Art In Conversation

Gabriel Orozco with Hearne Pardee

On View

Marian Goodman GalleryMay 12–June 24, 2023

New York

Although he resists the term “nomadic,” Gabriel Orozco has woven an international career through a network of objects, installations, and interventions linked by contingency and contiguity. His use of photography, collage, and found objects has enlarged the scope of sculpture. In 2021 he compressed this complex history into Spacetime, an installation of works drawn from gallery storage. Located downstairs from Marian Goodman’s gallery in Manhattan, Spacetime occupies what was formerly the Francis M. Naumann Gallery. Known for showing Marcel Duchamp and surrealist painters, it’s appropriately ambiguous territory. An informal survey of Orozco’s career, it evokes Duchamp’s Box in a Valise (From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy) (1935–41) and incorporates the three-dimensional compositional strategy of his “working tables.” Orozco envisions his current show at Marian Goodman as an extension of Spacetime, of this “found space” and “readymade gallery.”

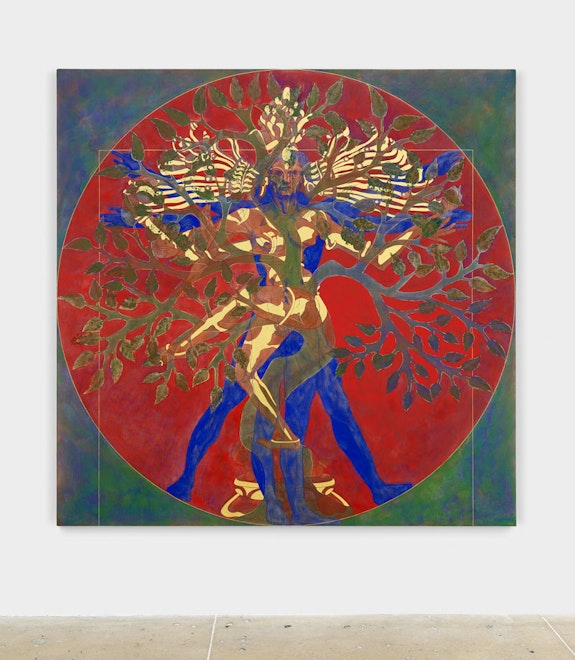

The show includes a working table from Orozco’s studio in Tokyo, along with systematic preparatory studies from Paris, not previously exhibited, for his “Samurai Tree” paintings. Inspired by the knight’s move in chess, the “Samurai Tree” diagram opened the gridded improvisations of his “puddles” into three dimensions to provide a generative armature for subsequent sculptures. In recent years, Orozco has devoted increased attention to painting, culminating in large paintings that interweave Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man with images of trees, frogs, and lotus leaves, emphasizing his long engagement with Asian culture and suggesting a connection between his interest in the pre-Socratic philosopher Parmenides—who intuited the wholeness of the universe—and the Zen Buddhist concept of satori.

Hearne Pardee (Rail): Your new exhibition is very wide-ranging, and also significant because it's probably your last show at Marian Goodman’s 57th Street space—you famously exhibited four yogurt caps in the north gallery there in 1994, one in the center of each wall. I’m curious about how you approached this new show.

Gabriel Orozco: Well, during the pandemic, two years ago when I came into the gallery to sign some works in a space downstairs on the third floor, I had an idea for the Spacetime project, a sort of gallery or viewing room, to include all the work in the storage of the gallery, over thirty-five years of work that Marian Goodman was keeping for me. Some work was mine, some was inventory, some were from various shows, all in different mediums—sculpture, drawings, photographs. So we did this Spacetime project together and it became successful; it was important that the project pay the rent, and it has sustained itself and kept going. So I wanted to make this show a continuation and expansion of that installation. My work being stored in Paris also had to move, from my former assistant Philippe Picoli’s house and workshop which was designed by Le Corbusier for Jacques Lipchitz, and where I worked for many years (2002–2012). So I created another Spacetime from that time capsule of work—preparatory test paintings and drawings for the “Samurai Tree” series that were never shown. And then I created a “Working Table” from my apartment in Tokyo, where I have been working for eight years—things accumulated in shoe boxes from shows I did for Marian and at other museums and galleries. I was motivated to do this Spacetime exhibition because of the found situation. I think of Spacetime like a working table itself, but in a tri-dimensional space—with a ready-made gallery, and the gallery itself works as found object or found space. Yesterday, I had a long interview with Benjamin Buchloh who’s doing a book about the working tables.

