ArtSeen

Mark Rothko: Paintings on Paper

On View

National Gallery Of ArtMark Rothko: Paintings on Paper

November 19, 2023–March 31, 2024

Washington, DC

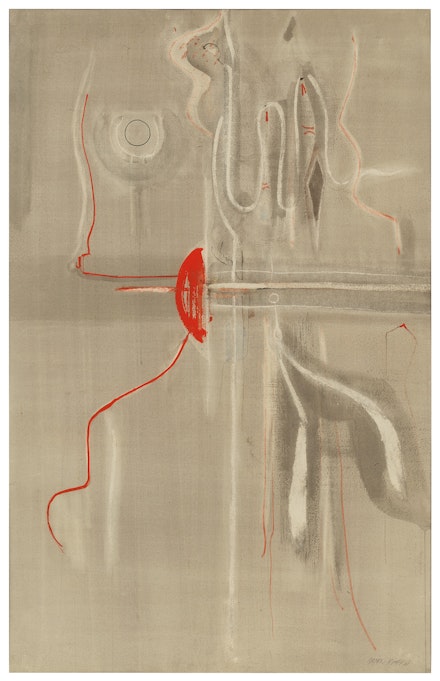

Much has been extolled about Rothko’s retrospective at the Fondation Louis Vuitton (LVF) in Paris, but the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art (NGA), featuring work on two levels, reveals the breadth of Rothko’s painting through highlighting smaller scale works and explorations on paper in which he employs a heavy watercolor paper substrate alternating with watercolor, ink, acrylic, and oil paint. The National Gallery’s lower level is dedicated to the evolution from figures and landscape in watercolor (1930s) to experimentation with monochrome and grayscale Surrealist forms and gestures (1940s) to pivotal work into abstraction, devoid of figuration in 1949. The classic vertically assembled rectangular areas of color became his main compositional structure for the two decades thereafter, until his death in 1970. This exhibition is an exceptional moment to delve into Rothko’s full vision, as the 1950s and ’60s works have largely been held in private collections.

The last lower-level gallery has Rothko’s breakthrough 1950s works in vivid oil and watercolor (sixty are extant). These smaller paintings are mounted on board or wrapped around taking the shape of their rigid support. Color extends beyond the surface to the sides, adding to its physicality and presence as an object. This is enhanced by the absence of protective glass—we are faced with the work itself as it was for Rothko. In his larger paintings on canvas of the same decade (on view at the LVF), we feel the work moving beyond the edges, the drama amplified into our environment, accentuated by the convergence toward an architectural scale by the 1960s. Our body reacts to that which we cannot give words or rationality to, and yet it connects us to one another and ourselves. In the smaller scale of the paintings on paper, Rothko must have found affinity with the fluid wash and spontaneous potential of water-based media, the change in scale a sweet respite from monumental work. We’re peering in, rather than being enveloped by the light emanating from within.

Also in this same gallery, the magic of the inner glow is imminent, like in the violet of Untitled (1959). The play of light and color for certain compositions draws us into the tragedy, elation, loss, laughter, violence, and tangled movement of human emotion reflecting off the surface into our being. How are we transported to the depths of our hearts, our anxieties, in each of these instances? What can pink sandwiched between two opposing grays do to us in Untitled (1959)? Or the turquoise blue rectangle of Untitled (1956), its edges softened with dry brush, revealing the green undertone as it is electrified against the Indian yellow background. Meanwhile, does the floating white rectangle painted above erase or does it overthrow gravity?

At LVF, No. 18 (1951) stood out for its unusually large expanse of white at the base. It lifts the much denser oranges, pinks, and reds upward that vibrate together in musical tones. Isn’t white usually lighter in feeling? The contrast calls upon drama, where the white is holding the weight of the citrus array on its shoulders. Compared with Untitled (1959), at the NGA, the white-lavender rectangular form suspended on top tames the intense blood red crimson and scarlet on its outer edges. The buoyant vibrations motion upward, its softness and cloud-like sensation contribute to silence, and we feel our breath released. Simultaneously, we are weighed down by the darkness of red. In the former, white takes on mass and gravitational pull. In both we are called to contemplation, as if in front of a lake or a basin. The smaller, portable scale of the paintings on paper has the potential of a mirror, where our reflection involves the head more than the full body. Its intimacy is more closely associated with our eyes, our mouth, and our psyche. Whereas with the larger, darker, and monumental paintings from the 1960s, we are set against a stage, traversing it, and bodily engaged. These are deeper and awe-inspiring, where we work harder to discern the nuances of space in low light.

In 1968, Rothko suffered an aortic aneurysm, triggering a shift to working on paper and a scale more manageable for his health. The upper-level galleries at the NGA are dedicated to this intensely productive period of large-scale paintings on paper with acrylic (creating two-hundred-plus works from 1967–69). The penultimate gallery exhibits a selection of Rothko’s “brown and gray” works where the surface is divided into those two colors. These correspond to the same series of work in the last gallery of the LVF. The browns are closer to the radiance of a warm walnut umber bringing us closer to the tactile Earth, while the grayish concoction is more complex, tinted with violets and browns, recalling the milky asceticism of winter. There seems to be hints of fertile hope, but also a naked sadness within the exchange of swirled, agitated brushstrokes and smoothed out washes. What is this single stark division about? Perhaps human drama has crystallized here with more contrast and the tension more polarized, as we try to co-exist between the realms of Apollo and Dionysus.

The last gallery at the NGA offers a different world. Perhaps a seed was born from the brown-gray paintings. Here, the use of white is ever-present, lightening up the whole palette to earthy pastels in gray, blue, mauve, peach, and terracotta, plausibly alluding to the fleshy light and sensual limestone textures of ancient Roman frescoes. Here, Rothko has kept a white border on view as part of the painting (this sharp edge was previously cropped out or painted over prior to 1969). These works embody the fleshiest paintings he has made, both conceptually and physically, as he has allowed the paint a visible thickness for the first time, and some emphasize the portrait format with enhanced verticality.

Tragedy is often not taciturn, or if it is indeed devoid of words, it embodies the violence of silence. It grows through interplays of sound and noise, loud and abrupt, or piercing screams, the body depleted from feeling unnamable things, as much as it is soft, warm, ecstatic, and jumping with elation. Tragedy doesn’t rely on the rational either; it is often full of unexplainable surprises that touch us deeply, make us laugh in absurdity, cry in sadness or stupidity, fight without prevailing, and think how is this possible, where is this going? The seesaw of emotions is ever present in tragic circumstances. Rothko’s work asks us to look outward and then reflect back into ourselves, taking hold of our humanity.