F

IRSTLY, we’re not doing horticulture for starters – more a dash of Greek myth and mystic and the story of the mythological maiden Andromeda who was chained to a rock as a peace offering to a sea monster known as the Kraken.

Legend has it that the young princess’s mother, Queen Cassiopeia, was full of vanity and boasted about her own beauty, but to cool the gods’ anger she did a dastardly deed, chaining her daughter to a rock on the beach as a sacrifice to the monster.

Enter Perseus, Greek hero and slayer of big beasts – including the hideous serpent-ridden Gorgon Medusa – who saved Andromeda from her watery grave.

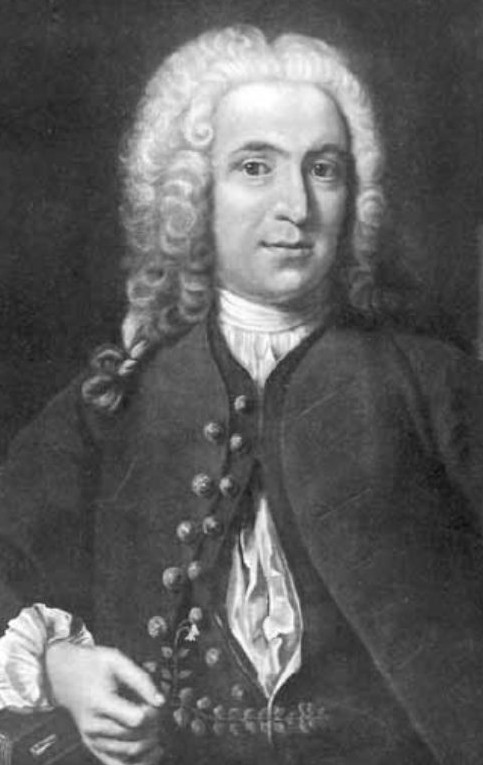

Clearly impressed by such heroics, the renowned Swedish botanist, physician, zoologist and the “father of modern plant taxonomy”, Carl Linnaeus (pictured below), named a plant after her.

And so we come to andromeda with a small “a”, a genus of just two species of low-growing, wiry-stemmed evergreen sub-shrubs which flourish in acid peat bogs around cool, temperate regions of the northern hemisphere and as far north as the Arctic.

Often referred to as Bog Rosemary, andromeda may have a posh-sounding name, yet it belongs to a quite modest plant family and bears clusters of pretty bell-shaped flowers from spring to early summer amid handsome blue-green foliage.

My own Andromeda is variety Blue Ice (pictured above) – and here’s where horticulture stretches the facts just a little with the name Blue. No, it’s far from blue or even blueish, more a distinct pink array of blooms that often practically obscure the leaves. Still, we all remember the rose Blue Moon which, at best, is a pale lilac and can’t even claim to be a purple-blue. There are plenty of other pseudo-blues.

Blue Ice is one of a handful of varieties of Andromeda polifolia which reaches about 14in high but spreads to twice that dimension. Compacta and Nikko produce similarly coloured blooms on even shorter stems while Alba is the pure white among the bunch. Whichever takes your fancy, andromeda is perfect for ground cover or a spot near a border’s edge.

A mix of sun and shade suits them best and – here’s the important bit – in soil that’s moist and slightly acidic. Other than that, they are not difficult to grow, are long-lived, will benefit from an occasional mulch of leaf-mould and will do a patio planter proud. The maiden Andromeda – if she really did exist – would surely warm to these cold-weather gems – little beauties that deserve a bigger presence in our gardens.

¶ If you cannot find andromeda at the garden centre you’ll be able to turn up several suppliers online.