BRASÍLIA 50 ANOS | The Buildings :: The Brasília Palace Hotel as Seen by Elizabeth Bishop in August 1958

Photo > Joseph Breitenbach

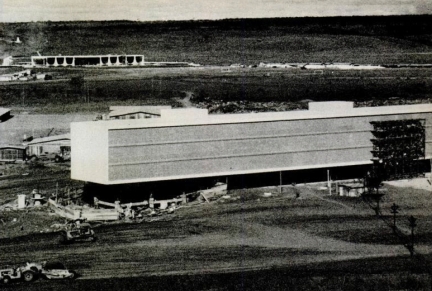

The Brasília Palace Hotel was the second of Oscar Niemeyer’s buildings in Brasília, completed in 1958 after he’d wrapped up his design work on the Palace of the Dawn (Palácio da Alvorada):

It made sense: President Juscelino Kubitschek loved showing his creation off whilst it was under construction and he needed someplace swank to house his many guests. They couldn’t all crash at his new Palace.

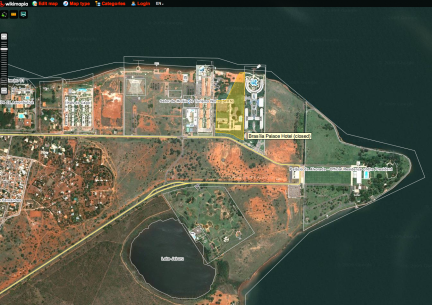

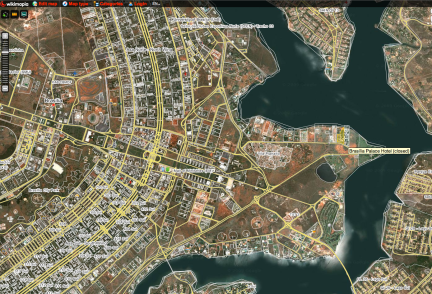

Since these were the first two edifices in the new capital, they are not aligned with Lúcio Costa’s plan piloto; they’re both off-kilter, relating to the artificial Lago do Paranoá, not the “avion” imprint of the city’s intriguing road system:

°

°

°

I always dreamed I’d stay in this particular hotel. Niemeyer’s late-50s nod to Brazilian elegance.

But when I eventually made my pilgrimage to this City of the Future, it had already been years since a fire destroyed the Palace.

It lay abandoned and forlorn for a long while. When we drove buy it in 2005 it looked really sad, just like this amazing photo from that dilapidated era:

Photo > “Brasília Palace Hotel, Oscar Niemeyer, Brasília, Brazil, 1998” by toddeberle.com

°

°

°

Well, like the proverbial phoenix, the hotel has been completely redone and is once again open for your business (see colour photos of the lobby, below).

Back in 1958, the Palace was the only place to stay.

°

°

°

Aldous Huxley and his second wife Laura were in Brazil in August 1958.

The Ministry of Foreign Relations asked him to visit Brasília and write his impressions. The Huxleys, in turn, asked their friend, Pulitzer Prize winning poet Elizabeth Bishop, to accompany them.

She wrote a never-published piece, “A New Capital, Aldous Huxley, and Some Indians,” that The Yale Review finally published in 2006. Her essay is a wonderful primary source about how the Palace appeared when it opened.

Below are some period photos of how the hotel would have looked to her when she arrived by taxi from Brasília’s small airport in August 1958:

A friend of mine, a Rio interior decorator who had just finished doing up the new hotel, had made reservations for me by two-way radio. The Brasília Palace Hotel is in one block, a hundred and thirty-five rooms, one room thick and three stories high; only a small central section rests on the ground, the rest of the building on either side being supported by concrete pillars covered with black-anodized aluminum. At night these pillars almost disappear and the hotel appears to float like a luxury-liner, an effect that seems to be dear to Niemeyer’s heart these days.

The entrance, reminding me vaguely of a New York subway entrance, is down a flight of steps into a sunken lobby; over it, at ground level, is a large, pleasant lounge, full of Saarinen chairs and marble-topped coffee-tables.

