by Piter Kehoma Boll

Here is a list of species described this month. It certainly does not include all described species. You can see the list of Journals used in the survey of new species here.

Bacteria

- 18 new actinobacteria: Galactobacter caseinivorans, Galactobacter valiniphilus; Actinomadura logoneensis; Actinomadura roseirufa; Marinitenerispora sediminis; Corynebacterium choanae, Corynebacterium pseudopelargi, Corynebacterium gerontici; Micromonospora radicis; Arthrobacter celericrescens; Gandjariella thermophila; Fudania jinshanensis; Nocardia yunnanensis; Agromyces tardus; Cryobacterium melibiosiphilum; Rhodococcus subtropicus; Labedella phragmitis, Labedella populi;

- 5 new bacteroids: Aquirufa antheringensis, Aquirufa nivalisilvae; Hymenobacter edaphi; Muricauda amoyensis; Mucilaginibacter terrenus;

- 1 new cyanobacterium: Sinocapsa zengkensis;

- 28 new firmicutes: Anaerobacillus isosaccharinicus; Indiicoccus explosivorum; Streptococcus hillyeri; Thermoflavimicrobium daqui; Lactobacillus yilanensis, Lactobacillus bayanensis, Lactobacillus keshanensis., Lactobacillus kedongensis, Lactobacillus baiquanensis, Lactobacillus jidongensis, Lactobacillus hulinensis, Lactobacillus mishanensis. Lactobacillus zhongbaensis; Lactobacillus pingfangensis, Lactobacillus daoliensis, Lactobacillus nangangensis, Lactobacillus daowaiensis, Lactobacillus dongliensis, Lactobacillus songbeiensis, Lactobacillus kaifaensis; Enterococcus pingfangensis, Enterococcus dongliensis, Enterococcus hulanensis, Enterococcus nangangensis; Enterococcus songbeiensis; Aquibacillus sediminis; Oceanobacillus piezotolerans, Bacillus piezotolerans;

- 31 new proteobacteria: Oceaniglobus ichthyenteri; Acidithiobacillus sulfuriphilus; Schlegelella brevitalea; Ruegeria lutea; Sphingosinithalassobacter portus; Iodobacter ciconiae; Paenimaribius caenipelagi; Colwellia ponticola; Ferruginivarius sediminum; Sphingomonas flavalba; Paracoccus nototheniae; Roseovarius amoyensis; Pseudomonas edaphica; Rhodoferax lacus; Aliishimia ponticola; Cohaesibacter intestini; Parashewanella tropica; Sphingomonas ginkgonis; Pectobacterium odoriferum, Pectobacterium brasiliense, Pectobacterium actinidiae, Pectobacterium versatile; Sulfitobacter sabulilitoris; Erythrobacter suaedae; Pseudomonas huaxiensis; Acidibrevibacterium fodinaquatile; Kosakonia quasisacchari; Poseidonibacter antarcticus; Bradyrhizobium nanningense, Bradyrhizobium guangzhouense, Bradyrhizobium zhanjiangense;

SARs

- 3 new apicomplexans: Amoebogregarina taeniopoda, Quadruspinospora mexicana; Eimeria woyliei;

- 2 new bacillariophytes: Aulacoseira lauquenensis, Aulacoseira liucoensis;

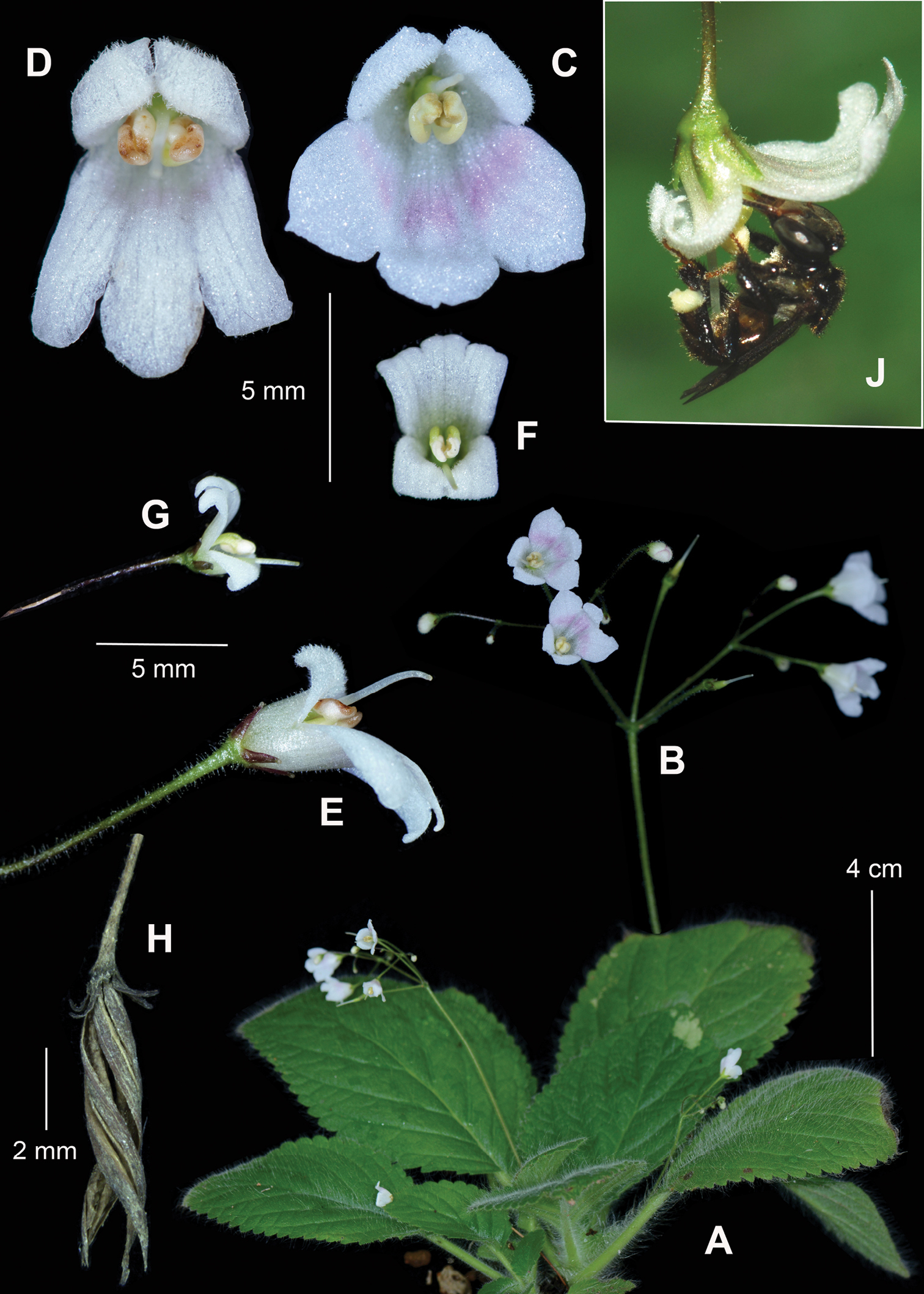

Plants

- 1 new bryophyte: Macromitrium maolanense;

