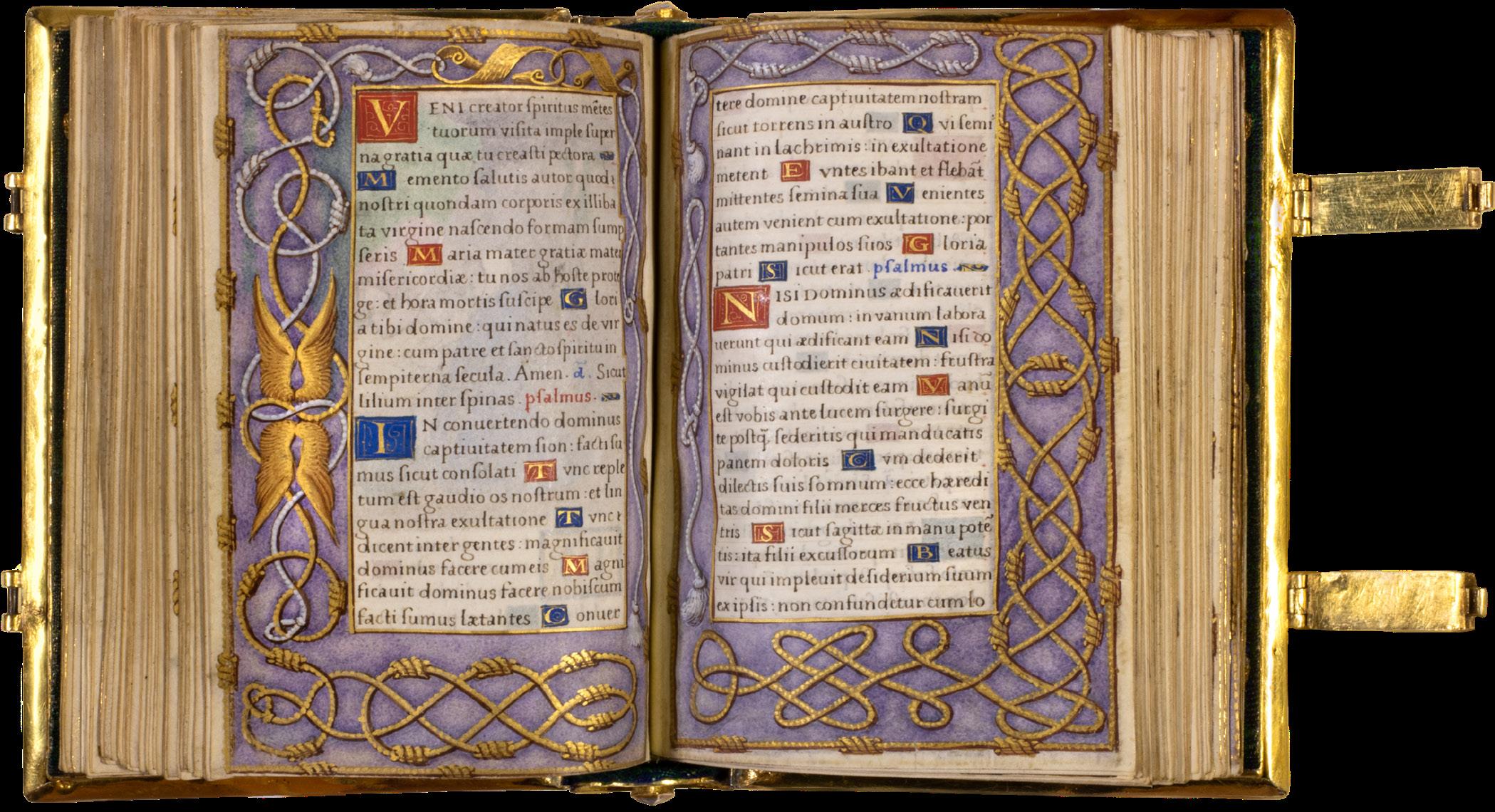

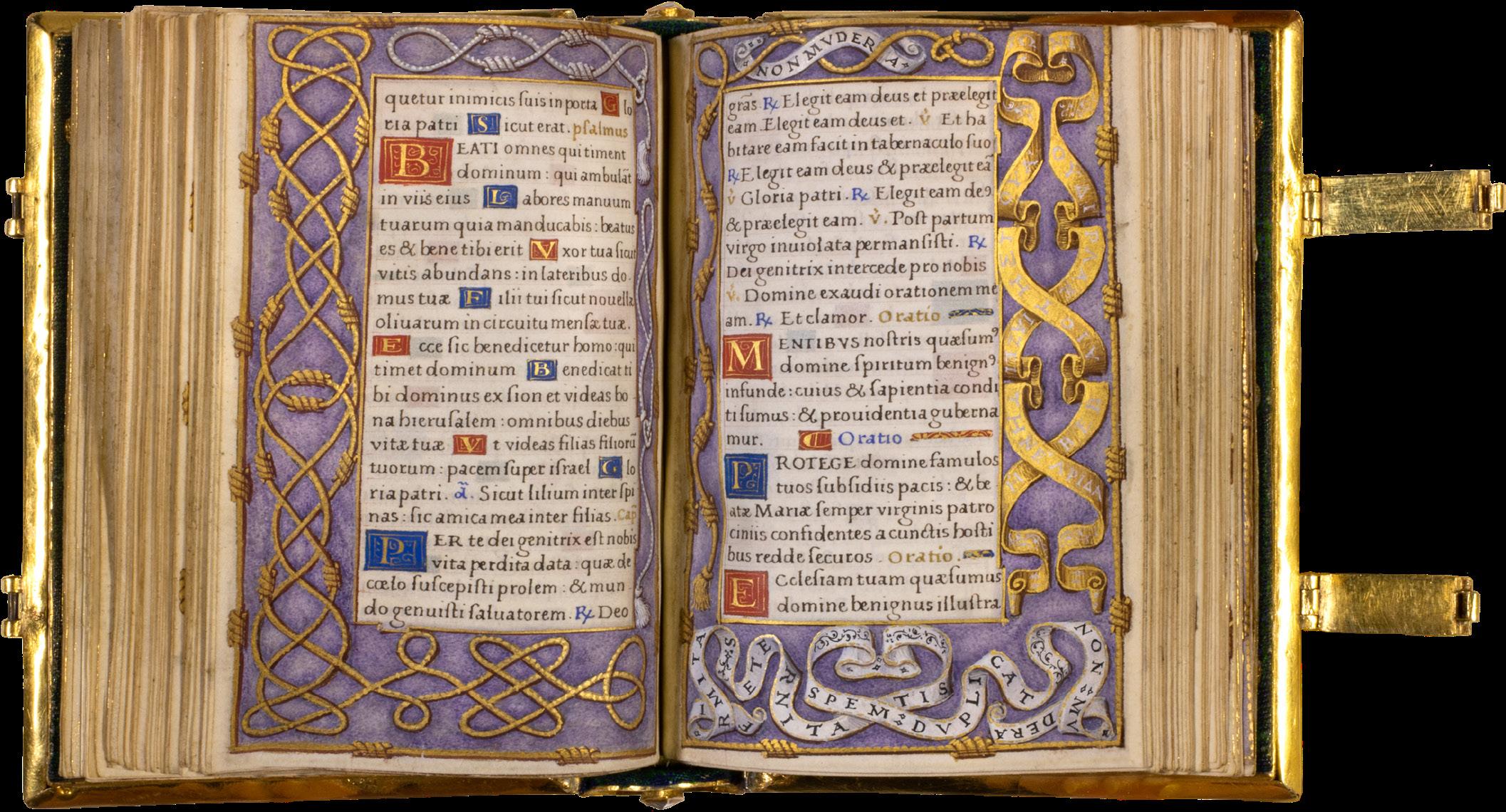

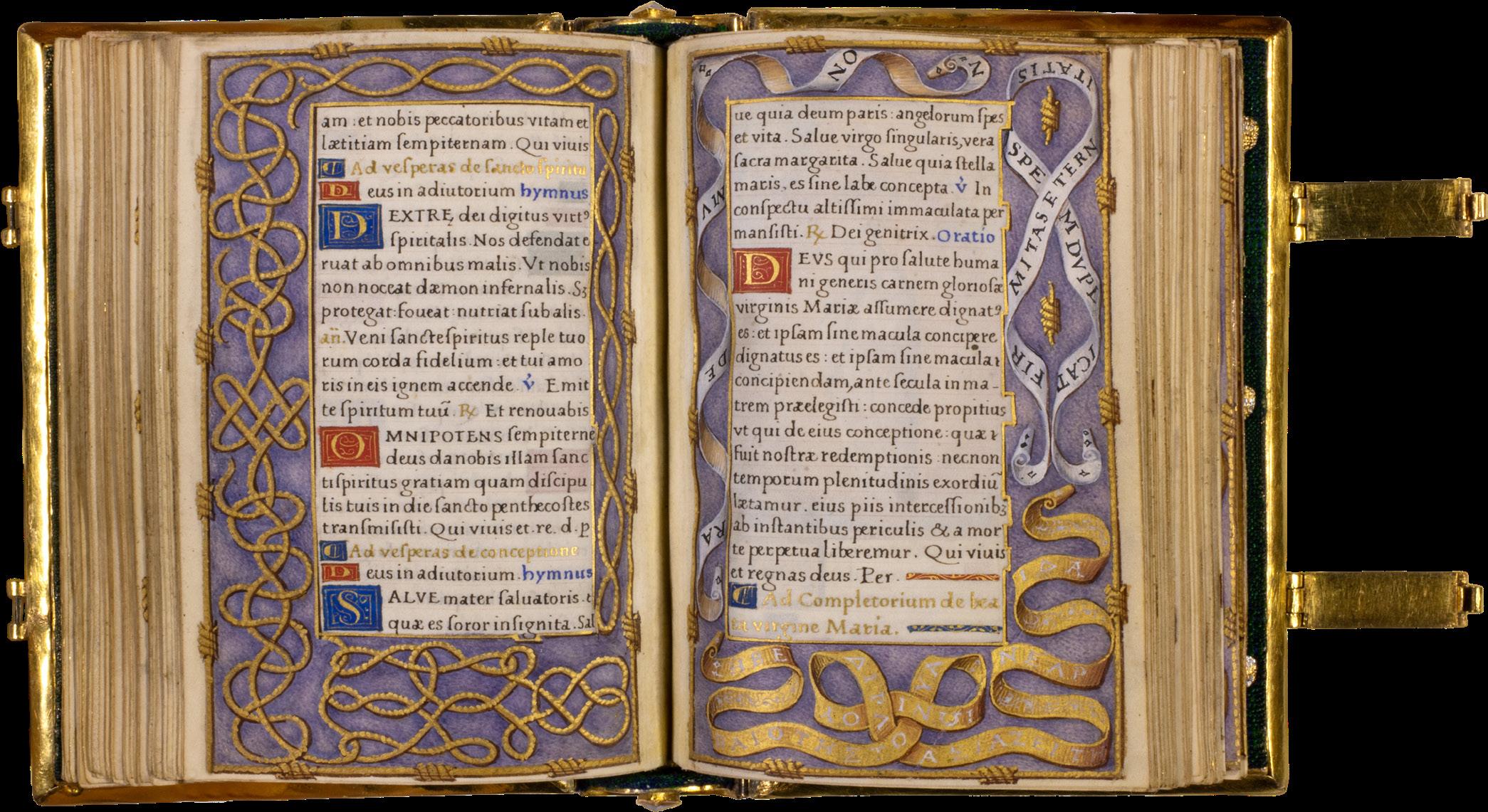

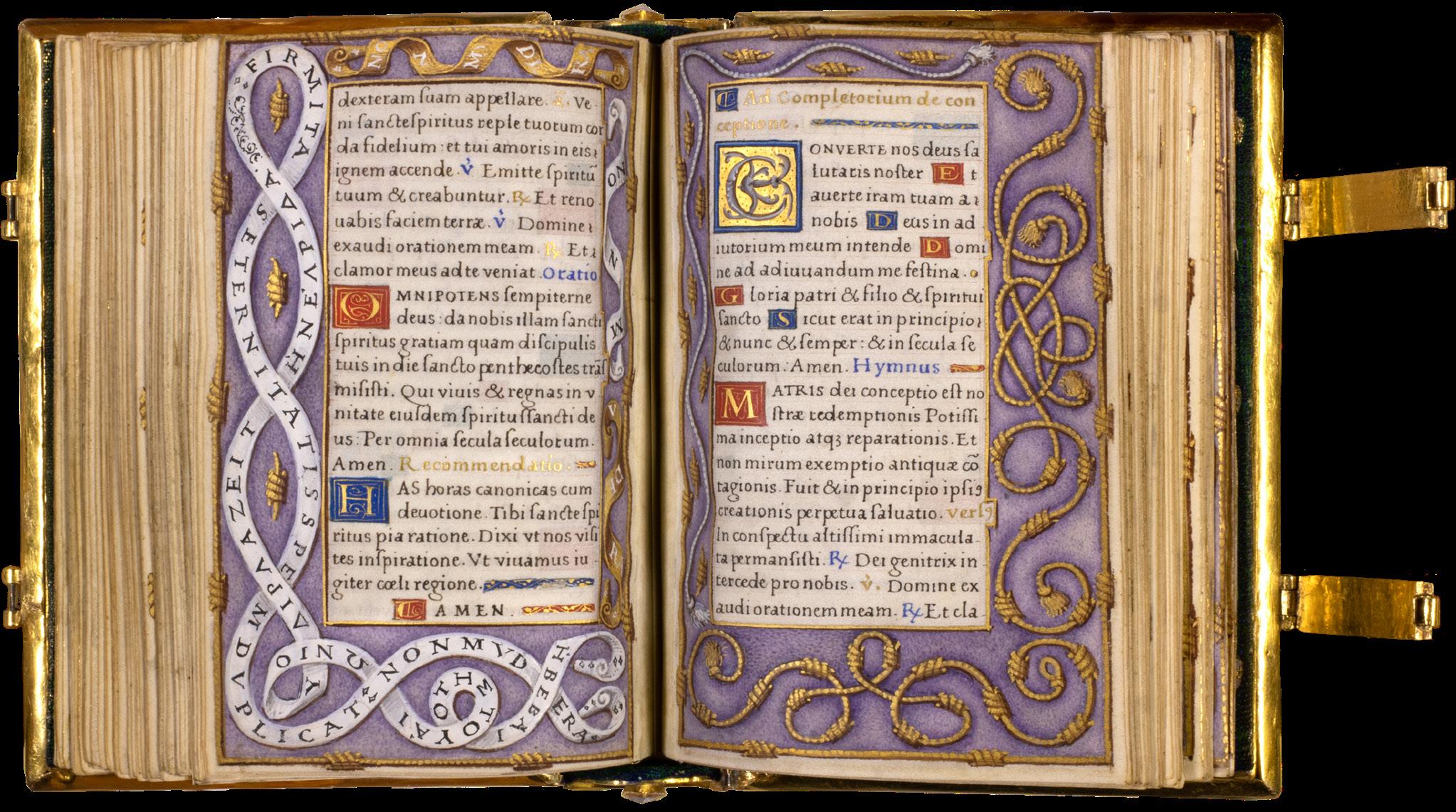

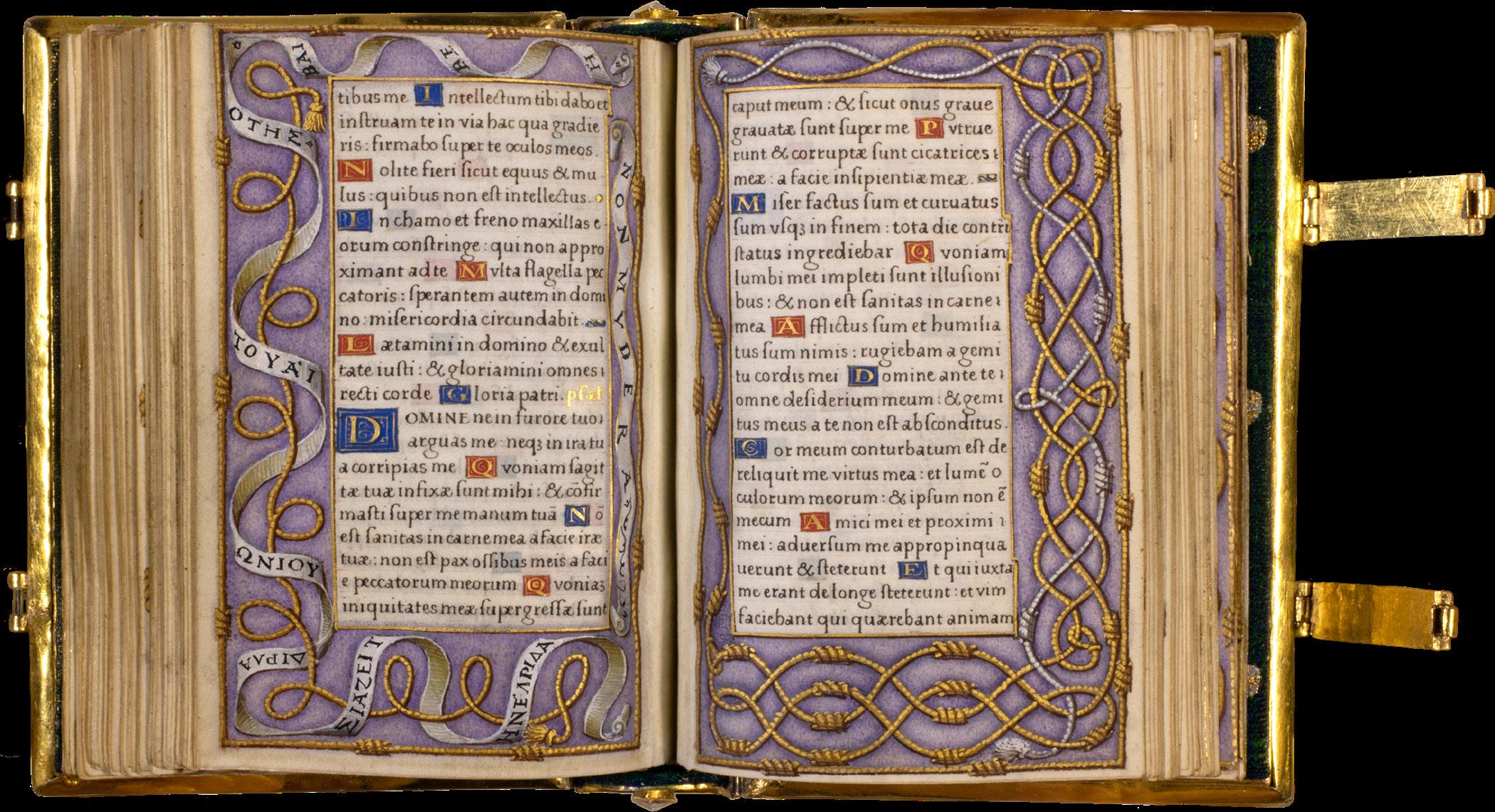

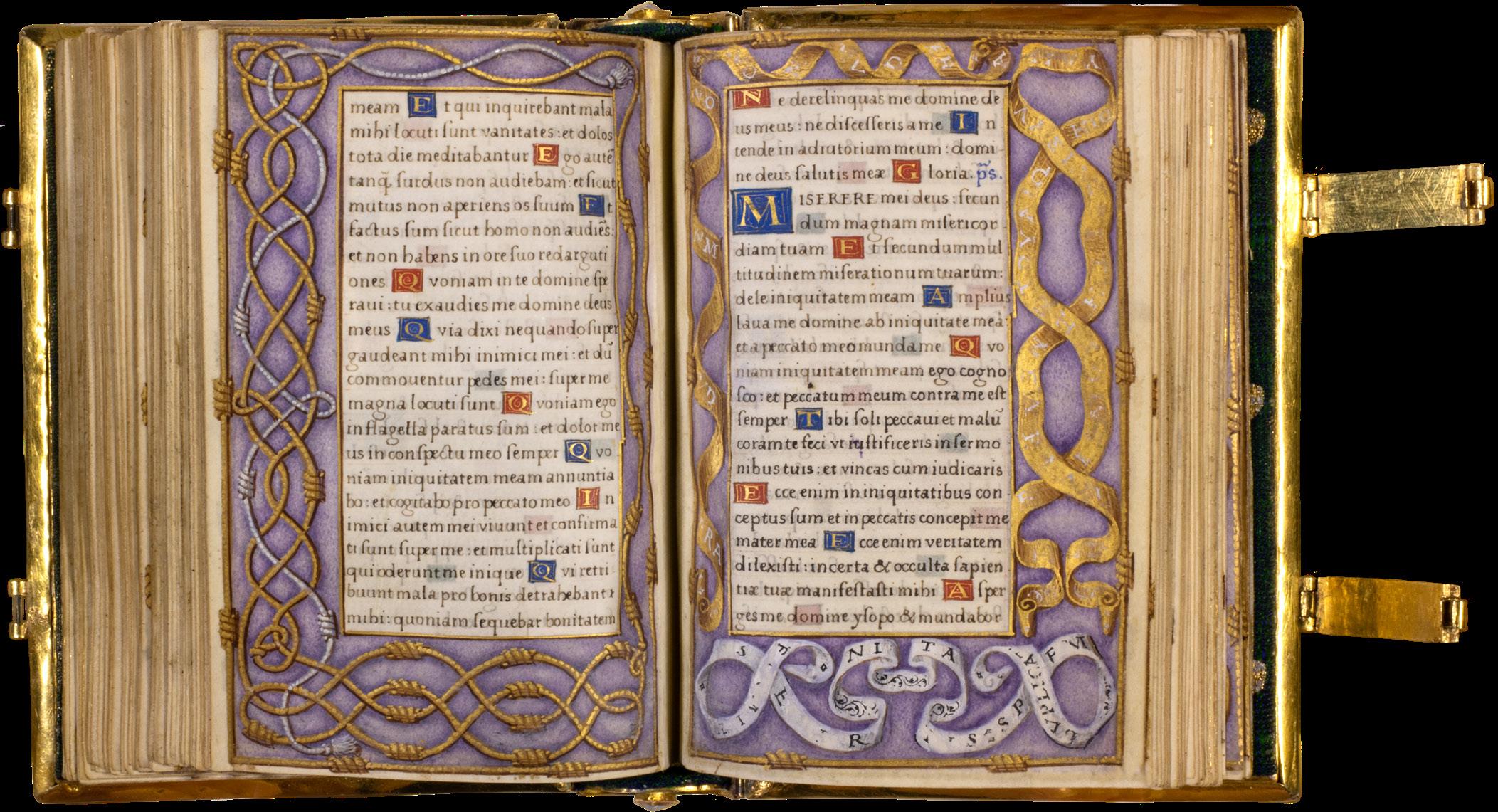

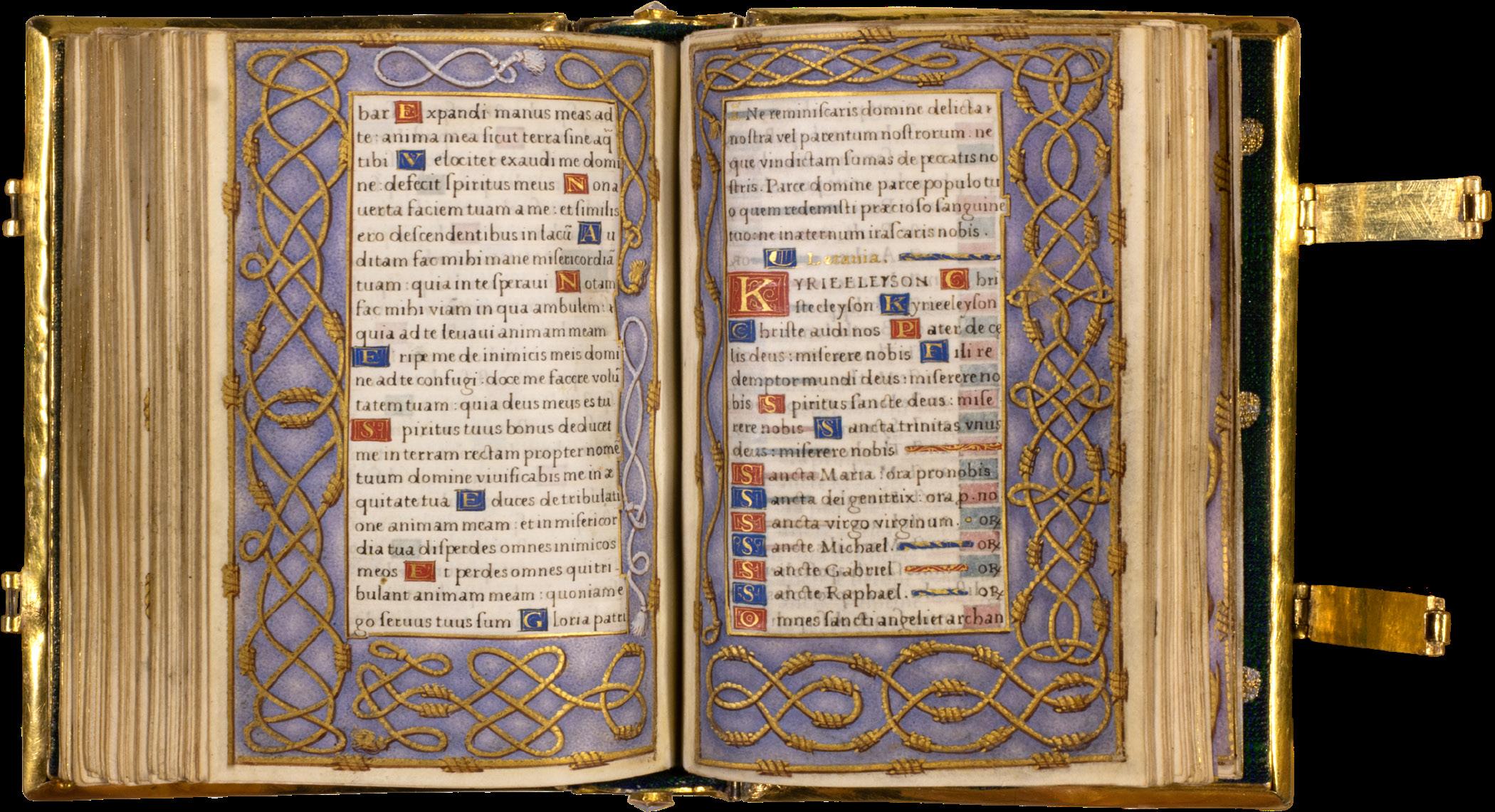

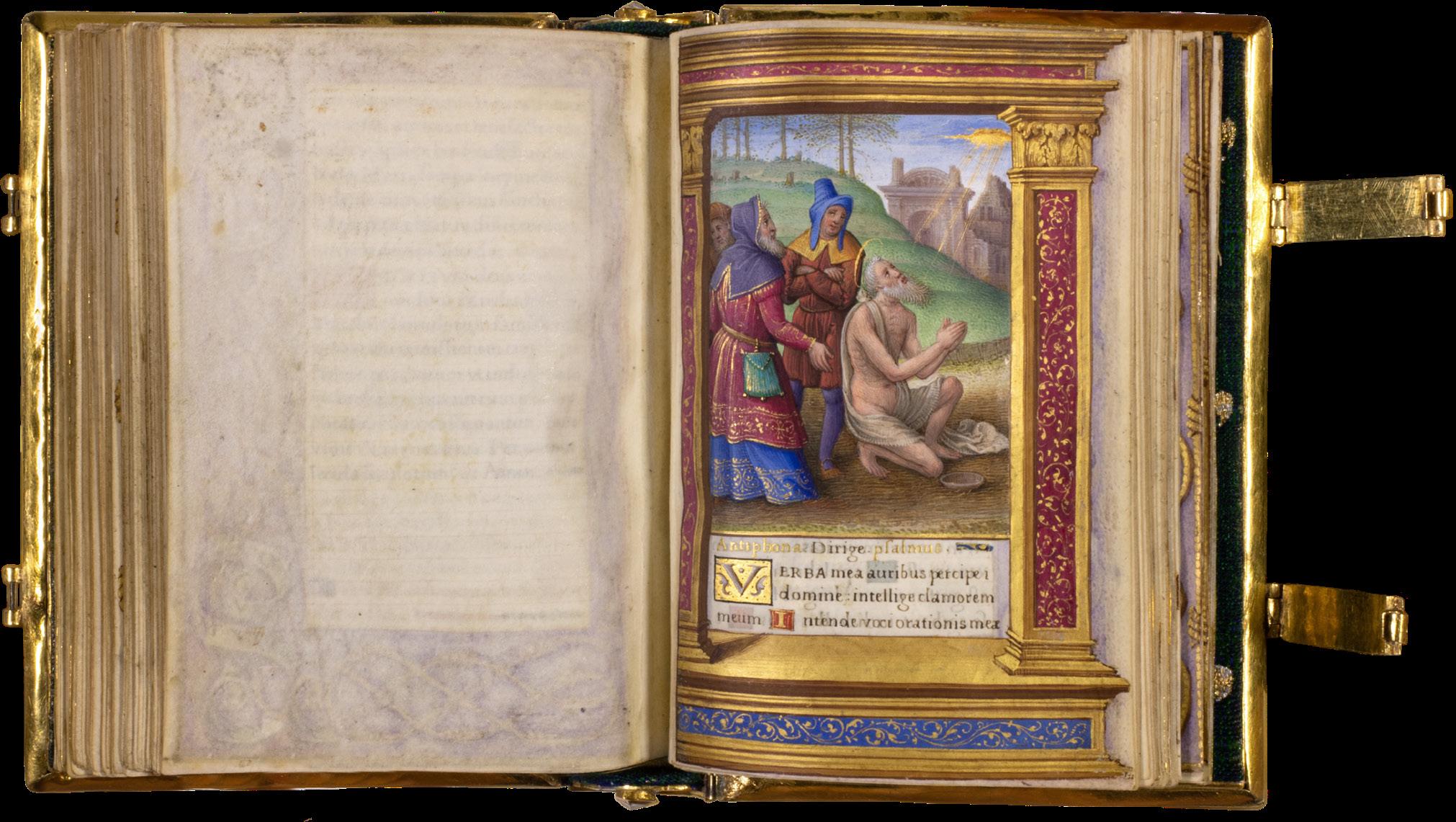

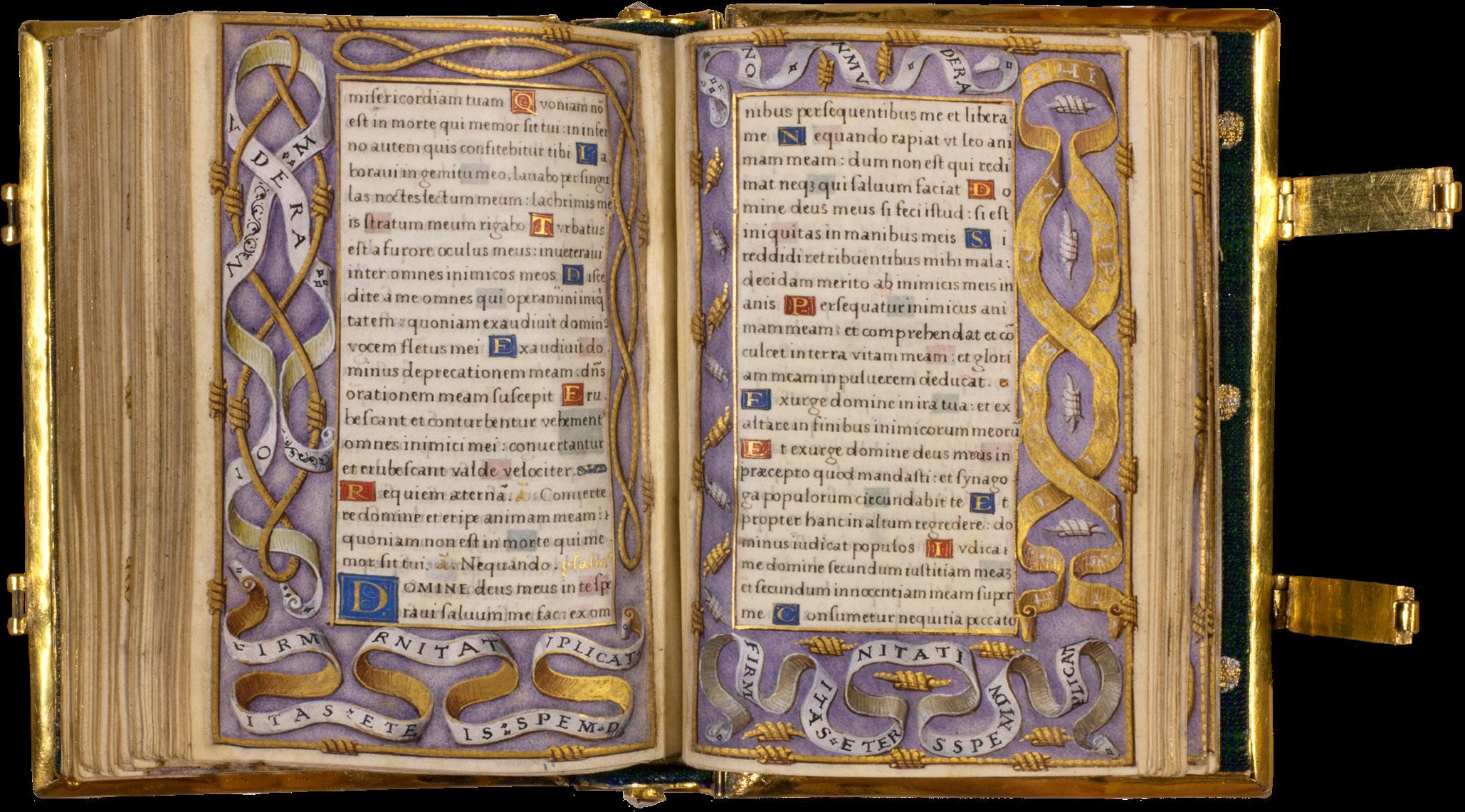

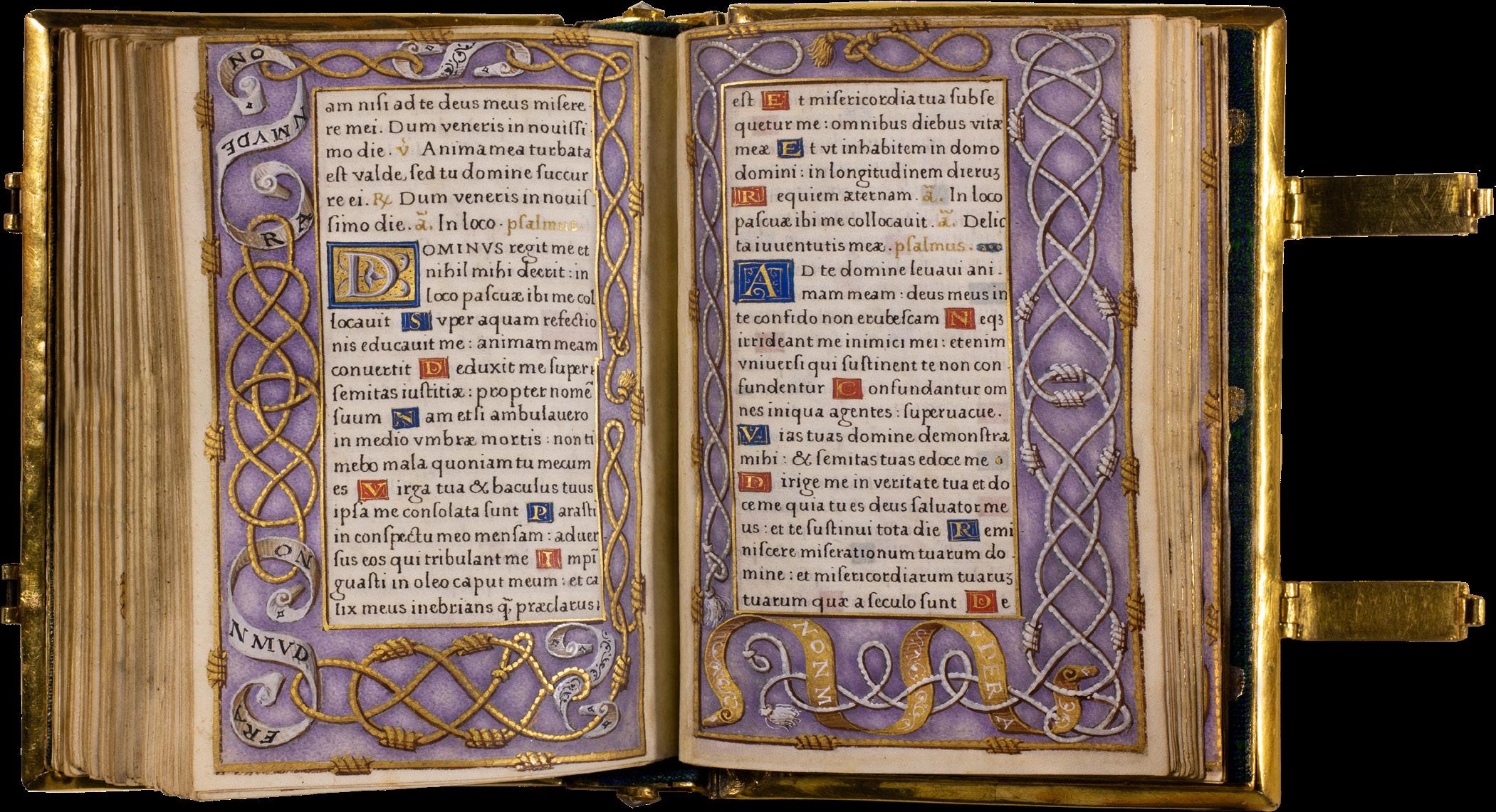

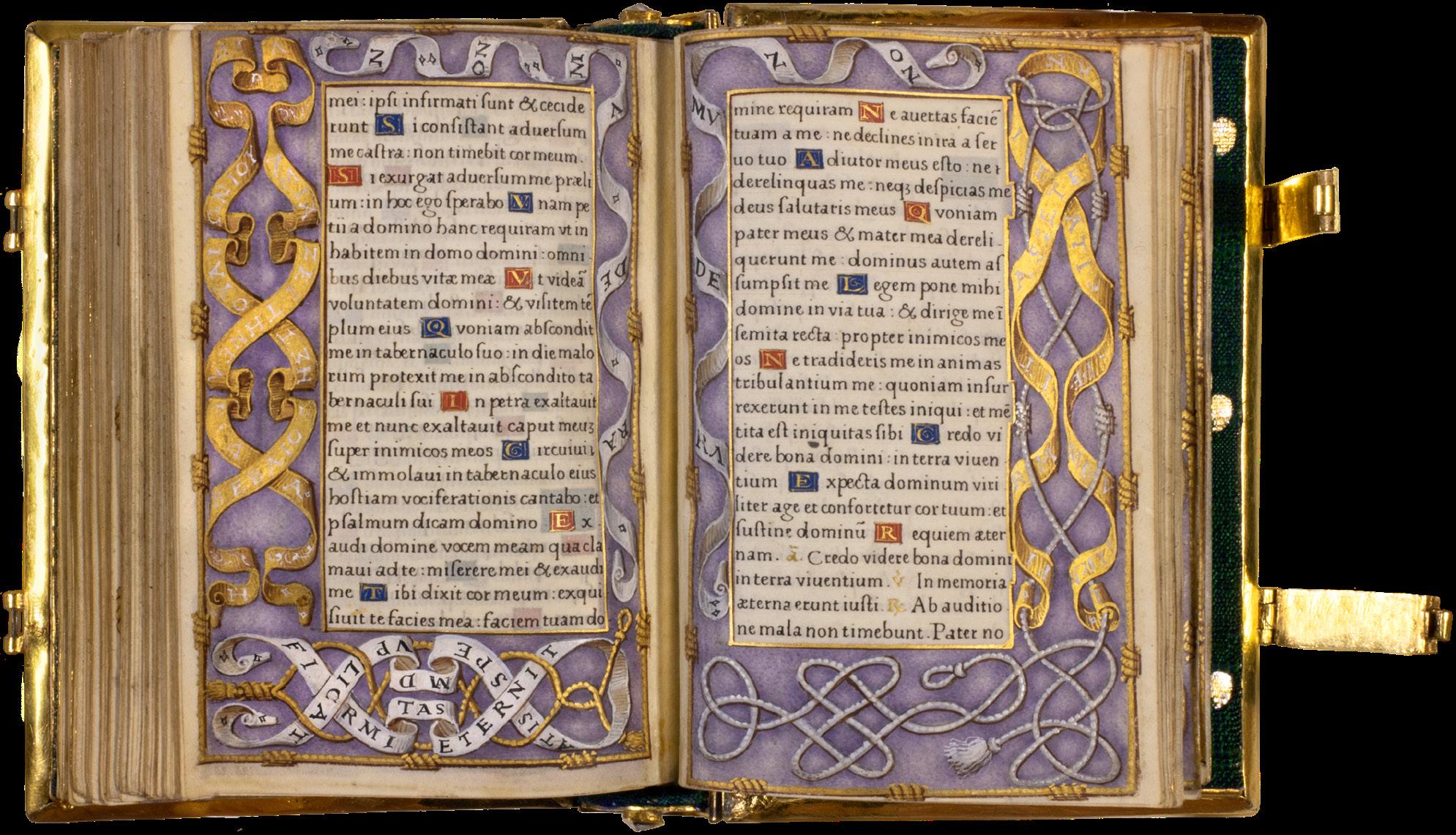

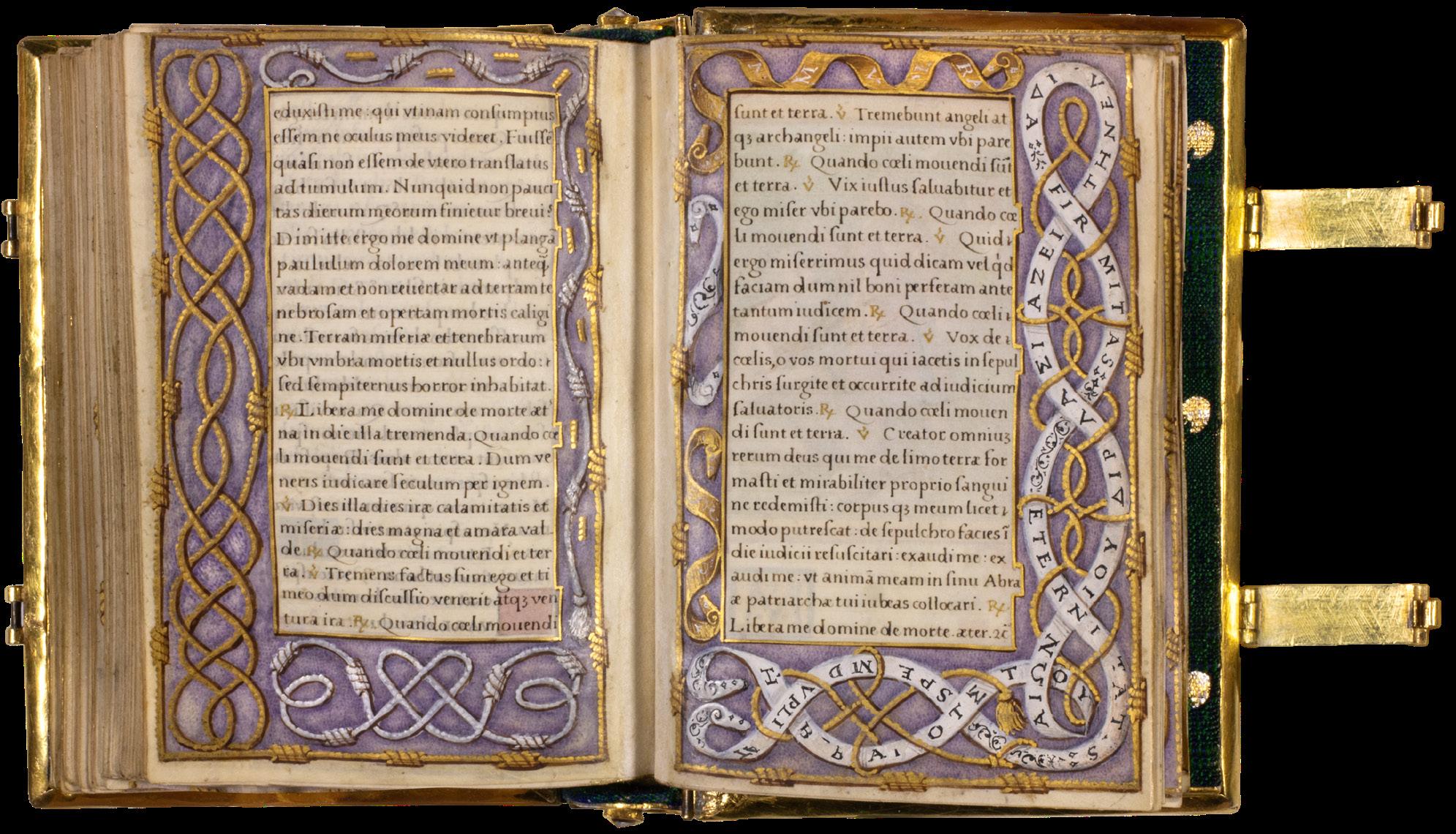

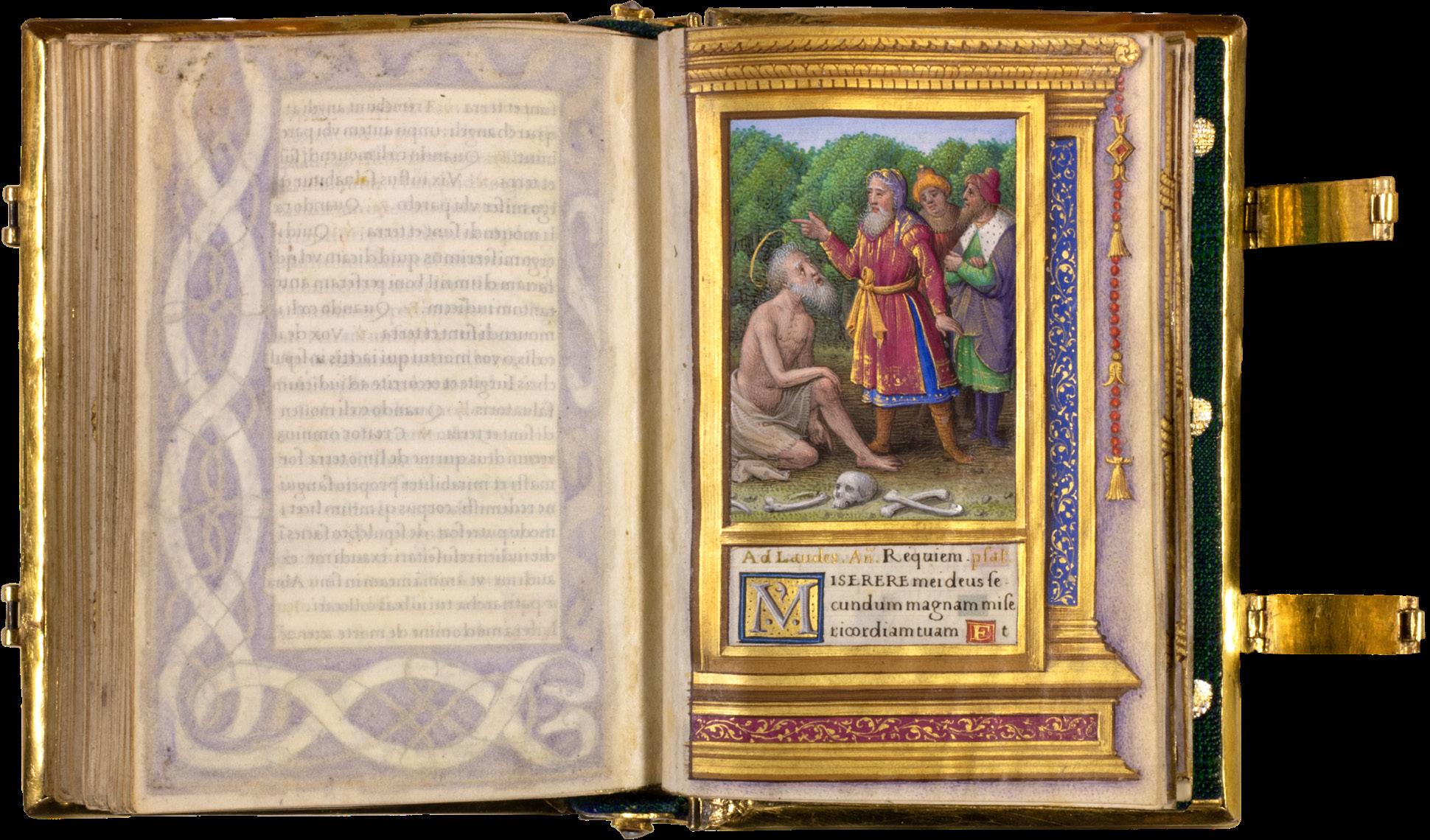

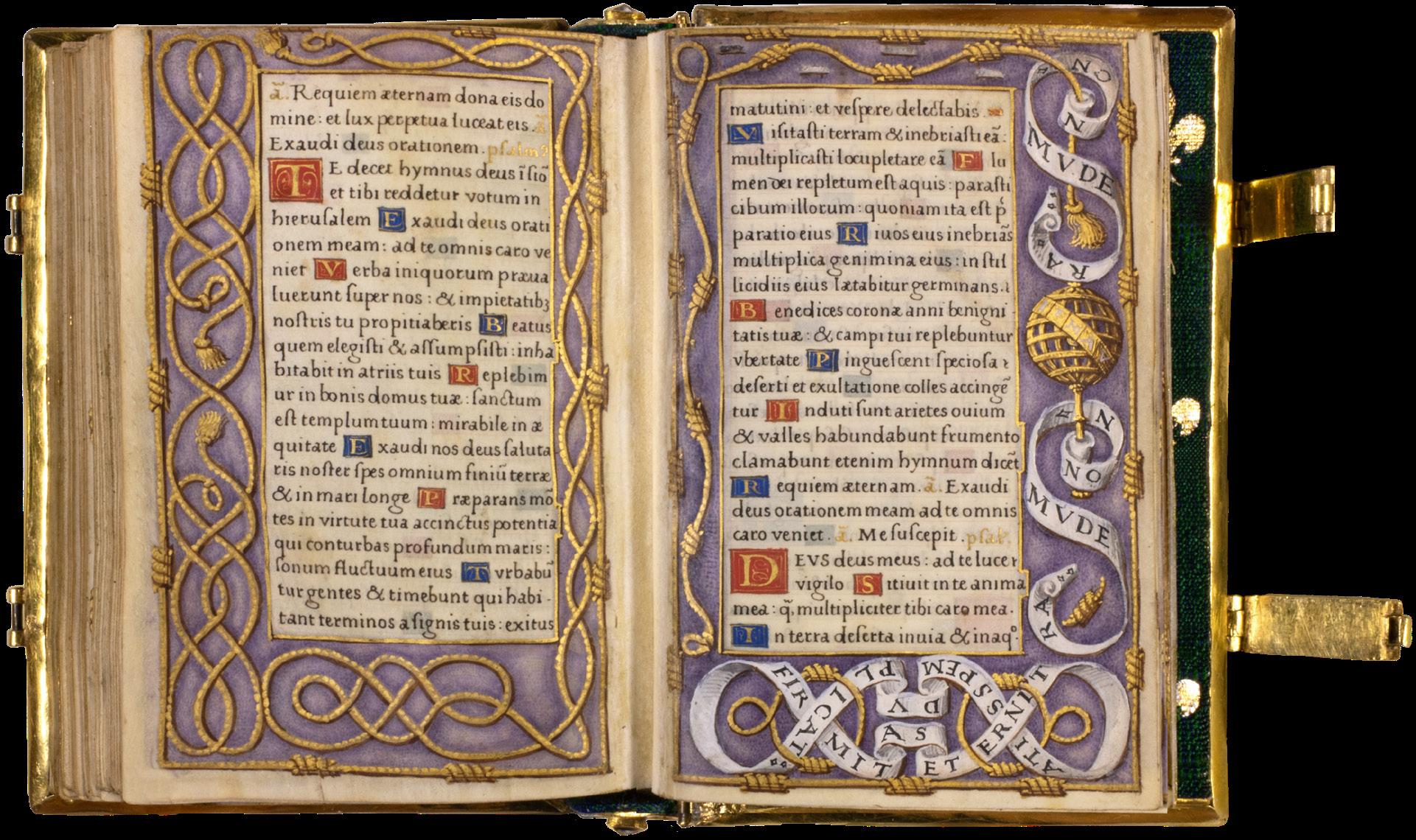

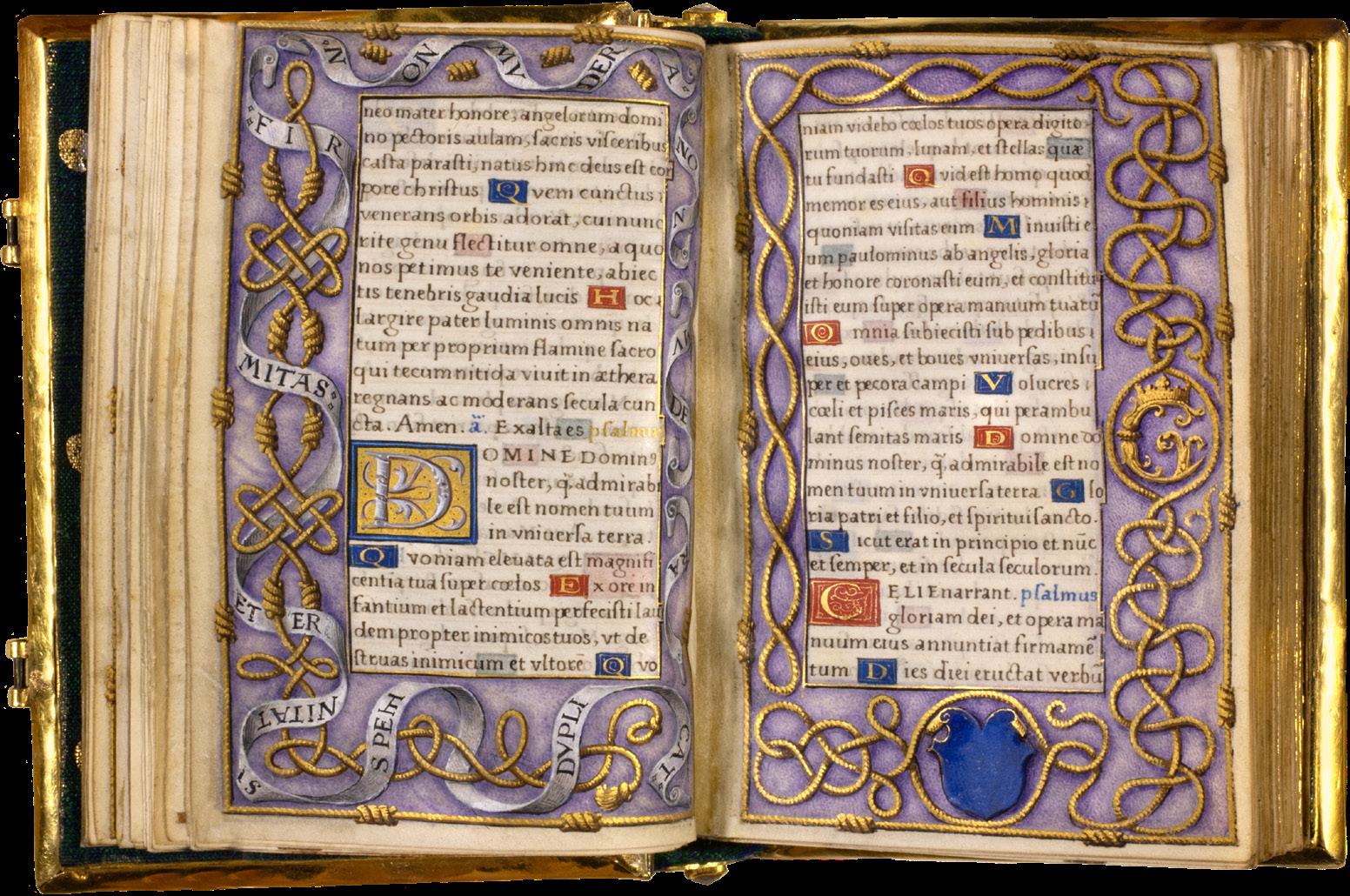

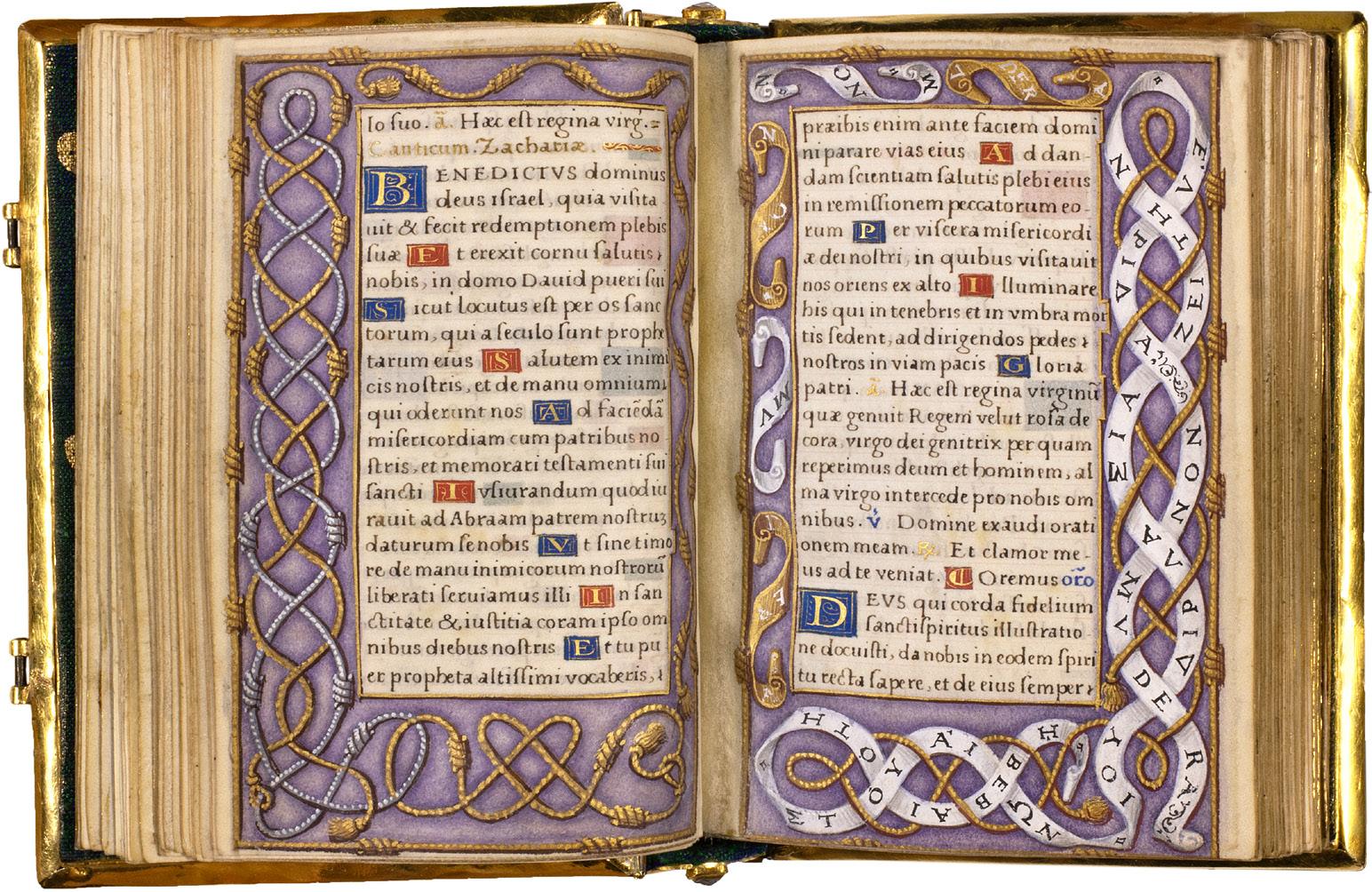

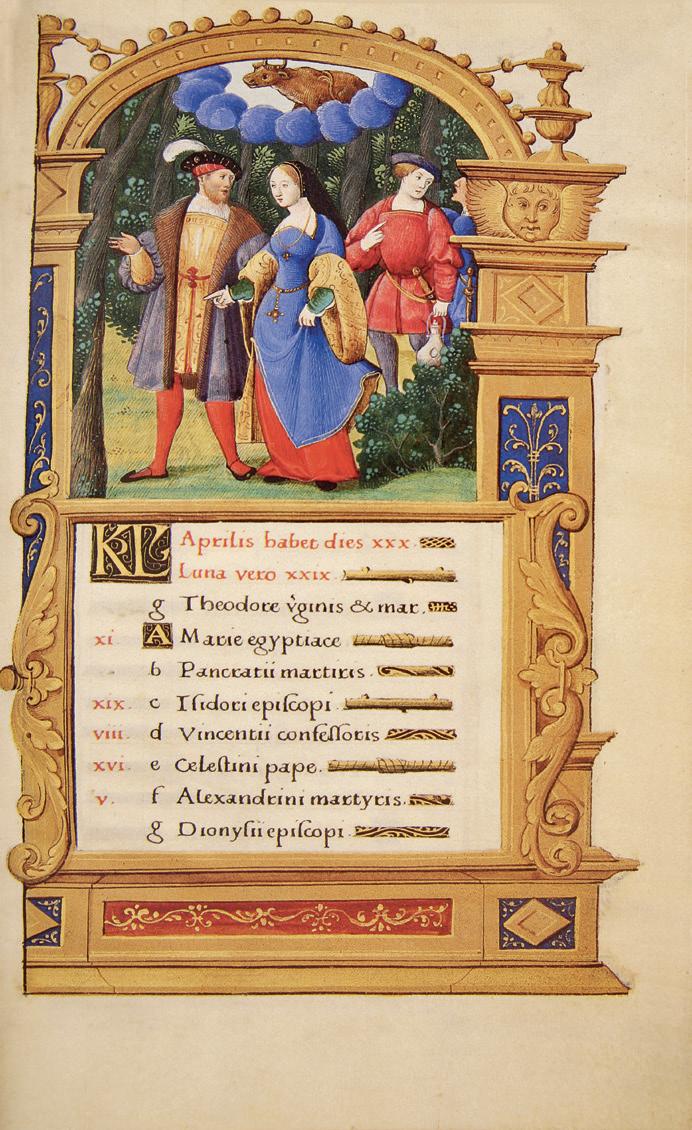

Whereas all miniature pages are framed with architectural Renaissance borders, the text pages including the calendar are framed with an elaborate system of references to Claude of France: motifs, which the queen adopted from her mother’s devices (the Spanish motto non mudera and the Franciscan cord) and more emblems such as Claude’s own motto in Latin and Greek, emblems of prudence (armillary sphere) and justice (ostrich feathers), as well as probable allusions to her father (wings – ailes in French – stand for the letter L) and to her mother-in-law Louise of Savoy (unknotted cord). The coloured ground of the border, lavender, can be interpreted as a reference to the amethyst and could point to the imperial ambitions of the French royal house since Charles VIII that also governed the foreign policy of Louis XII and Claude’s spouse, François Ier.

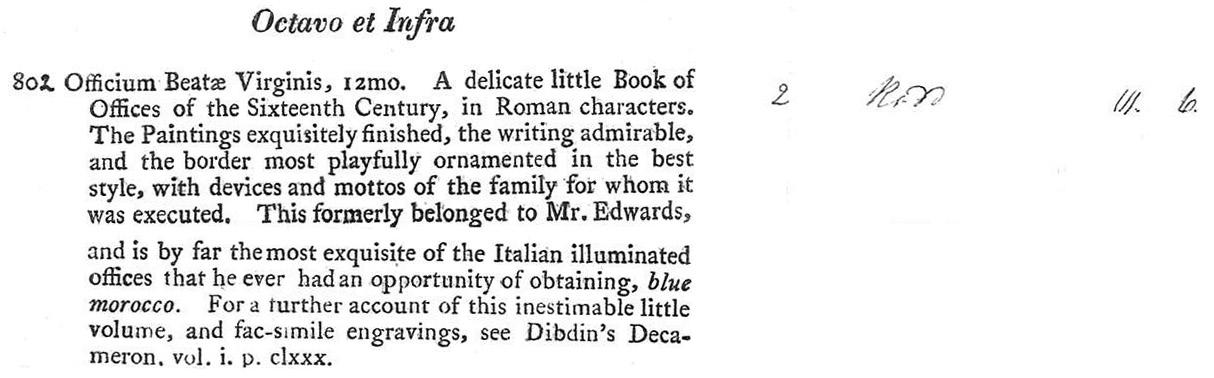

Although engravings of four calendar pages and the Assumpta of our manuscript, which was long thought to be of Italian origin, were published by Dibdin in 1817, it was not until 1975 that Charles Sterling published the Book of Hours, which was in the possession of the Rothschild family until 1968. Together with the even smaller fragment of a Book of Hours made for Claude of France known as her “prayer book” (M. 1166 at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York), it belongs to the core group of manuscripts that provide a basis for the identification of the Master of Claude of France.

The artist’s œuvre was since 1975 augmented by further attributions such as a primer for Claude’s sister Renée in Modena. Apparently, the Master of Claude of France worked together with Giovanni Todeschino and Jean Bourdichon on the Book of Hours made for King Frederick III of Aragon (Latin 1053 in Paris) before 1503. He stayed in Bourdichon’s workshop as an illuminator specialised in border decorations of various kinds and adapted Italian models imported by Todeschino, as well as the botanically orientated floral borders created by Bourdichon before 1508.