Rail: So the exhibition itself is a new work, a “working table” spanning thirty years and three continents.

Orozco: Right, so the work in the show right now—we have four or five spaces spread over two floors—it is a kind of retrospective. The oldest work in this exhibition is a deflated and folded Recaptured Nature from 1990, which is in the Spacetime gallery on the third floor.

Rail: In the upstairs installations, you have your working table from Japan in the center gallery, paintings from Mexico in the north, and the “Samurai Trees” from Paris in the south.

Orozco: Yes. The south gallery has all the works from Paris.

Rail: Which emphasize your process of investigation, including your test versions, in all their variations.

Orozco: Yes. All these boxes with the computer prints, it’s because at the same time that I was doing paintings by hand and exploring techniques to use, I was making all the possible variations on the computer. In 2007 we made a book of all these variations—The Samurai Tree, Invariants. After the first painting was done, I painted a few other variations, but then we printed this book with all 672 possible variations, and not all have become paintings.

Rail: It remains an ongoing process that’s still central in your work. The “Samurai Tree” is a very dynamic, asymmetrical diagram—you base it on the knight’s move in chess—but when you put all the variants in the final grid, it takes on the aspect of your other early “puddles,” where you improvise within gridded fields. They’re like places for germination.

Orozco: Totally right. Yes, the puddles in some of my drawings use a kind of grid that I invented, and then on top I was generating some accidents, stains, or color fields, and I have done that since the early nineties. In my notebooks, you find a lot of these diagrams and drawings. My notebook pages for the “Samurai Tree” are also reproduced in the gallery. But the first time I used them in a painting was in 2004, which was for the show at the Serpentine Gallery in London.

Rail: It was controversial then to make paintings on canvas.

Orozco: But I mixed them with my other work, so I never stopped doing my sculptural work, installation, photography and everything else. Painting just became a part of it, which I still continue doing—I’m constantly using different mediums.

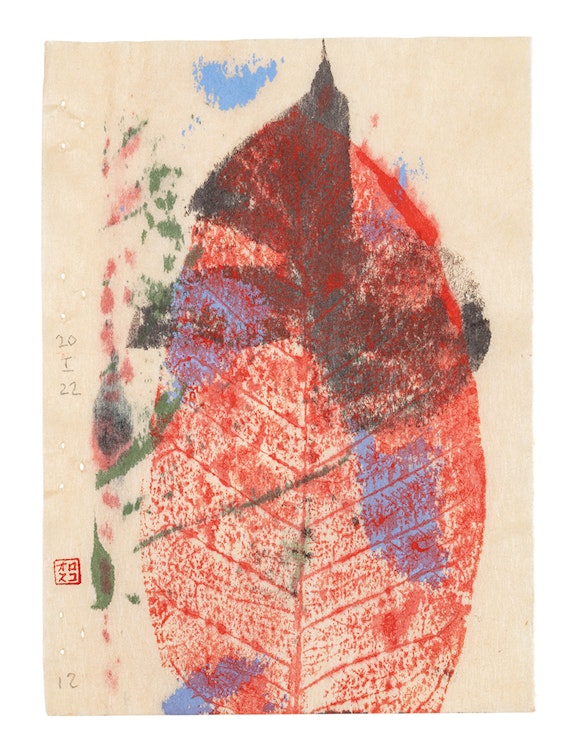

Rail: Over forty “Diario de Plantas” prints are hung around the center gallery and flank the large figural paintings in the front. Those are made in Mexico?

Orozco: Yes, the plant drawings were mostly done in Acapulco, because I have a nice garden at that house. And I was doing some painting there too. I was printing plants and making tests in my notebooks, on Japanese paper, not the regular notebook paper I use. I made several of these and I dated all of them.

Rail: So the “Diario” drawings are all made by hand?

Orozco: Yes, I put paint on the leaves and I press them on the notebook. I close the notebook, so that sometimes they are double prints. And the paper is bound Japanese style: there’s a double page bound with thread. So after I finish the notebook, I unbind the book; I cut the thread and open it. That's why you see the holes.

Rail: Do the drawings combined with the prints come after? Or do you start with a drawing?

Orozco: Normally I start with the drawing.

Rail: The drawings relate to the “Samurai Tree” diagram, but now you also use the Möbius strip.