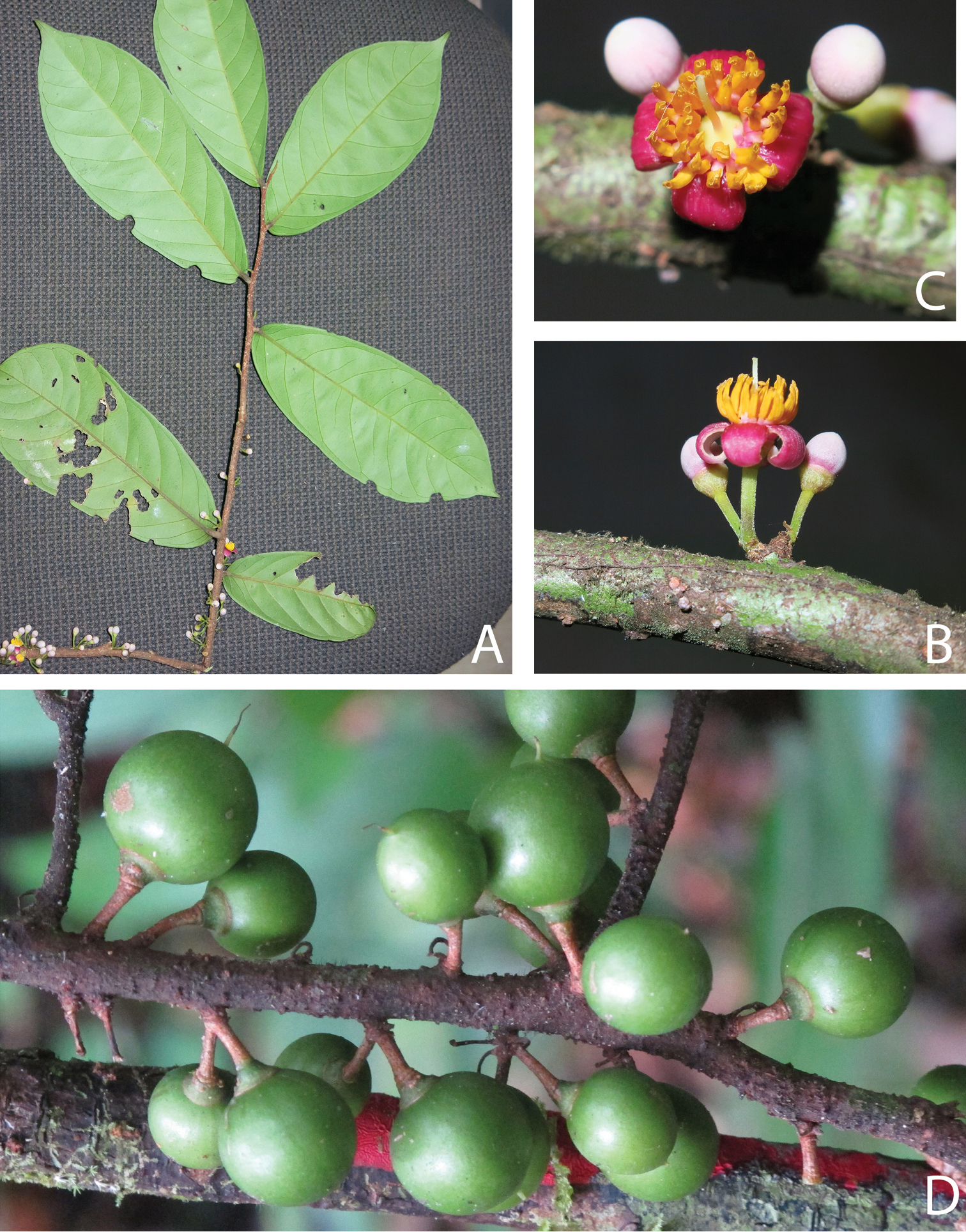

- 56 new angiosperms: Isostigma resupinatum; Muscari pamiryigidii; Petrocodon longitubus; Tagetes imbricata; Ledebouria weberi; Cremanthodium magnificum; Convolvulus hormodensis; Salvia gavilanensis; Begonia zunyiensis; Begonia saolaensis; Sphyrospermum grandiflorum; Minuartiella serpentinicola; Puccinia guassuensis; Desmodium amplistipulaceum; Crotalaria kanchiana; Lycianthes breedlovei, L. fredyclaudiae; Cornus sunhangii; Ilex montebellensis; Glandularia rupestris , G. sessilifolia; Barleria sahyadrica; Pilosocereus jamaicensis; Allium dönmezii; Zehneria tuberifera; Primulina lianchengensis; Primulina purpureokylin, P. persica, P. cerina, P. niveolanosa, P. leiyyi; Aiphanes decipiens, Aiphanes gloria, Aiphanes tatama; Coccothrinax viridescens; Hedysarum wangii; Aconitum tawangense; Stachytarpheta grandiflora; Liparis popaensis; Annona caput-medusae, A. oleifolia, Guatteria aliciae, G. attenuata, G. kamakusensis, G. pseudoferruginea, G. pseudorotundata, G. rubiginosa, G. turrialbana, Klarobelia rocioae, Tetrameranthus trichocarpus, Xylopia longicaudata; Cynometra cerebriformis, Cynometra dwyerii, C. tumbesiana, C. steyermarkii; Lachemilla rothmaleriana, Lachemilla argentea, Lachemilla cyanea; Tashiroea villosa; Rhaptopetalum rabiense; Clematis guniuensis; Pseuderanthemum melanesicum;

