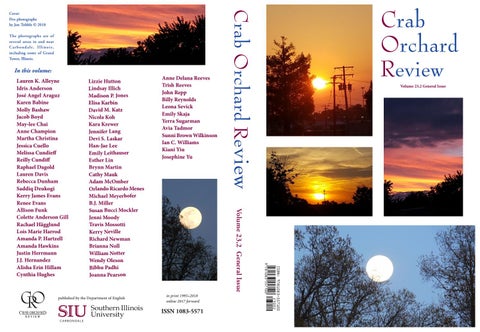

The photographs are of several areas in and near Carbondale, Illinois, including some of Grand Tower, Illinois.

In this volume:

CO R

CR AB ORCH AR D •

•

REVIEW

Lizzie Hutton Lindsay Illich Madison P. Jones Elisa Karbin David M. Katz Nicola Koh Kara Krewer Jennifer Lang Devi S. Laskar Han-Jae Lee Emily Leithauser Esther Lin Brynn Martin Cathy Mauk Adam McOmber Orlando Ricardo Menes Michael Meyerhofer B.J. Miller Susan Bucci Mockler Jenni Moody Travis Mossotti Kerry Neville Richard Newman Brianna Noll William Notter Wendy Oleson Bibhu Padhi Joanna Pearson

published by the Department of English

Anne Delana Reeves Trish Reeves John Repp Billy Reynolds Leona Sevick Emily Skaja Yerra Sugarman Avia Tadmor Sunni Brown Wilkinson Ian C. Williams Kiani Yiu Josephine Yu

Volume 23,2 General Issue

Lauren K. Alleyne Idris Anderson José Angel Araguz Karen Babine Molly Bashaw Jacob Boyd May-lee Chai Anne Champion Martha Christina Jessica Cuello Melissa Cundieff Reilly Cundiff Raphael Dagold Lauren Davis Rebecca Dunham Saddiq Dzukogi Kerry James Evans Renee Evans Allison Funk Colette Anderson Gill Rachael Hägglund Lois Marie Harrod Amanda P. Hartzell Amanda Hawkins Justin Herrmann J.J. Hernandez Alisha Erin Hillam Cynthia Hughes

Crab Orchard Review

Cover: Five photographs by Jon Tribble © 2018

in print 1995–2018 online 2017 forward

ISSN 1083-5571

Crab Orchard Review Volume 23,2 General Issue

A B ORCH AR R C D •

•

REVIEW

CR AB ORCH AR D •

•

REVIEW

A Journal of Creative Works

Vols. 23 No. 2

“Hidden everywhere, a myriad leather seed-cases lie in wait…” —“Crab Orchard Sanctuary: Late October” Thomas Kinsella Editor & Poetry Editor Allison Joseph

Founding Editor Richard Peterson

Prose Editor Carolyn Alessio

Managing Editor Jon Tribble

Editorial Interns Sarah Jilek Mandi Jourdan Nibedita Sen Sarah Schore

Assistant Editors Isiah Fish Ira Kelson Hatfield Dan Hoye Anna Knowles Ian Moeckel Meghann Plunkett Laura Sweeney Troy Varvel

Board of Advisors Ellen Gilchrist Charles Johnson Rodney Jones Thomas Kinsella Richard Russo

2018 ISSN 1083-5571

Web Developer Meghann Plunkett

The Department of English Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Address all correspondence to:

Crab Orchard Review

Department of English Faner Hall 2380 - Mail Code 4503 Southern Illinois University Carbondale 1000 Faner Drive Carbondale, Illinois 62901 Crab Orchard Review (ISSN 1083-5571) is published three times a year by the Department of English, Southern Illinois University Carbondale. We have transitioned from a print subscriptionbased publication to a online-only free publication. Single issues of our last two print editions, both double issues, are $20 (please include an additional $10 for international orders). Crab Orchard Review moved to an online-only publication in the Fall of 2017. Crab Orchard Review accepts no responsibility for unsolicited submissions and will not enter into correspondence about their loss or delay. Copyright © 2018 Crab Orchard Review Permission to reprint materials from this journal remains the decision of the authors. We request Crab Orchard Review be credited with initial publication. The publication of Crab Orchard Review is made possible with support from the Chancellor, the College of Liberal Arts, and the Department of English of Southern Illinois University Carbondale; and through generous private and corporate donations. Lines from Thomas Kinsella’s poem “Crab Orchard Sanctuary: Late October” are reprinted from Thomas Kinsella: Poems 1956-1973 (North Carolina: Wake Forest University Press, 1979) and appear by permission of the author. Crab Orchard Review is indexed in Humanities International Complete. Visit Crab Orchard Review’s website:

CrabOrchardReview.siu.edu

Crab Orchard Review and its staff wish to thank these supporters for their generous contributions, aid, expertise, and encouragement: Amy J. Etcheson, Angela Moore-Swafford, Linda Buhman, Kristine Priddy, Wayne Larsen, and Chelsey Harris of Southern Illinois University Press Bev Bates, Heidi Estel, Patty Norris, and Joyce Schemonia Tirion Humphrey, Matthew Gordon, and Jay Livingston Dr. David Anthony, Pinckney Benedict, Judy Jordan, and the rest of the faculty in the SIUC Department of English Division of Continuing Education SIU Alumni Association The Graduate School The College of Liberal Arts The OfďŹ ce of the Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Provost The Southern Illinois Writers Guild

Crab Orchard Review wishes to express its special thanks to our generous Charter Members/Benefactors, Patrons, Donors, and Supporting Subscribers listed on the following page whose contributions make the publication of this journal possible. Address all contributions to:

Crab Orchard Review Department of English Faner Hall 2380 - Mail Code 4503 Southern Illinois University Carbondale 1000 Faner Drive Carbondale, Illinois 62901

CHARTER MEMBERS*/BENEFACTORS Dan Albergotti Carolyn Alessio & Jeremy Manier Anonymous Pinckney & Laura Benedict Edward Brunner & Jane Cogie* Linda L. Casebeer Noel Crook Dwayne Dickerson* Jack Dyer* Joan Ferrell* John Guyon*

John M. Howell* Rodney Jones Richard Jurek Joseph A. Like Greg & Peggy Legan* Beth L. Mohlenbrock* Jane I. Montgomery* Ruth E. Oleson* Richard “Pete” Peterson Peggy Shumaker

PATRONS Robert E. Hayes Chris Kelsey Jesse Lee Kercheval Lisa J. McClure Anita Peterson

Eugenie & Roger Robinson Nat Sobel Betty Tribble David & Laura Tribble Clarisse Zimra

DONORS Lorna Blake Chris Bullard Heidi Czerwiec Charles Fanning Jewell A. Friend John & Nancy Jackson Reamy Jansen Rob & Melissa Jensen Jon Luther

Charlotte and Gabriel Manier Lee Newton William Notter Lisa Ortiz Ricardo Pau-Llosa Angela Rubin Hans H. Rudnick William E. Simeone

SUPPORTING SUBSCRIBERS Joan Alessio Joanna Christopher K.K. Collins Corrine Frisch John & Robin Haller Zdena Heller Karen Hunsaker Lee Lever

Charlotte McLeod Peggy & Albert Melone Nadia Reimer Lee Robinson Catherine Rudnick Peter Rutkoff Victoria Weisfeld

CR AB ORCH AR D •

•

REVIEW

General issue

Volume 23, Number 2

Fiction May-lee Chai Renee Evans

Fish Boy

1

Absentia

30

Amanda P. Hartzell

Out of Sofya

38

Justin Herrmann

The Rat, the Panther, and the Peacock

44

Devi S. Laskar

Stalks (Excerpt of Novel, Shadow Gardens)

57

Adam McOmber

Plumed and Armored, We Came

66

Orlando Ricardo Menes

La Luz School

70

Jenni Moody

Wingspan

93

Wendy Oleson

In Extremity

97

Joanna Pearson

The Field Glasses

119

Nonfiction Prose Karen Babine

Bones

138

Molly Bashaw

Arctic Ground Squirrels

142

Nicola Koh

Forgive Not My Transgressions

165

Jennifer Lang

The Fabric of Peace

171

Cathy Mauk

Present Progressive

202

B.J. Miller Kerry Neville

Skin and Walls

212

Teaching the N-Word in Georgia

214

Poetry Lauren K. Alleyne

Ugly Elegy or When Daughters Drown Their Fathers She who wears horns and weeps

13

Idris Anderson

Sugar House

19

15 17

JosĂŠ Angel Araguz Selena: a study of recurrence/worry St. Peter to Joseph Sentence Jacob Boyd One Looks at Two