Orozco: Yes, that's a part of the new research, let's say.

Rail: When did that start?

Orozco: It started with this project, three years ago. So the continuous line of the Möbius strip extends off of the pages. I was doing these plant drawings with ink pens—I have a really lovely collection of good Japanese fountain pens with many different colored inks. And the inks behave differently on this paper, when you add water on top, and then also when you print on top with tempera or gouache. So I was experimenting with plasticity, let's say, with texture, but also with the forms and imprints of the plants. So, the plants became a kind of journal with some impressions taken while I was also painting. Most of my painting work is done in Mexico City, where we use tempera and prepare the colors.

Rail: You’ve said that the large paintings—which culminate in images of the Vitruvian Man and dancing Shiva—emerge from the plant prints, and I’m thinking that’s through connection to your body—recalling prints of your hand like Fear Not (2001), but especially the larger-scale “Corplegados” (2009–2010), one of which is in the third floor space.

Orozco: It's very much related, that's a very good point. The “Corplegados” are on a Japanese paper that is normally used for clothing patterns. They are a kind of map, because I folded them so they could fit in my luggage, in my carry-on. This paper traveled with me and I made some here in New York and some in France. And yeah, I started to put gouache on top and then ink and then imprinted some plants that I found in my garden in Burgundy where I work on ceramics. And the “Corplegados” are kind of my size, the scale of my body. I also cut open two eyes.

Rail: There's also the wall drawing you did called Estela, making a circle with your arms.

Orozco: Yeah, I did that in 2008 or ’09 or so.

Rail: I have it down as 2005.

Orozco: I'm very bad with dates.

Rail: Your references to the body are primarily indexical, going back to the Yielding Stone (1992), that picked things up in a tactile way—more intimately related to the body than an objectified visual representation.

Orozco: Yes, yes. You know the plasticine ball, the Yielding Stone, is my weight in plasticine, right? So when it becomes a mass and starts to rotate, to circulate, it gets all the imprints from the street and the dust that accumulates. So these new paintings are figurative in that you have the body, the Vitruvian Man, but it's not like sketching from nature. In fact, I'm just taking a found, or ready-made drawing, a famous one because it's also very symbolic as a drawing. In a similar way I made La DS, the car, in 1993, the Citroën was a distinctive car charged with some symbolism and history, and then I cut, bisected and reassembled it. I did something similar with the Vitruvian Man when I superimposed a frog overtop. One painting here is even called Vitruvius Frog (2023), and on top of that I imprinted or juxtaposed plants, like the leaf of the Amazonian lotus flower. I also imprinted some leaves in the same way that I was doing in the drawings. So I think that the body has always been present, it's very important, the human body, our scale within the landscape, imprints and our relationship with material.

The car of La DS is also for transporting the body, right? So people feel it in their body when they see the car, when you sit inside, that relationship between body and space and speed, and time and history and memory, because we have memories about the artifacts we use. It's the same thing as when I cut and compressed the elevator to be my own size, and when you went in, you felt like you're going up and down at the same time, because you have the memory of being in an elevator.

Rail: It makes you very aware of how we identify with the containers that we use.

Orozco: And you know, the shoe boxes also. The scale of a shoe box is connected with our body, and the yogurt cups in the first show at Marian Goodman Gallery, they were hung at mouth level, right, so when you arrive in the gallery, the body is shocked to suddenly be in an empty space with four vanishing points, far away. Then you get close to them and you see something that will be very close to your mouth. And you focus on very banal objects that are modifying the perception of the space. I think I’ve done that in different works, in different ways, but always related to the body. Even in the photograph of the bicycle wheel prints on the east side of Manhattan, by the river. So all the works are related to the body. But this is the first time I used found, or ready-made drawings of anatomical figures.

Rail: With relation to ready-made images, what about your “Particle Paintings,” where you turned appropriated paintings into pixelated grids.

Orozco: I was making the particle paintings from photographs or other paintings. I did one with a Pollock painting. I did one with a Monet painting, and I did one of a Ho Chi Minh portrait.

Rail: So reproducing the Vitruvian Man extends the idea of taking paintings and using them for something else.

Orozco: Yes, yes, found objects, recycling things you find—the beetles are also from my books on animals and plants. But then the “Atomists” (1996), for example, are sports photographs found in newspapers, with superimposed diagrams in colors, the same as blowing up the pixels or the dots that used to be printed before pixels.