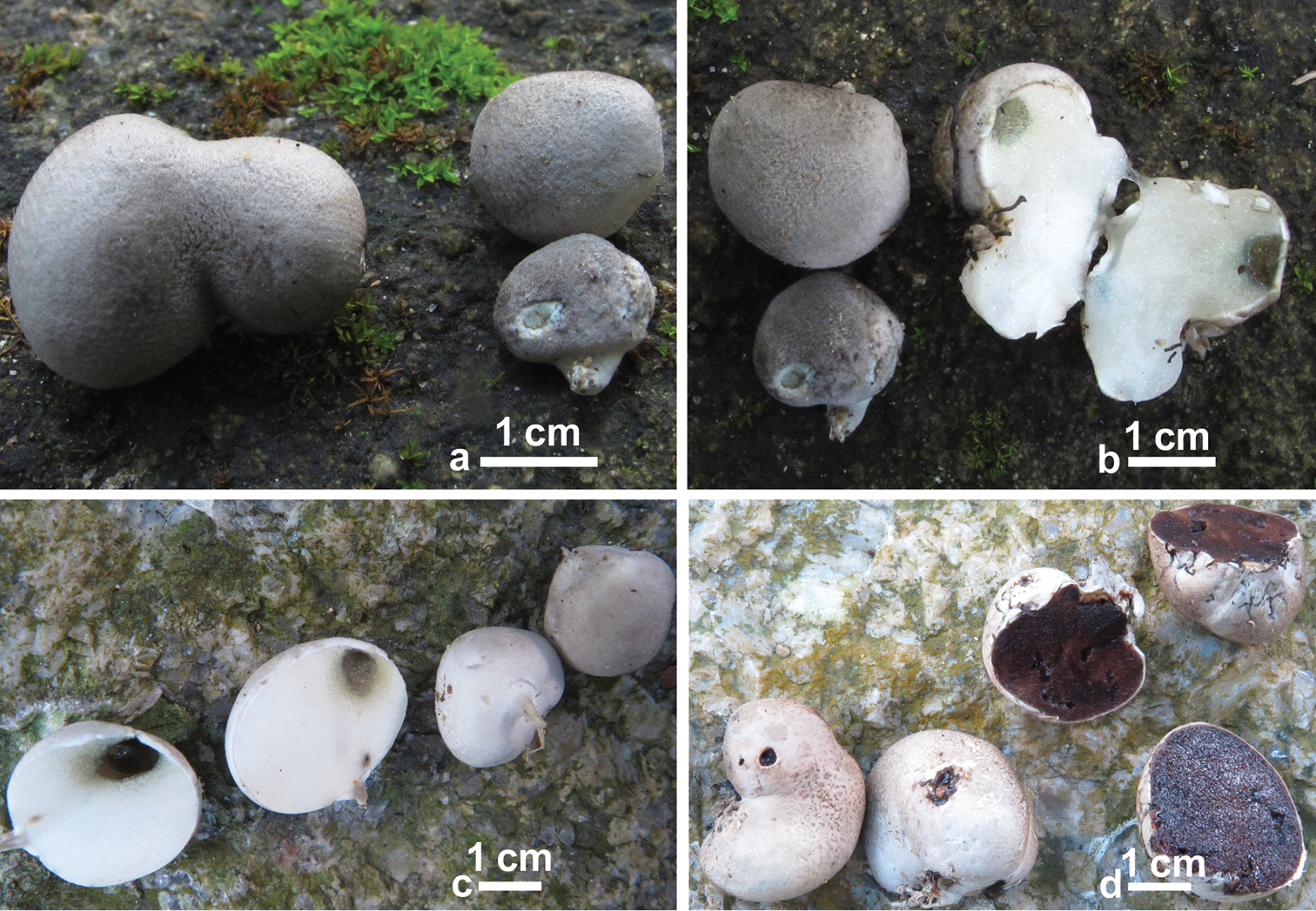

Fungi

- 40 new ascomycetes: Savoryella sarushimana; Cryptothecia panchganiensis; Asterina cerradensis, Asterina malvacearum, Lembosia matogrossensis, L. miconiphylla; Micarea fennica; Sphaeropezia leucocheila; Akanthomyces araneicola; Cladosporium passiflorae, C. passifloricola; Wicklowia submersa; Pachyphlodes cinnabarina, P. wulushanensis; Stemphylium dianthi; Ophiosphaerella taiwanica; Conioscypha tenebrosa; Dicephalospora albolutea, D. shennongjiana, D. yunnanica; Rugonectria microconidia and Thelonectria guangdongensis; Conlarium baiseense, C. nanningense, C. sacchari; Neothyronectria citri; Coryneum ilicis, C.songshanense; Ophiocordyceps asiatica, O. brunneirubra, O.khokpasiensis, O. mosingtoensis, O. pseudocommunis, O. pseudorhizoidea, O. termiticola; Micarea aeruginoprasina, M. azorica, M. isidioprasina, M. microsorediata, M. nigra, M. pauli; Aspergillus olivimuriae; Aspergillus takadae; Metschnikowia baotianmanensis; Phalangispora sinensis; Wickerhamiella shivajii;

- 13 new basidiomycetes: Laetiporus lobatus; Volvariella niveosulcata, V. guttulosa, V. ptilotricha, V. pulla; Stropharia atroferruginea; Tubaria squamata; Amanita mansehraensis; Amanita ahmadii; Leccinellum alborufescens, L. fujianense; Hygrophorus alboflavescens, Hygrophorus scabrellus; Heterocephalacria mucosa; Spencerozyma acididurans;

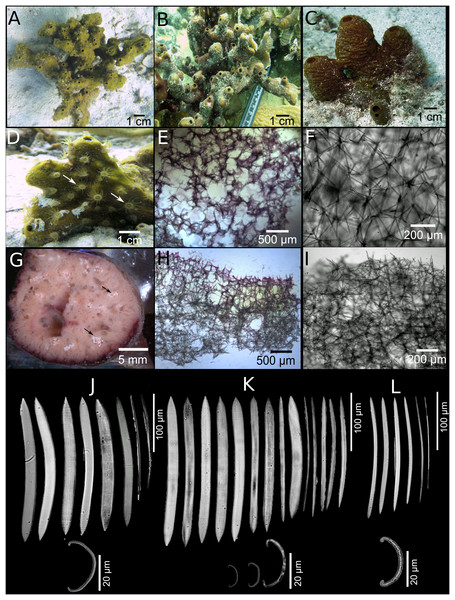

Poriferans

- 9 new demosponges: Penares mollis, P. aureus, P. vermiculatus, P. kermadecensis, P. turmericolor, P. deformis, P. okokewae, P. orbis, P. astronavis;

Rotiferans

- 6 new acanthocephalans: Plagiorhynchus (Plagiorhynchus) aznari; Acanthogyrus (Acanthosentis) fusiformis; Pachysentis lauroi; Rhadinorhynchus circumspinus, Rhadinorhynchus pacificus, Rhadinorhynchus multispinosus;

Flatworms

- 1 new polyclad: Prosthiostomum torquatum;

- 15 new rhabdocoels: Cheliplana gibarenha, C. santiaguera, C. spuriaseminalis, C. subproximalis, C. verrucosa, Carcharodorhynchus smilodon, C. papillaris, Carcharodorhynchus spiniformis, C. nativus, Schizochilus favus, S. bueycabonensis, S. atlanticus, S. espinosai, S. banesensis, S. maximus;