The Master of Claude of France seems to have painted his first miniatures only in the second decade of the sixteenth century. His brushwork and style contrast strongly with the style of Jean Bourdichon as well as with the style of Jean Poyer, both active in Tours, and it seems all the more likely that he trained with the Master of the della Rovere Missals (Jacques Ravauld or Ravaux?). This master would have acquainted him with Italian novelties and with the tradition of Jean Fouquet in Tours.

Sterling’s dating of our Book of Hours in the period before the coronation of Claude of France in 1517 influenced subsequent research, even if scholars have not always agreed with all of his arguments in detail. The fact that only pages with miniatures were available in reproduction distorted the evaluation of the manuscript: the distinct writing style and decoration of the Book of Hours allows a dating to the 1520s. This makes this unique manuscript the first prayer book in a minuscule format with larger line spacing that facilitated the readability of the small script considerably. In addition, the abstract concept of the borders reveals early Protestant tendencies at the French court, as Myra Orth has observed.

10

Only the dating as late as the 1520s does justice to the character of the splendid calendar pictures and the pictorial decoration, which is concentrated on the essentials. At the same time, the later dating of the manuscript would allow us to connect the Master of Claude of France with a certain Eloy Tassart, who has been recently discovered in documents from the court of the queen. He was active as the court illuminator of Claude of France in 1521 and 1523. This new finding indicates a dating of our Book of Hours to the final years of the short life of Queen Claude, who already died in July 1524.

4

The intellectual severity of the manuscript represents a crucial moment in the history of the prayer book: still fundamentally rooted in the late medieval tradition of Books of Hours, the manuscript made for Claude of France dismisses important elements, such as the prayers to the Virgin and the cult of saints, as well as the triumphant propensity for images, which still rules the decoration of the New York prayer book. Both the scribe and the illuminator processed different impulses from Italy, among them the ostrich feathers as a personal device of the magnificent Lorenzo de’ Medici.