Rail: You’ve mentioned that in Japan, you got involved with looking at Matisse, a great figure painter, very interested in Japanese art. In an interview, you speak of artists who look at things, and Matisse is always working from a model in his studio. Matisse also went through a big change when he moved to Nice in the middle of his life. There he got very involved with the culture of North Africa, the screens and the textiles and objects he would use.

Orozco: With everything, because he was collecting all these objects: his chairs, his jars, the flowers—he always has flowers—and the plants on the window and the light. In every work, every little drawing, Matisse is looking at something. That's why they are so sensitive, because he's not drawing from memory. Picasso did more schematic or expressionistic drawing, because he was thinking, he was not always working with the model, right. So I think Matisse is very much a voyeur. And of course, there are many things that for us seem to be a little strange now in his voyeuristic approach to the world.

Rail: Let’s think about his Red Studio from 1911. Like you in your working tables, Matisse put in art works, decorative objects, tools, the total space of that red monochrome.

Orozco: Yes. You're totally right. And I remember discussing that red painting with Ann Temkin, who curated the exhibition at MoMA, and also curated my show at MoMA. And I remember talking with her about that painting because it's a very important painting for me precisely for that reason, because it is many works within the work. So you have the reproduction of his paintings in this big painting, and the space is kind of empty because he just filled it with red, but then you have all the works there. So it's a little bit of a spacetime.

Rail: But more than looking at Matisse, you’ve gone directly to Japan, and before that to India. So we should talk about your iconography—a word not normally used in discussing your work—because you superimpose the Shiva figure, and other things like plants, over the Vitruvian Man.

Orozco: Well, Shiva is also a very symbolic shape from a totally different culture, and is also usually within a circle, and it describes many different things like movement, life, and time. Images of Shiva dancing can often have many different arms. It is male, female, goddess, rationality… I thought it was interesting—the symbolic organicity of the Shiva versus the technical human proportions of the scientific Vitruvian Man. The Renaissance rationality versus what we could say is the yoga playfulness of seeing the cosmos and nature in Indian culture. And the symbolic weight they give to the tree of life and the pond with its lotus plants and frogs as the center of the universe.

Rail: Did you encounter Shiva in Bali? With the stone carvers there?

Orozco: Yeah, but much before Bali, I was traveling to India.

Rail: Right, you got your idea for your house there.

Orozco: The Observatory House (2006) is also a mandala, a square with a central circle. It's an observatory building based on the proportions of the Jantar Mantar Observatory in New Delhi (1724). When I was a kid, my father had a very nice book about Indian sculpture, especially the Khajuraho reliefs that are also very erotic and very, very beautiful. So since I was a kid I was looking at Indian sculpture. I still refer to it often. You know, I have this sculpture I bought in India —I’ll bring it here… This is from India. It's the Soul of the Liberated Man.

Rail: It’s an empty silhouette of a figure, made of metal.

Orozco: It's a Jain figure. And you know, when you attain enlightenment it’s because you emptied yourself. You're completely empty. You become a void. So then you can perceive the universe, you can be part of the heavens and universe.

Rail: Speaking of emptiness, I'm interested in the installation in the south gallery, where you left so much empty space on that big table in the center of the room—you just put one of your small samurai prototypes in the middle. It’s like the inverse of the very full working table in the next gallery. What was your thinking?

Orozco: Well, we were building the spaces to receive the different works, the different sizes, and weren't sure how they would work together in the final installation. It’s kind of messy, because some of the works are damaged, some of the works are unfinished, like in a working table. In the end, I didn't like how it looked with too much stuff. So in storage I had this prototype 3D print of the Samurai Tree. And I put it right in the center of the square. My paintings are always square, but I also think very much in mandalas, in shapes that rotate, so it's not a horizontal landscape or a vertical figure. It's a square that works in a rotational way as a diagram.

Rail: The empty space and all the documentation in that room really underline the importance of the “Samurai Tree” in your overall work. It embodies sculpture for you.

Orozco: Exactly right. And also it's a square.

Rail: What about the little clear cube on the corner of the table?

Orozco: The clear cube is a test I made, placing the drawing inside a glass cube.

Rail: Purely space.