- 3 new monogeneans: Lamellodiscus occiduus, Lamellodiscus vesperus; Neoheterocotyle quadrispinata;

- 3 new trematodes: Atamatam amazonensis, Paratamatam sp.; Metadelphis tkachi;

- 1 new cestode: Dieffluvium nidulorum;

Annelids

- 17 new polychaetes: Aphelochaeta abyssalis, A. clarionensis, A. clippertonensis, A. spargosis, A. tanyperistomia, A. wilsoni, Caulleriella bathytata, Chaetozone akaina, C. grasslei, C. truebloodi, Tharyx hessleri; Fauveliopsis levensteinae, F. magalhaesi, Laubieriopsis blakei, Riseriopsis santosae; Amphiglena seaverae, Amphiglena joyceae;

- 1 new clitellate: Branchellion spindolaorum;

Mollusks

- 3 new gastropods: Sinochloritis lii, Bradybaena linjun; Chamalycaeus rarus;

Kinorhynchs

- 4 new species: Cristaphyes retractilis, Fujuriphyes dalii, Echinoderes brevipes, Echinoderes parahorni;

Nematodes

- 10 new species: Ascarophis morronei; Pterygodermatites (Pterygodermatites) atlanticaensis; Acanthostrongylus secundus; Malenchus gilanensis; Sabatieria chukchensis, Sabatieria parvamphis, Sabatieria major, Sabatieria multisupplementia; Physaloptera amazonica; Gyrinicola dehradunensis;

Tardigrades

- 2 new species: Meplitumen aluna; Hansenarctus toyoshiomaruae;

Arachnids

- 3 new mites: Ololaelaps elongatus; Knopkirie flascus, Kuzinellus rarotonga;

- 1 new scorpion: Centruroides romeroi;

- 9 new pseudoscorpions: Garypus latens, G. malgaryungu, G. necopinus, G. postlei, G. ranalliorum, G. weipa, G. dissitus, G. reong, G. yeni;

- 23 new spiders: Actinopus coboi, A. fernandezi, A. simoi, A. uruguayense; Macrophyes pacoti; Anicius chiapanecus, Anicius cielito, Anicius faunus, Anicius grisae, Anicius maddisoni; Herbiphantes acutalis, Labullinyphia furcata; Epiceraticelus mandyae; Cryptachaea pilar; Drassodes mylonasi , Echemus kaltsasi, Minosiella apolakia, Phaeocedus vankeeri, Turkozelotes attavirus; Draconarius baibaensis, Draconarius budanlaensis, Draconarius yigongensis, Draconarius yingbinensis;

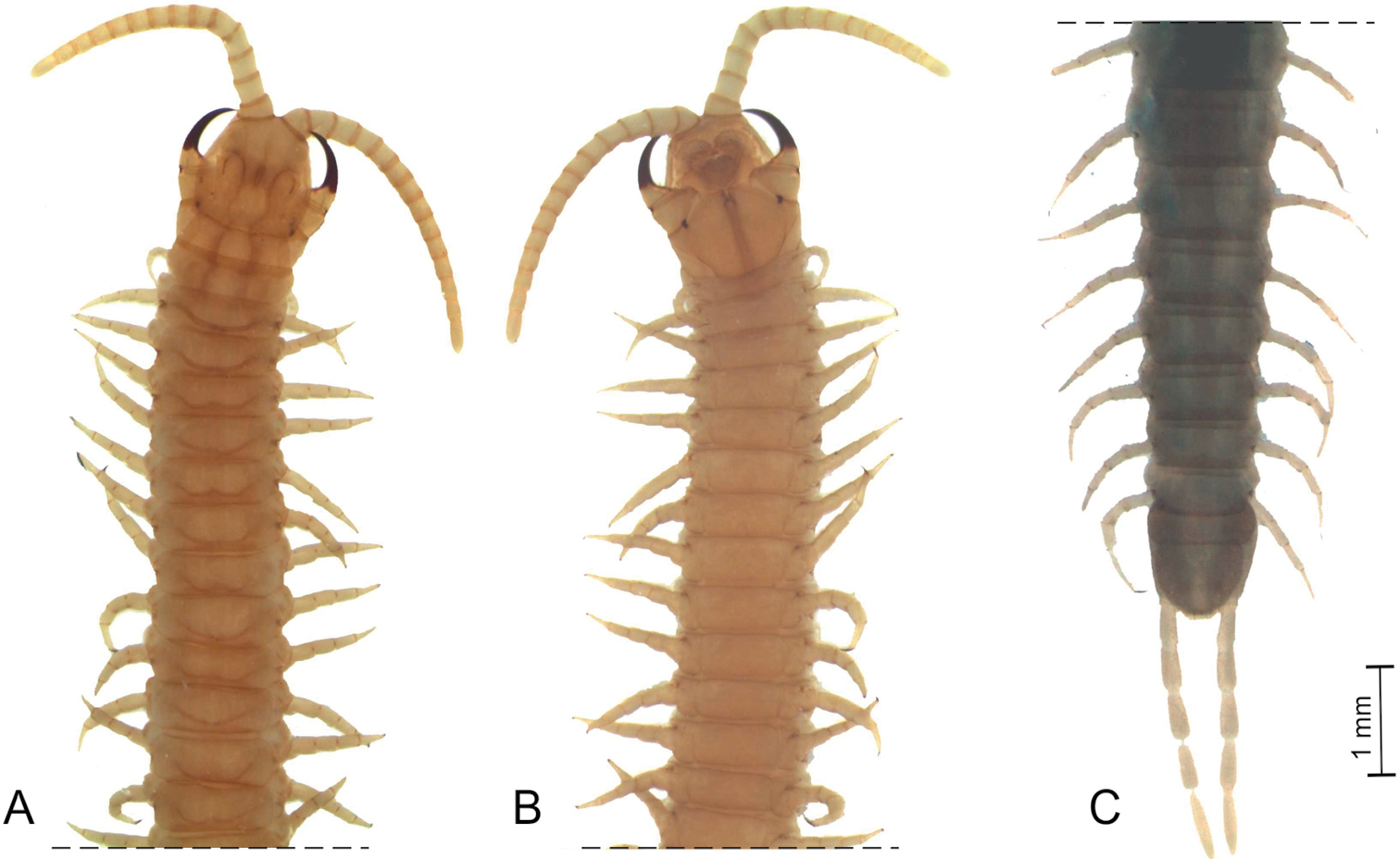

Myriapods

- 6 new diplopods: Hyleoglomeris rukouqu, Hyleoglomeris xuxiakei, Hylomus yuani, Eutrichodesmus jianjia, Trichopeltis liangfengdong, Glyphiulus maocun;