21 23 24

Anne Champion

I Want to Marry a Communist

26

Martha Christina

Closed

28

Jessica Cuello

If

46

Melissa Cundieff

Ellipsis

47

Reilly Cundiff Raphael Dagold Lauren Davis

58 bald eagles

49

Night and a Morning and a Day

51

Pilgrimage to Saint Sara

52

Rebecca Dunham

The Fall of Manna

53

Saddiq Dzukogi Kerry James Evans

Unseen 55 Whataburger Is an Allegory for Everything

25

77

Allison Funk

The House Woman’s Double

79

Colette Anderson Gill

Ghazal for Akhmatova & Petersburg, 2008

81

Rachael Hägglund Lois Marie Harrod

Mother Tongue

83

The Hinged Heart

85

Amanda Hawkins

Plainspeak Driving Home the Ashes

87 89

J.J. Hernandez

The Tangerine Packing House Death Drive Looking

108 110 112

Alisha Erin Hillam

The Circus

113

Cynthia Hughes

Riding the Canadian Central

114

Lizzie Hutton

Marriage: The Factory Vacation: Berlin

115 117

Lindsay Illich

Aubade

118

Madison P. Jones

Pastoral

130

Elisa Karbin

Summer Squall

131

David M. Katz Kara Krewer

Money

132

Last Name

133

Han-Jae Lee Emily Leithauser Esther Lin

Wasted Tire

135

The Cliffs of Moher

136

Cholera Is What My Grandfather Did During the War

152

Brynn Martin

My Mother’s Nipples

155

Orlando Ricardo Menes

Macho

157

Michael Meyerhofer

Urban Legend

159

Susan Bucci Mockler

When Omair Shaaban Teaches Us How to Survive

161

Travis Mossotti

Déjà Entendu

162

Richard Newman Brianna Noll William Notter

Donut Tree

163

The Night the Coffins Open to Reveal Themselves Empty

182

Post Office in the Old Confederate Capital

183

Bibhu Padhi Anne Delana Reeves Trish Reeves

Storm in Summer Time Is Here Still.

184 186

A Garden in Winter Deer Season

187 189

And Someone Said ‘Forever’

192

John Repp

The Salt Hay

199

Billy Reynolds Leona Sevick

Sitting in the Car with Huck

200

Doll’s House, Provincetown Museum

201

Emily Skaja

The Brute / Brute Heart

223

Yerra Sugarman

The Teacher

225

Avia Tadmor

Ruth after Crossing the Water

229

Sunni Brown Wilkinson My Son Says He Has an Owl 231 Inside of Him— Girls of the Underworld 233 Butter on the Bread and Honey 235 on the Butter Ian C. Williams Boys Will Be Boys: A Confession 237

Kiani Yiu Josephine Yu

Pangaea

238

In Times Such as These, We Find We Must Make Do

239

Contributors’ Notes

241

A Note on Our Cover This cover features six photographs by Jon Tribble of several areas in and near Carbondale, Illinois, including some of Grand Tower, Illinois.

The 2018 Richard Peterson Poetry Prize, Jack Dyer Fiction Prize, and John Guyon Literary Nonfiction Prize We are pleased to announce the winners and finalists for the 2018 Richard Peterson Poetry Prize, Jack Dyer Fiction Prize, and John Guyon Literary Nonfiction Prize. In poetry, the winning entry is “Cholera Is What My Grandfather Did During the War” by Esther Lin of Jackson Heights, New York. The judge, Allison Joseph, selected two finalists in poetry, and they are “Elegy or When Daughters Drown Their Fathers” by Lauren Alleyne of Harrisonburg, Virginia, and “In Times Such as These, We Find We Must Make Do” by Josephine Yu, of Tallahassee, Florida. In fiction, the winning entry is “Fish Boy” by May-lee Chai of San Francisco, California. The judge, Allison Joseph, selected two finalists in fiction, and they are “Out of Sofya” by Amanda P. Hartzell of Seattle, Washington, and “Between the Waves” by Emory Noakes of Columbus, Ohio. In literary nonfiction, the winning entry is “Teaching the N-Word in Georgia” by Kerry Neville of Milledgeville, Georgia. The judge, Allison Joseph, selected two finalists in literary nonfiction, and they are “The Fabric of Peace” by Jennifer Lang of Raanana, Israel, and “Present Progressive” by Catherine Mauk of Higgins, Australia Capital Territory, Australia. All three winners received $1,250.00 and their works are published in this issue. All of the finalists also chose to have their works published in this issue and each received $200.00. Congratulations to the winners and finalists, and thanks to all the entrants for their interest in Crab Orchard Review.

The Winners of the 2018 Richard Peterson Poetry Prize, Jack Dyer Fiction Prize, and John Guyon Literary Nonfiction Prize

2018 Richard Peterson Poetry Prize Winner

“Cholera Is What My Grandfather Did During the War” by Esther Lin (Jackson Heights, New York)

2018 Jack Dyer Fiction Prize Winner

“Fish Boy” by May-lee Chai (San Francisco, California)

2018 John Guyon Literary Nonfiction Prize Winner

“Teaching the N-Word in Georgia” by Kerry Neville (Milledgeville, Georgia)

May-lee Chai Fish Boy “Hey, kid, you just gonna sit there?” the Boss was standing in front of

Xiao Yu. Xiao Yu recognized the man’s polished leather shoes, the cuffs of his expensive pants, his complicated watch, the clean white cuffs of his shirt. Out of politeness he’d never stared the man in the face. Now Xiao Yu stood up and stared at the man’s shoes. “No, Uncle,” he said politely as his grandfather had instructed him to say. “I can work, too.” “Work?” The Boss laughed. The men in the kitchen laughed. “The squirt wants to work, did you hear that?” The Boss put his hand on top of Xiao Yu’s head. He could feel the sweat of the man’s palms dripping through his hair to his scalp. “And what can you do, Squirt?” “I can scale fish. I know how to kill chickens. I can—” “Whoa, whoa, listen to this! The Squirt really does want to work!” The Boss laughed. He pulled a pack of cigarettes out of the pocket of his crisp white shirt and tapped one out for himself. “Fine, fine, glad to hear you can be useful. Country kids, much better than a city brat,” the Boss said. “A kid who’s willing to work.” He tapped one of the men with the cleavers between the shoulder blades. “You! Show the kid how it works with the fish. Kid wants to scale fish, let him.” Xiao Yu’s heart jumped inside his ribcage. To earn real money! The Boss headed toward the door. He turned, jabbing his cigarette in the air at Xiao Yu’s nose. “Show me what you’re worth, kid, and maybe I’ll hire you, too.” Then he opened the door—the sound of a woman singing a Hong Kong pop song momentarily flooded the kitchen along with a thousand dots of colored light from the mirrored disco balls—then the Boss was gone and the door swung shut. “Fuck his mother! What am I supposed to? Babysit?” the man with the cleaver spat on the kitchen floor. “I know how to scale—” “Yeah, yeah, yeah. You know everything. I heard you. But this is the city. Things are different here.” The man sighed. “Come with me.” He led Xiao Yu to a little room just to the side of the kitchen where the walls were lined with fish tanks. Just then one of the waitresses dressed in a shiny red qipao slit to her thigh hurried in. “Give me a grouper, quick! Make it a big one.”

Crab Orchard Review

u

1

May-lee Chai The man grabbed a net and fished a grouper out of one of the tanks and slipped it quickly into a yellow plastic box, where it flipped and flopped, gasping for breath. “That good enough, Little Sister?” “Watch your mouth. I’m not your sister,” she said, and picked up the box and took it outside. “All right, kid, now do you remember what that fish looked like?” “Yes. It’s a gray fish with dark spots—” “Yeah, yeah. I mean, the size? You think you could find its twin?” “All groupers look like that.” “Fuck. This kid is straight off the farm.” The man shook his head, but he took Xiao Yu by the shoulder and led him down the line of tanks, past crabs and lobsters, past lively colored fish that shone like gemstones, to a row of tanks packed so full of fish they could barely move. Many were ill, graywhite fungus growing from their gills, floating listlessly on their sides, their fins beating the dingy water futilely. “Find the grouper in this tank that looks exactly like the one we put in the box, and be quick.” “But none of these fish look like that one. These fish are sick—” “They’re okay, they’re going to die soon anyway. Consider it a blessing to kill them. Do you believe in the Buddha’s teachings?” “The Buddha?” The man shook his head. “Never mind. Just find the fish. Hurry up.” Xiao Yu scanned the filthy tank. The sides were covered with algae, even the light bulb under the lid was covered with a greenish growth. “That one’s the same size.” “Get it then.” The man handed a net hanging from a nail on the wall to Xiao Yu. Xiao Yu lifted the lid gingerly and peered into the densely packed tank. He stuck the net in, trying not to accidentally scoop up the wrong fish, but it proved harder to net the large grouper that was floating on its side slowly up and down towards the back of the tank. Other fish kept bumping it away or swam into the net. Xiao Yu had never seen such sick fish. Finally, he dropped the net onto the floor and rolled up the sleeve of his good sweater, the one his grandfather had insisted he wear to their first week of work, and stuck his right hand into the brine. He was able to grab the sick grouper by the gills and pulled it up. “Hey, that’s a useful trick.” The man nodded approvingly. “Here, put it in this bag.” The man grabbed a plastic bag from a pile on the shelf under the tank and held it open so Xiao Yu could slip the grouper inside. It barely flopped at all. The only sign that it hadn’t died yet was the way the plastic was sucked into the fish’s gills as it tried to breathe, suffocating slowly in the dry air. Suddenly the waitress reappeared and set the yellow plastic box on the