Orozco: Right. I did it in Paris and I found it maybe too beautiful. And I didn't do anything with it. But now I might try to do it in a larger format. And then on the other corner is the model in mylar for a large piece called Blind Signs (2013), which is a transparent labyrinth—a walled glass maze with circular black stickers, like the material you would use to make a transparent surface visible; what you would put on glass windows to protect birds from flying into them, or in buildings to protect the public from walking into glass doors or windows.

Rail: But moving on to the very full working table in the next room, let’s talk more about the influence of Japan, where you’ve lived part-time since 2015. You’re obviously very involved with Japanese traditional crafts and the whole culture. What was it like to move there?

Orozco: Well it's like what was first: the chicken or the egg? I was interested in Japanese, Indian and Asian art and culture since long ago even before visiting Japan. So I went to visit a few times, then also to India—I traveled there with Maria, my wife, many times—but I think it was more through books and thinking that I was interested. I was reading a lot of Suzuki, about Zen Buddhism. And I really like the way he’s also a philosophical thinker. That influenced a lot of my work, even the shoe box, you know, the emptiness of the shoe box, or the fluctuation of the Yielding Stone. The “Samurai Tree” is a kind of mandala or a diagram of movement, and the flatness of it—a tri-dimensional proposition related to chess—also relates to the tradition of Japanese painting that is quite flat. It’s their different sense of perspective, not trying to reproduce volumes tri-dimensionally as in the Western tradition. So thinking of art and images in Japan, India, China, and Korea has always been important to me. But I also think that Mexico has this kind of culture that is not completely Western—the imagery in Mexican painting is very connected with shapes and geometry.

Rail: You know Roland Barthes’s book on Japan, Empire of Signs. He talks a lot about packaging, which relates to much in your work, especially the “Roto Shaku” sculptures, which are essentially wrapped pieces of wood. Also about haiku, which I think of in relation to the plant prints in your journal. Haiku resists interpretation—Barthes calls it an incident.

Orozco: Yes, and also in the teachings of Buddhism. There is this word I like, satori, when you cannot explain something, and you have to make a gesture that is abrupt, almost violent, to respond. There are also many anecdotes from Borges, who writes about this authority, and sometimes in my work I try to generate this. To go back to La DS, it was very hard to make, to cut very carefully and assemble again, but when you see it, you have the feeling of immediacy, you feel it as if it just happened, just like voom! This is a kind of satori application, in the car. And then the haiku is nice. I mean, some people say that my work is very poetic, and I will say that it's by accident, because you cannot intend to make poetry in art, especially in visual art. I think the poetic is something that happens by accident, without your being in control of that possibility. The poetic in everyday life, in photography or even in writing, is a little bit like provoking accidents. When suddenly you make sense of an accumulation of words in a very unconventional way that end up being metaphoric and then poetic. But the same thing happens with painting, I think, in an abstract painting especially. I don't know if someone will say the “Samurai Tree” is poetic, but it definitely is. It's abstract in a different way than Mondrian. I think Mondrian, it's still very much the window and the landscape and the grid, but the “Samurai Tree” is also like a diagram or a board game, like the structure of a tree, of a geometric organism.

Rail: While we're talking about Japan, could you say more about the “Roto Shakus” and “Obi Scrolls,” which appear as works in progress on the working table?

Orozco: Yes. In the table we have these tests I was doing with the “Roto Shaku.” These are standard pieces of wood—the Japanese have their own scales and standards for different materials so that rooms are regularly proportioned. And Japanese traditional architecture influenced a lot of modern architecture using models and standard measurements. So the “Roto Shakus” reflect that, combining the wrapping tradition and architectural proportions.

Rail: Like your carvings from Bali, they’re deeply sculptural, using a readymade structure but giving each one its own character as you wrap colors around the stick.

Orozco: That's right, and then the scrolls, which are usually ink on paper, pasted on fabric and then rolled up for transportation and preservation. They are meant to be unrolled only to view—they are not normally shown for twenty-four hours all the time—so you can change them depending on who is your guest, the season of the year and all that. But I made an inversion, using old fabrics and belts from kimonos. I cut them and inverted them like some of my collages, cutting out circles and then rotating the images.

Rail: Did you actually reweave those?

Orozco: No, I was more into the cutting, and then I went to a conservator, because that’s how they do it, they paste the paper with glue—rabbit skin glue I think—they paste the paper with the calligraphy, onto the fabrics. But I just did it the opposite way. I treated the fabric as if it was the calligraphy, so the cutting of the circles and the rearrangement of the weave and pattern of the fabrics is a little bit like a calligraphic gesture.