Crustaceans

- 1 new ostracod: Chelonocytherois omutai;

- 4 new copepods: Monsmeteoris wiesheuorum, M. reductus, Cylindropsyllus valentini, C. flexibilis;

- 9 new amphipods: Propejanice lagamarensis; Colomastix iemanja, Colomastix tubulosa, Colomastix marielle; Gazia gazi, Talorchestia anakao; Aciconula tinggiensis; Sarothrogammarus yiiruae; Hyalella puna;

- 1 new isopod: Caecidotea camaxtli;

- 1 new tanaid: Xenosinelobus balanocolus; Hexapleomera sasuke;

- 7 new decapods: Nennalpheus gabonensis; Synalpheus amintae; Spongicola liosomatus; Xiphocaridinella sp.; Geosesarma mirum; Barathricola thermophilus; Macrobrachium laevis;

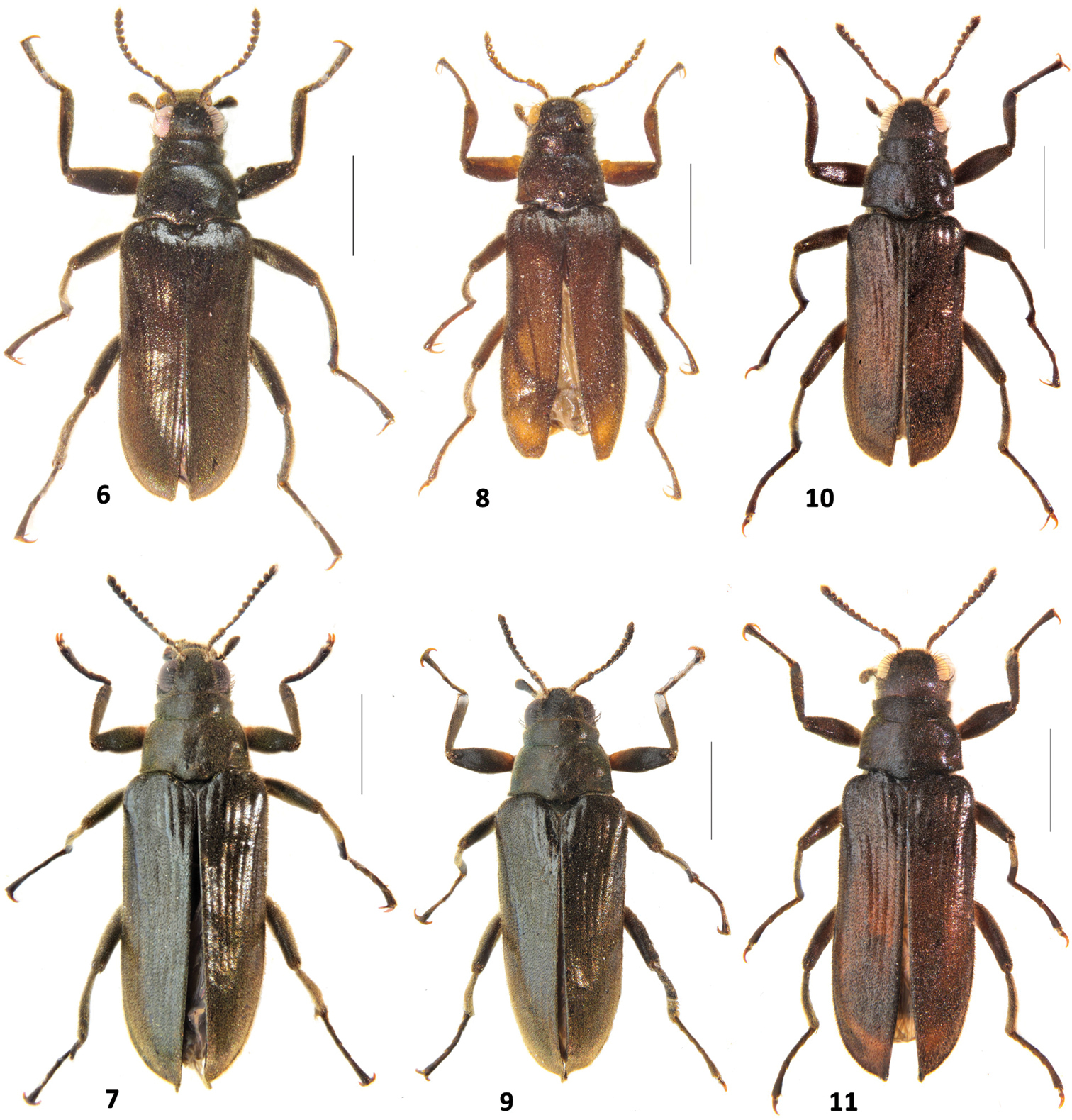

Hexapods

- 2 new collembolans: Aethiopella ricardoi; Megalothorax dobsinensis;

- 2 new ephemeropteran: Thraulus thiagarajani; Potamocloeon edentatum;

- 1 new dictyopteran: Brachylatindia xui;

- 6 new orthopterans: Phyllotrella hainanensis, P. transversa, P. fumingi; Criotettix longispinus, Criotettix undatifemurus; Indigryllus kudremu;

- 3 new plecopterans: Cerconychia trilobata; Capnia s.l. bilobata; Perlesta sublobata;

- 1 new thysanopteran: Heliothrips longisensibilis;

- 23 new hemipterans: Orius hibiscus; Stictotettix cleyerae, S. morishimai; Limnocoris chaetocarinatus, L. major, L. nanus, L. zacki; Physatocheila nigrintegerrima; Myittana (Benglebra) biflaka, M. (Benglebra) curvata; Maiestas borealis, M. maritima, M. peninsularis; Phytocoris (Compsocerocoris) amardus, Phytocoris (Compsocerocoris) hyrcaniaensis; Megacanthaspis guiyangensis; Ceratogergithus brachyspinus, Neohemisphaerius clavatus; Malaxa hamuliferum, M. tricuspis; Bambusana longispina; Esakia borneensis, E. mazzoldii;