Our manuscript is the very point of departure for the definition of the Master of Claude of France, who might be identified with Eloy Tassart. In its new golden binding made in the imperial Prague of Rudolph II, this treasure, which combines magnificent enamel work and diamonds with ravishing book art in script, decoration and miniatures of the monthly occupations as well as the most important events of the New Testament, represents two outstanding apogees from the late phase of the handwritten book. It embodies the French Renaissance, which adopted the greatest achievements of Flemish and Italian art as its own, and is triumphantly linked to the imperial splendour on the eve of the Thirty Year’s War.

11

tH e book of Hours of claude de france and H er M aster eloy tassart

A Treasure for Prayer

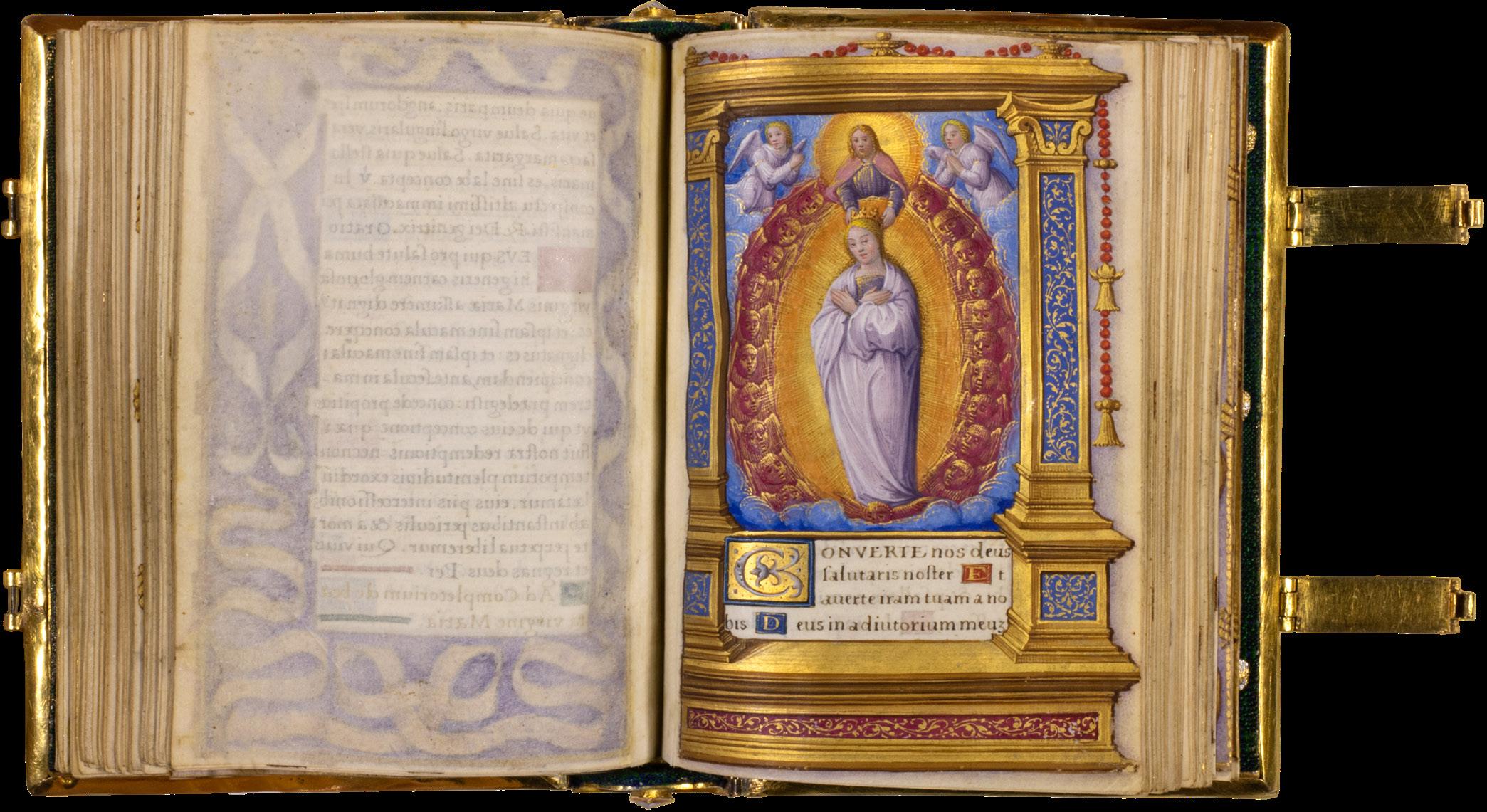

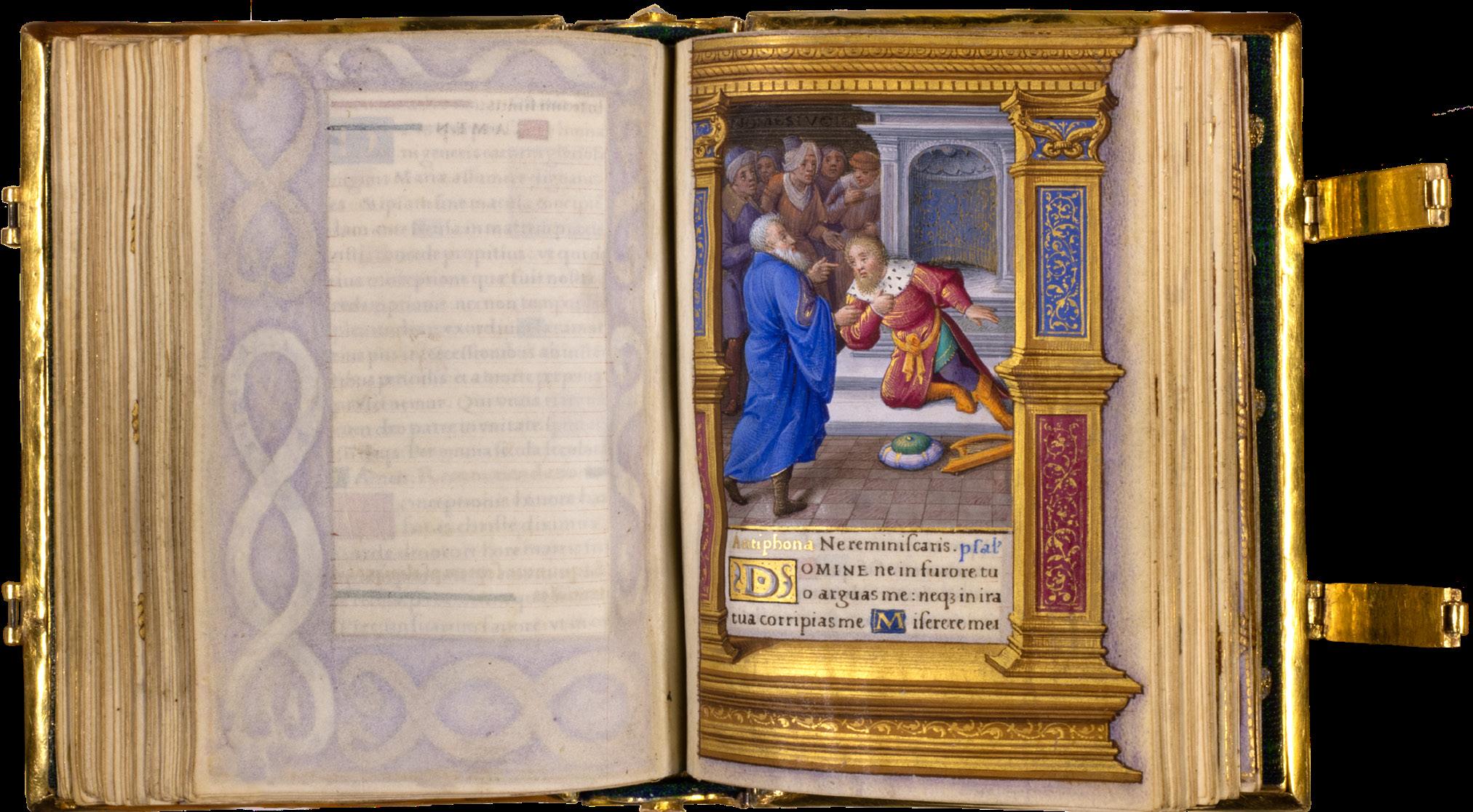

Whoever looks at or even has the privilege of holding the manuscript this publication is dedicated to will not believe his or her eyes; this treasure sparkles in its golden binding, set with precious stones, as if it had been made especially for the sumptuous little book it contains today. What would Reverend Dibdin have said if he ever had seen the manuscript in its present state? He knew it quite well even though he did not know about its patron; he thought it was of Italian origin and honoured it with five engraved reproductions in original size. Four reproduce calendar pages and only one other represents an ultra-catholic theme, Maria Assumpta, who is raised above the heavens to be crowned in glory.1

Yet the manuscript and its binding were not made at the same time and place – as usually is the case – but epitomise nonetheless, even whilst being separated by almost a century, the same court culture of the Northern Renaissance. In France, it flourished in an atmosphere open to Italian and Flemish influences that – in the eyes of historians over the last two centuries – led to the suppression of any true French originality. This Renaissance, slowly merging

into Mannerism and early Baroque, reached its last unforeseen peak in southern Germany and above all in Bohemian Prague during the reign of Emperor Rudolph II. The manuscript is thus a product of French culture around 1500 whilst the binding is a masterpiece of southern German craftsmanship in Bohemia around 1600.

A Lucky Coincidence

In recent times an antiquarian joined the binding and the precious book, after the original appearance of the manuscript had been altered in the nineteenth century. It is not known how the manuscript was bound when it arrived in England at an unknown date, but officious concern for its state of preservation instead damaged the book’s condition. The very small format measuring just about 84 by 61 millimetres made the 122 leaves of the most delicate parchment, which were cropped from the very beginning just along the edge of the border decoration, extremely difficult to leaf through.