2

u

Crab Orchard Review

May-lee Chai ground next to the tank of healthy fish. “They want it steamed with garlic, ginger and chives. No hot sauce this time.” She ran out again. The man lifted the box and quickly dumped the lively grouper back into the clean tank, where it flipped once, twice, and then began to swim rapidly back and forth, as though it thought it might be able to swim away and escape. “You heard her. Show me how you kill a fish now, clean it, and then I’ll show you which cook to give it to.” “Won’t the customers get angry?” “They’ll be too drunk by the time they get to the fish course to even notice.” Then the man winked at Xiao Yu in a way that made him feel older, a part of things. Clever like these men, not like city kids who didn’t know how to work, like the Boss had said. Not like a kid at all really. And Xiao Yu squared his shoulders and stood a little taller. After he’d been cleaning fish for four hours, Xiao Yu’s shoulders ached from hunching over the bucket where he was told to dump the scales and the guts. The smoke from the woks and the men’s cigarettes made his throat burn. Fatigued, the men had stopped yelling jokes and obscenities at each other. It was as if the night were flipping on its belly like the fish in the filthy tank. Trapped amongst the other men, Xiao Yu felt the kitchen growing smaller, closing in on him, too. He imagined stretching out on his bunkbed in the dormitory. It would feel good to be able to stretch at all. “Hey, kid, time to empty the buckets. We’ve got to get rid of this smell. Smells like a toilet in here. From now on, don’t wait so long. Throw the guts out back in the trash before we’ve got piles building up. This isn’t some farm.” Xiao Yu bristled at the man’s insult, his cheeks burning hot, hot. He wanted to take his fish knife and hook the man who’d insulted him. But he thought about his grandfather, and the money they’d be making, and maybe they’d be able to hire a real lawyer for his father—he wasn’t supposed to have heard about that, but he’d overheard his grandparents talking when they thought he was asleep on the train. If they could hire a city lawyer, his father would be all right. They just needed more money. Xiao Yu would show these men then. He’d expose their corrupt restaurant to the police. With their rotten food and their dirty tricks. He’d show them a country boy wasn’t so stupid after all. But for now he picked up four of the buckets of guts, two in each hand, and carried them to the back door. He wasn’t afraid to work. He’d make his family proud. The night air was cool against Xiao Yu’s flushed cheeks. When they’d first arrived in Zhengzhou, he’d found the air gritty, strange, with a smell so different from the village air that he had pretended in his head that he was a taikonaut, the first Chinese on the moon, and he was walking in a heavy white suit with a fishbowl helmet over his head. The air he was forced to breathe, recycled and

Crab Orchard Review

u

3

May-lee Chai coming from tanks on his back, smelled like Zhengzhou’s air. Like air that had already been breathed in and exhaled by nine million people. But after four hours in the smoky kitchen squatting over the buckets of fish guts, he found the night air no longer smelled so bad. It wasn’t country air, but it wasn’t kitchen air either. He put the buckets down for a second and allowed his weary lungs to breathe deeply before he set off for the dumpsters. He closed his eyes, listening to the distant sounds of traffic, horns honking, voices of invisible people arguing and laughing, a bus rumbling by on the street beyond the alleyway. Then it was time to get back to work. Xiao Yu was gingerly pouring the first bucket’s bloody contents into the dumpster in the dark alley behind the restaurant, when a ping! like the shot from an air rifle ricocheted off the dumpster’s metal side. He turned around immediately. There was a group of boys on bicycles, fancy bikes, the kind he’d seen on TV, the kind you could do tricks with: wide tires, low handlebars, bright colors. City bikes. “Hey, Little Rabbit, what’s up?” Xiao Yu eyed the four boys arrayed between him and the door of the restaurant. They were older, high school students, he guessed. And there were four of them. He didn’t want to speak, afraid his accent would give him away. “What’s the matter? You a mute?” The tallest boy approached. The others circled closer. Xiao Yu put the bucket down and wiped his slick hands on the sides of his pants, even though they were his best pants and he wasn’t supposed to get them dirty. He’d been very careful in the kitchen actually, leaning far over the buckets so the guts wouldn’t splatter. Finally, one of the cooks had given him an apron and he’d spread it carefully over his pants, purchased by his father from the city just for this trip, so that he’d blend in with the other city kids. He’d been proud. Proud to have new clothes, even if they’d been purchased to make it easier to hide, so police wouldn’t spot them on the streets, the way they imagined, and send them back to the village. They hadn’t realized how little anyone in the city would care about their appearance. “You look like a young man now,” his grandfather had said proudly, seeing Xiao Yu in his new clothes. “No one will know you haven’t grown up your whole life in a city.” All these thoughts circled through Xiao Yu’s mind as he eyed the boys. “What’re you doing here?” A boy with a round face and flat nose pointed his chin at Xiao Yu. He had extremely small eyes, making his face seem more pig-like than a normal human’s. The tall boy stood back now. Xiao Yu figured he was the leader. The other two boys were thinner, acne dotting their cheeks. As they approached, Xiao Yu could see they chewed their lips. They were cowards. They would be the ones he should attack first if it came to that. It was going to come to that. He felt the hair on his neck rise. He could feel the sweat pouring from his armpits.

4

u

Crab Orchard Review

May-lee Chai “This is our alley. What are you doing here, Little Rabbit?” “I work for the restaurant. The boss told me to—” The boys charged. They were faster than he thought. The two skinny ones grabbed him from behind, twisting his arms up into the air behind his back, the pig-eyed boy punched him in the stomach. Xiao Yu thought he might throw up. The alley turned completely black. Now the boys were kicking him. He couldn’t even call out. The nausea was overwhelming. He retched. He hadn’t eaten all night, there was nothing to throw up, but he retched again. The tall boy came over and he felt hands going through the pockets of his pants. “No money. This tu baozi is as poor as he looks.” He felt the boy’s spit land on his face. Then the boys were kicking him, he curled into a ball. “Hey, hey, watch this! Watch me!” Pig boy’s voice. Suddenly Xiao Yu felt wet slimy entrails raining down upon his head. Laughter. The blood made him want to retch again. But something about the cold fish guts revived him. His vision was returning. The city boys were bent over laughing. They were turning away, going to their bicycles. Xiao Yu felt along the ground searching for a rock. He had good aim. He could make a stone skip thirteen times atop a fish pond. He wouldn’t miss, even now. But he could find no rocks. The boys were retreating. Then Xiao Yu’s fingers felt the beer bottle. It was broken, empty, rolled beneath the dumpster. He gripped it tightly. He staggered to his feet, and with the adrenaline and anger just enough to make him dangerous, he found he could run. He ran towards the city boys and lobbed the bottle as hard as he could at the back of the tall boy’s head. It struck, shattering against the tall boy’s skull. The tall boy dropped his bicycle and clutched his head with both hands. “That mother fuck!” The pig-eyed boy turned towards Xiao Yu. “Beat his balls off!” the tall boy gasped. Blood, black in the dim light, gushed from between his fingers. “Fuck your mother, Rabbit Boy!” The skinny boys rushed him. Xiao Yu retreated to the dumpster and one of the boys slipped on the spilled fish guts. Xiao Yu managed to punch the other skinny boy in the face, but then Pig Eyes grabbed him tightly, wrapped his arms around his chest, squeezing so that Xiao Yu couldn’t breathe. He thought his back would break. He shouted now. He howled. “I’ll fuck your mother and your grandmother!” Pig Eyes slammed Xiao Yu against the dumpster. Xiao Yu’s head struck the metal with a loud thunk.

