Why doesn’t California have a feijoa industry like New Zealand’s?

Of all the exotic plants in Dr. Francesco Franceschi’s Santa Barbara gardens, few inspired as much excitement as the feijoa. Little more than a decade after Dr. Franceschi received his first seeds from France, the feijoa was hailed as a “wonder fruit” that would “soon be one of the most popular sugar fruits in the United States.”1 In 1914, the Santa Ana Register gushed, “Without question the Feijoa, under California methods of propagation, selection and culture, will reach a great state of perfection”.2 Advertisements claimed it was the most popular new fruit since the avocado.3 In 1915, the price of feijoa seeds skyrocketed to $6 a gram4, the equivalent of $145 today for a small seed packet. Newspapers enthusiastically reported on plantings in Santa Monica,5 Escondido,6 and Butte County7 (near Sacramento).

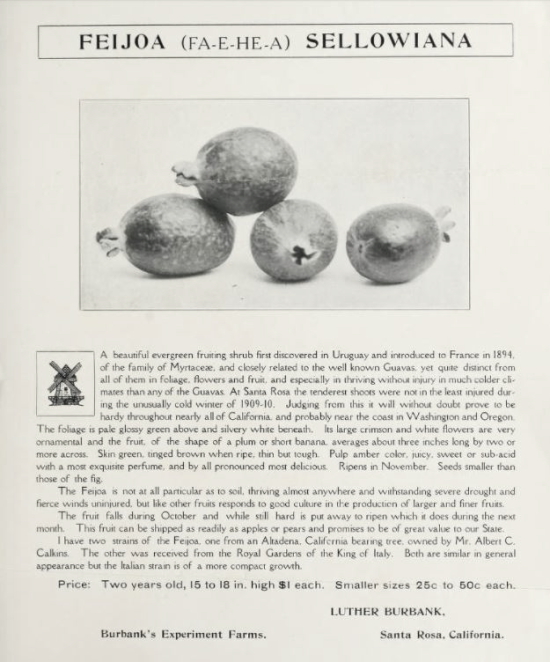

Many California nurserymen (they were all men) championed the feijoa in the early part of the century. Prominent names include Douglas William (D.W.) Coolidge of the Rare Plant Gardens in Pasadena, who introduced the “Coolidge” variety; William Boyes of Lomita, who developed the “Choiceana”; Charles Parkman (C.P.) Taft of Orange County, also known as the father of the California avocado industry; and the famous botanist Luther Burbank, who had an experimental farm in Santa Rosa, north of San Francisco. Dr. Frederick Wilson Popenoe, an expert in Latin American horticulture, wrote glowingly that “few plants can offer such an appeal to public favor.”8 The State of California predicted that the feijoa would be a “complete success”.9

But the feijoa boom soon went bust. Growers discovered that the size of the fruit varied greatly, and many trees bloomed profusely but did not fruit at all.10 In 1919, the respected nurseryman George Christian Roeding (owner of the California Nursery Company in Niles) wrote that the feijoa was “Another of our semi-tropical fruits which was boomed to the limit by over-zealous nurserymen without testing out its value fully. This fruit is simply another example of having its value extolled before determining some of the salient facts concerning it. It was widely distributed, and although it blossomed profusely the bushes failed in most instances to set fruit, and in consequence of this it lost its popularity.” Roeding did have high praise for the feijoa’s “mingling of flavors” and he predicted it would be “planted again on a limited scale.” He noted that “varieties are now being introduced that have fruit twice the size of a hen’s egg, and are known to fruit regularly and abundantly.” He thought the feijoa “should have a place in every garden.”11

In 1924, the Los Angeles Times ran a long article by Knowles Ryerson, a young horticulturalist with the state’s Agricultural Extension Service. Mr. Ryerson later became an eminent professor and eventually dean of agriculture at the University of California, Berkeley. Ryerson was not bullish about the feijoa’s commercial prospects. “Great things have been expected of the feijoa”, he wrote, but most of the plantings made in the previous decade “have been abandoned at the present time.” He identified “several reasons why commercial plantings have failed to prove very profitable.” First, “the feijoa is a new fruit, unknown to the trade and to consuming public alike. It has to compete with many other fruits.” Unfortunately, “most of the fruit offered for sale has come from seedling trees and has no uniformity in size, shape, color, flavor or quality.” The fruit itself “is not very attractive” and the “buying public is not too prone to try new things, which are not particularly attractive, especially when the price is rather high.” Mr. Ryerson predicted that the feijoa would remain “a home garden fruit” for the foreseeable future.12

Ryerson was right. By 1934, the Los Angeles Times described the feijoa as a “desirable hedge plant” that was “ideal for home planting”, with only “limited commercial possibilities”.13 Over the next five decades, the feijoa received regular attention in California newspapers, gardening books and magazines, but only as an ornamental shrub with a pleasant-tasting fruit that made a nice jelly.