This compromised the preservation of the illuminated margins and, motivated by the fear of losing the exquisite border decorations due to rubbing against the opposite pages, the book was reset and rebound with paper interleaves, placed

13

between the individual leaves. The original collation was destroyed as a consequence of the rebinding the manuscript, and at the same time the aesthetic impact of the spreads, especially of the exquisite text pages with their uniquely illuminated borders, was no longer visible. Since the paper leaves were larger than the original folios, the pages of the newly bound manuscript could now be turned without touching the parchment. Despite this advantage for the handling of the book, the nineteenth-century intervention turned out to have caused more danger to the manuscript than imagined: After more than a century, the illuminations left minor stains on the paper interleaves, which, as carefully selected as they might have been, always react more receptively to manuscript paint than parchment usually tends to do. Fortunately, no major damage was caused, but the manuscript could not have been preserved in the perilous condition it was found in when it last changed owners.

In preparation of the recent rebinding by James Brockman, the original parchment components of the manuscript were separated from the rest and since the old collation was destroyed, it was advisable to add a few millimetres of parchment to the inner margins towards the gutter to ensure that the book is easy to open and its pages can be easily turned. The blue nineteenth-century stamped and gilded morocco binding and the dentelle of the endpapers as well as the paper

leaves covered with darkened adhesive and slight imprints of the metallic pigments used to paint the illuminated borders are preserved.

The codex is now covered with a very rare and precious golden binding, which ennobles the exquisite manuscript hidden within. Even if this binding was not specifically made for this particular Book of Hours, it once covered a comparable book, which is today lost or can no longer be identified. Today, an unexpected coincidence has joined an outstanding work of goldsmithery

14

Hours of Claude of France: binding

that has long lost the content it was made for and a ravishingly beautiful manuscript, which fits its new shell perfectly – the decision to put both together follows a line often encountered in the history of precious books. The manuscript is today much better preserved without the paper leaves, which reacted to the precious metal colours, and its binding is no longer just a pure adornment but serves yet again its intended purpose.