Crab Orchard Review

u

5

May-lee Chai “Cut his face.” The tall boy approached, his left hand still holding the back of his head. In his right hand he held a piece of broken glass. “Hold him still and I’ll cut the fucking eyes out of this bumpkin’s head.” Xiao Yu felt the boys’ hands around his arms and legs, around his neck, as he tried to squirm free, but Pig Eyes was big. He leaned his weight into Xiao Yu, setting a knee on his chest. Then all at once a triangle of light flooded from the open kitchen door. “Hey, you little bastards, get the hell away from here!” One of the cooks had come out to see what was taking Xiao Yu so long. He was carrying a cleaver. The light behind him, he appeared in silhouette, as black as the sky. “My father will put you in jail. Do you know who I am?” the tall boy shouted back. “You’re going to be tonight’s main course if you don’t get your junior high ass off the Boss’s property! Do you know who owns this restaurant?” “My father will have this restaurant closed down! My father will have all of you thrown back to the countryside where you belong! My father—” “Your father’s going to bury his son in a paper bag.” The cook turned back and shouted something into the restaurant. A burly man with a bald head and a large tattoo on the side of his neck, spiraling up the side of his check, appeared. “You have no idea who you’re talking to. You’re just workers.” The tall boy tried to laugh, but even to Xiao Yu’s ringing ears, his voice sounded less confident. The burly man didn’t stop to talk, he approached the boys rapidly. They backed away from Xiao Yu, standing away from the tall boy, too. Xiao Yu watched the world from the asphalt, through his one eye that wasn’t swollen shut yet. The burly man went right up to the tall boy and pulled out something shiny. Xiao Yu thought it might be a knife. He pointed it at the boy’s face. “You wouldn’t dare. My father will—” The man pointed the shiny object at the brick wall beside the restaurant and fired his gun. It was louder than any gun Xiao Yu had ever heard. In the countryside, when men hunted, the sound of gunfire was absorbed by the huge open sky, not like the sky here, which was small and distant, trapped between buildings. Lights turned on from the windows at the tops of several buildings. But more lights went out. The man pointed the gun at the tall boy’s face and pulled the trigger. Even Xiao Yu could hear the click. Unmistakable. But there was no bullet. The man cocked the gun once more. The man said, “Do you think I have another bullet or not, little shit?” The boys took off running. They ran to their bikes, jumped on them, and rode off into the night.

6

u

Crab Orchard Review

May-lee Chai The burly man re-entered the restaurant. Now two of the cooks returned. Xiao Yu recognized them from the smell of the garlic and cigarette smoke on their skin. His vision wasn’t so good anymore. The world was a blur of light and shadow and more shadow. “Look what those little hoodlums did to the fish boy,” he heard one say. “He’s fresh from the countryside, this one. Has no idea how the city operates.” “Hard worker though.” “All right, help me pick him up.” Xiao Yu felt the men grab him under his arms and drag him towards the light coming from the open kitchen door. He recognized the smell of smoke billowing into the night air. The two men stopped to inspect him. “He doesn’t look that bad. He’s just beat up a bit. Still got all his parts.” “Hey, you’re lucky,” one of the men shouted into his ear. “My shoes. They took my shoes.” “What? What was that?” “Don’t try to talk, kid. Not tonight. Give it a few days.” “My good shoes,” Xiao Yu tried again, but the men couldn’t understand him. That night he didn’t have to gut any more fish. The Boss came in briefly; he could tell from the man’s voice and the way the kitchen grew quiet when he entered. Someone gave Xiao Yu a glass of hot water and some pills to take. Then one of the cooks helped him to wash in the kitchen staff’s toilet. It was a filthy room, the toilet was stopped up, and the whole room smelled of urine. Xiao Yu barely moved as the young cook washed Xiao Yu’s face, splashing water from the sink on him, over and over. The water was cold. It hurt and it didn’t hurt. Everything hurt and nothing hurt. His body was throbbing, beating along with his heart. He was floating. He was watching this shadow self covered in blood and fish guts slumped against the wall in his underwear, this boy being doused with water from the rusty pipes. Xiao Yu thought of how clean his grandmother had kept their indoor toilet back home. She would never let any room in their house become this filthy. They lived like civilized people. Xiao Yu remembered his father supervising as the men had put in the pipes, then the sit-down toilet, even the shower, with the water heater so they could have both hot and cold water inside their home. Their house was clean. He would never walk into anyone’s home with his shoes on. Here, people wore their shoes on indoors all the time. In the dormitory, he’d seen men sleeping in their shoes even. Xiao Yu had never imagined that city people would be so unclean. “Hurry up, kid. There’s blood everywhere. Don’t just sit on your ass all night.” Xiao Yu jumped up from his stool beside the bucket over which he gutted

Crab Orchard Review

u

7

May-lee Chai the fish and grabbed the mop from the storeroom beside the smelly, bubbling, overpacked fish tanks. Seven months in the city and the filth no longer fazed him at work or in the streets or in the dormitory. Xiao Yu grabbed the metal bucket, filled it with water from the concrete sink there, and mopped up the entrails spilling onto the kitchen floor. Chicken guts, duck guts, goose guts, fish guts, snake guts, even lizard guts. (Lizard was the week’s special. Xiao Yu had never imagined the prices city people would pay to eat food a farmer would eat only in times of great famine. The cooks laughed about it and then shrugged.) Life in the restaurant had taken on a kind of sameness: filth and shouting, the same jokes, the same insults. The Boss barked orders at the cooks, the busboys, even a couple of the waitresses in their shiny, too-tight qipaos. The Boss’s cigarette butt dangled perilously over a dish of ma po doufu he inspected, before satisfied with his power, he pulled his pants up a bit—they tended to slip down beneath his bulging gut, like a pregnant woman’s, Xiao Yu thought—and rushed back out into the dining room to banter obsequiously with the drunken customers. “Ta ma de,” one of the cooks swore, tossing a heavy iron wok full of shrimp. The flames leaped up, following the oily wok, licking its round bottom. Nonchalantly, the cook tossed in a dash of spiced oil, steam emerging in a cloud, and set the wok back down over the possessive fire. The room soon filled with the smell of hot Sichuan peppers. “Whad’ya do that for?” Another cook coughed and spat on the floor. “Hey, kid, open the back door. We’ll all suffocate in here. That rabbit’s daughter is trying to kill us.” He coughed some more. “Ha! This is how you make Sichuan shrimp. You people can’t handle a little spice.” Xiao Yu set the mop in the concrete sink then carried the bucket of bloody water in one hand, the bucket of miscellaneous entrails in the other. He headed toward the back door, stopping only once to set the heavy buckets down for a moment, wipe his hands on his cotton pants, slip a knife from the counter into his pocket, a pack of cigarettes up his right sleeve, and then picked up the buckets again and headed out the back. He left the door propped open with a stone, just wide enough to let in fresh air—and so that he could hear the cooks arguing—but not so wide that they could see him make his way through the alley to the dumpster behind the restaurant. Four boys were waiting for him. “What took you so long? It’s cold out here.” “I could have taken a shit if I’d known you were gonna be so late tonight.” “What’s stopping you now? Wanna shit, go shit,” Xiao Yu shot back. Then he pulled out the knife and the pack of cigarettes. “That’s nothing,” one of the older boys sneered. “Tiny knife like that.”

8

u

Crab Orchard Review

May-lee Chai “Oh yeah?” Xiao Yu scratched the tip across the metal of the dumpster. It left an impressive scar. “Chef’s knife. Nothing sharper.” “Shit! How’d you get that?” one of the boys gasped. “Never mind. What have you got?” One of the boys pulled out a crumpled pack of Panda brand cigarettes and a whistle. The other boys including Xiao Yu groaned. “That’s nothing. Send that home to your grandma for Tomb Sweeping Day. She can leave it on the graves she sweeps.” “What about you?” The others brought out knives, a rusted cleaver, a set of tools— screwdrivers with different size heads and a few hammers, and a bottle of clear white rice wine. “That’s as small as your penis!” one of the boys sneered. “What are you looking at his penis for!” They boys laughed. The angry boy threatened to kick the mouthy one. They got over it. “Hurry up. I can’t stay out here forever.” “I’ll trade you my knife for the bai jiu.” Xiao Yu nodded at the wine. “No way. That’s genuine Maotai. Know how much that costs?” “Let’s drink it,” someone suggested. “Don’t be stupid. I could sell this for money.” “My knife and the cigarettes. They’re foreign. American brand. Smoother than Chinese. I’ve smoked them.” “They wouldn’t give you one.” “Sure did.” “Okay.” The boy handed the expensive, tiny bottle of liquor to Xiao Yu. He tucked it into his pants pocket. Then thinking better, tucked it into the hidden pocket his grandmother had sewn into the interior of his tee-shirt, just in case there was some emergency and a hidden pocket might come in handy. At the time, Xiao Yu had had no idea what she was thinking. Now he appreciated her guile. Before anyone could object or try to negotiate a better trade, Xiao Yu dumped his buckets into the dumpster and ran back toward the kitchen, leaving the other boys, all restaurant workers from the neighborhood, to bargain over the remaining loot. The next morning, Xiao Yu woke early as usual. His grandfather was snoring, exhausted from his night job. He slept like the dead, unmoving, his body stretched out straight and stiff across his bunkbed, dressed in his clothes. He’d been too tired to remove them after he got back to the dormitory. As usual. If not for the potent snorts and hoots that emerged from his nose, his grandfather could truly have been mistaken for dead, Xiao Yu thought. It