- 87 new coleopterans: Vitacinis luziae, Nealcidion antonkozlovi, Onalcidion antonkozlovi, Leptocometes antonkozlovi; Derisemias tsutsumiuchii, Derisemias kojimai; Agrilus acacivorus, A. albizivorus, A. coco, A. monadikos, A. occultus; Sathytes borneoensis, S. liuyei, S. larifuga, S. shihongliangi; Tropanisopodus antonkozlovi, Paranisopodus antonkozlovi; Notomicrus meizon. N. teramnus; Cephennomicrus yunnanicus, C. andreasi; Scybalocanthon acrianus, S. adisi, S. arnaudi, S. chamorroi, S. federicoescobari, S. haroldi, S. martinezi, S. papaxibe; Xalpirta mauryi; Sichuanortia zhouchaoi; Barypalpus chinensis, B. holzschuhi, B. shibatai; Cionus armeniacus, C. boroveci, C. colonnellii, C. dodeki , C. harani, C. himalayensis, C. khorasanicus, C. laibalei, C. maurus, C. negevicola, C. neglectus, C. osmanlis, C. rossicus, C. rufescens, C. winkelmanni, C. yunnanensis; Yara oyaguei; Agelosus auricomus, Apecholinus imitator, Apecholinus canifer; Zeugophora cupka; Oxytrechus chioriae, O. cayambeensis; Tmesiphorus kinomurai, T. okinawensis; Rosalba contracta, R. venusta, R. skelleyi, Tethystola alboangulata, Blabicentrus similis, Pygmaeopsis apicalis, Pseudestola maculata; Esemephe peba; Hyalonthophagus pulcher; Peripus brunkei, P. didontus, P. madrededios, P. monodontus; Linan qiniangmontis; Isacanthon mariaelinae; Pharetis thayerae, Spherita newtoni; Canthon (P.) arriagadai, Canthon (P.) bonaerensis, Canthon (P.) vidaurrei, Canthon (P.) ziggy; Cymatodera acuminata, Cymatodera unica, Cymatodera parva, Cymatodera magdalena;

- 11 new neuropterans: Afroptera acuta, A. alba, A. brinkmani, A. balli, A. cylindrata , A. folia, A. koranna, A. maraisi, Nemopterella kabas, N.cedrus; Nothochrysa ehrenbergi;

- 110 new hymenopterans: Dicranorhina dinesani, D. georgei, D. sreeramani; Orthostigma (Patrisaspilota) enduwaense; Brachygaster gussakovskiji; Passaloecus bisulcatus, P. profundesulcatus, P. tuberangustus, P. tuberculiformis; Anteon ambrense, Anteon beankanum, Anteon elongatum, Anteon hoekense, Anteon mabibiense, Anteon majunganum, Anteon malagasy, Anteon musmani, Anteon nigropictum, Anteon nimbense, Anteon pseudohova, Anteon sakalavense, Anteon tulearense, Aphelopus sequeirai, Apoaphelopus fisheri, Apoaphelopus wallacei, Bocchus forestalis, Bocchus granulatus, Bocchus harinhalai, Bocchus nigroflavus, Bocchus parkeri, Bocchus ruvidus, Conganteon hawleyi, Conganteon sensitivum, Crovettia afra, Deinodryinus ambrensis, Deinodryinus granulatus, Deinodryinus nigropictus, Deinodryinus piceus, Dryinus bellicosus, Dryinus dentatiforceps, Dryinus erenianus, Dryinus milleri, Dryinus mobotensis, Dryinus nigrithorax, Dryinus teres, Dryinus tulearensis, Dryinus whittleorum, Gonatopus avontuurensis, Gonatopus bellicosus, Gonatopus comorensis, Gonatopus costalis, Gonatopus flavotestaceus, Gonatopus gumovskyi, Gonatopus hantamensis, Gonatopus harinhalai, Gonatopus karooensis, Gonatopus koebergensis, Gonatopus marojejyanus, Gonatopus minutus, Gonatopus nigropictus, Gonatopus ranomafanensis, Gonatopus robertsoni, Gonatopus rugithorax, Gonatopus scholtzi, Gonatopus wikstrandae, Lonchodryinus madagascolus, Madecadryinus ranomafanensis, Neodryinus bimaculatus, Neodryinus keleboensis; Acrogymnidia catalina, Ptenos amazonicus, Heteroperreyia andina, Derecyrta risaraldensis; Xorides nigrithorax, X. rufofacialis, X. simoni; Eniacomorpha hermetiae; Ecclitura shawi, Marshiella tupi, Streblocera brasiliana; Liphanthus jenamro, L. sapos, L. domeykoi, L. discolor, L. centralis, L. molavi, L. abotorabi, L. cochabambensis, L. fritzi, L. amblayensis, L. ancashensis, L. tregualemensis, L. yrigoyeni, L. sparsipunctus, L. aliavenus; Trachusa (Paraanthidium) pingdaensis, T. (P.) staabi, T. (P.) wuae; Telostholus celebes, T. rinjani, T. sulawesi; Acmaeodera (Acmaeodera) strumiai, A. (Acmaeotethya) dhofarica; Alexeter beijingensis; Microplitis bomiensis, M. paizhensis; Hoplocryptus qingdaoensis; Ponera tudigong; Brachymyrmex bahamensis, Brachymyrmex bicolor, Brachymyrmex iridescens, and Brachymyrmex sosai;

- 50 new dipterans: Drapetis abrollensis; Pieza ankh, P. aurislepus, P. bittencourti, P. parakake, P. parnasecon, P. rafaeli, P. silvanae, P. yeatesi; Pseudacteon trapeziformis; Medinodexia japonica; Ormiophasia guimaraesi, Ormiophasia seguyi, Ormiophasia crassivena, Ormiophasia manguinhos, Ormiophasia tavaresi, Ormiophasia chapulini, Ormiophasia buoculus, Ormiophasia townsendi; Anabarhynchus aurantilateralis, A. halmaturinus, A. venabrunneis; Ammophilomima amamiensis, A. rikioi; Riethia azeylandica, Riethia hamodivisa, Riethia paluma, Riethia phengari, Riethia queenslandensis, Riethia donedwardi, Riethia noongar, Riethia wazeylandica, Riethia kakadu, Riethia neocaledonica; Psectrosciara ahuatla, Psectrosciara otumba; Ptychoptera emeica ,P. circinans P. lucida, P. separata; Domodon caxiuana, D. inaculeatus, D. sensibilis; Eumerus grallator, E. tenuitarsis; Neuratelia altoandina, N. colombiana; Neophyllomyza clavipalpis, N. motuoensis, N. obtusa; Pseudasphondylia tominagai;

- 1 new trichopteran: Hydroptila nago;