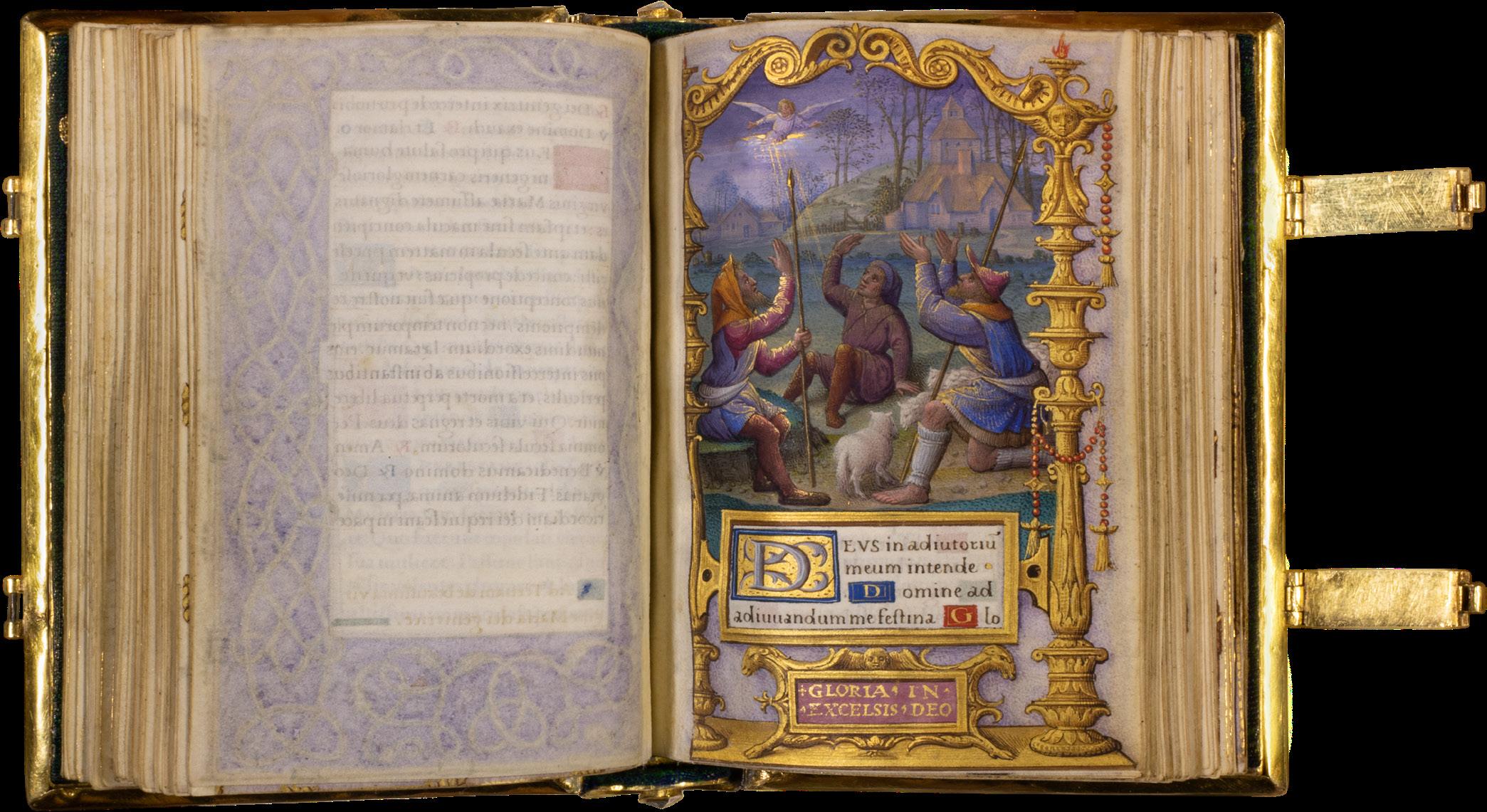

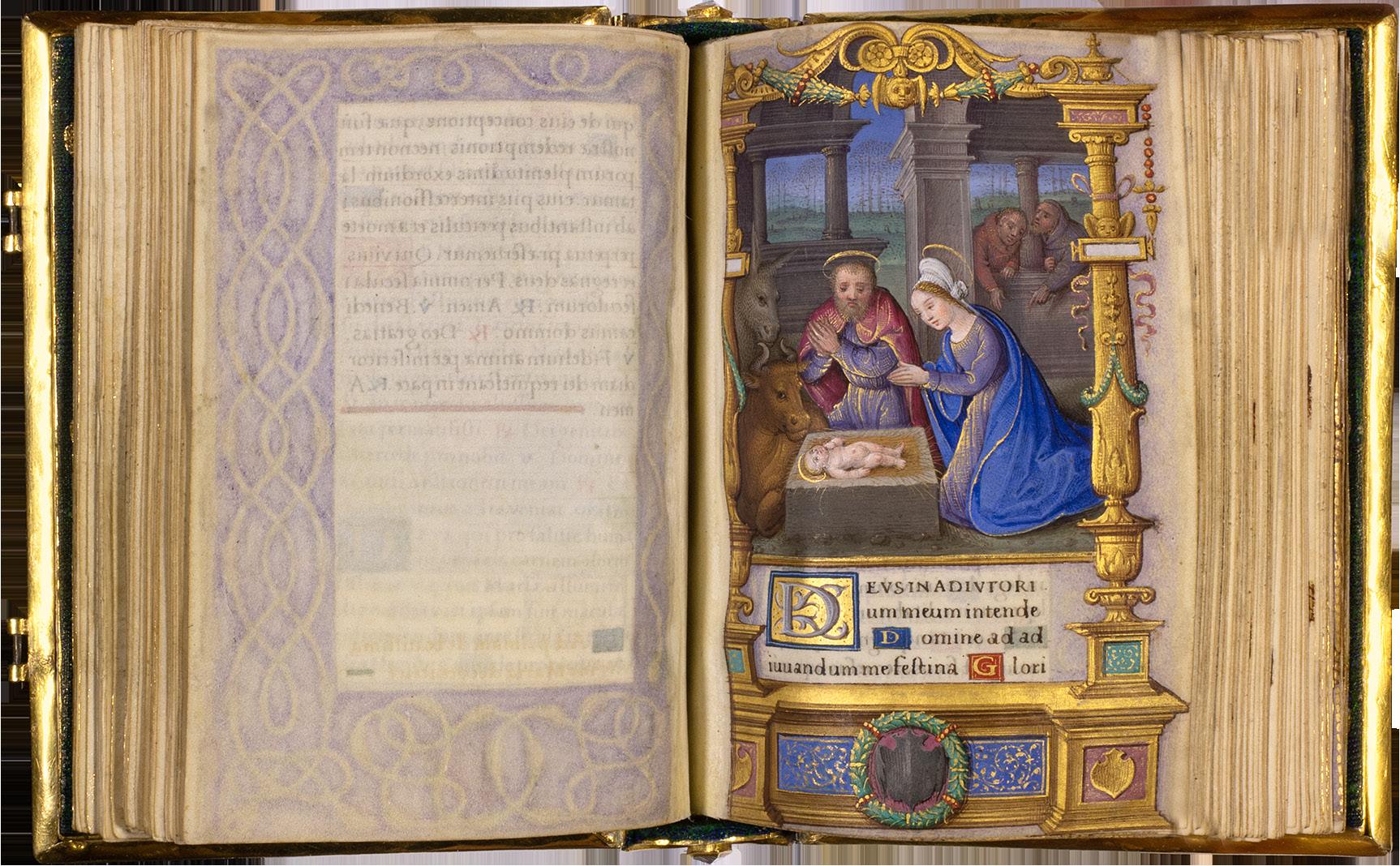

Christian High Feasts and the Passion

The Adoration of the Child is emblazoned on the front cover of this sixteenth-century binding: Under the ruinous rafter of the stable in Bethlehem the Virgin Mary has bedded the naked newborn in a low plaited crib surrounded by shepherds who have gathered around the Mother of God to adore the Saviour. Magnificent blossoms are laid out around the oval medallion and reappear on the back cover, where they seem even more brilliant. There, they surround an image of Easter morning: The Saviour emerges from a grey stone casket that had served as his sarcophagus and stands triumphantly with the elevated cross banner and a flapping blue (not the usual red) mantle against the sky. Three soldiers surround the sarcophagus; one is still asleep, the second raises his shield to protect himself clumsily from the apparition and the third tries to escape to the right. The cover medallions of the binding thus

splendidly unite the two highest feasts of the Western Church.

Even the binding’s spine celebrates redemption: Diamonds are inserted in all four fields on the spine, each one marking the crossing point of elongated objects that signify the Arma Christi, the instruments of his martyrdom. The bars cross and form the shape of an X, whereas the remaining triangles are filled with elements that fit their form. This dense depiction seems almost even more astonishing than both medallions on the covers and the ornamental predisposition underlines the cultural affiliation with the illuminated borders in the newly bound manuscript. All motives can be read in a clearly intended but not fully consistent chronological order from the bottom to the top. The point of departure is the Arrest of Christ and the Judgement of Pilate: the sparkling gold of the bowl and the can he used to wash his hands in innocence are shown and above them the henchmen’s thrust weapons cross, accompanied by a scimitar. The unsewn garment of Christ fills the field above, followed by a crossed halberd and ladder together with Malchus’ lamp; an iron glove and Stephaton’s pot of vinegar are placed on the lateral edges whereas the centre is adorned with the green crown of thorns. The column of the Flagellation then crosses with the spear of Longinus; the faggots at the edges relate to the Flagellation as well as the

15

scourge with three metal stars. The three dice, which were used to gamble for the garment of Christ, lie at the bottom and the three nails with which the Saviour was nailed to the cross are pinned behind the diamond. From the Chalice of Suffering to the Denial of Saint Peter the events are reflected once again; the lance with the sponge of vinegar and a cross without an inscription meet here, and the hammer forging the nails is placed in the corner to the right. The significance of the blue ribbons that fill the ground of all the fields is clear by now: those are the ropes that were uses to tie down Christ.

The binding thus follows an ancient Christian tradition that valued all traces of the Passion of the Saviour and especially the Arma Christi as divine treasures given to mankind. This view also explains the necessity to embellish not just reliquaries that almost exclusively testify of suffering and death but also the images of suffering themselves with splendorous materials. Despite their use as instruments of torture, the Arma Christi were venerated as an invaluably precious heritage and the covers of the gilded binding show the two most important events of the Good Tiding: the Incarnation of the Saviour on Christmas Eve and his Resurrection in the Easter vigil.

Prayer Books between Library and Treasury

One might ask if an object that like our gem consists of a French Book of Hours and a Bohe-

mian gold work binding did not belong to a treasury or a library. A short historical review might help for orientation: what we know today of book ownership in the late Middle Ages and early modern period is principally based on contemporary inventories. In the libraries of famous personalities, prayer books are rarely mentioned, although the inventories of Duke Jean of Berry are an outstanding exception to this rule, listing numerous Books of Hours of different sizes including the tiny book made for Jeanne d’Evreux.2

The smaller the books, the more intense the transition between treasury and manuscript production becomes. This became clear in the

16

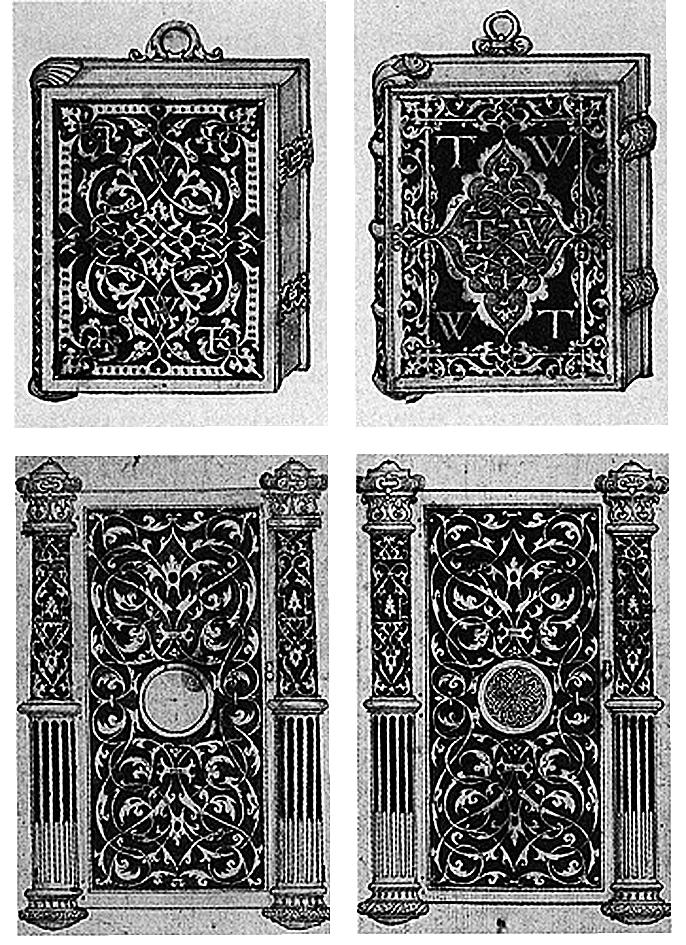

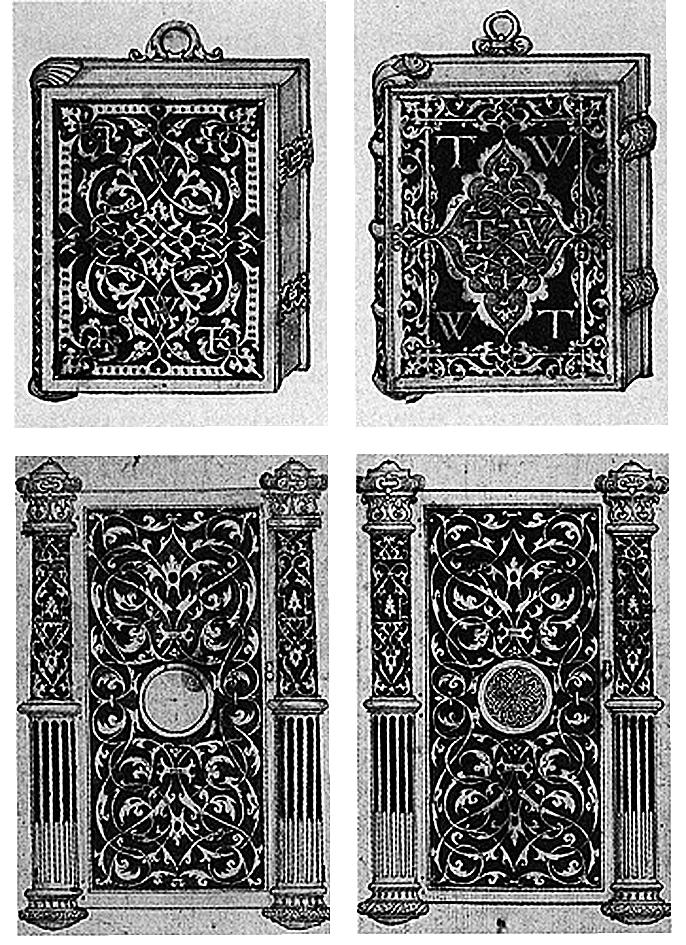

Hans Holbein: Design for a binding, London, BM

1991 Greenwich exhibition that depicted the European aspirations of the English court during the reign of Henry VIII. This modern mise-enscène did not show the few miniature books with the manuscripts except in one instance – the image of the King being the main reason – in the context of the flourishing tradition of miniature portraits. The others were assembled amongst the goldsmitheries. Hugh Tait, the connoisseur of applied arts who had already published the most important essay on these works of art, was entrusted with the description of these books.3

Girdle Books for Men

In old English sources these booklets are either called “tabletts” or “girdle books”, a term still used today. However, it is ambivalent in English, and its use is limited to the English-speaking world. It is one of the few technical terms that have not come into widespread use internationally.

The term “girdle book” leads to a certain confusion of the concrete function of such an object. Sometimes they are defined as books that can be knotted to a belt with a fine ribbon or a simple robe. Such a girdle book might look like the one Saint James Major carries with him on his pilgrimage in the painting by Hieronymus Bosch4 or as the scuffed codex in the hands of Canon Joris van der Paele whom Jan van Eyck portrayed in 1436 in his famous painting of the Virgin Mary today in Bruges. Those books are

always bound in solid cloth or some type of buckskin that overlaps the edges of the text block so that it can be bound together on its top edge and attached to the belt. Naturally, a rather small size is not suitable for such a purpose; a real girdle book always had to have some weight.

The goldsmith, of course, had nothing to do with the production of a girdle book used in this manner, unless he had the task of fabricating the belt that was to carry the book. Closures, ample chain links and even an entire belt could be made out of precious metal. Another type of book, covered in gold and silver and decorated with precious stones and enamels, is the type of girdle books favoured at the court of Henry VIII. A manuscript of this size might be reduced to just a few text passages, since it was not supposed to be attached to the belt but to fit into its pattern as a chain link so that these little books could be carried around like amulets.

The contents were all the more personalized since the little books could only include very short texts. Hence, every selection was a personal one. The smallest book of the Vatican Library, for example, only contains two short prayers to Saint Anne and Saint Francis of Assisi. They were apparently assembled because a hitherto unidentified couple, Anne and François, commissioned the little volume measuring just 39 by 29 millimetres.5 After the institution of

17

the Anglican Church under Henry VIII, several contents of the Roman rite were abolished and it might have been a demonstration of loyalty to the king that one of these books was decorated with a portrait of Henry VIII.6 It is the king’s portrait that endowed the Croke Girdle Book, today in the British Library, with apotropaic powers. It is one of the small books that was intended to be carried as an amulet. In spite of its small size, it is more likely to have belonged to a man than a woman. These extreme miniaturisations of girdle books allowed men to carry them into battle and always keep their prayers and images close at hand when they could not travel with complete prayer books.

A binding with embedded enamels from the period around 1540 also points towards a male possessor since the selected scenes from the Old Testament were not very suitable for a female owner. The original book however was replaced by texts printed in 1574.7 The strongly miniatur-

ised images on the covers – the Brazen Serpent depicted on the front cover and the Judgement of Salomon on the back cover – copy illustrations of the English Bible printed in either 1539 or 1540; the whole binding may reasonably be attributed to Hans of Antwerp.8

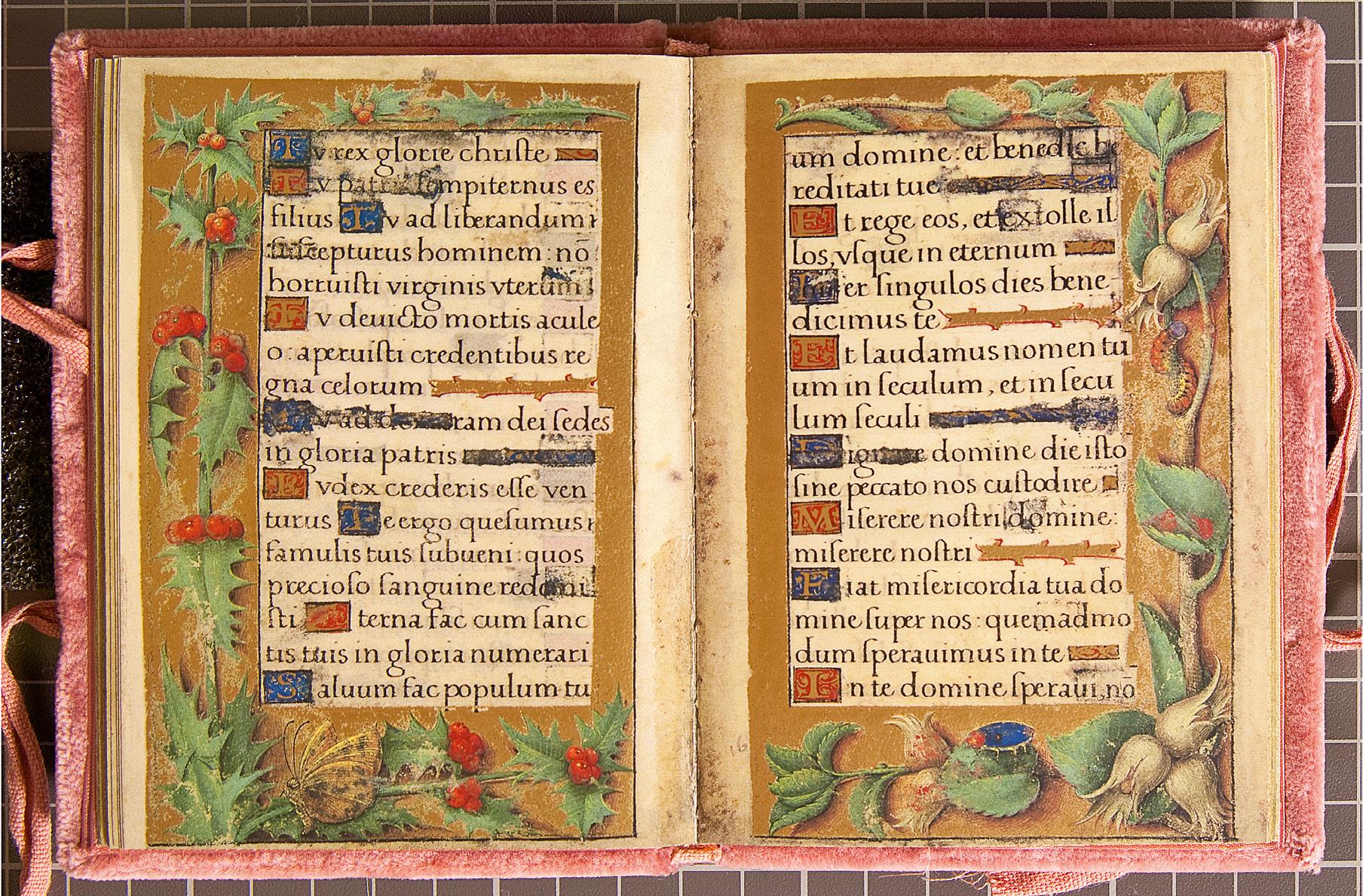

Another fully preserved Book of Hours in Chantilly is still bound in its original gilded filigree binding. It was formerly known as the Morosini Book of Hours and is today named after the delle Torre or Torriani family, without decisive proof that the book was really made for a member of this noble Milanese family.9 The binding’s gilded silver plates measure 82 by 61 millimetres and on each cover, four angel heads are placed around the small reliefs of Saint Catherine and Saint Lucy. Two enamel plates inside the book’s cover show the Kiss of Judas and the Carrying of the Cross. The miniatures themselves are closely connected to the ducal court in Milan and are attributed to the workshop of Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis.