Crab Orchard Review

u

9

May-lee Chai was a good thing the other men sleeping here were just as exhausted or they might have complained. But in the dormitory they were all migrants, none of them with a legal work permit; no one complained about noise. Xiao Yu zipped his jacket and grabbed his shoes from under the bed, then ran out of the dormitory quietly. He didn’t stop running even as he slipped his feet into his sneakers, sprinting down the hallway that led to the toilets. The light was dim from the tiny windows. Not yet dawn but soon. The night shift workers had come to bed at four. The day shift workers would begin rising at five. He had the hallway to himself, the air reverberating around him with snores. The window opposite the toilets didn’t close properly. The men kept jacking it open, to mitigate the smell. It was the only window in the entire dormitory that wasn’t sealed and locked. Xiao Yu hiked it up easily, wincing at its squeak, but no one came from the factory or the toilet or the dormitory. He squeezed through the opening and dropped to the ground some six, seven feet below. The window was unsteady. It would squeak its way down soon enough, as Xiao Yu had discovered. Now he ran, as fast he could, but quiet-quiet, too, so as not to wake the guard dogs in the cages on the sides of the courtyard where the morning shift workers were required to gather for morning exercises or pep talks or simply to stand while being shouted at by the bosses through loudspeakers. Sometimes if a worker tried to leave his shift early, they’d stick him in the dog cages or make him kneel on the concrete in the sun as punishment, the dogs barking behind him. The bosses threatened to release the dogs if the man didn’t obey. The men always obeyed, however. Xiao Yu kept scraps from the restaurant in his pockets. If the dogs woke, he threw them the meat through the bars of their iron cages. They knew him by now. They wouldn’t bark long. The dogs were like men. They only worked because they were hungry. Xiao Yu made it to the end of the courtyard. The sky was lightening. Dawn was coming. Soon the drunk who sat in the gatehouse, checking the identification cards of everyone who entered or left the factory compound, would wake. Then there’d be problems. But now as Xiao Yu crept to the gatehouse and peered in its window he could see the man slumped over his desk, snoring into the crook of his arm. Xiao Yu slipped past him to the front gate, which was easier to climb over than the stone walls that had broken glass embedded in the cement on top, plus strands of barbed wire. Not that he hadn’t learned to scale those walls, but he preferred not to. Didn’t want to risk a tear in his city jeans, the pair he’d bought with his own money. Now he climbed the metal bars of the front gate, and hauled himself to the top where the bars turned to sharp spikes. He balanced on the horizontal metal beam, careful to fit his feet between the spikes. This was the tricky part. If he lost his balance, he’d fall twelve feet to the concrete below. Or worse, if he slipped just a bit, he’d fall upon a spike. But Xiao Yu didn’t slip. He never even worried

10

u

Crab Orchard Review

May-lee Chai that he would. It was too exciting to escape the dark, snore-filled, fart-filled, old-man-smell-filled dormitory and roam the city streets and alleys. He was almost fourteen. There was nothing he felt he couldn’t do. Xiao Yu ran through the streets. There was already traffic. There was always traffic in the city. People working, getting off work, going to work, stumbling from bars, stumbling into bars, lurching about the sidewalks, strolling with friends, running from enemies, sidewalk vendors, small shop owners, big club owners, farmers in tattered clothes selling fruit from baskets, beggars, pickpockets, gamblers, hookers, foreigners, buses, trucks, taxis, cars, even a few bicycles. He met up with his new city friends in the alley behind the department store with the giant billboard of some Korean movie star smiling in front. The boys were already well into their game. A pile of crumpled bills, bartered weapons—knives, cleavers, rusted pointed things—foreign candy, favorite snacks, and a watch lay in the middle of the circle of boys as they tossed their cards down, grabbed others. Then the boys compared hands. Much groaning, and one boy swept up the pile into his knapsack. Another boy began dealing a new round. He flipped the cards expertly. Big Ears’ skill was a thing of beauty. His hands, normally thick and stubbyfingered, dirt under his nails, became as graceful as a Wushu artist’s, as fast as Jet Li, when he shot the cards through the air. “Are you in?” one of the boys asked without looking up. He rearranged his cards. Xiao Yu threw down a few of the bills he was paid by the boss for gutting fish and other animals all night. “Of course I’m in. Prepare to lose.” “Ha! You don’t have the money. You’ll fold before we get to the third round.” They laughed, they swore, they shared some stolen cigarettes and a can of Coca-Cola mixed with a bottle of cheap bai jiu. Xiao Yu was never more aware of how useless his schooling had been, all those years memorizing all those worthless characters, reading those old boring essays, when the real world was out here, on the street, made up of money and fast hands, faster feet. This life was an education. His old life was like a long dream, one only his grandfather still believed in. The dream of school and his father returning from prison and the family together in the village. If Xiao Yu thought of such things at all, it seemed to him his entire family was living in a coma. Only he was awake. When Xiao Yu returned in the afternoon, after shoplifting with his friends, extorting money from younger kids on their way to and from school, or fighting with rival gangs, he never told his grandfather about his real life, about the real world that Xiao Yu had discovered and now inhabited and intended to learn how to survive in. No, how to thrive in. He was a good student after all. He’d just been studying the wrong material.

Crab Orchard Review

u

11

May-lee Chai When he returned to the dormitory, brazenly walking through the front gate this time, bribing the afternoon gatekeeper with some of his day’s earnings, Xiao Yu would tell his grandfather that he’d been to school. It was only halfday because he was a migrant in the city, no residence permit, so he had to go to a charity school run by some do-gooders but at least some schooling was better than none. And his grandfather would smile, the folds around his eyes deepening, the happiness on his face evident. He would pat Xiao Yu on the head, “Study hard. Be sure to study hard for your father. He’s worked all these years just for you.” And Xiao Yu would nod and pretend to be both astonished and thrilled by the crumpled ten yuan note his grandfather would slip into his hand, with a wink. “Be sure to buy yourself a snack after school tomorrow. Something the city kids like. You might as well get used to this lifestyle. Learn what it’s like. No point acting like an old man before your time.” Xiao Yu nodded. “Thank you, Ye-Ye,” he said. “You’re my grandson,” Ye-Ye replied. “I want you to have the best. Remember you’re just as good as these spoiled city kids. Better. You know how to work harder.” Then he quoted the proverb about fish and birds: a fish is bound only by the sea, a bird by the sky. It was supposed to mean Xiao Yu could go far in the world if he put his mind to it. Xiao Yu would hang his head, stare at his sneakers, feigning modesty. But truly he thought his grandfather was correct. This was the one point where they indeed saw eye to eye. Xiao Yu knew that he was as good as these city boys, better even, because he saw more clearly than they. They were fish in a bowl, only he had leapt into the sea.

12

u

Crab Orchard Review

Lauren K. Alleyne Ugly I hate the thing in me that hates the dog— her dumb stare, vacant, or else filled with some unknowable doggish emotion. I recognize some looks— shame’s slink and slide; joy’s wide roll, the squint of obstinate pursuit— at odds with the furred canvas of her face. I hate how I relish the potent drug of mastery, the high of her unquestioned obedience, her quickening at my barked commands —Come! Sit! Go to bed! I hate when she forgets which of us is boss, which dog, hate how I bring the whole power of me to bear upon her small rebellion, her helplessness at the odds so stacked against her when I lift her whole body up, put it where she will not go. I hate her cower at my descending hand, but relish the measured thud of justice against her backside for fouled carpets, the labor of laundry. I hate the old pantomime of it all —the shackles of need,

Crab Orchard Review

u

13

Lauren K. Alleyne the thin leash of duty, the humiliations we bear and burden each other with in the name of some hunger we call love.

14

u

Crab Orchard Review

Lauren K. Alleyne

Elegy or When Daughters Drown Their Fathers

You do not do, you do not do anymore/black shoe —“Daddy,” Sylvia Plath after Patricia Smith and Tiana Clark You cannot ask a pond to be an ocean, an anthill to be a mountain, or rather you can, but you will be disappointed — resent the pond’s visible shoreline, crush the un-awesomeness of the anthill beneath your tantruming feet. You cannot ask a man to be more than the sum of his history and desires, more than his silences filled with a dead father & six siblings & the breakback work that crushed all dreams of high school or dreaming. You, daughter, want skyscrapers & degrees & nothing his hands understand & hate him when he offers in his slow, black drawl the song of why and wait. You purge him like a poison, cut your eyes at his face in yours—you, daddy-in-drag, wearing his small-toothed smile, his dark face. You stomp no on any anchor, refuse any limit but the horizon, rename yourself

Crab Orchard Review

u

15

Lauren K. Alleyne endless, and him, outgrown; you bury him with the bright blue mists of your future,  set sail and never look back.