The three floors of rooms face east to the Palace of the Dawn; three corridors run the full length of the west side of the building. There is one public staircase, about four feet wide, and two small elevators (one was not working when we were there), each holding at the most six people, so that there will certainly be serious traffic problems when the hotel is filled with its quota of three hundred guests. The entire west wall is made of large blocks of cement, five inches or so thick, and regularly set into each block are rows of little round glasses – real drinking glasses, the bell boys like to inform one – their circle- ridged bottoms sealing the wall on the outside. They let in the light in thousands of spots on the walls and gray carpeting of the corridors, an effect that is extremely pretty but unfortunately, from the moment the sun starts down the western sky until early next morning, fiendishly hot. Also, I wondered how could the insides of all those little glasses ever be cleaned? Already the more casual type of guest had begun to leave cigarette butts and other odds and ends in those within reach. Between each floor a row of blocks has been left without the glasses; the holes open into an airspace above the halls, where small screened openings alternate with light fixtures along the ceilings. This is supposed to provide ventilation, but not a breath of air came from the vents, and at night, when I walked the corridor to my room at the very end, before reaching its white Formica doorway I would be dizzy from the heat. The bathroom ceilings are pierced with holes into this common airspace, too, with the unhappy result that one clearly hears the man next door taking his bath, limb by limb. The rooms, however, are large and cool, and except for the dressing-tables, well furnished. In the dressing-table mirrors a woman of barely average height (myself) sees only her chin.

Between the hotel block and the dining-room wing is a small space about as big as a tennis court and here grass had been planted and was being watered. Otherwise, in front and in back of the hotel, and for the half-mile tract between it and the Presidential Palace, the red dust blew unchecked. (A week or so after this, when President Gronchi of Italy visited Brasília, a thin layer of cement was poured over the area in front of the Palace.) Dust seeped into the hotel, tingeing the carpets and one’s clothing and the gray marble floor of the lounge was powdered with it. I watched a workman trying to clean this floor with an electric polishing machine. After producing a few big spirals edged with banks of red dust, he gave up the attempt.

This particular floor comes to an end in a free-form curve four feet higher than the floor of the dining-room, into which the lounge opens. Plants and cacti hide coyly beneath the overhang, invisible from the lounge. The one occasion on our trip when I saw Aldous Huxley openly irritated was when, just after he arrived the next day, he started walking down the lounge, against the light, and almost fell over this drop. He showed distinct signs of anger, for him, and remarked that the handrail had been in use for some thousands of years and it seemed ‘a shame to abandon such a useful invention.’

In front of the dining-room is the biggest swimming-pool I have ever seen: oval, lined with blue tiles, as yet waterless. The Presidential pool, at the far side of the Palace, is bigger than the standard Olympic pool, and this is a much bigger one than that. Permanent quarters for the hotel employees have not yet been built. Beyond the pool is a wooden paling, and inside it a collection of wooden shacks. Maids, bell boys, and chefs in their white hats, skirt the blue tile abyss and vanish into this shabby compound, and the dining-room looks out on it.

Concealed behind a curving black wall on the dining-room level are a bar and cocktail lounge, and also there was the source of some annoyance to the Huxley party – a loud, Brasilian equivalent of Muzak, which was turned on for two hours at lunch and dinner. The food was not bad, considering that all supplies have to be brought by truck or by plane from at least as far away as Annapolis; there were almost no vegetables, but always airlifted pineapples or papayas to provide us with vitamins, as well as the mushy Delicious apple, as ubiquitous here as in the United States.

That Friday night two far-off couples and I dined all alone in the big dining-room, the canned music struck up with the canned consommé, and the extra waiters looked on. After dinner two younger couples appeared in the lounge, with a baby in a basket and another small child to each couple. One mother in plaid slacks ran races with her little boy; the other joggled her baby’s basket with her foot and read a detective story.

– Elizabeth Bishop, “A New Capital, Aldous Huxley, and Some Indians.” The Yale Review, 94:3 pp. 76-114.

Azulejo Brasília Palace Hotel, Brasília “Positivo” + “Negativo”

Fundação Athos Bulcão

designKULTUR: BRASÍLIA | THE BUILDINGS :: THE PALACE OF THE DAWN AS SEEN by ELIZABETH BISHOP in AUGUST 1958

About this entry

You’re currently reading “BRASÍLIA 50 ANOS | The Buildings :: The Brasília Palace Hotel as Seen by Elizabeth Bishop in August 1958,” an entry on designKULTUR

- Published:

- 2010/06/29 / 19:05

No comments yet

Jump to comment form | comment rss [?] | trackback uri [?]