People still raved about the feijoa—or not. According to a San Bernardino newspaper in 1950, “Many people do not like the [feijoa] until they have acquired a taste for it.”14 One’s opinion might depend on the local climate, which is a challenging thing about the feijoa. Feijoa trees are hardy, and they grow well in many environments where their fruit is mediocre. Gardeners in the San Francisco Bay Area discovered that feijoas tasted best on the cool and foggy coast, rather than the hot and sunny valleys.15 San Bernardino is on the edge of the Mojave desert, where delicate feijoa fruit bakes in the heat, especially if it’s a variety that ripens early.

In 1954, the Los Angeles Times reported that a Norwegian farmer named Oluf Dahlfe was growing feijoas on his Central Valley ranch in Tulare County south of Fresno. Mr. Dahlfe thought his “guavas” could become a million-dollar industry. However, when he tried to sell them to stores and hotels, he had to give them away on a sampling basis.16

Meanwhile in New Zealand, feijoas were flourishing. The earliest feijoas in New Zealand were California varieties, including the Coolidge, Choiceana, and Superba. As in California, they were mostly used as landscape plants, appreciated more for their attractive foliage and flowers than for their fruit. An Aukland nurseryman, Hayward Wright, took a liking to the feijoa and spent decades importing and selectively breeding trees for improved fruit quality, hardiness and good storage characteristics. By the 1980s, New Zealand had a profitable feijoa industry built on Hayward Wright’s cultivars such as the Mammoth and the Apollo.

The feijoa’s success in New Zealand inspired renewed interest from California fruit growers in the 1980s. At its peak, the Feijoa Growers of California had some eighty members working hard to develop a wider market for the feijoa.17, 18 Unfortunately, these efforts relied on commercial feijoas from New Zealand, rather than the improved local varieties which nurserymen like Frank Serpa and Alexander Nazemetz had quietly adapted to California’s microclimates. The New Zealand feijoas did poorly when they were planted in California’s San Joaquin Valley.19 Although feijoa trees can grow vigorously in hot, sunny weather, the fruit is highly sensitive to heat. Daytime high temperatures around Modesto often exceed 100°F (38°C) in the summer and the humidity can dip into single digits. By contrast, summer days on New Zealand’s North Island are usually in the 70’s (21-27°C) and humid. By 2011, there were only 10 small feijoa growers still active in California.20

The feijoa is still a popular fruit for backyard gardeners in California, but it seems unlikely that there will be any major effort to develop it as a commercial crop for the foreseeable future. The problems that Knowles Ryerson identified in 1924 have not been completely solved. Although California feijoas are larger and more flavorful than ever, the fruits from individual trees are still highly variable.21 Commercial growers need trees that reliably produce fruit of consistent size, appearance and quality; otherwise consumers won’t buy them. But fruit trees in their wild state have no incentive to be consistent. Fruit has only one purpose for a tree: to attract birds and animals to disperse its seeds. The tree doesn’t know what sorts of critters may be around on a given day, so it makes sense to provide a variety of choices. Also, it takes energy for the tree to grow fruit and sweeten it with sugar. Large, sugary fruit is wasteful. If smaller, blander fruit will do the job just as well, that’s good enough for the tree.

These tendencies have to be completely bred out of the tree to make it a commercial success, which takes many generations of selection. On top of that, feijoas evolved in subtropical forests where it rains almost daily. Although they’re drought tolerant, they need supplemental watering to produce good fruit in California, where we are chronically plagued by drought. Access to water is an obstacle for new growers, and existing growers are unlikely to risk their water allocation on a speculative market for feijoas, when they can make a guaranteed profit on peaches or almonds.

In the end, maybe it’s not so bad if California agribusiness ignores the feijoa. After all, this is the business that gave us supermarket bins filled with eye-catching but tasteless peaches, and plump, red tomatoes that are pink and flavorless on the inside. Fruit that ships and sells well does not necessarily taste so great. So I think I’ll happily enjoy the wild flavor and unpredictable charms of homegrown feijoas for many years to come.

(1) Prof. J.L. Stahl, “The Feijoa in California“, The Ranch (Seattle, WA), 15 Dec. 1913, pages 6-7.

(2) Reginald Brinsmead, “A Promising New Fruit for Southern California“, Santa Ana Register, 21 Apr. 1914, page 4.

(3) Armstrong Nurseries advertisement, “Plant Feijoas“, Los Angeles Times, 24 Jan. 1915, Part II, page 10.

(4) “New Fruit for This Country“, Los Angeles Times, 26 Sept. 1915, Part II, page 8.

(5) Ibid.

(6) “Feijoa Sellowianas Bloom at Escondido“, Santa Ana Register, 28 May 1914, page 1.