16

u

Crab Orchard Review

Lauren K. Alleyne

She who wears horns and weeps (A lament in two voices)

1. Hera They call him thunder, but he falls like rain at the sight of any female flesh—any rouged lip, curve of hip, any flash of nipple, pink of tongue. I would incinerate his immortal cock, harvest his balls like ripe figs, but my eternity is bound to his by the fat lashes of heat and heart: I am cursed to love the thirst of him.

2. Io For love of me, he held me face down in the grass. He summoned a cloud to pillow my head as he pushed himself between my legs. I said I was a virgin, sworn to serve his jealous wife, Hera, and he came, a burst of god seed. For my safety, he changed me again, made a new beast of me.

3. Hera If they are his meat, I will carve them to bone and shadow before him. If they are water, I will dam them, poison their wells. If they are the pleasure of his eyes I will monster them. What is luminous I will gutter; what is peaceful I will ache, as I ache: to madness.

Crab Orchard Review

u

17

Lauren K. Alleyne

4. Io A gadfly, Hera? Buzz and bother? I can no longer walk upright. I have no arms to hide my shame. I lost laughter and human tears; I grieve in a foreign skin. I cannot wash his slick from my body, his grunts and moans as he fucked me, wild with his lone passion—; wings and sting to punish me, Hera? As if.

18

u

Crab Orchard Review

Idris Anderson Sugar House After November’s slaughter of animals, what all wouldn’t we do for a little sugar? The mule named Lucky walks round and round the big mechanical contraption. Harnessed, leather collar and straps, he carries the long boom at his heels. No one forcing him to go or stop. Uncle Eddie feeds stalks of purple-green cane to the mouth, the teeth of the machine, not too much, not too little. He remembers each time to duck under the boom. Cane juice pours green from the gears. The boom moves steady like the hand of a clock. Grinding, grinding, the hard breaking press and crack of the cane. Barrel filling. The heavy hooves of the mule are digging a furrow. It takes three men to pour easy from the barrel, the great iron basin wide and shallow. No dripping. No splashing. The basin’s round bricked-up square, an opening in the back for fire underneath. A furnace. Stoked. Chimney smoke. Moon disks forged to long handles, big perforated ladles for stirring, for checking the thickness of simmering juice. Ladles lift, held dripping, sunk again, stirred and lifted. Women’s arms up and down, up and down, black, white, and brown, sleeves pushed up. Not yet syrup, not yet, though juice steams. Elijah, an old dark man, rakes out some coals to keep the fire from roiling. I was one of the children ready with strips of cane, like knives, like spoons, waiting for candy to gum and crystal on the edges.

Crab Orchard Review

u

19

Idris Anderson Decades later I stand small in the nave of a grand cathedral reading a stained glass window of martyred saints: a man—or is it a woman?—sits calm in a cauldron, arms lifted, flames or tendrils of steam arc higher as flesh boils, lights shooting red and blue through her, and I understand the fiery furnace of hell’s mouth, the heat of the cauldron, the sweetness of her suffering. Fire licked shadows on our faces as we knelt around the rim of the sugar cauldron. We were told to be patient, not yet to touch, to listen— the deep voice of the old Negro with white whiskers singing as he fed oak logs to the fire: Lordy, won’t you come by here. Angel locked the lion’s jaw. As ladles dripped sugar thicker and thicker, the singing settled us and made us feel something like worship or shame.

20

u

Crab Orchard Review

JosÊ Angel Araguz Selena: a study of recurrence/worry Somebody died and it’s okay to be Mexican. No, really, this is good. I was worried nobody would understand what it means to come from a city named after the recurring body of a martyr. No, really, this is good. I worried a whole generation of young women from a city named for wounds and resurrection would suffer themselves to be stilled and lost. Now I worry a whole generation of friends close their fists around empty beer cans and walk out the door to become lost, distilled memories. You would think no one would sing here again. That with beer cans in their fists mothers would tell stories about a ghost appearing should you sing here in this city, should you ever go onstage, a whole generation of mothers telling stories where not a ghost but a microphone vanishes directly below a spotlight that burns anyone who walks onstage, different moon in a different sky where it is always night. See, a whole city vanishes below the spotlight of my erratic memory. Corpus Christi, my imagination paints you as an indifferent sky where night after night we tell stories about who we were. You are more than my erratic memory and imagination, more than the name of a wounded, returned body. When at night I tell stories about Selena, I know that it is more complicated than

Crab Orchard Review

u

21

JosÊ Angel Araguz the name on a statue, more complicated than somebody died, and it’s okay to be Mexican. I know life is more complicated than anyone can understand or hope to become.

22

u

Crab Orchard Review

José Angel Araguz

St. Peter to Joseph St. Peter to the painter Joseph: Make an image of our Lord so that others upon seeing may believe. And later: Make an image of me so others can say this is the one who preached His word. I imagine Joseph before his materials, a uselessness felt keenly in his hands. Not knowing much about faith, only how to follow through in the way of all such stories that mix up acts of creation with the slight, airy fortune of creatures, I hear him ask inside himself how to proceed, ask, as I’ve asked, and, hearing no answer, have to ask again, until questions begin to blur as heat at the far end of a road makes the horizon appear water, water one would drink, pooled and shifting the closer one gets – ask and remain only able to take what he has into himself.

Crab Orchard Review

u

23

JosĂŠ Angel Araguz

Sentence When the piper leads the children off, the sounds of music and laughter die, and the parents are left with silence germinating in the open fields, land there is now too few hands to work. Silence sets a place for itself, sits at the table, waits as grace is said. Silence leaves nothing to scrape clean from its plate. Silence, true to itself, lets parents speak, unhindered. When silence overgrows, they kneel, same as praying, to weed it out, but leave in the root. Silence, their fear to slip and break, hurt, and not get up. Silence, they broom, stir, whisk through an open door in clouds, then later find again. Silence, they drink against. Silence, they lie awake, shift, every night, from darkness to darkness, ears, dehiscent, open to a far corner, where a scrap of onion skin turns in the small, clean hands of a rat.

24

u

Crab Orchard Review

Jacob Boyd One Looks at Two “…Across the wall, as near the wall as they. She saw them in their field, they her in hers.” --Robert Frost, “Two Look at Two” It is not for me to imagine what passes Between a cow and a Pekinese noticing each other In the spring snow, across an electric fence; Their paths of thought, As one advances and the other shies away, Diverge along a shared animal plane—the same Field of impulses in which my brain Arranges symbols into words I can’t use. Their thoughts are lost to me, who thinks More abstractly and, if not faster, farther Down causation’s fuse—concentrate, I say, Do not leap, but see each way you turn A thousand paths of song and choose One; the only way To praise what I saw in these two creatures Is to say what can be verified: they met And very soon moved on, not barking Or mooing, though the Peke glanced back As she went bounding down the stubble rows, And the cow kept her shield-shaped face Aimed at the dog’s wake. No dialogue Intervened—none but our three Sets of prints, which the snow seemed To compose for us, carried away as we were.

Crab Orchard Review

u

25

Anne Champion I Want to Marry a Communist Over Cuba Libres, in outdoor bars pulsing with Latin music, I fall in love with revolution and with my tour guide, his country’s myths weaving images of green fatigues and rifles, men who don’t bathe, whose sweat smells like a storm brewing. I have sex dreams of Karl Marx, lust knotting in my bones and unhinging my joints, so when my guide takes me in his arms and sways me like wind, I nearly collapse— Salsa’s easy, my dear, but you’ve got to let everything go. Everywhere I travel, I’m told I’m lucky to be American, and yet I feel stiff, shackled to this identity, coughing up the toxins of all the true histories and the false ones I had to unlearn. My tax dollars, blood money. My privilege, a pedestal that towers over racism, slavery, wars. My guide gives me a cigar and I know not to inhale, just let my tongue lick the smoke, taste the rich fragrance of death but don’t let it take root in my body just yet. I wish I could believe in love as liberation, trust it to buoy this weight, the way children fling themselves at waves, secure that the salted sea will lift their bodies,

26

u

Crab Orchard Review

Anne Champion brazenly rebellious against threats of undertows, the way the young women in Havana, propped on the ledge of the Malecón, wrap their legs around their lovers’ torsos, knowing a wave might hit, willing to test their luck like gambling addicts, betting the house, taunting the sea as they fling their hair like dice, ready to march home drenched in defiance, peeling off each other’s wet clothes and drying them for the next day on the ledge, even if the waves have swiped their purses and hats, even if they’ve lost everything before.