- 33 new lepidopterans: Bucculatrix yingjingensis, B. liubaensis; Diduga bayartogtokhi, D. nigridentata, D. quinquicornuta, D. hanoiensis; Pleurota variocolor, P. azrouensis, P. ternaria; Zographetus rienki; Astrotischeria ochrimaculosa, A. colombiana; Phlogophora butvili; Sarbanissa pseudassimilis; Synanthedon auritinctaoidis, Paranthrenella helvola; Sabulopteryx botanica; Herpetogramma biconvexa, H. longispina, H. brachyacantha; Neosphecia cecidogena; Thraumata peruviensia; Zaphanta acuta, Z. anas, Z. bahiana, Z. beckeri, Z. elephanta, Z. elephanticula, Z. machaera, Z. rawlinsi, Z. stiletto; Antispila longcangensis, A. emeishanensis;

Actinopterygians

- 1 new anabantiform: Aenigmachanna mahabali;

- 1 new cypriniform: Paraschistura kermanensis;

- 2 new siluriforms: Parotocinclus pentakelis; Mystus prabini;

- 1 new perciform: Scolopsis lacrima;

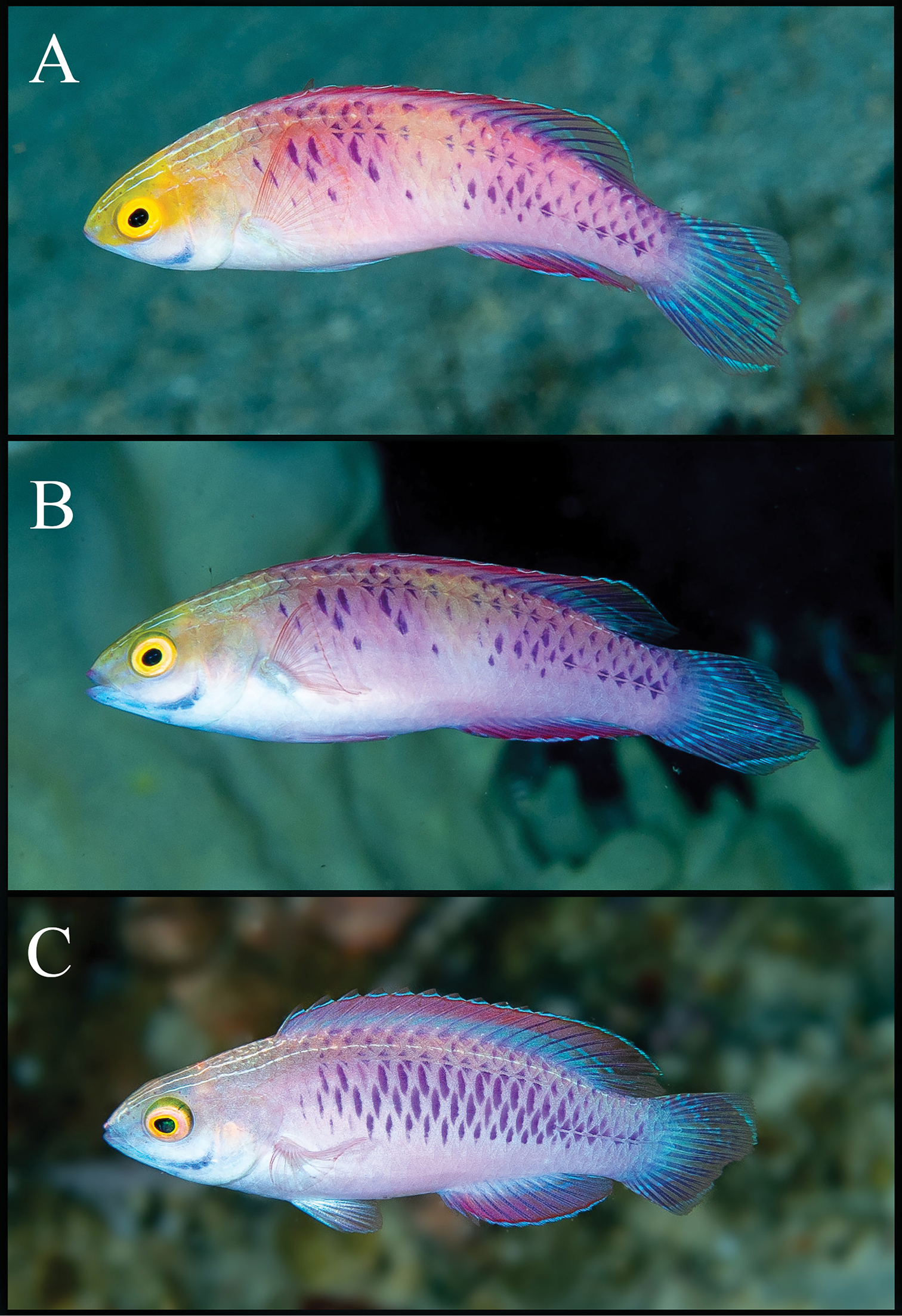

- 1 new labriform: Cirrhilabrus wakanda;

- 1 new cyprinodontiform: Leptopanchax sanguineus;

- 2 new characiforms: Hemigrammus amacayacu; Knodus nuptialis;