18

London, BL, Stowe 956

London, BL, Stowe 956

The illumination is contemporary with the binding, thought to have made around 1490.

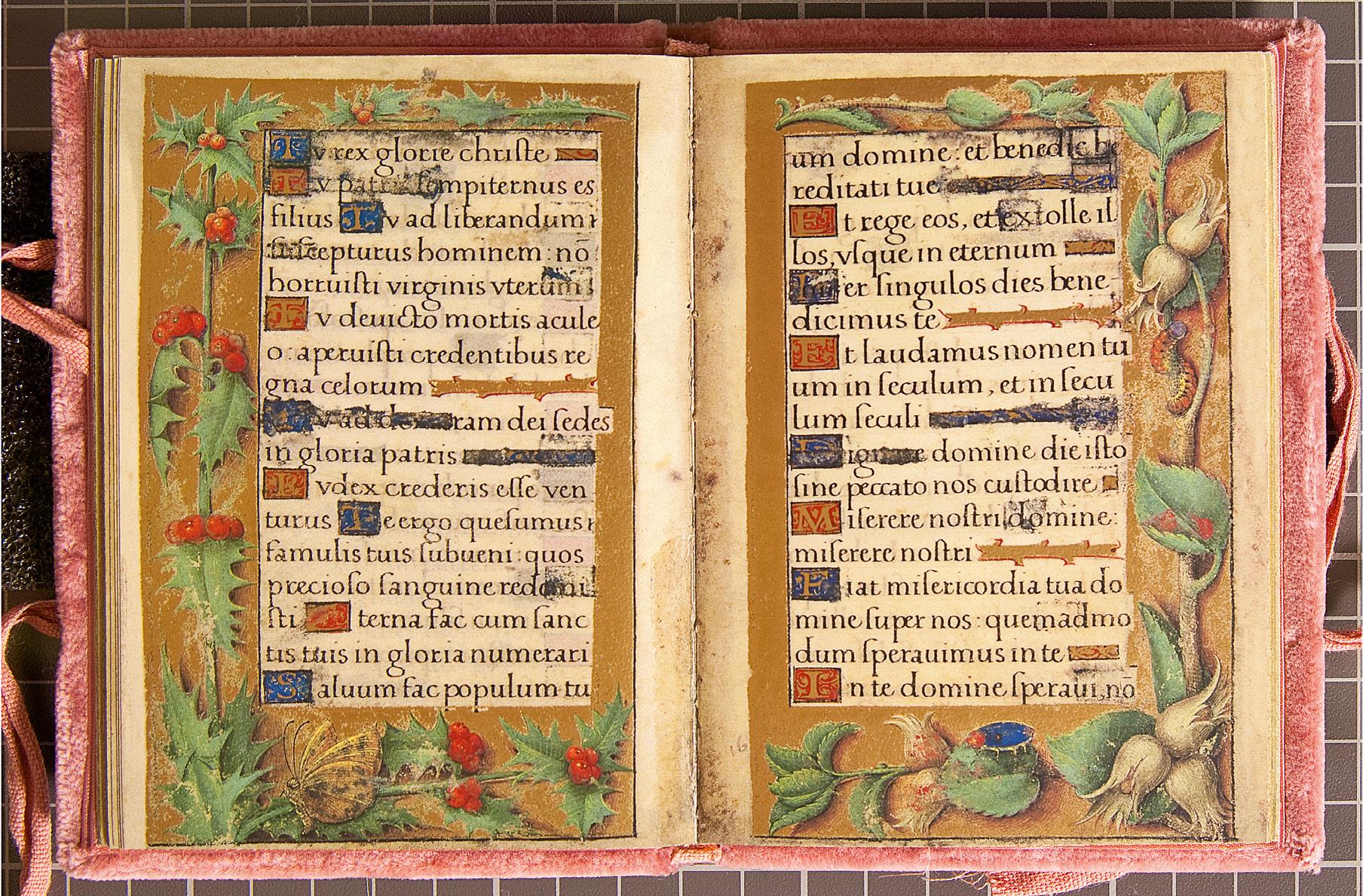

Another seemingly complete Book of Hours in a far smaller format, which resembles the layout of the English girdle books, was doubtlessly destined for Charles VIII of France, who is believed to have received it as a gift from the Duke of Milan, Ludovico il Moro.10 The remarkable Lombard painter Pietro Birago, who also started working on the miniatures of the Book of Hours of Bona Sforza in London that was later finished by Gerard Horenbout for Margaret of Austria,11 might have been its illuminator.

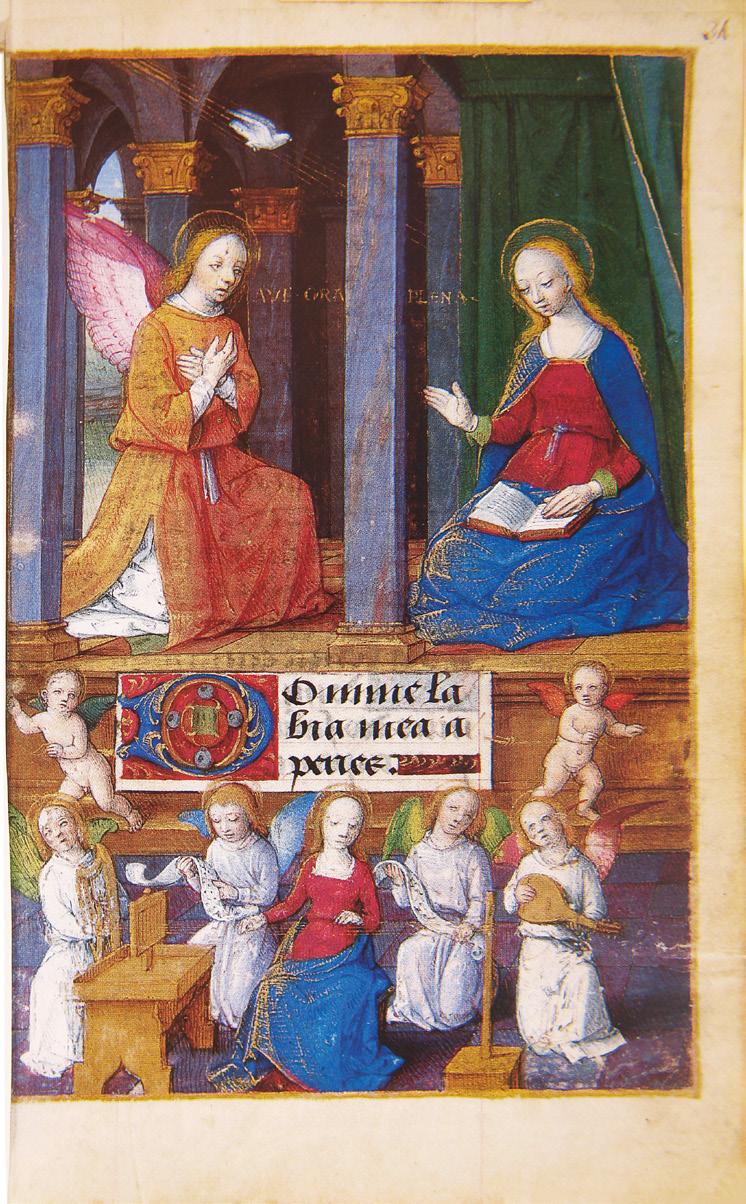

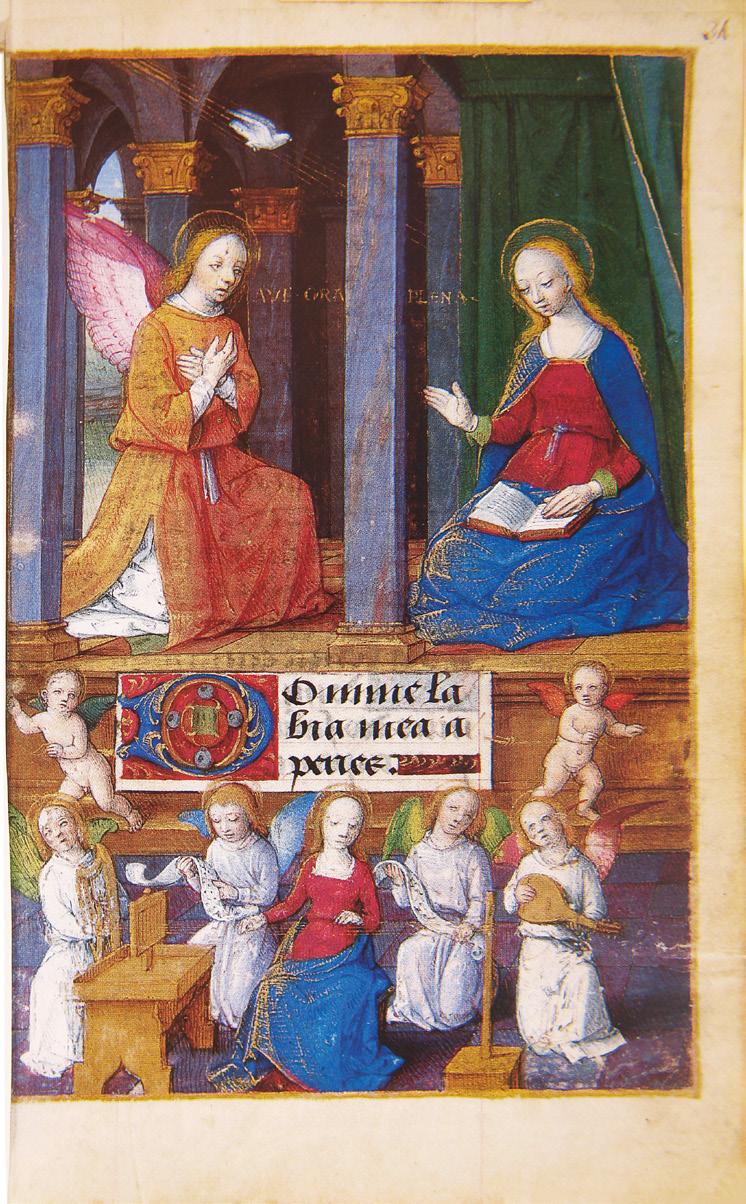

The commission was probably related to the war plans of Charles VIII, who, in 1494, pretended to go on a crusade in order to pursue his interests in the conflict for French supremacy in Italy. The full-page miniature on fol. 198v shows Christ himself handing over the fleur-de-lis together with the cross banner that shows not an abstract sign but a representation of the incarnated crucifix to the kneeling king. The accompanying prayer intercedes for heavenly support in the battle against the enemies (ad superandos hostes in bello) in Charles’ name whilst Charlemagne is glorified as the true predecessor. The book is of an exceeding richness of ideas; the Annunciation, for example, accompanied by choirs of angels, faces a depiction of Adam and Eve, who, as the sinful progenitors, pray for incarnation

and salvation in the miniature on the opposing page with the Incipit.

Unfortunately, the original binding was replaced in the seventeenth century12 but the key element in its association with the courtly milieu is not the fact that this book was without a doubt made for a man but the time it was made in. The Duke of Milan would have only commissioned such a splendid book for the French king with reference to Charles’ planned crusade if he himself feared the French intervention in his territories on the eve of the Italian adventure of the French.

The Credo made for Emperor Charles V might be seen in the same context. Measuring just 42 by 25 millimetres, it was planned as a little gem bound in gold enamels and set with garnets.13 The military context demonstrated by the miniature showing Charles VIII in front of Christ leaves no doubt that this little treasure was to be carried along in battle, quite probably on the belt or maybe even attached to one of the chain links.

Little Treasures for Women

When the inner beauty is visualized by the precious settings that these objects were furnished with, treasures of this kind were certainly made for women. However, it cannot be always decided with absolute certitude whether these treasures were made for a man or a woman.

The most esteemed court artists often created these bindings. Even Holbein designed such

19

goldsmith’s work of purely ornamental design and once adorned with the monogram T W I, as the related drawings, today conserved at the British Museum, prove. The book was probably made for Thomas Wyatt and his wife Jane Haute (married in 1537). The little ring in Holbein’s drawing shows that both the ribbon and the book, which is still preserved at the British Museum, were intended to be carried on the girdle.14

As stories tell, these precious objects were sometimes even connected with some legend; it is told that Anne Boleyn had given such a book to a lady from the house of Wyatt before she ascended the scaffold. Coincidentally, such a book was still in the possession of the Wyatt family in the nineteenth century. It was not the one designed by Holbein since it did not carry any initials.15 Such fate meets with the story that the little Book of Hours today in the possession of the duke of Württemberg in Abtshausen once passed the hands of the unfortunate Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots. This manuscript, one of the smallest examples known, is also missing its original binding. It was beautifully rebound in the early seventeenth century and nothing of its present appearance refers to the precious shell it once had.16

A Delightful Tradition until the Era of Emperor Rudolph II

Our binding is missing the little rings and loops it would have needed to tie the unknown

book it once covered, let’s say, to a belt perhaps. Hence, the inclusion of the girdle books of the time of Henry VIII can just be understood as a short excursion in our discussion for a better understanding of such small works. Still, the few examples that are still preserved today either as originals or as designs such as in Holbein’s drawings offer astonishing parallels to our example. Both convey the venerable tradition of binding religious books in gold and precious stones. It stems from the old habit of covering Gospel books, missals and other liturgical manuscripts with valuable materials in a manner that is adopted here from the previously preferred large format to the extreme miniaturisation of the prayer book.

Intermediate forms can be found in the superb 16o Books of Hours in Florence and Munich made around 1485 in Florence for the daughters of Lorenzo de’ Medici and bound in magnificent metal bindings. One of these also covers the famous Ghislieri Book of Hours made in Bologna.17 Goldsmiths’ bindings of the Middle Ages and Renaissance were already extremely rare at the time. We might also mention the Lombard Book of Hours from our catalogue, which was illuminated around the middle of the fifteenth century and later covered by a most likely Venetian binding at the turn of the century. The text block was unfortunately cut at the edges on

20

behalf of its new owner to fit into the precious cover.18 In the year 1532 an enamel binding was made for a Book of Hours of northern French origin, which had been acquired by Alfred Rothschild in 1862 and is now in a private collection.19 Only a few selected artists manufactured these treasures and, as we already mentioned, even Holbein was commissioned to furnish designs for such a purpose. Especially in England, artists such as Hans of Antwerp who previously worked in his hometown were ordered to the court to create their masterly designs. In Paris, the outstanding centre of goldsmithery throughout the Middle Ages that was troubled by civil war and political instability in the period around 1400, such tremendous works as the Goldenes Rössl of Altötting came into the world.20 By the sixteenth century, other centres emerged, among them Munich. Here, a virtuous art of goldsmithing had developed already in the mid-sixteenth century; its impact also characterises the refined work of our binding. Originally working at the court of the Wittelsbach, the craftsmen later moved to Prague to work there on behalf of Emperor Rudolph II around 1600.

A Unique Binding from Prague around 1600

The magnificent treatment of the Christian high feasts on both cover plates – Christmas and Easter – joined together with the instruments of the Passion of Christ on the spine is exceeded by

the masterly design and the priceless quality of execution. The spine of the cover imitates five raised bands and the repoussé work even tries to imitate, in subtle niello, the bookbinder’s stitches.

The mere weight of the golden covers requires hinges to connect them to the spine. Both joints are connected with a semi-circle that is horizontally aligned over the spine of the text block. The cover edges are framed with a niello border and the medallions emerge in a gentle curving from the flat surface of the cover panels. The translucent enamels, especially those of the larger blossoms, develop a surprisingly dynamic volume that animates the relief of the surface. This lively play of materials is perfected by the metal cornerpieces decorated with square-cut diamonds. Both cover frames are jewelled with 20 diamonds each. Four larger diamonds in each corner-piece that are arranged in a circular form around the centre medallions accompany them and slightly smaller square-cut diamonds are inserted in the four corner-pieces of the back cover. The same patterns of arrangement are followed by the diamonds in two different sizes that adorn the headbands and the two jewels on the clasp. No less than 56 sparkling diamonds attest to the exceptional complexity of this astonishing work of art. It should be added that comparable bindings mentioned still to be mentioned were all made of gilded silver whereas our example consists of pure gold.

21

Our binding does not carry one of the usual marks. It is, as specialists call it, unmarked –which means that must have been a courtly commission.21 On the other hand, the high status of the binding does not allow us to ascertain which workshop produced it. But if we compare its enchanting beauty to other contemporary works, it is easy to discern that it was certainly crafted by an unsurpassable master. It reminds us that, in 1570, the goldsmith David Altenstetter came from Cologne to Augsburg to establish his workshop in that famous Swabian city before he left for Prague in 1610 to spend the last seven years of his life as the imperial court jeweller. The family altar of the Bavarian duke Albrecht V that he made together with Abraham I Lotter around 1573/74 and that is today conserved in the treasury of the Munich Residence already shows certain stylistic prerequisites of the same subtle ornamentation that embellishes our binding.22

One of his contemporaries was Hans Karl who worked in Nuremberg and Augsburg. Both were masters of the enamel technique that attains new heights in our binding since it surpasses the anxious need for symmetry that the more traditional contemporary goldsmiths valued as a priority of their works.

A silver binding from Nuremberg made by Hans Lencker in 1574 is comparable to our work, although its size of 150 by 95 millimetres with a depth of 30 millimetres exceeds the dimensions of our small format.23 The covers are furnished with oval medallions that show the creation of Eve on the front and the Last Judgement on the back over. The centrepieces are framed by the four evangelists in the corners on the front and with depictions of the four virtues, Fides, Spes, Caritas and Prudentia. The spine is, as is our example, decorated with repoussé work. The hallmarks of the city of Nuremberg, Lencker’s

22

Twelve Meals of Christ, South Germany, 1619/20: binding

mark and the date 1574 are given beneath the raised bands. The prayer book contained within was made around 1600 or slightly later.