Crab Orchard Review

u

27

Martha Christina Closed He stands in the middle aisle of his family’s shuttered three-aisle department store, where the two Marias crowded each other, eager to spend their Christmas bonuses; where Isabel from the bakery lingered over the lace handkerchiefs, her curls springing up again after a morning’s constraint in a hair net. Angela, his mother’s second cousin’s wife, paid cash for everything and loved blue sweaters, any shade. Her sister, Trina, more selective, didn’t like to be hurried. Don’t rush Trina, he says, aloud.

uuu

Days when St. Rocco’s students were measured for their uniforms, he needed extra help. That’s how Virginia came to clerk for him, just helping out, temporarily. He watches her box children’s anklets. You’re a good worker, he calls to her, maybe my father will give you a raise.

uuu

Virginia watches him straighten

28

u

Crab Orchard Review

Martha Christina a sweater on the shoulders of the nearest mannequin. She remembers the strength of his hands, how he held her against the wall in the stockroom, sixty years ago.

uuu

He moves up the aisle to the locked door, turns the cardboard “Closed” sign to “Open,” turns to her and smiles. Ready? he asks.

uuu

She’ll have to tell him, again.

Crab Orchard Review

u

29

Renee Evans Absentia Annie closes the door to her daughter’s tiny and neat room, the

one that looks immediately out onto the train when it flashes by. Stephanie is supposed to be in her room right now, but she is not. Annie swallows and swallows again to be rid of the panic and understands Stephanie’s absence as her own fault: since the divorce, Annie has acted unpredictably—maybe even irrationally—and immature. Stephanie, not Annie, chose this apartment because it was the only one within their budget (she established a budget for the two of them when they first moved to Chicago eight months ago, and it didn’t include any more shopping sprees for Annie or for herself—she could be so much like her father sometimes); Stephanie scolded Annie for shoplifting fingernail polishes from the Walgreens down the street (she didn’t make her take them back, thank God) and told her to knock it off; Stephanie mandated they eat together at least five days a week, and she created and enforced the no-televisionduring-dinner rule. It’s just too much to ask a twelve-year-old to be the adult, Annie should know. And no matter how much she wants to be Steph’s friend— her best friend—and keep her as constant and as close as skin, she’s only going to screw it up. And now Stephanie is gone. Annie has failed. Of course she failed, they will say. No discipline. No authority. What kind of mother is that? “Steph? Honey?” She calls back down the alcove that would be a dim hallway if this were a real apartment and not a rough collection of a halfstove, a bathroom-ette, a pocket for couch-space, and three walls and a door meant to serve as the “one-bedroom”—enough space for Stephanie’s twin bed and bookshelf. Annie calls again. Not even she is convinced by her attempt to keep the terror out of her voice. She just stepped out, not even two blocks down, for cigarettes. Tom’s going to kill her. This is what Annie gets for lingering so long in front of the liquor store. But she didn’t buy anything this time; she kept walking, eventually. When she left, Steph wasn’t supposed to be abandoning her mother to a cold and unfamiliar city that didn’t turn out to be the adventure she originally thought it would be; she was supposed to be finishing the dishes, not running away. Dear God, what if she’s running back to her father? Tom and Steph get along well enough; they’re both so stingy. But Stephanie’s got something her father doesn’t. There’s a maturity to her, a sense of moral awareness that Tom (Annie, too, if she’d admit it) doesn’t have. And doesn’t Steph know that Annie needs her? Even if it’s just to get her to sit down and share a meal.

30

u

Crab Orchard Review

Renee Evans It was a nice dinner: some tuna thing out of a box they spruced up by adding frozen peas and parmesan cheese. Stephanie stood over the sink, frowning as she drained the can of tuna. She said, “You know who this rust stain in the sink looks like?” Annie stopped stirring the boiling noodles and peeked into the basin. “Abe Lincoln?” “I was going to say Barbra Streisand, but now that you mention it… maybe if you’re old and unimaginative and can’t see very well. It might be him. In the right light.” “Smart-ass,” Annie said, and swatted her daughter lovingly on the behind. “Dumb bunny.” One more thing I’ve screwed up, Annie thinks, as she races back down the four flights of stairs and to the car. First Tom and now Steph. And once she gets down to the car, then what? Where does a woman search for her runaway daughter? She doesn’t know, doesn’t buckle up as she almost simultaneously starts the car and throws it into reverse. The train whistle sounds overhead. Fucking train. She hasn’t had a decent night’s sleep since they moved here. She turns right out of the parking lot and heads toward downtown. She sighs. She might have fought harder to keep Tom. He simply handed her the papers one day and said he’d had enough. He said that she used her childhood as a crutch (so her mother neglected her, her brother abused her; he didn’t see why she couldn’t get over it), that she was addicted to pitying herself. That she was selfish. He’d said it before, and Annie had learned to hate that about him, but she trusted he would be there always; that was one of the things she counted on him for: his steadiness, even if he did turn out to be less steady than she thought. She was so stunned she just let it happen. She hadn’t meant to be so impossible to live with. Maybe if he’d talk to her once in a while, tell her what he was thinking. Then she might know what he didn’t like about her and could change it. Then she wouldn’t have gone so divorce-crazy and lost too much weight, or lost her job, or had to move, or had to find an apartment next to the fucking train tracks. It’s about nine-thirty, and the streets in this part of town aren’t well-lit. Annie squints into the dark parts of the sidewalk, up into alleyways—God forbid (Steph knows better than to go there, right?)—where all she can see is more darkness. Closer to downtown, the sidewalks are brighter, and there are more people on them, but none of them have Stephanie’s shiny curtain of dark hair flowing down their backs. This is pointless. It’s ridiculous. How the hell does she expect to find one girl in a city of millions? Annie knows from watching prime-time television that the police won’t even do anything unless she’s been missing for twenty-four hours. At this thought, she begins to cry. She turns on her blinker and heads home. Can’t even search properly for her own daughter.

Crab Orchard Review

u

31

Renee Evans She hates this city. She hates the way the car always bottoms out when she pulls into the parking lot. She hates the way the hallway to her building always smells like burnt pizza crust. She hates the flickering green light outside their door. She hates the way their patchy brown Berber carpet is faintly reminiscent of cat piss. She closes the door behind her and locks it, slumps onto the couch and sobs into her hands, and there is Stephanie, peeking around from in the kitchen. “Mom, you okay?” She holds a towel in her hand. She is intact. “Oh my God, Stephanie, where have you been?” Annie hugs her daughter, who feels like she didn’t expect the hug and stands there with her own arms pinned awkwardly between the two of them. “To take out the trash.” Annie squeezes even tighter and feels Stephanie’s spine pop a little. “Just the trash; I took out the trash. Mom, you’re hurting me.” “Jesus Christ, I thought you’d run away.” “Was I supposed to?” “No, goddamnit.” “All right; don’t get all pissy.” “Don’t say pissy.” “Sorry.” Stephanie holds Annie away from her and looks into her eyes. “Mom, chill out.” She walks her mother over to the well-worn couch that serves as Annie’s bed and they sit together for a moment. When Steph speaks, her voice is quiet, and it has a slight calming effect on Annie. “What would you have done if I had run away?” “I don’t know, ground you? Make you write a report about it?” “And where would you go to look up all the vocabulary words I use?” Annie returns her daughter’s smile. “Oh, ye of little faith.” Annie likes to think Steph gets her intelligence from her mother; but these moments of tenderness in her, that’s most likely Tom. “You gonna be okay?” “Yes. I’m fine. I’ll be fine. Go finish your homework.” “You don’t want to bake or something? Spend some quality time?” Annie’s smile feels more like a wince. “Not tonight. I think I’ll just take a shower and go to bed.” “Let me know if you need anything.” Stephanie looks for a long moment at her mother before she closes her door. Annie waits until she hears Vivaldi’s Four Seasons from Steph’s room before she goes to the bathroom. She locks the door behind her, turns on the shower, sits on the toilet lid, and weeps. At work, a call center where employees compete to see how many cheesy and overpriced vacation packages they can sell, Annie sits and spins her chair around in her tiny cubicle. This is the fourth job she’s had since