(7) “Rare Fruit Grown in Butte County“, San Francisco Call, 13 July 1912, page 23.

(8) F.W. Popenoe, “Feijoa Sellowiana: Its History, Culture and Varieties“, Pomona College Journal of Economic Botany, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Feb. 1912), p. 217.

(9) California State Commission of Horticulture, Monthly Bulletin, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Jan. 1916), pages 22-23.

(10) Walter Ficklin, “Information Wanted About the Feijoa“, California Cultivator, Dec. 19, 1914.

(11) George C. Roeding, Roeding’s Fruit Grower’s Guide (Fresno, Calif., 1919), page 76.

(12) Knowles Ryerson, “That Popular Fruiting Ornamental, the Feijoa“, Los Angeles Times, 6 Apr. 1924, Farm and Tractor Section.

(13) W.H. Williams, “The Feijoa’s Ideal for Home Planting“, Los Angeles Times, 11 Nov. 1934, Southland Home and Garden Section, page 7.

(14) Andrew McCornack, “Feijoa Deserves More Use as Garden Shrub“, San Bernardino County Sun, 1 Jan. 1950, Home-Garden Section.

(15) Iva Newman, “Ornamental Trees with Tasty Fruits,” The Times (San Mateo, California), 15 Mar. 1968, page 14.

(16) “Exeter Rancher Claims Guava Growing Can Become a Million Dollar Industry,” Los Angeles Times, 14 June 1954, Part III, page 7. The article refers to “guavas” but is clearly describing the feijoa because it says that the fruit drops off the tree when ripe and the grower “just makes daily tours of the trees, picking up the fallen fruit.” True guavas do not fall off the tree and are usually picked green.

(17) Stephen Ferris, “New Zealand Feijoa May Take Limelight from Kiwi Fruit“, Santa Cruz Sentinel, Nov. 4, 1987, page D1.

(18) Judith Sims, “Beyond the Kiwi: Small Farmers Cash In On California’s Appetite for Nouvelle Produce“, Los Angeles Times Magazine, July 16, 1989.

(19) Robert Chambers, “CRFG Cofounder Paul Thompson: Pioneer Rare Fruit Grower“, Fruit Gardener, March-Apr. 2008, page 21.

(20) Elhadi M. Yahia, Postharvest Biology and Technology of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits (Woodhead Pub., 2011), page 118.

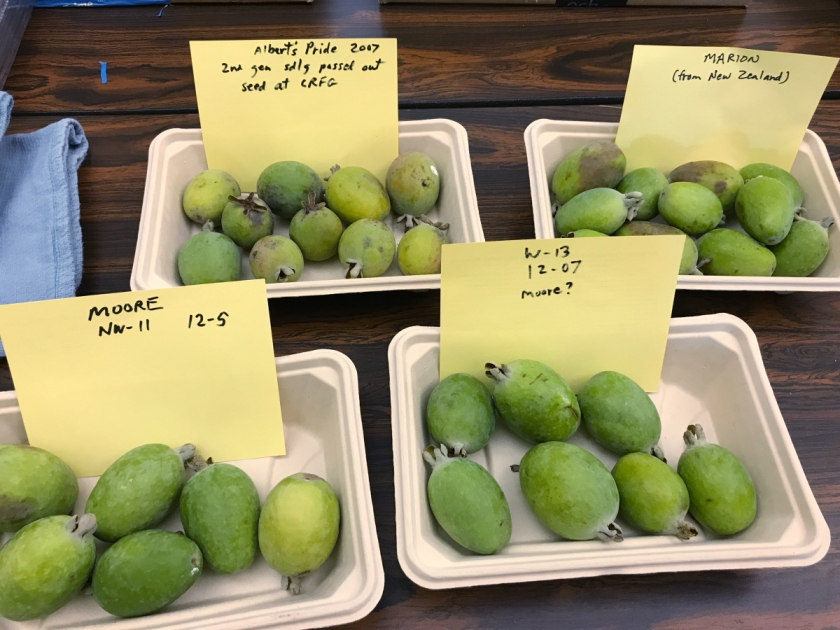

(21) Presentation by Mark Albert at a meeting of the California Rare Fruit Growers of Santa Clara County on Dec. 9, 2017.

FREMONT—Once, when Frank J. Serpa was a very young boy in the Azores, a young priest got him interested in plants and green things.

FREMONT—Once, when Frank J. Serpa was a very young boy in the Azores, a young priest got him interested in plants and green things.

The first feijoas in California were grown by

The first feijoas in California were grown by  The “Coolidge” was the most common feijoa planted in California backyards during the early 20th century. It was developed by the Coolidge Rare Plant Gardens in Pasadena. According to the

The “Coolidge” was the most common feijoa planted in California backyards during the early 20th century. It was developed by the Coolidge Rare Plant Gardens in Pasadena. According to the