To depict the medallions representing Christmas Eve and Easter, the designer or responsible goldsmith surely found inspiration in contemporary works of arts, especially engravings. But his real contribution manifests itself in the impressive aesthetic effect that originates in the interaction between the function and its ornamentation. The central placement of the medallions ennobles them but truly triumphant is the sense of nature conveyed in the blossoms surrounding them and the keen understanding for abstract patterns on the fields of the spine. Although flowers and blossoms do not play an important role in the decoration of the embedded manuscript itself, one might nevertheless compare the abstract placing of the patterns to the border decorations with their numerous allusions to Christian belief as well as decisive references to the person for whom this little treasure was made at the beginning of the sixteenth century.

And Yet Another Happy Coincidence

Whoever wanders through images of the past should not be tempted to believe in absolute uniqueness. It might seem disappointing at first that none of the books displaying a general overview of goldsmiths’ work mentions a second binding comparable to ours, but then, what a

surprising coincidence! In 1993/94, I described a booklet in the catalogue Leuchtendes Mittelalter VI for the antiquarian book dealer Heribert Tenschert that corresponds astonishingly well to our binding, although the content of the book itself does not have much to do with the things that concern us here.24

It is an anonymous text called “Vonn Miniatur gemahltes Büchlein die 12 malzeitten Christi sampt der Schriefft” (Little booklet painted by hand containing the Twelve Meals of Christ and the Scripture). A protestant compiler selected corresponding texts from Luther’s translation of the New Testament that were copied by hand and accompanied by twelve coloured pen drawings preceded by a sumptuously decorated title page. Where this manuscript was made cannot be decided with certitude. I thought of the free imperial city of Augsburg back then, where the tolerant governance allowed local artists to accept works of both confessional contents.

Apart from its horizontal format measuring 41 by 51 millimetres, the design of the gold binding is closely related to the present item. The raised bands of the spine are covered with grooved repoussé work. The clasp is attached to the cover with comparable semi-circled enamel bosses that are shaped like slightly notched blossoms in this example. Whilst the text – as the title already includes – is conceived in conjunction with the

23

associated pen drawings, the binding is of a purely ornamental appearance. Magnificent flowers are laid around the centrepieces in a somewhat asymmetrical arrangement that creates an overall perfect effect. This time, the medallions are not shown with the crowned Jesus monogram IHS (however common with the Jesuits and acceptable for Protestant use) above three nails on the front and the pentagram of the Hebraic name of God on the back cover.

In 1993 I still missed the point that the final use of this binding could be the consequence of a rededication. Although the spine of the book and the clasp work perfectly well, the letters of the monogram should stand upright but instead are rotated ninety degrees. This particular arrange-

ment would not be surprising if one considers the possibility that the cover plates were originally made for a booklet of the more common vertical format. Not until then was the responsible goldsmith commissioned to adapt the cover plates to the horizontal format of the Twelve Meals of Christ. Thus, the panels were turned around ninety degrees and the hinges for the spine were fixed to the former bottom edge of the plates. Yet again we reach a point where such an exceptionally precious work of art did not retain its originally intended appearance.

But this is not the right place to speculate on possible reasons for the subsequent rearrangement. If the attribution to a workshop active in Prague is accepted, it would meet a conclu-

24

New York, PML, M.1166

sive historical point: after the death of Emperor

Rudolph II in 1612 and the quickly subsequent death of his successor Matthew in 1619, the state of Bohemia passed to the protestant Elector Palatine Frederick V in the winter of 1619/20 who encouraged iconoclastic riots in Prague during his short regiment. During this time, the already finished binding with the IHS monogram and the pentagram might have been passed onto a new possessor, this time a follower of the Protestant belief who used it to cover a manuscript based on the Lutheran version of the Bible.

This proposal remains a hypothesis that however allows us to also delineate the stylistic relationship of the two goldsmith bindings and to retrace their sequence of origin more concretely. Defining works such as the family altar of Duke Albrecht I made in Augsburg and dated 1573/74 as the stylistic premise, the gold binding of our Book of Hours could be a work from Prague during the time of Altenstetter’s activity at the court of Rudolph II dating from the time shortly after 1600. Other works from the emperor’s treasury would confirm this thesis.25 However, the closest stylistic affinity is found in a table clock made by David Altenstetter in Augsburg, today conserved in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.26

Slight compositional differences and the new freedom and opulence of the floral designs should place our binding in the period

of the last flowering of goldsmithery under the reign of Rudolph II. The second golden binding, the one later turned around ninety degrees to fit the Lutheran text of the Twelve Meals of Christ, must then have been reworked by the same goldsmith who initially prepared the cover plates for a booklet in a common vertical format because the spine and the clasp are worked in the same technique and style – in an rearrangement which must have taken place in the winter of 1619/20!

A Book Made for Claude of France

Whoever wants to learn about the prayer books of women of the high nobility at the dawn of the early modern age might assume that the exuberantly growing literature in historical gender studies offered some new and enlightening material on this subject. After the passing of Myra Orth and Janet Backhouse, more recent literature on this topic however tends to neglect the Books of Hours and prayer books made for noble ladies; they take so much pride in focussing on or astonish with a lack of knowledge on this topic, even if the title might pretend otherwise.27 In a research that is only focused on words, it is often the only aim to find passages explicitly written for the heroine of such a study. However, sacrificing the books used for daily prayer shows at the same time a disdain that contests the historical value of these manuscripts. Maybe modern authors might occasionally fear the consequences of their hero-

25

ines and spiritual sisters still having been raised to turn daily to their books of prayer.28

One often reads that prayer books were personalised in several ways, after the wishes of their patrons. Although the text had to be rewritten by hand every time and thus allowed numerous changes to include personalised passages, examples of Books of Hours that include personalised prayers or even modify certain passages in the common section in a way that would truly personalise them are very rare. The traditional prayer texts were apparently so fundamental and

dear to the patrons of these books that even slight modifications of the known forms are almost never found.

Remembrance of the Parents in the Office of the Dead and the Penitential Psalms

It is all the more surprising that the most important reference to the first owner of our manuscript can be found in an altered text. The third-tolast prayer in the Book of Hours starting on fol. 119 is, as John Kebabian already noticed in his description for the antiquarian book dealer H. P. Kraus in 1974,29 extended with a personal dedi-

26

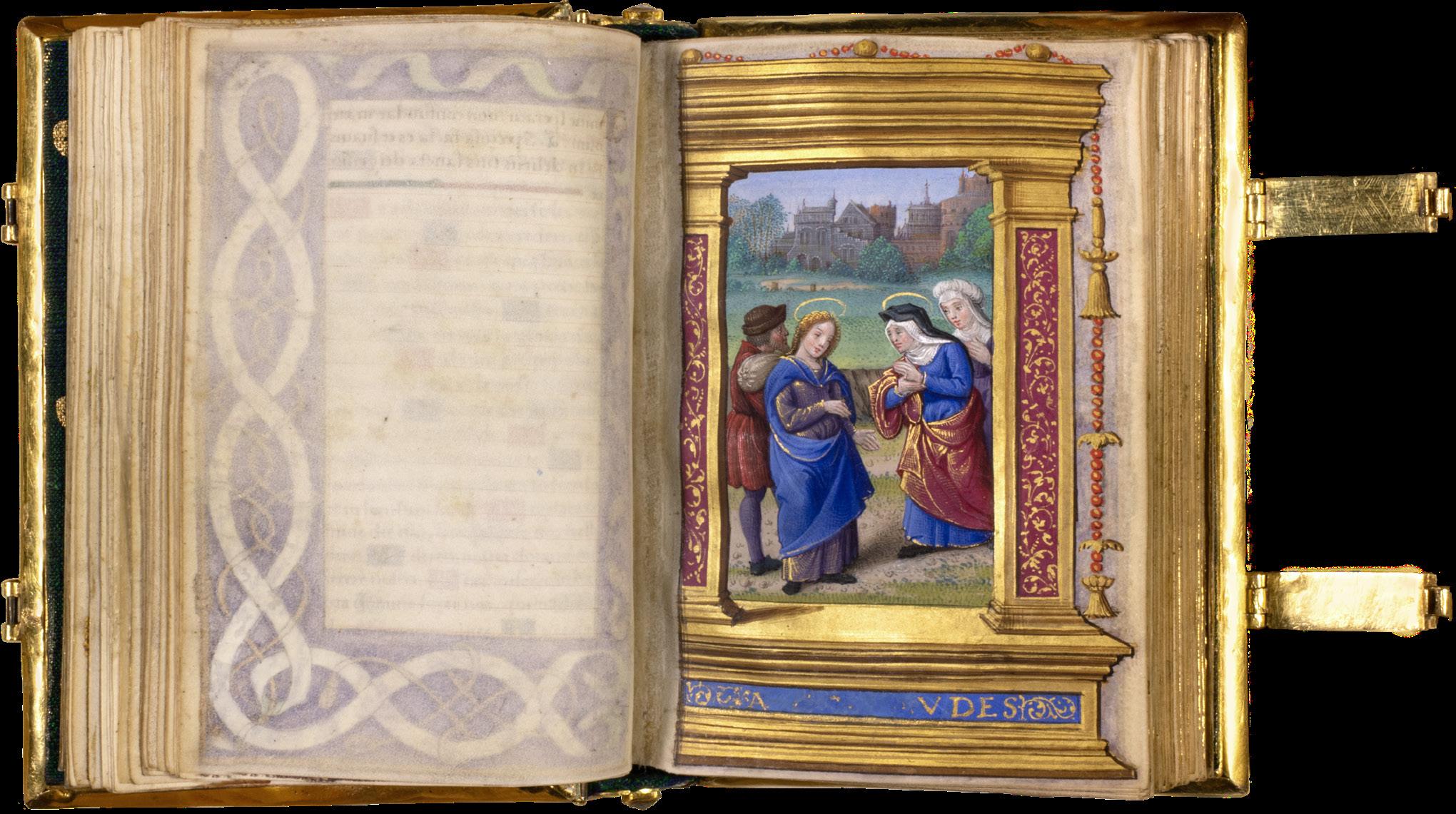

fol. 43v-44: birth of Christ with coat of arms erased

fol. 94v-95: prayer for the parents

cation: “Inclina domine aurem tua(m) ad preces nostras quibus misericordiam tuam supplices

deprecamur, vt animam famuli tui Ludovici

Regis patris mei: et animam famulæ tuæ Annæ

Reginæ matris meæ: et animas omnium fidelium

defunctorum, quas de hoc seculo migrare iussisti: in pacis ac lucis regione constituas et sanctorum tuorum iubeas esse consortes.”30

This concrete personalisation is found in one of the final prayers of the Office of the Dead that usually just mentions more generally the souls of all pious deceased. In several instances it is used twice to commemorate a single soul in

the beginning that merits a particularly intense remembrance without calling the deceased by name and in a second reiteration then remembers the souls of all deceased.31 In the royal Books of Hours made in Tours this prayer rivals with another tradition represented by the chief works of Jean Bourdichon, such as the Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany and the Books of Hours for Charles VIII and Frederick III of Aragon.32 In a row of three prayers at the end of the Office of the Dead, the second one is most commonly “Deus venie largitor et humane salutis amator quesumus clementiam tuam ut nostre congrega-

27

tionis fratres sorores propinquos et benefactores nostros: qui ex hoc seculo transierunt beata maria semper virgine intercedente cum omnibus sanctis tuis ad perpetue beatitudinis consortium pervenire concedas.”33

What earlier literature on this manuscript did not notice is the fact that this personalised prayer is not just cited at the end of the Office of the Dead. The final prayers at the end of Vespers and Lauds of the Office of the Dead repeat the

same wording; therefore it appears already on fol. 95. The personalised text has been used again a third time in a setting that is more unusual for commemorative prayers: The text block of the Penitential Psalms and the Litany ends with the same prayer on fol. 89, followed by the prayer Deus venite largitor and the Fidelium omnium conditor.

Since all three transcripts of the prayer Inclina aurem tuam on fols. 89, 95 and 119 explicitly mention the father and the mother by name, there is no doubt that our Book of Hours was written solely for one of the surviving children of King Louis XII of France and Queen Anne of Brittany. Only the two daughters that survived the royal couple come into question as the owners of our manuscript: Claude (1499-1524)34 and Renée (1510-1575).35 A noble gilded and crowned C proves that only the older Claude can have been the original owner of the manuscript; it appears in the text border on fol. 17 and does not mark one of the important beginnings of the text. It is also traced on the verso of this page as a result of simplifying the working process, which was a common practise in manuscript illumination. The placement of such a C on this text page of minor importance might be explained by the text itself: a two-line initial C appears for the first time on fol. 17 and it might have been the association with the initial of the name of the princess that motivated the heraldic C in the border.

28

Modena, Bibl. Estense a .U.2.28 = Lat. 614

One searches on vain for comparable deliberately placed letter Rs that would have pointed to Claude’s sister.

Only one further manuscript we know of today repeats the exact wording of the personalised prayer for Louis XII and Anne of Brittany. It is a manuscript that certainly belonged to Renée of France and repeats the prayer on fol. 16-16v.

This pious Primer was apparently composed for the little princess when she was a child.36 It seems very likely that she took it to Ferrara on the occasion of her marriage to Ercole II d’Este, which is why the book is today conserved at the fol. 16v-17: crowned letter C and coat of arms erased in the border

Estense library in Modena.37 In this manuscript, the prayer Inclina aurem tuam is even more rigorously separated from its original context than it is by being inserted at the end of the Litany in our Book of Hours. Without the two accompanying prayers at the end of the Office of the Dead, it is placed in the primer of Renée of France at the end of the gospel reading of Saint John, which has been treated as if it were a suffrage with a versicle, a responsory and the prayer Protector in te sperantium added. This reutilisation of a prayer for the commemoration of the parental souls in a book without an Office of the Dead does not

29

necessarily prove the primacy of our Book of Hours over the manuscript in Modena, and the relation between the two remains unsolved.

The Office of the Dead was prayed for the commemoration of the Dead and the intercession on their behalf. It is thus not surprising to find the names of parents who among the deceased were the first to be commemorated. In some Offices of the Dead, among a variable succession of prayers, one sometimes finds an intercession prayer for the forgiveness of parental sins: “Deus qui nos patrem et matrem honorare precipisti miserere clementer animabus patris et matris mee eorumq(ue) p(e)c(ca)ta dimitte. meq(ue) cum illis in eterne claritatis gaudio fac videre”38 as it is written in Berry’s Très Riches Heures on fol. 107.39

Closer to the period that concerns us here is the Guémadeuc Book of Hours that I published in a facsimile edition in 2000 with an accompanying commentary volume. The wording of the prayer includes a formulation that demands a concrete name. We read on fol. 94v: “animam famuli tui. N. et animas omnium fidelium defunctorum …”, followed by the prayer Deus qui nos patrem et matrem that was just mentioned but not copied in the Book of Hours for Claude of France.

The proximity of the prayers in both manuscripts cannot be explained by mere proximity of creation since the Guémadeuc Book of Hours was quite probably planned for Anne of Brittany herself

before it was given to a lady of the queen’s Breton entourage.40 Personalised prayers that might even include names are, as we already mentioned, very rare and it is all the more astonishing that it was common at the court of the Breton dukes to insert even entire texts that commemorated the outstanding position of the duke or the duchess in their Books of Hours: Pierre II, for example, prays in his hours for God’s intervention in the governance of his duchy,41 whereas Francis II and Marguerite of Foix pray for the conception of a heir in her London Book of Hours, just before the duchess finally conceived Anne of Brittany, who was later to become the queen of France.42

Elements of Personalisation of Book of Hours at the Court of Anne of Brittany

Personalisation of Books of Hours at the court of Anne of Brittany could be achieved by very different means. The only known examples, however, that include a modification of the standardised texts are those made for Claude and Renée. The inclusion of the names of their deceased parents makes our Book of Hours as well as the primer in Modena rare exceptions in the history of French prayer books. Portraits of the noblemen and women for whom these books were made are rarely found, one exception being Anne of Brittany’s portrait in the opening diptych of her Grandes Heures painted by Jean Bourdichon between 1503 and 1507.43

30

The two miniatures in the primer of Claude of France made in the early sixteenth century are like an amusing game of deception between Anne and her daughter Claude.44 Two full-page paintings showing the alliance coat of arms of Anne, consisting of Brittany and France, frame the text. The supplicant with the A of the queen’s name on the cloth of her prie-dieu kneels in the opening miniature, whilst the differently dressed daughter accompanied by the initial C is shown in the last miniature. Saint Anne accompanies the queen; Saint Claude assists her daughter. Although both appear to be of the same age, there can be now doubt that the artist meant to designate the mother and her daughter.

The mother and her child had been painted in another primer about ten years earlier; its borders vary with a sublime diversity the queen’s name, written in just three letters, ANE. Anne of Brittany commissioned Jean Poyer to illuminate this booklet for her son Charles-Orland (1492-1495), who died at a very young age. On fol. 10v, the queen is shown in confession, whilst the dauphin himself is kneeling in a dimmed room in front of an empty throne in the last miniature of the little book. He is depicted as a twelve-year-old, an age that he never reached, praying a highly unusual suffrage that intercedes for the seat of wisdom. He is thinking about his mother and himself when the text says: “… servus tuus sum. et filius ancille tue.”45

Anne of Brittany on the other hand did not commission the prayer book in Modena. That it was indeed intended for a girl is proven by the five miniatures showing a young female supplicant. Claude as well as Renée could be considered as its patrons because there is no concrete evidence pointing clearly to either one of the sisters. The history of the manuscript itself tells us the answer: It was Renée of France, married to a member of the Este family, who brought her own book, not one of her sister’s books, to Italy.

The miniatures of fol. 4, 4v, 5v and 10 show a girl or young lady in a rather unusual condition for prayer: as in the primer of Charles-Orland, she seems to be shown at an ideal age of youth that is comprehensible even if it does not betray a character of concrete likeness. The depiction of a prayer in front of the altar can be understood as a genre-like scene, as well as the confession in front of a bishop and the two mystical conversations with Christ. Along with these encounters, the young lady appears to visit the Lord in a church, so that he might teach her the right ways (fol. 5v). Another time, Christ appears to her in a radiant gloriole in her oratory. Already Margaret of York was represented like this in an impressive miniature in the London Add. Ms. 7970 that contains the Dialogue de la duchesse de Bourgogne à Jésus Christ, written by Nicolas Finet around 1470.46 The garments of the four figures in the Modena manuscript speak of high nobility; heraldic

31

devices are missing. In one of the miniatures on fol. 5v the physiognomy seems more individualised and the childlike features with the adorably chubby cheeks are found in yet another miniature: they characterise the physiognomy in the half-length portrait of the supplicant on fol. 2 in a somewhat larger format. It is quite probable that the artist really tried to portray the little princess here the way she looked when the book was made for her. It is clear that we stand at the dawn of the children portraits of the Renaissance that were

later to become a fashionable art in miniature format at the court of Henry VIII of England, painted by members of the Flemish Horenbout family and Holbein.

Since the portrait iconography of Claude of France does not offer reliable information and no other portrait of Princess Renée from her childhood is known, the quest for the identity of the little supplicant might lead to a new consideration: Instead of assuming carelessness of the illuminator on fol. 4, 4v and 10, we

32

Modena, Bibl. Estense a .U.2.28 = Lat. 614

Modena, Bibl. Estense a .U.2.28 = Lat. 614

could suppose that – in analogy to the New York Primer of Charles-Orland – the artist showed the patron and the child for whom the book was intended. If this was so, then Claude of France, who apparently commissioned the primer for her still underage sister Renée, would have had her likeness in prayer painted on fol. 4v, exactly as her mother did in 1495, whilst the princess who was to use the primer, was portrayed after life in a half-length portrait on fol. 2 and again in prayer for the guidance of Christ on fol. 5v.