32

u

Crab Orchard Review

Renee Evans they moved. The carwash where she was supposed to be a car dryer was filled with dropouts who thought they knew everything and (she suspected) crack heads who couldn’t be counted on to show up for work. The pizza bar was too noisy and overcrowded. And chopping all those vegetables for the salad bar made her hands tingle at night, when she washed her one of two uniforms and never quite got the pizza smell out of them. The insurance place was a step up as far as she was concerned, but that woman and her ten o’clock boiled egg-white breaks and the way she dragged her feet around the office, flaunting those breasts that were just a little too high and tight for the mother of a twenty-something—God she was glad to be out of there. And now, even though they have to do that embarrassing cheer every morning, and Sam, her supervisor, with his too-perfect salt-and-pepper hair and too-white smile, has put little smiley-face stickers on her phone console to remind her to “smile into the sale,” at least she has her own space. She has decorated it with a string of purple Mardi-Gras beads (to let the single men know she’s spunky), a tiny bamboo plant in a clay pot (to add some life and contrasting color to this hellhole), and what Sam has referred to as her “Stephanie shrine.” The bulletin board on the wall in front of her, which is supposed to be tacked with the company’s weekly inspirational memos or sales checklists or copies of the different vacation packages, is plastered with a collage of All Things Stephanie. There are pictures, of course: of Steph’s fifth Halloween, when she was Minnie Mouse, of her laughing on the merry-go-round, her hair a dark flash, like a bird in flight behind her, standing in a float ring and watching the water on the rocky beach where she grew up (Tom has been cut out of this one), several Christmases, and her last two school pictures— the first with glasses, braces, and frizzy hair, and the second (only a year later!) with clear eyes (contacts) and straight teeth, a fresh, glossy haircut, and if she looks just hard enough, a bit of mascara and a dab of lip gloss. Just beautiful. And all of it serves as a distraction—some people pin up posters of the sorts of vistas they’re supposed to be pitching, but Annie suspects they become fantasy spots and the salespeople stop describing the white sand and bluer-than-blue water in the cove and keep those sorts of thoughts to themselves, because, really, telemarketers deserve vacations, too. She and Tom used to pack up their little pop-up camper and spend a week at a time roaming the countryside. They’d been all the way out to Maine, where they purchased lobsters for a dollar apiece right off the boats and had them boiled at a little roadside stand there. They went to the Gulf of Mexico, where Annie got stung by a jellyfish and Tom refused to pee on her because Stephanie was right there and screaming even louder than Annie. And when Annie remembers the Redwood forest, the thing she remembers the most is how surprisingly quiet it was there. She and Steph both took

Crab Orchard Review

u

33

Renee Evans vows of silence for the car ride home, but Stephanie broke hers when Tom made her giggle by singing that song about a lion in the jungle. But now Annie’s vacation is Stephanie. Always Stephanie. The next time Annie whisks the two of them away, it will be to somewhere better than Chicago, and they won’t have to worry about responsibilities, just about relaxing and having fun. When Annie’s phone rings, the sound is unfamiliar to her at first, and it takes her a second to figure out what it is. It’s her supervisor. “Annie, you planning on making phone calls today, or am I paying you to sit there and play around in your chair?” She peeks over the top of her cubicle and toward the phone on the wall where she knows Sam will be standing. He’s such a douche bag, he can’t even walk down the aisle to do his job. Can’t taint himself by mingling with the untouchables. Annie smiles into the phone and puts a positive spin on her words, just like she’s been taught—she really was paying attention, she couldn’t help it—during all those continual training seminars they have every other Friday of the month. “I was just picking up my phone to make another call when you rang, Sam. Taking some time to regroup, so I can hit it with an extra burst of energy, thanks!” Asshole. She switches the line and dials a number she knows by heart. A woman with a nasal voice Annie recognizes answers and announces the school’s name. “This is Joyce, how may I help you?” “Yes, Joyce, this is Annie Steinhauer, mother of Stephanie Steinhauer. I don’t suppose you could pull her out of class so I could talk to her for a moment, could you?” “Is it an emergency, Ms. Steinhauer?” “Well, not really.” “Then I can’t pull her out of class.” Annie can almost see her lick the tip of a pencil before she holds it to a piece of paper. “Would you like to leave a message?” “Then it’s an emergency.” “And what’s the nature of the emergency?” Joyce sounds skeptical. “I think there’s been a death in the family.” “You think?” “Yes.” There is a pause in which Joyce does something on the other end to regain her composure—there’s a whole list of things Annie’s been taught to do in a situation like this: punch the squishy back of her chair, squeeze a stress ball, bite her knuckle/tongue/pencil, roll her eyes, hold her breath and count, flip off the phone (though, Joyce seems to be a little more professionally composed than to flip off a phone in a public school), and Annie has used each and every one of them on her own job; she thinks it’s almost funny how this is a battle of in-the-phone-business people. But Joyce

34

u

Crab Orchard Review

Renee Evans comes back on, firm, but collected: “There is no family emergency, is there, Ms. Steinhauer?” Shit. “There might be.” “Listen, if you want to come down here to speak to your daughter, that’s your business. But I’m not going to pull her out of class to chit-chat.” There is another pause. “You’ve called here before, haven’t you?” Annie hangs up. It’s all right. She wasn’t planning to work any more today, anyway. She watches for Sam to appear and hover on the perimeter of the floor of cubicles as she shuts down her work station and gathers her purse. He is nowhere she can see. She makes it all the way out to the car without being spotted and thinks maybe this will be her lucky day. It’s only half-past one, and the sun’s brightness seems to be shining out from inside a jar: the edges of everything—the low brick building, the parking lot, the row of beat-up cars, her own hand in front of her holding the car keys—have softened and begun to blur into one another. This is one of those moments. There is a clarity in the way she paces one foot in front of the other. It reassures her that yes, whatever she is doing (at this point she hasn’t exactly made up her mind what that is) is right. The pace of her step, the angle of her shoulders, the way the seat belt buckle clicks definitively, how she remembers to check her mirrors and adjust the radio station before she puts the car in reverse and slowly press the accelerator: the sign of order. And if she continues at this pace, in this direction, then what? All the good she has deserved will step forward, come bubbling up to greet her, as if to say, yes, this is all for you. You are a fine woman, a fantastic mother who should be proud of her daughter. Continue doing what you have been doing, and you will be pleasantly surprised. And yes, she will go to Stephanie’s school, pull the girl from class, and take her somewhere—she’ll have to decide where later—special, where Steph will know she is loved. Maybe they could go to the salon, get matching pedicures—with the leg sugar scrub and everything—or get their hair shampooed, or go try on prom dresses, or maybe they’ll pig out on hot dogs and custard. Except Stephanie will say that’s all frivolous, and that it serves no one but themselves (again with that sense of moral superiority from Tom), and she’ll want to go to an art museum. That might not be so bad. Annie is so caught up in her reverie, she misses a turn and becomes disoriented for a moment. She is embarrassed, though she realizes there is no reason to be: no one knows it’s a mistake but her. Still, now her rhythm is off; she has to turn around, and she won’t recognize the street from the opposite angle. Plus, she’ll have to make an unexpected left turn, which always freaks her out a little. She drives the proper route without any further mishap, but she’s lost that sense of confidence. She pulls into one of the guest parking spaces at

Crab Orchard Review

u

35

Renee Evans the middle school, a low building with a new-looking façade of light brown bricks. A sign out front spells out the school’s name and cheers on their mascot, then announces the final day of school—so much later in the summer than Annie thinks it should be. She may pull Stephanie out of school earlier than that for some other undetermined family emergency. As a visitor inside the building, Annie is directed to the office, where she’ll have to sign in or out or maybe both. While she was hoping to not run into Joyce, she isn’t surprised, really, when the woman with short, dark hair and severe-looking glasses scowls up at her from behind a nameplate that reads “Joyce Francks.” “May I help you?” Joyce’s voice is even more piercing in person. Annie draws herself up in an attempt to regain her poise. “I’ve come to pick up Stephanie Steinhauer,” she says. “My daughter.” Joyce’s eyebrow twitches almost imperceptibly, but she maintains the professionalism it has probably taken her years, decades maybe, to finetune. “Do you know what class she’s in?” “Uh, no.” “I’ll have to look her up, then,” Joyce says, then turns to her computer and starts typing and clicking. “S-t-e-i-n?” “Yes. She’s in seventh grade.” Joyce nods, as if she already knew this. “Looks like she’s in Mrs. Roberts’ class. One moment, I’ll see if I can’t send her.” Joyce picks up a telephone, dials a number, then waits. “Mrs. Roberts?” A pause. “Could you please send Stephanie Steinhauer to the office? Her mother’s here to pick her up.” Another pause. Joyce seems to be listening intently. “Oh, okay. Thank you.” Joyce hangs up the phone then looks up at Annie. “Mrs. Roberts says Stephanie isn’t in her class—hasn’t been all hour.” “What?” “Was she in her classes this morning?” Annie’s fingers have begun to tingle. Her face feels cold. “I don’t know. Should be.” Joyce turns back to her computer. She types and clicks to a different screen. “Wonder if she’s been absent all day. Are you sure she came to school this morning,” Joyce looks over the rim of her glasses at Annie, “or did you go to work and leave her at home to get to school on her own?” Of course she left Stephanie at home this morning. She does that every morning, and she gets to and from school just fine. There’s never been any trouble. “No, it’s not like that,” Annie tries to explain. “It looks like she’s been absent a lot this year,” Joyce says, squinting at the screen in front of her. “Fourteen times since the beginning of the term. Daughter been sick a lot?” Joyce looks doubtfully over at Annie. “No. She’s healthy. She does her homework. She’s—she’s responsible.” But Joyce is already referring her to the school’s truancy officer. Joyce is

36

u

Crab Orchard Review