Rail: Do you practice calligraphy?

Orozco: No, I do my own calligraphy in my notebooks, but traditional calligraphy, no. But I was trained as a painter so I know how to use the brushes, let's say. My brushes are more eastern style. The brushes that Matisse used, for example, are more flat, more western style, for oil.

Rail: So do you use them on your big paintings?

Orozco: Yes, I like the calligraphy style brushes, even in my paintings. I think the Möbius strip in gold leaf on some of the paintings have a calligraphic continuity of line.

Rail: There's perhaps less spontaneity to the Möbius line because it’s very regular, different from the more incidental way that calligraphers work.

Orozco: Oh yes, totally. But I was thinking more in the “Samurai Tree” geometry and then I was trying to reproduce that in the Möbius strip. So the geometry is not loose, but those superimpositions on the paintings are very, very organic.

Rail: Relating to that, I wanted to ask about a painting from your show last fall in London, which included some larger paintings of plants and animals. I was interested in the large painting of a pineapple, in which the Samurai diagram generates a pattern of organic growth that actually constructs a plant, a little like using Legos. I don't see that so much in your big paintings here.

Orozco: Yeah, well, I did it maybe in the Amazonian lotus leaf combined with Vitruvius, because the intertwining veins of the leaves are there. But you're right—the pineapple came from a very old drawing by a Portuguese monk and explorer, who was drawing the animals and plants in Brazil, and I found that pineapple to be a beautiful drawing. Then I took the geometry of it—I did it with a compass, and we organized it more geometrically and it became a very nice pattern, almost like a fractal.

Rail: It grew out of smaller units.

Orozco: Exactly. So that painting is nice. And for that series of paintings I wasn't using the human figure but animals like crabs and lobsters.

Rail: In the painting you just mentioned, Vitruvius amazonica (2023), you weave the layered images together—you extend the process of layering from the leaf prints to create hybrid creatures. That seems like something new. You merge the human into the larger organic world.

Orozco: I have always been interested in the scale of the human body in relation with the larger organic world. As much as in the microcosm of nature as in the macrocosm of urban landscapes and vice versa.

Rail: Is there anything you want to discuss that I haven't asked about?

Orozco: I like your questions a lot, covering a lot of works from many different years.

Rail: Thank you—I tried to surprise you with things but you're very agile.

Orozco: Well, one thing that perhaps is not so known in detail is the work I'm doing with the national park in Mexico, in Chapultepec Park. I was in charge of the master plan for the whole project, but I work with different teams, biologists and environmental experts but also with different architects for different projects. And we did three competitions for specific museums, pavilions. And then I designed the bridge that will connect the first and second sections through the Periférico [beltway]. It ended up being quite different than a regular bridge.

Rail: You envision some of your installations as parks, like Clinton is Innocent (1998) in Paris.

Orozco: Totally, it’s like a landscape or a promenade. Many installations I do are trying to generate a landscape in the exhibition. I have made Moon Trees (1996) and Ventilators (1997)—fans with toilet paper that became like flying birds. And then the four-way ping pong table with the pond in the center is like a fountain(1998). That was in the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, which curves. The relationship with architecture or public spaces has always been interesting to me, although I don't often do commissions. There is really just the whale in the Library Vasconcelos in Mexico from 2006. And then I was asked to design the garden at the South London Gallery in 2016. And then with the Chapultepec project—it is so big that of course, I never even thought about me designing everything.

Rail: That's amazing.

Orozco: But I love to see the book on Central Park, with all the designs of the bridges that look kind of similar, and this is very nice, but in Chapultepec you have so many layers of different moments in architecture and history. You have a castle that used to be a military compound that now is recovered as a park. So that big project is still going on. I should finish it next year.

Rail: I'll have to go back to Mexico City then.

Orozco: Well, I have a show next February. So maybe it's a good time to come?

Rail: That’s possible.

Orozco: But yeah, the drawings of this bridge, and the way it came out, is very much like a sculpture I think. And I refer to it as a sculpture, because it is a functional sculpture that you can use, but the sequence and structure of the legs, and the circles stamped in the concrete on the pathway, the winding through the trees, makes it very much like a Möbius strip on the bridge.

So that would be a nice ending.

Rail: The Möbius strip going on and on.

Orozco: Yes, that's right.