Confronted with such vague assignments, it is not surprising that even the Books of Hours made for Anne of Brittany herself offer sparse evidence of their destination. This is true both for her Très Petites Heures in Paris47 and her Petites Heures,48 as well as for a little Book of Hours from the castle at Nantes, which is today inventoried as the Heures d’Anne de Bretagne at the municipal library.49

The Très Petites Heures, which for Nicole Reynaud

33

Cambridge, Fitzwilliam, 159

and her French colleagues are the key manuscript to define the artist’s personality whom I call in agreement with Ina Nettekoven the Master of the Rose Window of the Sainte Chapelle, shows just one alliance coat of arms of Anne of Brittany held by two angels in the lower margin on fol. 40v. The only heraldic device in this book is not painted on a page carrying a major Incipit but accompanies Lauds of the Office of the Virgin. Since a miniature of the Visitation precedes this passage showing two pregnant women, Charles Sterling constructed on this ground a conclusive historical explanation:50 Anne of Brittany paid just one extended visit to Paris, from May until August 1498, after the sudden death of Charles VIII. It was during these months that she might have commissioned the very small Book of Hours. It was not her only Book of Hours made in a Parisian workshop, but probably the first she commissioned there. It was then only after her second marriage to Louis XII that the alliance coat of arms would have been inserted on the Visitation page to emphasise the royal couple’s urgent need of an heir. The birth of a male successor did not follow, but the couple was blessed with the birth of Princess Claude of France in 1499. This Book of Hours is without a doubt one of the earliest testimonies of the cult of Saint Claude at the royal court; it might even be the earliest. The newborn princess received the very uncommon female name of Claude to

honour the saint, most likely out of gratitude, after Anne had went on a pilgrimage to SaintClaude in the Jura Mountains shortly after her wedding.

In the Petites Heures painted by the Petrarch Master, whom I believe to be Jean Pichore of Paris,51 a portrait of King Louis XII is sometimes considered in the depiction of Saint Louis who prepares a meal.52 Some borders are decorated with the name ANNE, occasionally reduced to its last letters NE, together with the heraldic ermine of the Breton ducal house. The cult of Saint Anne flourished during these years53 and the saint is venerated in the calendar, the Litany and the suffrages. Although the quality of the illuminations is worthy of a royal manuscript, Avril believed in 1993 that the traditional identification of the owner with the queen is not at all mandatory.54

In the case of the small Book of Hours from the Castle of Nantes (measuring 120 by 80 millimetres), the provenance of the manuscript that carries the reoccurring Initial A with a Franciscan cord reinforces the assumption that is was indeed made for the queen, because Anne’s most important device was the Franciscan cord. The Parisian origin of the manuscript, which is one of the better works of the so-called Master François but almost never mentioned in the literature, proves at the same time that several Books

34

of Hours, including the Très Petites Heures, were made in Paris for Anne of Brittany.

On the other hand, the curious case of the Laing manuscript in the University Library of Edinburgh cannot be fully explored here: fol. 1 is emblazoned with the alliance coat of arms of Anne of Brittany.55 But this Book of Hours is made for the use of Toul, something that is not really suitable for a queen from Brittany who only resided in the Touraine and in Lyons. There is no ample evidence in favour of a royal destination of the prayer books made for Anne of Brittany and her children. This lead me to assume in 2001, that the Guémadeuc Book of Hours,56 with its emphasis of Saint Anne and Saint Claude, was probably commissioned by Anne of Brittany in Lyons, although she probably never used it but quickly passed in on to a Breton lady of her entourage.

The complex history leading to the identification of the court painter Jean Bourdichon on the basis of Anne’s Grandes Heures with her portrait, coat of arms and monogram does not need to be retold here. Only the rather small primer made for Charles-Orland (Morgan 50) and the large primer of Claude of France (Fitzwilliam 159) are marked by comparable signs of destination: they also bear portraits, names and other heraldic devices.

Miniature Formats for Kings and Queens

One further distinct characteristic of our Book of Hours that shows the destination for the children of Anne of Brittany in its textual modifications can be interpreted as an indirect clue to its original ownership: the miniature format. Of course, Jean Bourdichon illuminated the magnificent book justly called the Grandes Heures for Anne of Brittany, but usually the small format was preferred. The same preference also leads to the little book today in the possession of the ducal family of Württemberg, the devotional tradition of which can be traced back to Mary Stuart, Queen of the Scots.57

This tradition of Books of Hours in a rather small format at the French royal court dates back, as we already indicated, at least to the time of Charles VIII. A further manuscript measures 70 by 50 millimetres and is adorned with the royal coat of arms, the device plus qu’autre and the name of Anne of Brittany’s first husband charles viii in Gothic book script.58 The borders are filled with fleur-de-lis and the crowned K of Charles’ name in a decorative pattern that was already used in the rose window of Sainte Chapelle in Paris. The book also contains a prayer to Saint Claude, although it was added to the original manuscript a bit later. The little book might be connected with a notice by Philippe de Commines, who mentions that the king called for the sacred assistance of the saint from the Jura region: “Que

35

Monseigneur saint Claude me soit en ayde.” The manuscript, today in a private collection, was made not at the Loire but in Paris, in the milieu of early printing that Charles VIII promoted more than any other regent. The miniatures were most likely painted by the Paris Master of the Chronique scandaleuse. His style allows a rather late dating of the book just before the king’s death in 1498.

The Miniaturisation of Script

The Hours of Charles VIII just mentioned measure 49 by 31 millimetres.59 Our manuscript is organised with the same width but with

a height of 60 millimetres; it is more elongated than the Italian codex. This is not the place to relate the history of the miniaturisation of Books of Hours that had already begun in the fourteenth century.60 A rather rectangular script that we call Gotico-Antiqua or Fere-Humanistica, which is easy to read with healthy eyes, was chosen for the king who died in 1498. This type was already used in printing in the 1460s whilst a proper Antiqua or Roman type was first used in later books.61 This epochal difference cannot be emphasised enough: it meant an incisive adjustment for the scribe who did not change between

36

fol. 17v-18: crowned letter C and coat of arms erased in the border

thin and thick lines anymore but had to hold the quill in a steady angle to achieve a unified appearance of lines of constant fineness.

The manuscript for Charles VIII, from Paris, is written in 14 lines, whilst the Book of Hours made for Claude of France, which included the commemoration of her father, Louis XII, who died in 1515, follows a new aesthetic conception of the page layout, which tends to place far more lines of written text on one page. It is thus ruled for twenty-two lines per page, and its text is written in a far smaller Antiqua, or Roman script. The minute size of our book is nevertheless surpassed by a second manuscript once owned by Claude of France: Morgan 1166 exclusively comprises texts that belong to the standard equipment of Books of Hours but the substantial offices and hours are lacking. It is thus merely fifty-four leaves thick. The edges of the book block were trimmed more rigorously than our codex; it now measures just 69 by 49 millimetres with a justification of 46 by 27 millimetres.62

With twenty-one lines and a justification width just slightly (1 millimetre) smaller than the one of our manuscript, the New York prayer book fits extremely well into the picture: The line spacing in the prayer book is much more narrow, which is why the entire justification is about 10 millimetres shorter than in our manuscript. Apart

form these two examples, only the so-called Book of Hours of Mary Stuart, probably also made for a member of the French royal family amply falls below these miniaturised dimensions: With a width of 21 millimetres and twenty-one lines of written text, it is almost the same height (48 millimetres) as the prayer book of Claude of France in New York.63

Parental and Novercal Heraldry in the Margins Destined for Claude of France

So far, the exceedingly rich border decorations that adorn our Book of Hours of Claude of France has only briefly been mentioned. Regrettably, the two coats of arms on fol. 17 and 17v and on fol. 44 were erased at an unknown date. However, the basic colours of blue and silver match Claude’s known heraldry perfectly: although as a woman she did not bring the claim to the throne into her marriage with Francis of Angoulême, she was nonetheless the heiress of the royal couple and, as the daughter of Anne of Brittany, the heiress of Brittany. For this reason we can assume that the erased arms did not represent conjugal coats of arms but originally showed France on one page and Brittany on the other. The already mentioned crowned initial C in the border would have surmounted a French royal blazon with the golden lilies on an azure ground on fol. 17 and 17v, and the blazon in the border framing the Adoration of the Child initially would have

37

fol. 20v-21: armillary sphere in the border

presented the Breton ermine on silver.

Art history, a field that is fixated on images, has no choice but to prefer the little prayer book in the Pierpont Morgan Library. There, in the border decorations, the entire creative imagination of the artists finds its expression in various motives of the history of human salvation. Our Book of Hours follows a very different aesthetic and intellectual concept. Although it refers to a more traditional kind of border decoration it puts much more emphasis on abstract signs and most of all on the word itself; and therefore it repre-

sents an epochal step in the history of prayers in books.

In 1515, Louis XII died, just two years before conflicts over the old Christian dogmas grew more acute and found their first outburst when Luther nailed his ninety-five theses to a church door in Wittenberg and publically sparked the Reformation. France suffered from acrimonious fights in the aftermath and also the role of word and image for good Christians were discussed fervently. Claude’s Book of Hours follows the Old Catholic belief: the entire border decoration

38

is literally framed by the cord of Saint Francis of Assisi and thus by the Minorite discipline of faith. After the death of Charles VIII in 1498, Anne of Brittany founded a sisterhood of Franciscan tertiaries, women who lived a worldly life outside the monastic order. She herself was a member of this sisterhood, and Claude, too, had to join them.

Although the Franciscan ideas were clearly imbedded in the decoration of Claude’s Book of Hours, the rationality of the depiction of praying and the supplicant herself belong to a new era that already distrusted the image but still succeeded

in consolidating figuratively designed elements with the meaning of the written word. The motifs, which were used, are not just limited to traditional objects such as the recurrent chaplet, the so-called rosary, which have long belonged to the repertoire of the pious. They also make use of objects shaped by a culture of Humanism one would rather expect in the hands of a scientist than in the surrounding of a supplicant. It so happens that the Latin texts are not paired with vernacular language but with Greek and the Iberian motto non Mudera.

39

fol. 55v-56: pair of ailes in the border

All border decorations are painted on a ground coloured in violet. This colour should be associated with the amethyst, which in much earlier eras had been strictly reserved for the Byzantine emperor. They are framed by the Franciscan cord. Its threads are covered with golden and white (which signifies silver) objects. Apparently the walls of the oratories of Anne of Brittany and Claude of France were covered with such ropes in complex patterns, which one might confuse with sailor’s knots, of a more than practical meaning. Similarly decorated walls can still be found, for example, in the castle of Écouen and one of

Claude’s chambers in Blois is said to have had been covered with the same sign on yellow silk. On the calendar pages, these cords alternate with scrolls which carry the same message in three different formulations: they derive from the motto non Mudera already used by Anne of Brittany and are placed, according to their length, mostly in the inner and upper margins of the pages. It signifies the insistence on not changing oneself. This idea turns into the Latin motto of hope for eternal life, fir M itas eternitatis spe M duplicat. 64 This dictum is then translated into Greek, very often hard to decipher and written in

40

fol. 57v-58: ostrich feathers in the border

different ways, but we might deduct the following transcription: ′H ΒΕΒΑΙΩΤHΣ ΤΟΥ ΑΙΩΝΙΟΥ ΔΙΡΛΑΣΙΑΖΕΙ ΤHΝ ′ΕΛΡΙΔΑ.

The mottos in the borders call for firmness of belief that doubles the hope for eternal life. Claude’s mother had insisted on this as well as on the Franciscan cord, which signifies an intractably strong bound. Another element appears for the first time on the opening page of Matins of the Office of the Virgin on fol. 15 and underlines this context: This element is distinguished from all the other devices in the border decoration already by its strong colouring. It is the large blue initial S formed from bands of clouds. Placed between small painted stars, the queen’s old motto non Mudera written in gold letters can be read with some difficulty. The blue S reappears three times on fol. 45 and 45v accompanying Prime of the Office of the Virgin. Here it forms a sky strewn with stars and interlocked with three letters S composed of the Franciscan cord. In another instance, on fol. 24 and 24v, the ornament is composed of several interlocked letters. It can also be connected to the knotted cord, as on fol. 38v, the first text page of Matins of the Hours of the Holy Cross. The ornament is placed on the verso page of the Crucifixion and reappears in similar form on fol. 47 and 47v for the opening of Prime of the Office of the Virgin. The Old French term fermesse (firmness) can with a certain amount of fantasy be transformed into

a ferme S , a firm or closed S. The closed S appears four times on fol. 83 and 83v and again, more determinedly, on fol. 86 and 86v in the border decoration of the Litany with the major saints.

In both instances, it is made of a band of clouds gemmed with golden stars.

Since the beginning of the Office of the Virgin on fol. 15 marks one of the most important divisions of the Book of Hours, the blue letter S in the border is accompanied by yet another motive: an armillary sphere. It was already used as a personal emblem of Duke Francis II of Brittany and was inherited by his daughter Anne of Brittany. On different occasions, the armillary sphere appears throughout the pages of the entire manuscript, mostly on those pages that are already emphasised by carrying a major Incipit. The skilfully drawn instrument is often exquisitely shaded and masterly contrasted with the background. It is painted in varying sizes on different folios.

41

Ostrich feathers of Lorenzo de Medici

Particularly magnificent is its first appearance, especially because the knots of the cord are laid like beams radiating in four directions around the sphere rendered with a keen sense for illusion. The band originally intended for the zodiac sign carries the letters if M a M and in another instance the letters iiason; two inscriptions which had been “mysterious” to Charles Sterling.65 Their explanation is not all too difficult when one thinks of the course of the year. The two inscriptions quoted do not designate the sign of the zodiac but rather the initials of the months, from January to May and from June to November!

The armillary sphere itself signifies sagacity and melancholy; it surely was a conclusive sign for an intelligent but lonely woman as already Sterling had correctly observed.

The unknotted band that replaces the cords on several pages seems not to derive from Claude’s mother, Anne, but rather from her mother-inlaw, Louise of Savoy. Apparently Claude was on rather good terms with Louise, whose son Francis I was then made king of France. Roger Wieck obviously considers the rope to be a sign of Claude’s husband Francis, although already the erased coat of arms proves that the Book of Hours was made for the duchess and queen alone and does not refer anywhere else to her alliance with the king.

But Claude’s father, Louis XII, is honoured in

the border decorations of her manuscript: on fol. 56 and 56v, immediately following the depiction of the Magi currently identified as kings, three golden pairs of wings are painted in the border. Already in the time of the unfortunate dauphin Louis of Guyenne (died 1415), its French equivalent ailes was read as an L.66 The feathers that appear two folios later might refer to this association. Once brought into the game, probably because of the Adoration of the three Magi for Sext of the Office of the Virgin, this idea is repeated by two pairs of wings on the verso page of the Presentation in the Temple before it disappears from the repertoire of the border decoration.67 On the other hand, the paired wings should not be narrowed down to an exclusive reference to Claude’s father because they always appear paired. Moreover, the sign can have very different connotations that can be literally understood as winged.68

At least, the highly unusual basic colour of the entire border decoration takes on meaning when considering the pretentions of Louis XII. In 2001, his biographer Didier Le Fur described him as Un autre César and apparently, the French king dreamt about reaching for the imperial crown at the dawn of the early modern period. Charles VIII already carries it in a frontispiece of a manuscript today in the National Library in Paris69 and the fight for Italian supremacy, which

42

Another very rare motive, which appears in the border decorations, is closely connected to Italy: Like the paired wings, large ostrich feathers decorate several text pages. They are turned outwards and their form with the big curved peak resembles the characteristic appearance of the feathers associated with a famous member of the Florentine Medici family: Lorenzo il Magnifico, (14491492) used such sumptuous feathers – by that time called ostrich feathers – in a bundle of three, each of a different colour. In his heraldry they are held together by a diamond ring and embody the three virtues of faith, love and hope.70 The triad is not always mandatory; two feathers, for example, suffice in a Parisian Palatina manuscript.71 After the time of Lorenzo il Magnifico, the symbol even arrived at the Vatican during the papacies of the Medici popes, Leo X (born 1475, pope 1513-1521) and Clemens VII (born 1478, pope 1523-1534). The newly commissioned frescos of the Sala dei Chiaroscuri, for example, were decorated with the Medici feathers. They even came to Urbino with the arrival of Lorenzo II de’ Medici, who died in 1521 and was the father of the later French queen Catherine de’ Medici. It was Michelangelo, who designed and erected his monument in the Medici funeral chapel of San Lorenzo in Florence between 1524 and 1533.

By that time, it was believed that ostrich feathers were of an unprecedented homogeneity, and so they could also signify justice itself. Referring to this probable allusion, the paring as a comparison makes sense.72 The ostrich feathers in the Hours of Claude of France surely take the famous heraldry of the Medici into account, aware of the fact that the ruling pope came from this influential Florentine family. Their golden accordance achieved by their paring might well embody justice. Already Charles d’Angoulême, the father of Claude’s husband Francis I who already died in 1496, had ostrich feathers painted in his book of hours, latin 1173 in Paris, fol. 25 but as a matter of fact, they are not at all as uniform as their symbolism would require them to be.

The various references to Anne of Brittany, Louise of Savoy and Claude of France fit very well into the personalised conception of the book with its prayer on fols. 89, 95 and 119 – a supplication exclusively reserved for the daughters of Anne of Brittany and Louis XII – and the letter C on fol. 17 and 17v as part of a very unique and personalised language of devices. We should remember than an art historian dealing with such a richly decorated book cannot simply unreel a lexical knowledge of contemporary heraldry, but rather needs to complete the things we know about Claude of France with a profound analysis of the little book itself. Neverdefined French politics until the time of Francis I, has to be considered in this context.

43

theless there may exist a fourth little manuscript from the immediate circle of Claude and Renée: We know of the existence of a Book of Hours from the former Hachette collection, today in an Irish private collection, carrying the devise non Mudera together with the armillary spheres and paired wings as in our Book of Hours, this time on golden borders although not of the same high quality as our example.73

It should be emphasised that the ornaments are strictly limited to a woman and with the exception of the paired wings associated with Louis XII, all further motifs associated with a male possessor are omitted: there is no Orléans porcupine, the heraldic animal of Claude’s father Louis, nor the fire salamander of her husband Francis I.

Another look at the Modena prayer book highlights the historic importance of the Book of Hours of Claude of France. A comparable heraldry was not developed for Claude’s little sister, who first had to learn how to read. Since the girl was not yet a member of the Franciscan sisterhood founded by her mother, some attributes that we find in the Book of Hours made for Claude were not used in the Modena prayer book of her younger sister.74 In consequence, the Franciscan cord is missing, one of the most noticeable motifs used throughout the entire historiated border decoration in Claude’s Book of Hours.

Not even the commemoration of her father

Louis with an L or the paired wings, nor the motto non Mudera of Anne of Brittany, which still invokes Brittany’s heritage today,75 is found in Renée’s little book. Instead, it is strewn with lovely flowers such as the ones Jean Bourdichon painted for her mother; in contrast to Flemish contemporary border decoration, they are not just scattered over the margins but bloom on little branches that spring from the outer corners of the pages.

If we include the aesthetic appearance of the New York prayer book in our considerations, it seems to have been possible to choose between four different styles of border decoration. Architectural designs were reserved for head miniatures only to introduce the major Incipits. All of the manuscripts are decorated with full borders on every text page: The prayer book includes a narrative cycle, the Book of Hours includes numerous heraldic references on a light violet ground and the prayer book in Modena depicts blooming branches on a golden ground. The famous candelabrum borders, which, as we will come to learn, also belong to the repertoire of our painter, are not prominently represented in these three manuscripts.

The Miniaturised Format for Myopics?

Whoever had the chance to observe a nearsighted reader who tries to look at the Hours of Mary Stuart, especially at the opening of the

44

gospel of Saint John on fol. 13v that reaches the highest point of miniaturisation, might come to find an unexpected explanation for the trend of extremely small prayer books in this period: whereas a scribe surely could have copied such a manuscript only with optical aid, it is sufficient for the reader to just take off his or her glasses to be able to decipher the extremely small script.76

Apparently, several formats were tested for Anne of Brittany’s Books of Hours: some of them were designed as impressive quarto formats, such as the queen’s Grandes Heures, but also minuscule sizes. The Très Petites Heures was long thought to be the smallest manuscript known.77 Not all of the queen’s books were such experiments of miniaturisation,78 but, of course, there was a big difference between the layout for literary texts, non-fictional literature and the readings for the prayer: Some texts might have been read, but praying itself has been a very intimate and private matter ever since, even if modern researchers sometimes tend to claim that Books of Hours were still a part of the old tradition of collective liturgical prayer.79

The search for prayer books in a very small format sometimes brings surprises to light: we know, for example, from documentary evidence that, in 1497, Anne of Brittany paid Jean Poyer 153 livres for 23 miniatures and 271 border decorations in “une petites heures … à l’usaige