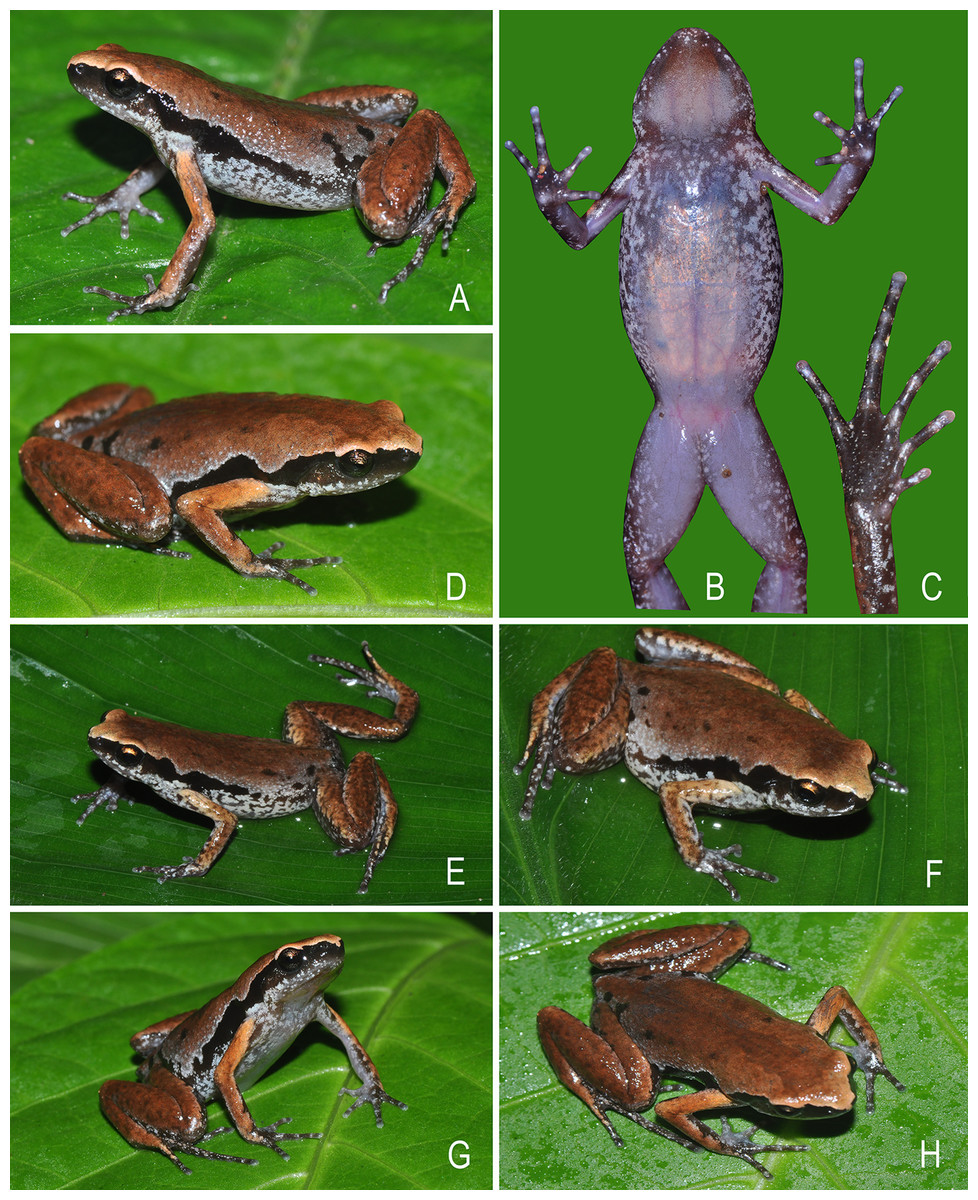

Amphibians

- 9 new anurans: Microhyla fanjingshanensis; Dendrophryniscus davori, D. haddadi, D. izecksohni, D. jureia; Allobates sp.; Paratelmatobius sp.; Pristimantis ferwerdai; Nidirana yaoica; Nidirana leishanensis;

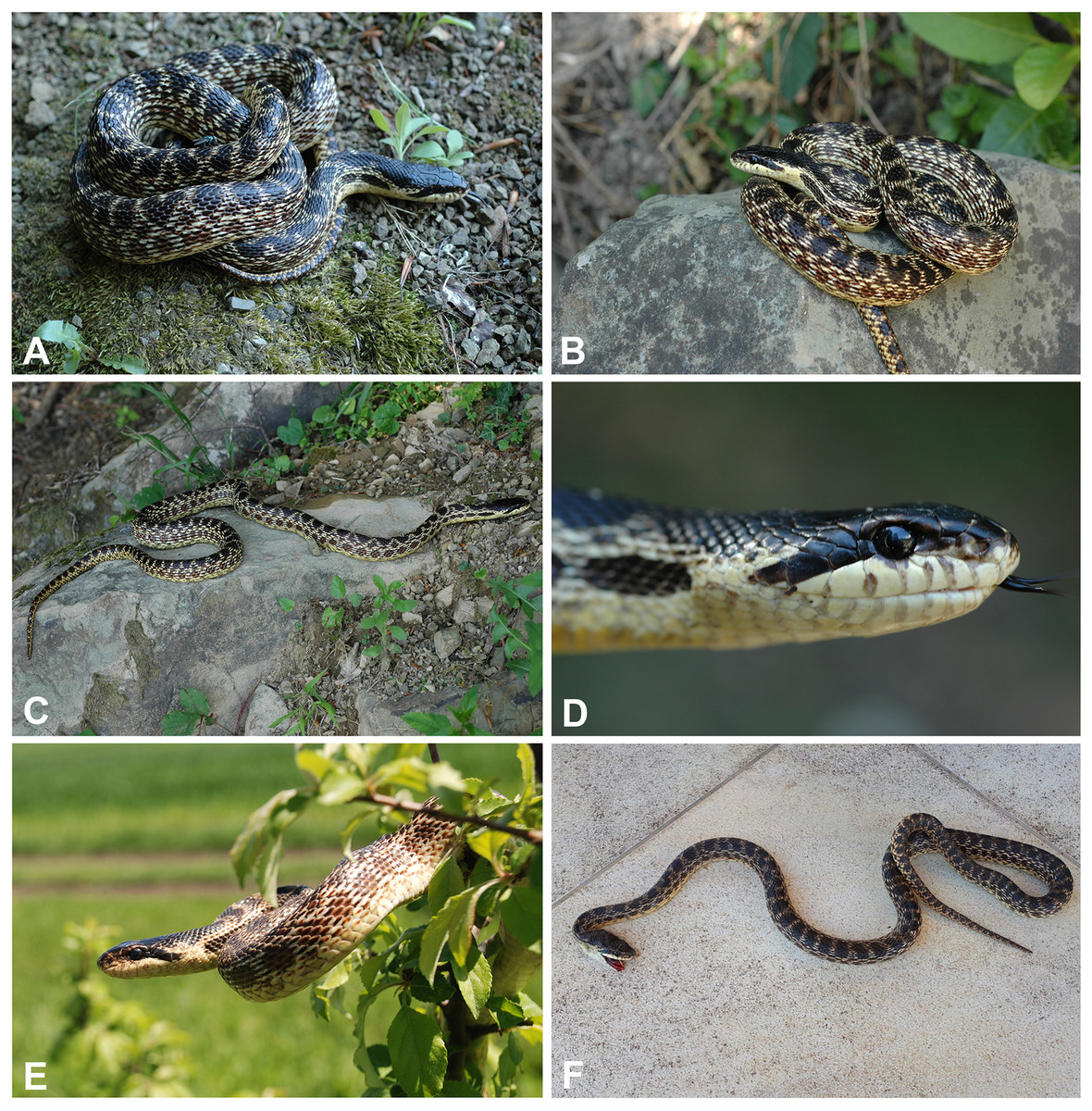

Reptiles

- 15 new squamates: Cyrtodactylus pinlaungensis; Glaucomastix itabaianensis; Ptychozoon cicakterbang, P. kabkaebin, P. tokehos; Calotes zolaiking; Hemidactylus varadgirii; Asthenodipsas jamilinaisi, A. stuebingi; Dipsadoboa montisilva; Scincella badenensis; Microgecko varaviensis; Cnemaspis tarutaoensis, Cnemaspis adangrawi; Proahaetulla antiqua;

Mammals

- 1 new primate: Mico mundukuru;

– – –

* This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.